10 Greatest Wrecks

Skuldelev Ships

By JAMES P. DELGADO

Monday, March 11, 2013

Starting in 1962 and continuing with more recent recoveries, a group of eleventh-century Viking ships have been lifted out of the shallow waters off Roskilde, a former capital of Denmark. The ships, ranging from common cargo carriers to warships, had been filled with stone and sunk to block a sea channel from invaders. The finds, and the analysis and reconstruction of the ships led by the late Ole Crumlin-Pedersen, provided the world with its first detailed look at a range of Viking craft separate from the more ornate royal craft discovered in ship burials on land. The Skuldelev ships speak to sophisticated shipbuilding as well as extensive specialization. Their discovery has helped to overturn the commonly held stereotype of a “Viking ship” as a large dragon-beaked warship lined with shields. The work on the Skuldelev ships has included the creation of sailing replicas and helped drive resurgent interest in the Vikings as diverse and skilled traders, explorers, and warriors with a command of the seas. Starting with Skuldelev and continuing with finds in former Viking ports such as Dublin, Ireland, archaeology has rewritten Viking maritime history.

Khubilai Khan Fleet

By JAMES P. DELGADO

Monday, March 11, 2013

The largest naval invasions in history were the seaborne assaults of 1274 and 1281 on Japan by Mongol, Chinese, and Korean soldiers, marines, and sailors under orders from Emperor Khubilai Khan. According to legend, the ships numbered in the thousands and more than 100,000 men participated in the 1281 attack. Both invasions were part of the Khan’s plan to assimilate Japan into the Mongol Empire—and both failed. Japanese legend and an account by Marco Polo blame the defeat on a heavenly sent wind, or storm, in response to prayers for deliverance. The legend of that wind, the “kamikaze,” would later inspire Japanese World War II pilots to fly their planes into Allied ships. Since the 1980s, and especially in recent years, archaeological surveys and excavations led by Torao Mozai and Kenzo Hayashida have yielded a large number of artifacts, including weapons, armor, containers for provisions, personal items, and the fragmented remains of some of the ships. Analysis by Randall Sasaki and Jun Kimura of the Chinese-built warships has revealed that they were far more advanced in their construction and technology than contemporary European craft. And excavations have yielded the oldest sea-going bombs, catapult-launched ceramic shells packed with gunpowder and metal shrapnel. In addition, archaeological research has been able to augment limited documentary evidence of the details of the Japanese defense and victory. Finds offer clear evidence of the use of fire ships—craft set ablaze and launched at the enemy—and of hand-to-hand combat on decks. These efforts held the invaders off the beaches until a seasonal typhoon wreaked havoc. Further, excavations show that the attacking ships were rushed into war and appear to have been in poor condition, some from the ravages of battle and some from having been built in haste. Inadequate preparations on the part of the attackers, compounded by what became a protracted siege against an indomitable foe, spelled defeat when time ran out and the weather turned. These archaeological discoveries not only bring a legend to life, but also have helped to greatly increase our knowledge of naval warfare in Asia.

Bajo de la Campana

By JAMES P. DELGADO

Monday, March 11, 2013

The first Phoenician shipwreck to be excavated by archaeologists, the wreck at Bajo de la Campana, a submerged rock reef off Spain’s coast near Cartagena, dates to some 2,700 years ago. The ship ran aground and spilled its cargo onto the seabed, where a number of finds ended up clustered in a sea cave. Under the direction of Mark Polzer and Juan Piñedo Reyes, archaeologists recovered fragments of the hull along with a large number of ceramic and bronze artifacts, as well as pine nuts, amber, elephant tusks, and lead ore. The tusks include examples engraved with the Punic names of their owners. The Bajo de la Campana ship was likely a trader from the Eastern Mediterranean that journeyed west, at least as far as today’s Cadiz, in its quest for goods. Most were raw commodities, such as the ivory and lead ore, which the ship’s crew had acquired through trade with the indigenous people of this part of Spain. The wreck at Bajo de la Campana is still undergoing analysis by Polzer and Piñedo at Cartagena’s Museum of Underwater Archaeology but has already yielded evidence of a wide maritime trade network. The Bajo de la Campana ship demonstrates, like the earlier Cape Gelidonya and Uluburun ships, that commerce by sea linked cultures and helped build trading empires—in this case, that of the Phoenicians. In time, they dominated the Western Mediterranean, established port cities and colonies such as Cartago Nuovo (today’s Cartagena), and ultimately clashed with the growing power of Rome.

Kyrenia

By JAMES P. DELGADO

Monday, March 11, 2013

The excavation and recovery of the well-preserved remains of this late-fourth-century B.C. Greek merchant vessel off the coast of Cyprus has yielded substantial information on the construction of classical Greek boats, often seen depicted in paintings on ancient ceramics. The archaeology, led by the late Michael Katzev and now being completed by Susan Katzev, showed that sometime around 306 B.C., the ship, with a four-person crew from Rhodes, was overcome and sank in what seems to have been a pirate attack that left eight iron spear points embedded in the hull. This nearly two-thousand-year-old victim is the earliest physical evidence of piracy. After conservation and reassembly, the hull of the Kyrenia ship is now on display in the Kyrenia Crusader Castle on Cyprus. Also, a sailing replica of the ship, launched in 1985 and christened Kyrenia II, was a successful application of experimental archaeology. It has allowed archaeologists to learn much more about the form and handling abilities of these now-vanished ships.

Cape Gelidonya and Uluburun

By JAMES P. DELGADO

Monday, March 11, 2013

The two oldest wrecks ever excavated, these two Bronze Age ships and their cargoes, were discovered off the coast of Turkey. Excavated in 1960 (the site was resurveyed and small additional finds uncovered in 2010), Cape Gelidonya was the first ancient shipwreck to be dug in its entirety from the seabed by archaeologists. Dating to around 1200 B.C., the vessel was most likely the possession of an itinerant metalsmith of Cypriot or Syrian origin, and the wreckage has yielded more than a ton of ingots, scrap bronze tools, weapons, and other objects, as well as metal-working tools. The artifacts convinced original excavator George Bass—known as the father of underwater archaeology—that ancient Mediterranean maritime trade had not been dominated by Mycenaean Greeks. Finds of Greek artifacts at a number of land sites had fostered that view, but Bass believed instead that Near Eastern seafarers, or “proto-Phoenicians,” were more likely to have controlled those ancient trades and seas. This hypothesis was borne out by the discovery and 1984–94 excavation of the Uluburun wreck, which dates to around 1330 B.C. Either Canaanite or Cypriot, the Uluburun ship carried a diverse cargo of raw and manufactured luxury items and commodities from at least 11 far-spread ancient cultures, ranging from the Baltic to Equatorial Africa, the Mediterranean world, and the Near East. The meticulous recovery also produced fragments from this oldest wreck’s hull. Ongoing analysis by excavator Cemal Pulak now proves Bass’ hypothesis and demonstrates a complex, sophisticated maritime trade network dominated by the proto-Phoenicians more than three millennia ago. Thanks to these two ships, we now know that the ancients were savvy seafarers who built what was for them a “global economy.” The Cape Gelidonya excavation led to the founding of both the world-class Bodrum Museum of Underwater Archaeology in Turkey and the Institute of Nautical Archaeology, the world’s leading scientific organization dedicated to the excavation and study of significant shipwrecks.

The two oldest wrecks ever excavated, these two Bronze Age ships and their cargoes, were discovered off the coast of Turkey. Excavated in 1960 (the site was resurveyed and small additional finds uncovered in 2010), Cape Gelidonya was the first ancient shipwreck to be dug in its entirety from the seabed by archaeologists. Dating to around 1200 B.C., the vessel was most likely the possession of an itinerant metalsmith of Cypriot or Syrian origin, and the wreckage has yielded more than a ton of ingots, scrap bronze tools, weapons, and other objects, as well as metal-working tools. The artifacts convinced original excavator George Bass—known as the father of underwater archaeology—that ancient Mediterranean maritime trade had not been dominated by Mycenaean Greeks. Finds of Greek artifacts at a number of land sites had fostered that view, but Bass believed instead that Near Eastern seafarers, or “proto-Phoenicians,” were more likely to have controlled those ancient trades and seas. This hypothesis was borne out by the discovery and 1984–94 excavation of the Uluburun wreck, which dates to around 1330 B.C. Either Canaanite or Cypriot, the Uluburun ship carried a diverse cargo of raw and manufactured luxury items and commodities from at least 11 far-spread ancient cultures, ranging from the Baltic to Equatorial Africa, the Mediterranean world, and the Near East. The meticulous recovery also produced fragments from this oldest wreck’s hull. Ongoing analysis by excavator Cemal Pulak now proves Bass’ hypothesis and demonstrates a complex, sophisticated maritime trade network dominated by the proto-Phoenicians more than three millennia ago. Thanks to these two ships, we now know that the ancients were savvy seafarers who built what was for them a “global economy.” The Cape Gelidonya excavation led to the founding of both the world-class Bodrum Museum of Underwater Archaeology in Turkey and the Institute of Nautical Archaeology, the world’s leading scientific organization dedicated to the excavation and study of significant shipwrecks.

Advertisement

Page 2 of 2

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

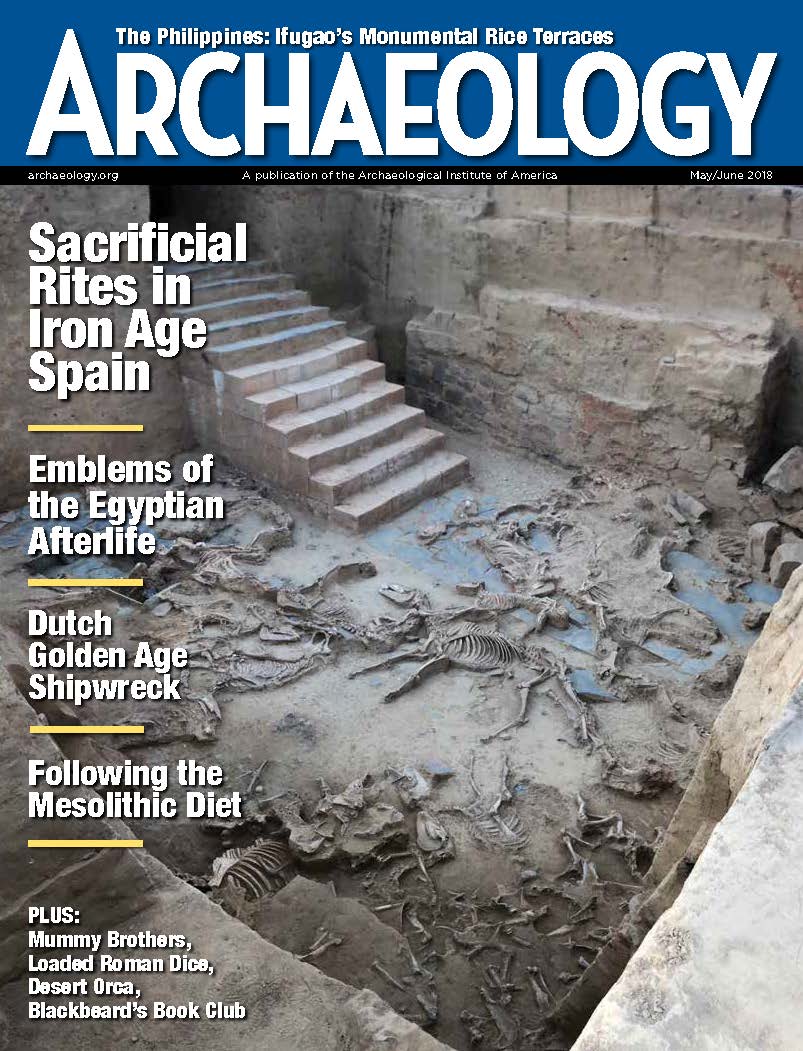

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

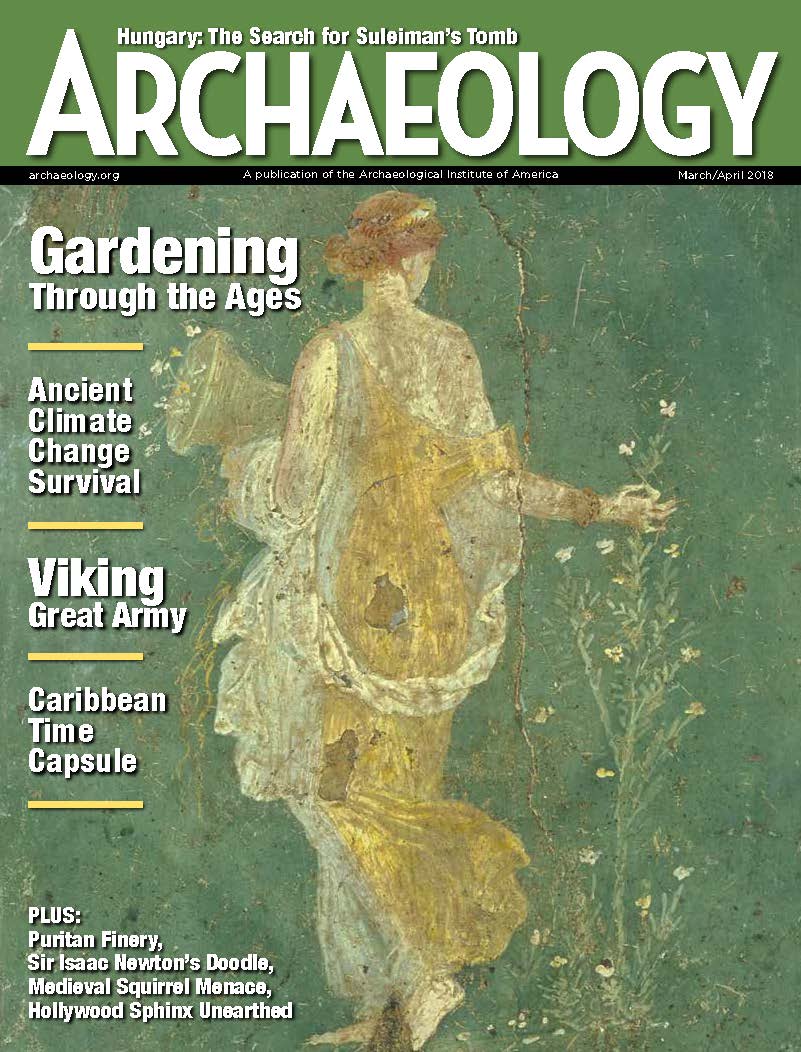

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

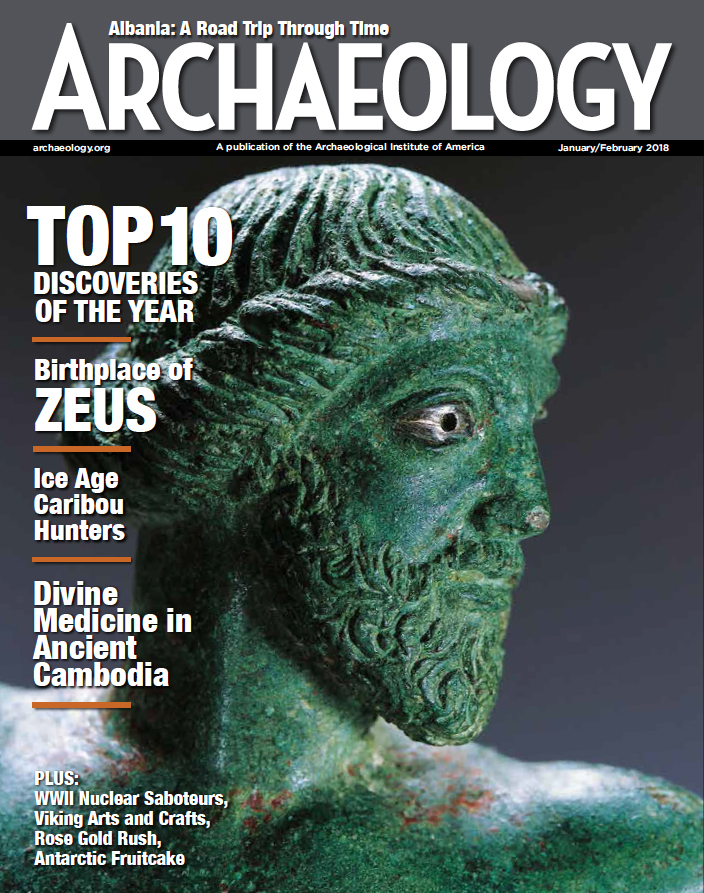

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

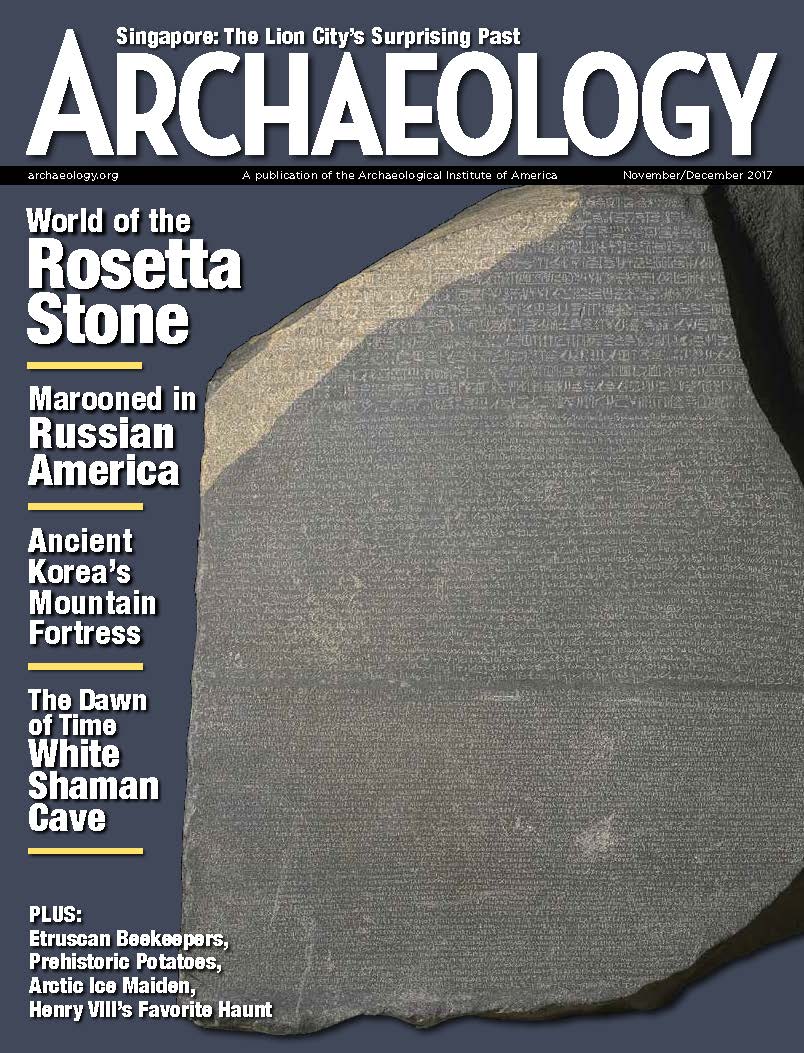

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

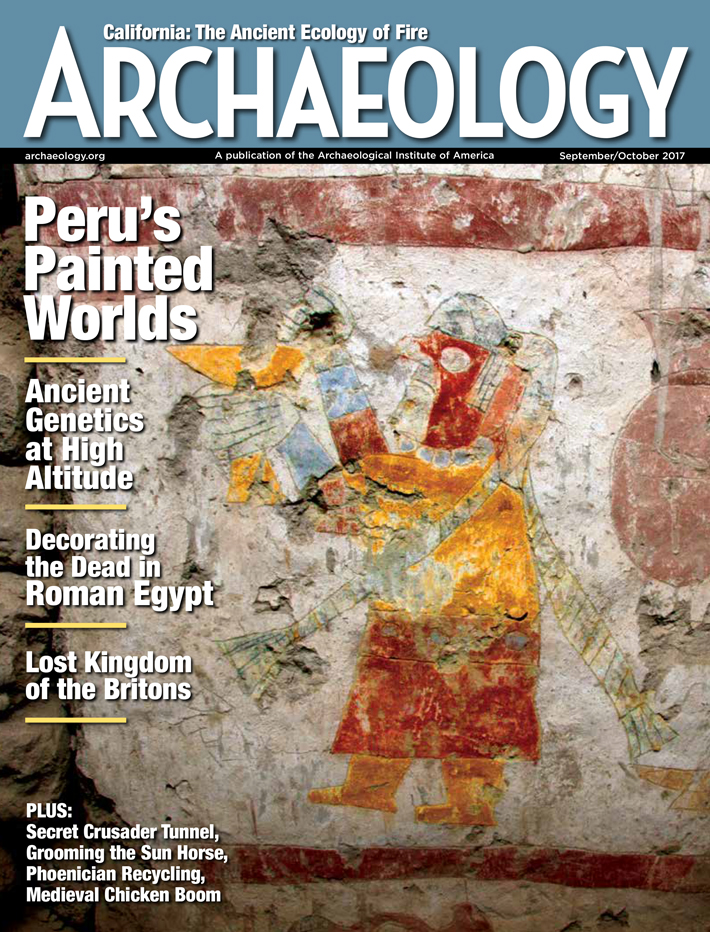

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

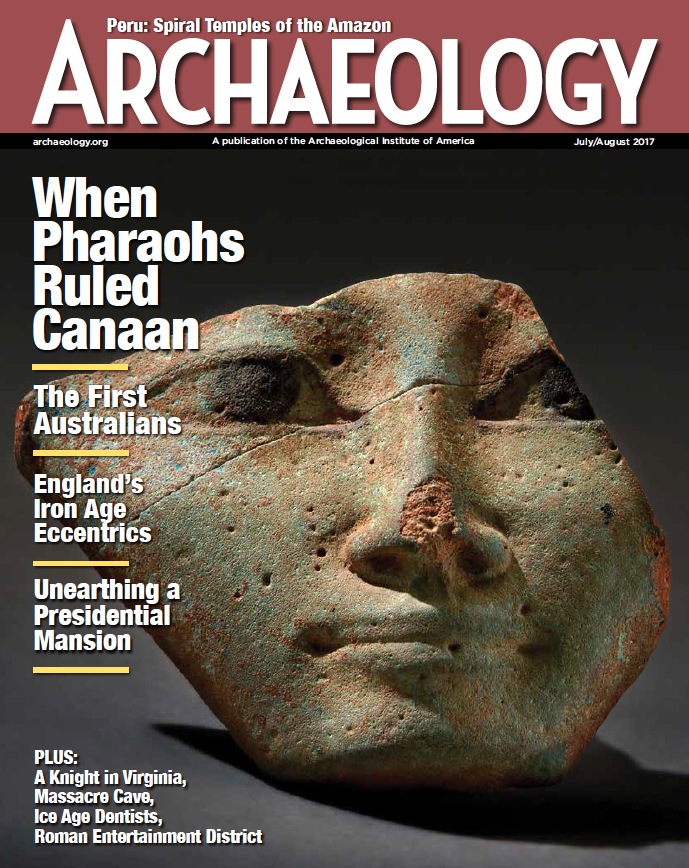

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

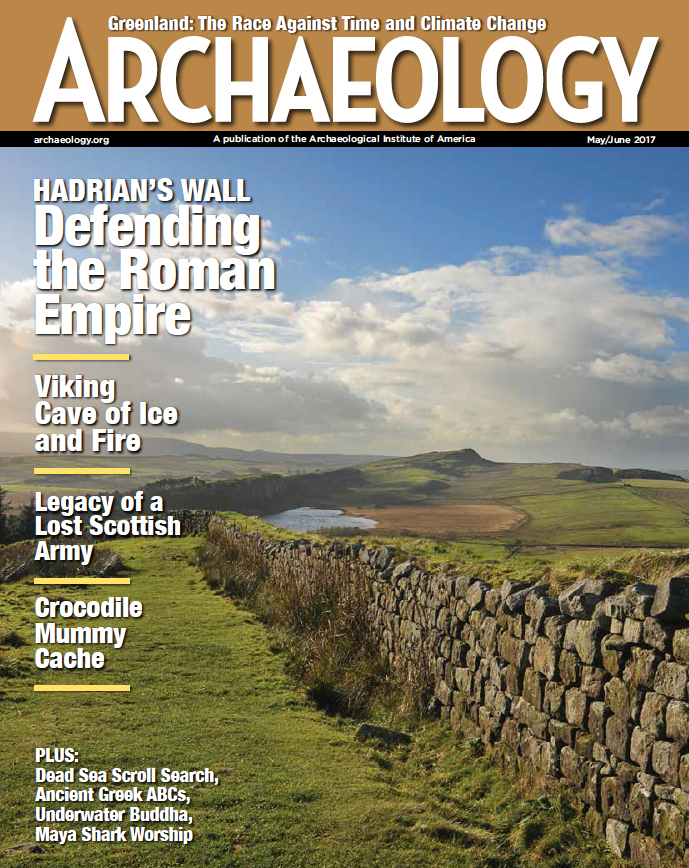

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

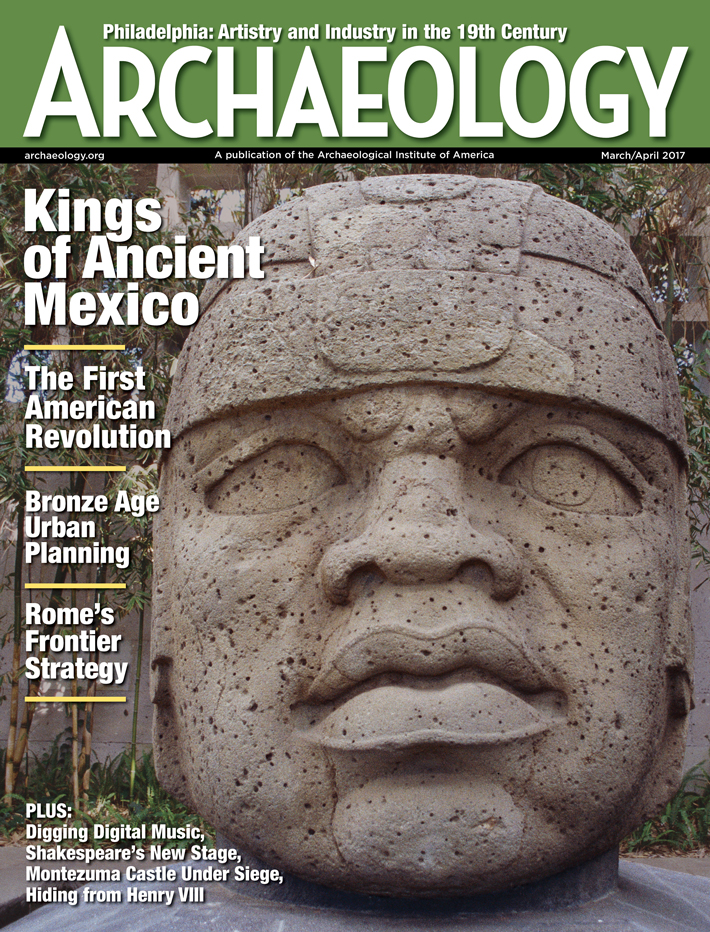

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

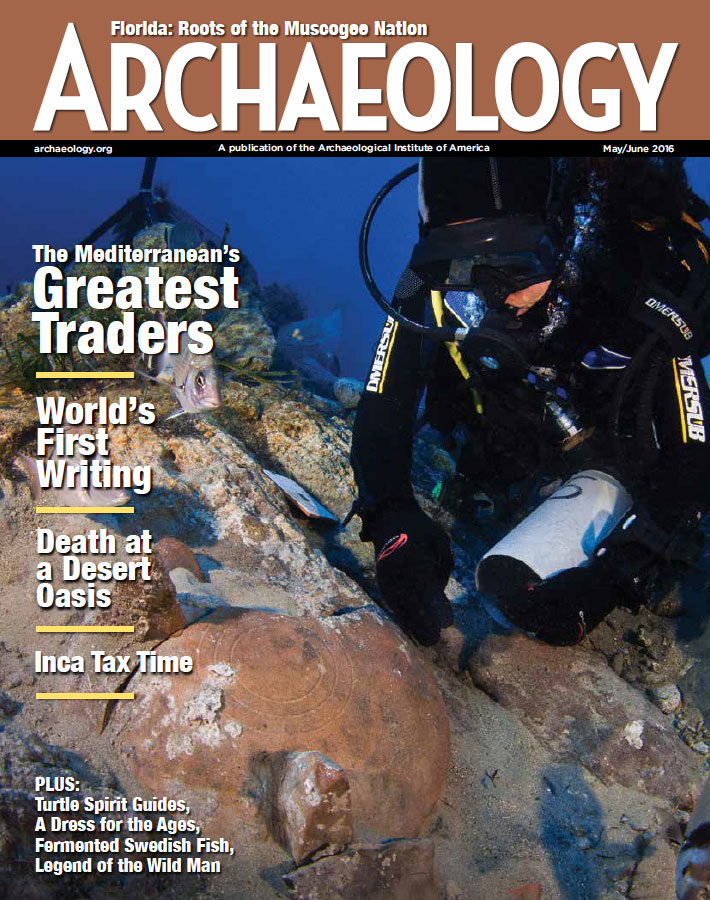

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

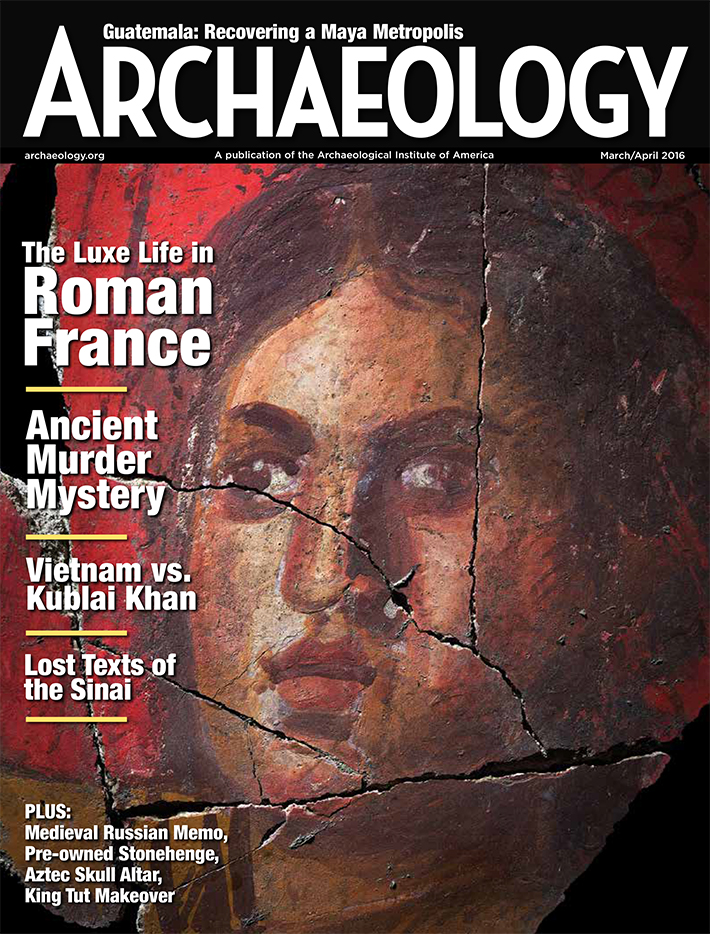

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

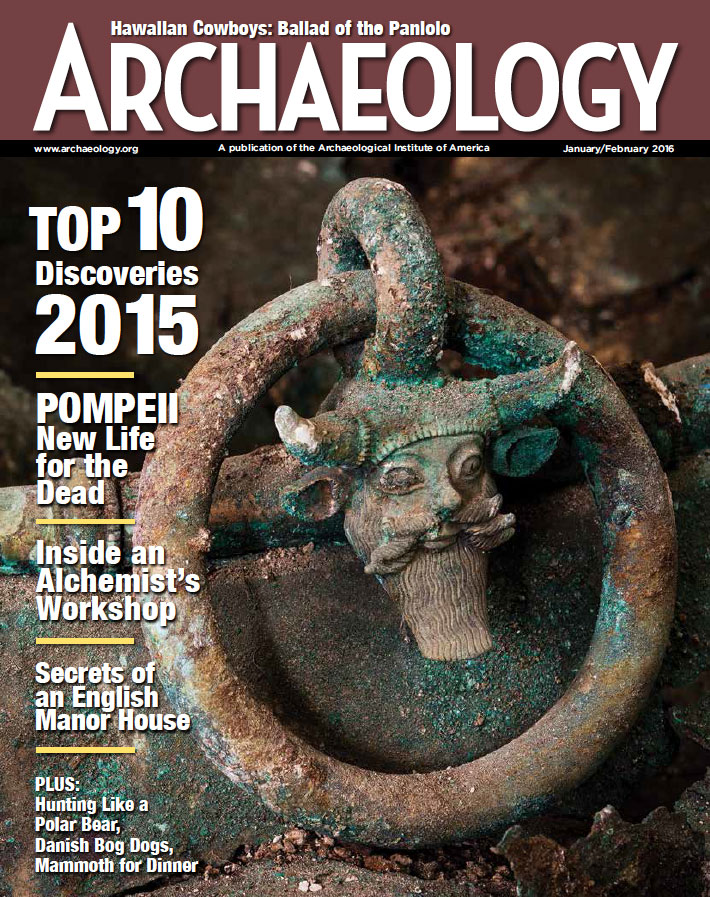

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

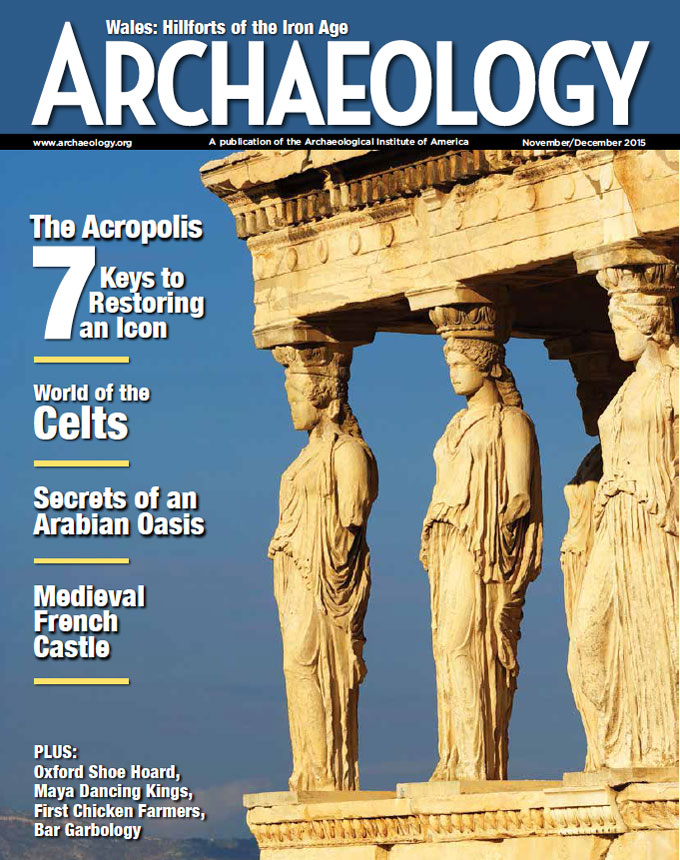

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

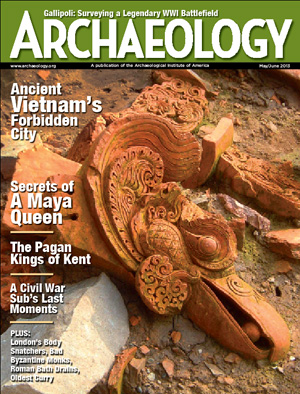

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

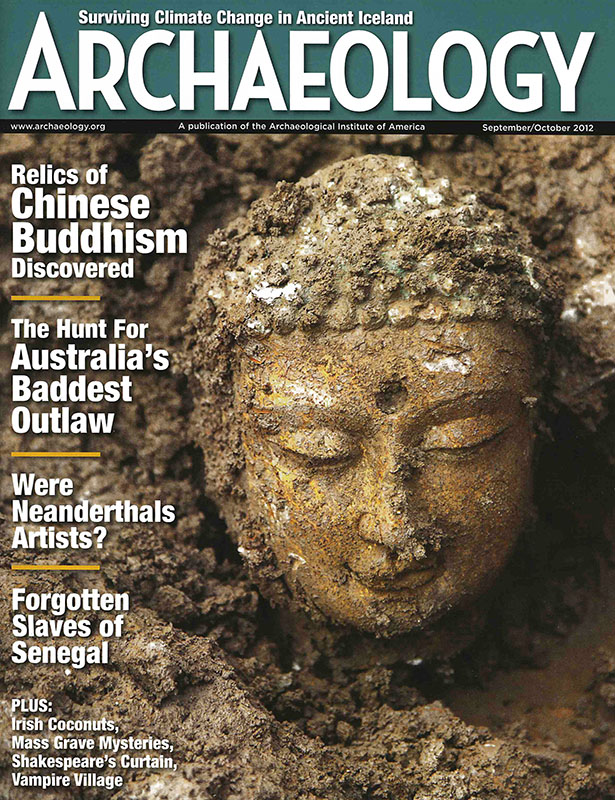

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

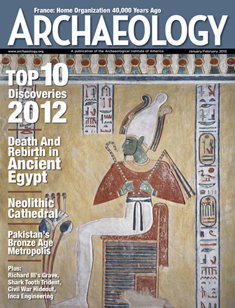

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement