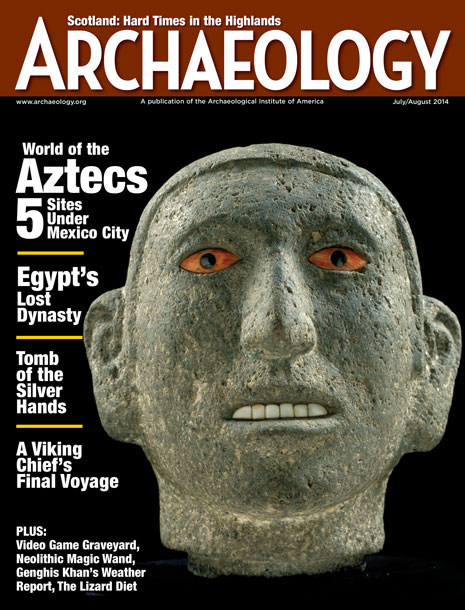

Templo Mayor

July/August 2014

When the Spaniards arrived in Tenochtitlan in 1519, the Aztec capital’s main shrine stood 150 feet high. Little still stands of that building today because the Spaniards demolished it and used its blocks to build their own cathedral, known as the Metropolitan Cathedral of the Assumption of Mary, within sight of the remains of the once soaring temple. Possibly unknown to the Spaniards, however, at least six earlier versions of the Templo Mayor still lay underneath the structure they destroyed, the result of each successive ruler building his own temple on top of the previous one.

When the Spaniards arrived in Tenochtitlan in 1519, the Aztec capital’s main shrine stood 150 feet high. Little still stands of that building today because the Spaniards demolished it and used its blocks to build their own cathedral, known as the Metropolitan Cathedral of the Assumption of Mary, within sight of the remains of the once soaring temple. Possibly unknown to the Spaniards, however, at least six earlier versions of the Templo Mayor still lay underneath the structure they destroyed, the result of each successive ruler building his own temple on top of the previous one.

Since the early 1980s, archaeologists have been delving into those earlier layers, gaining a look at how the Aztecs worshipped decades before the conquest. Because these remains had been buried since the 1400s, they are giving researchers an unprecedented look at classical Aztec society. One of the first artifacts they excavated was a monumental stone disk dating from an early phase of the temple’s construction, around 1400, depicting the moon goddess Coyolxauhqui, a figure from the Aztec creation myth. In the legend, the goddess was decapitated and dismembered at the hands of her brother Huitzilopochtli as punishment for disrespecting their pregnant mother. Archaeologists have concluded from the chopped-off human limbs and heads excavated near the temple’s base that the grisly scene was reenacted regularly at Huitzilopochtli’s altar on the summit. Rows of skulls made of stone and stucco, still visible today, had their counterparts in actual skulls excavated nearby.

The carnal nature of Aztec worship has long intrigued researchers, in part because its focus on blood-drenched sacrifice in the public square had few parallels in other Mesoamerican societies. Scholars suggest that the elites may have felt insecure in their power, and responded with these grandiose, intimidating rituals. “You get a sense of who ran society and how they made themselves loom large over it, monumentalizing themselves, and how they expressed power with these acts,” says Harvard University historian David Carrasco. Sacrifice was also closely linked to warfare—the victims were mostly battlefield captives—and thus to economic domination over neighboring states, explains archaeologist Eduardo Matos Moctezuma.

The carnal nature of Aztec worship has long intrigued researchers, in part because its focus on blood-drenched sacrifice in the public square had few parallels in other Mesoamerican societies. Scholars suggest that the elites may have felt insecure in their power, and responded with these grandiose, intimidating rituals. “You get a sense of who ran society and how they made themselves loom large over it, monumentalizing themselves, and how they expressed power with these acts,” says Harvard University historian David Carrasco. Sacrifice was also closely linked to warfare—the victims were mostly battlefield captives—and thus to economic domination over neighboring states, explains archaeologist Eduardo Matos Moctezuma.

The greatest Aztec conqueror of them all, Ahuítzotl, was cremated upon his death in 1502 and his ashes placed in an urn at the base of the temple, according to sixteenth-century accounts. Archaeologists thought they might be close to finding his remains in 2006 when they excavated a stone inscribed with the year 10 Rabbit in the Aztec system (which corresponds to A.D. 1502) along with artifacts suggesting an elite burial. They now think that the urn with Ahuítzotl’s ashes had actually been dug up in 1900 by Mexican archaeologist Leopoldo Batres, who did not know he’d struck the Templo Mayor. At that time, the neighborhood around the buried ruins had few houses and a reputation for bad omens and ill spirits, likely a remnant of the site’s bloody history, says archaeologist Raúl Barrera.

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

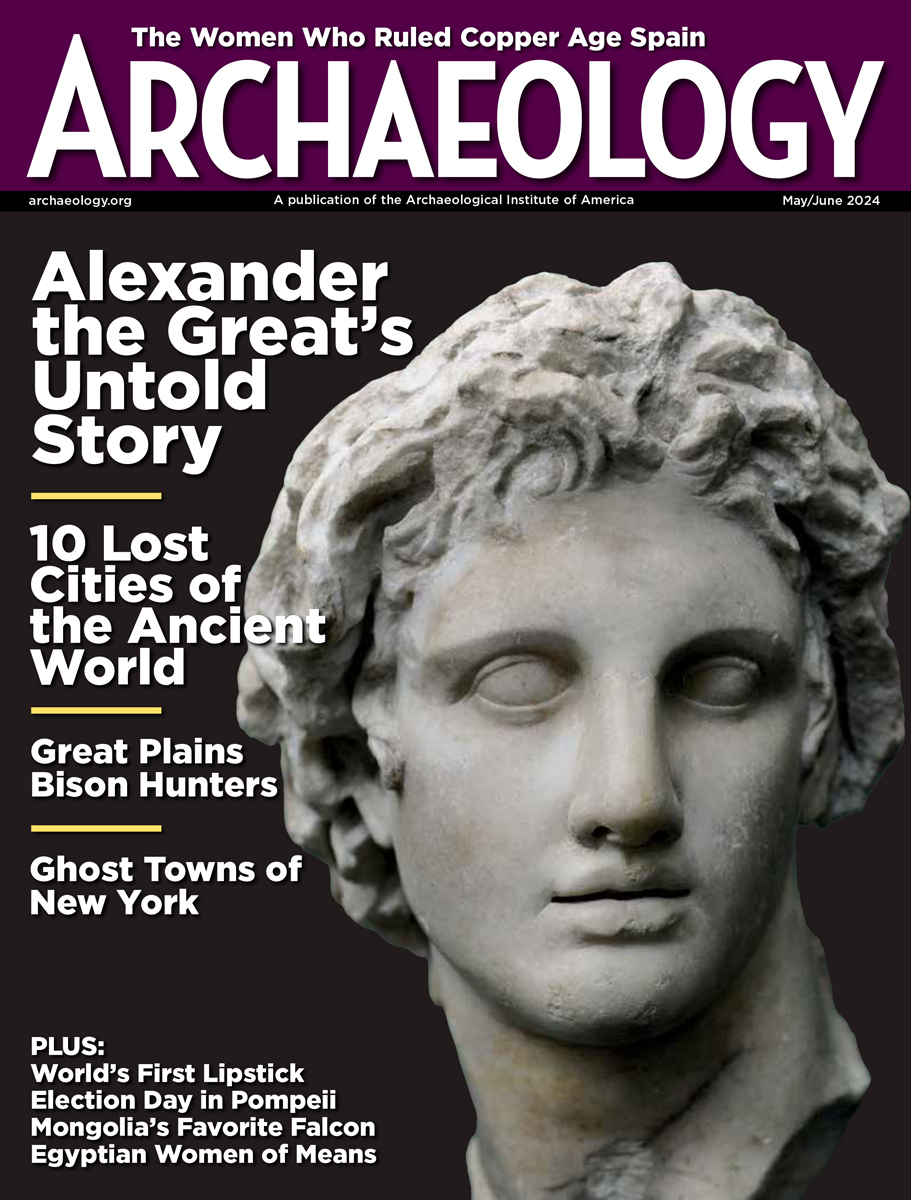

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

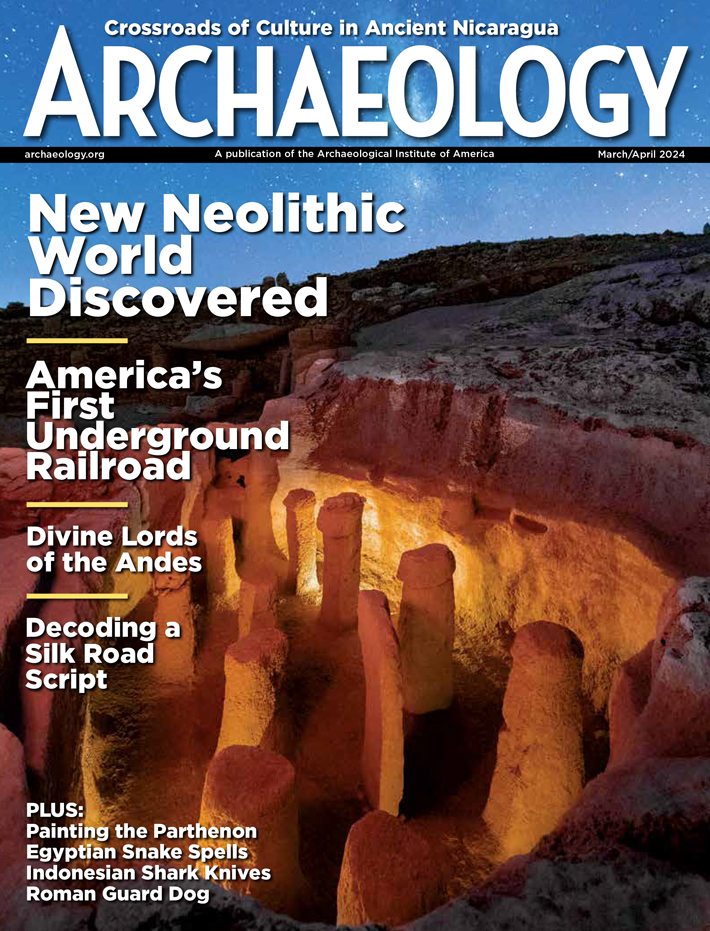

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

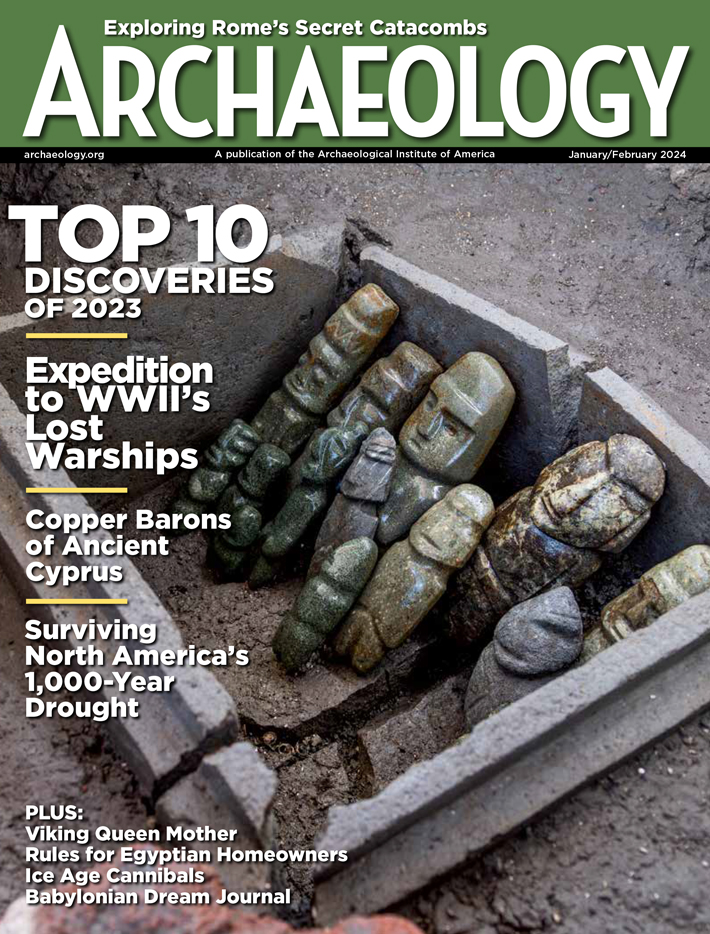

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

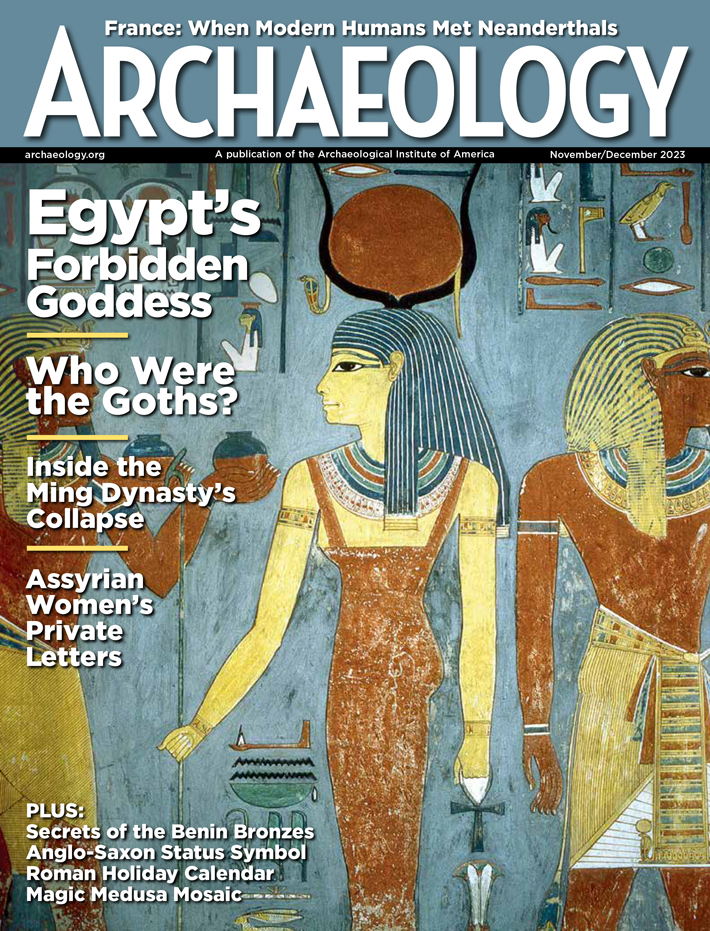

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

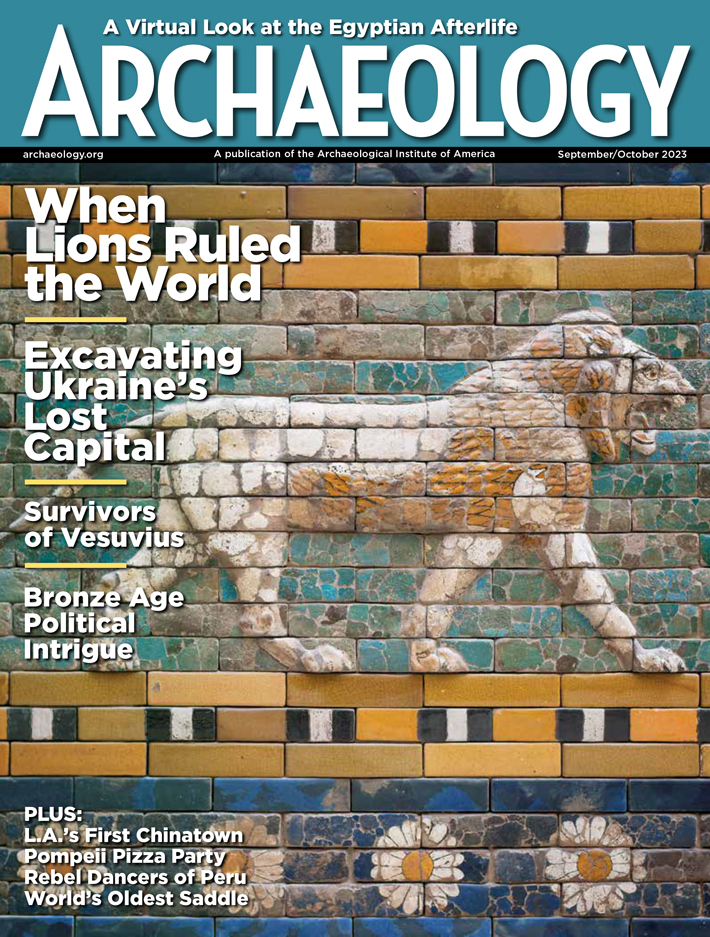

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

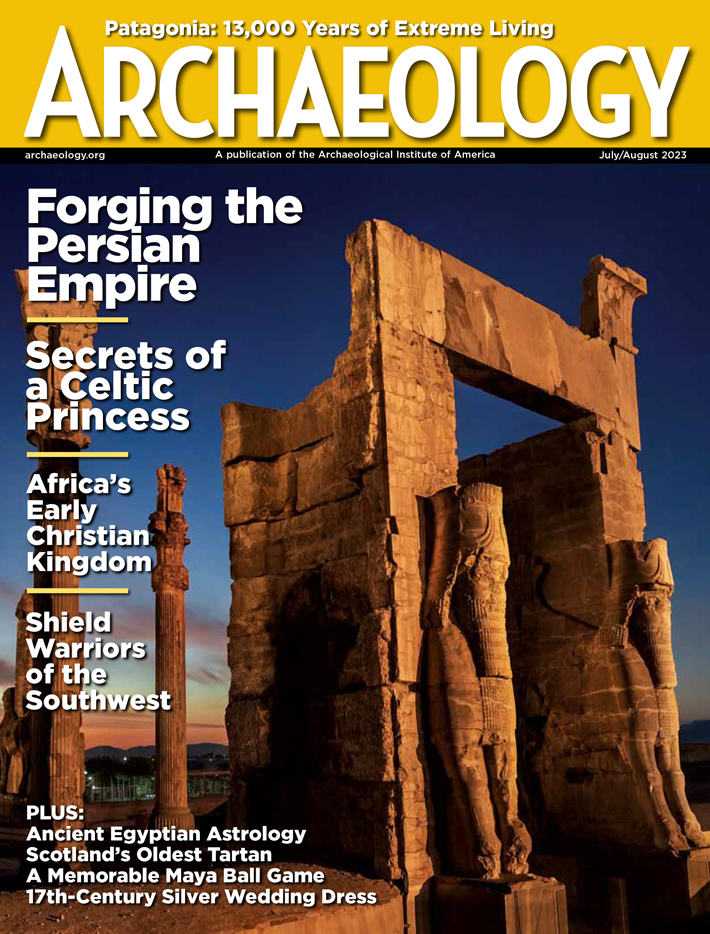

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

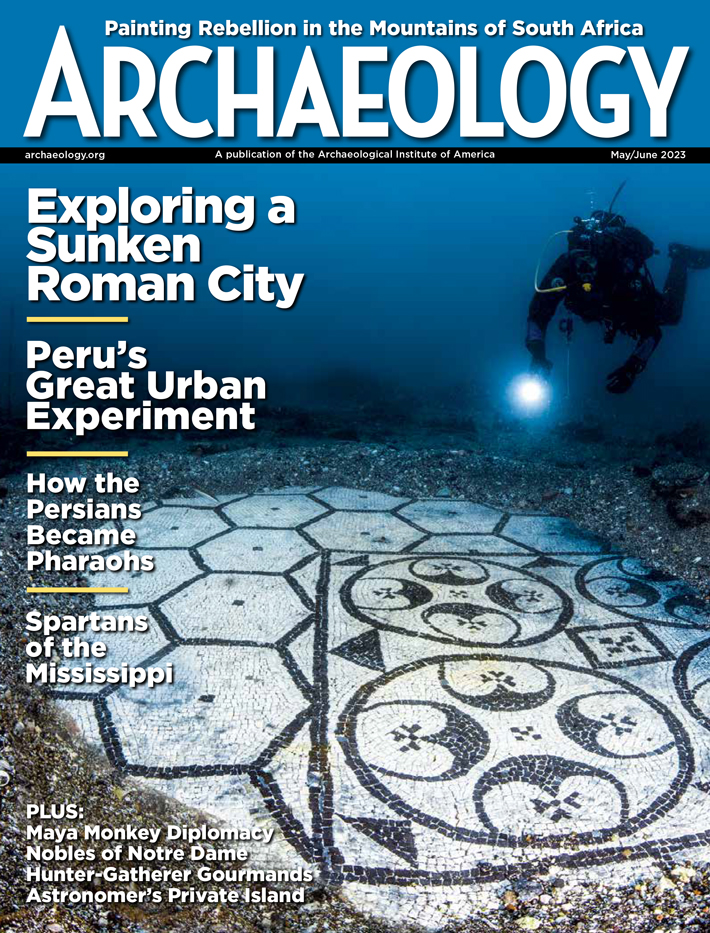

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

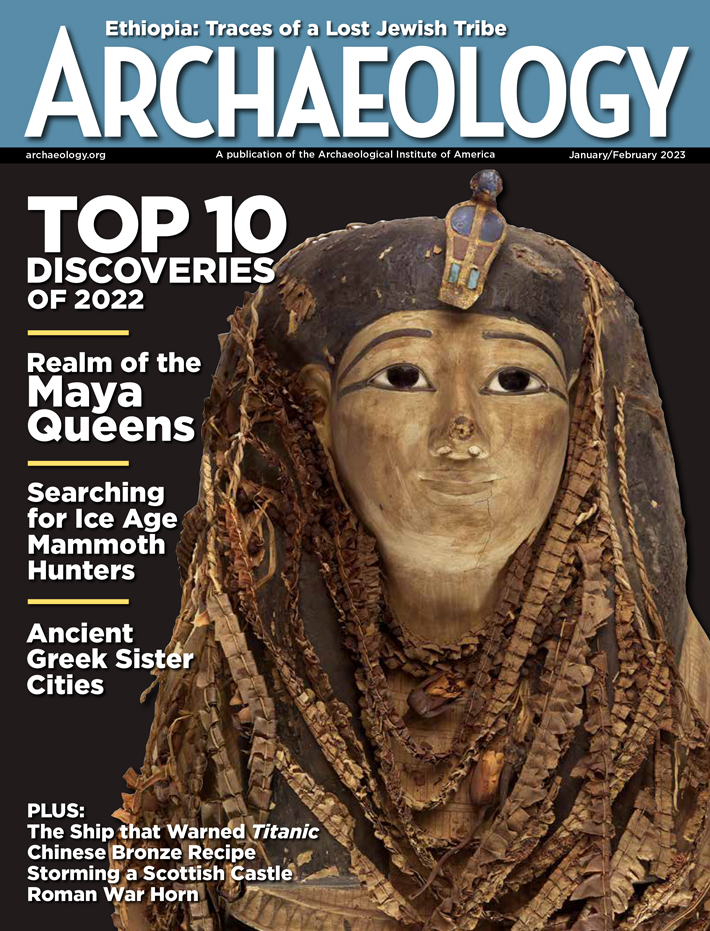

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

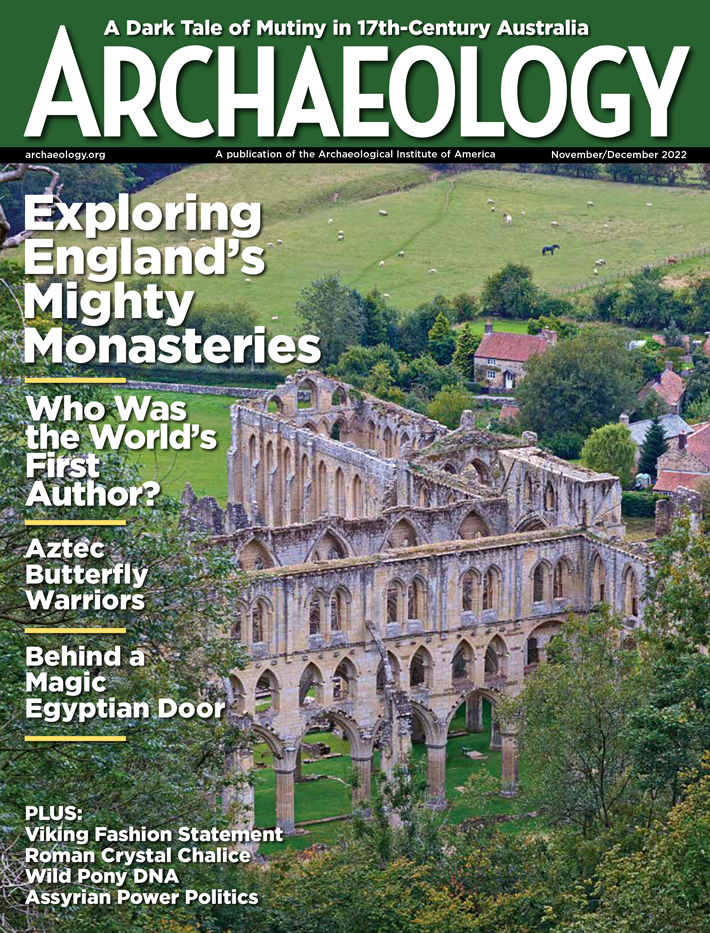

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

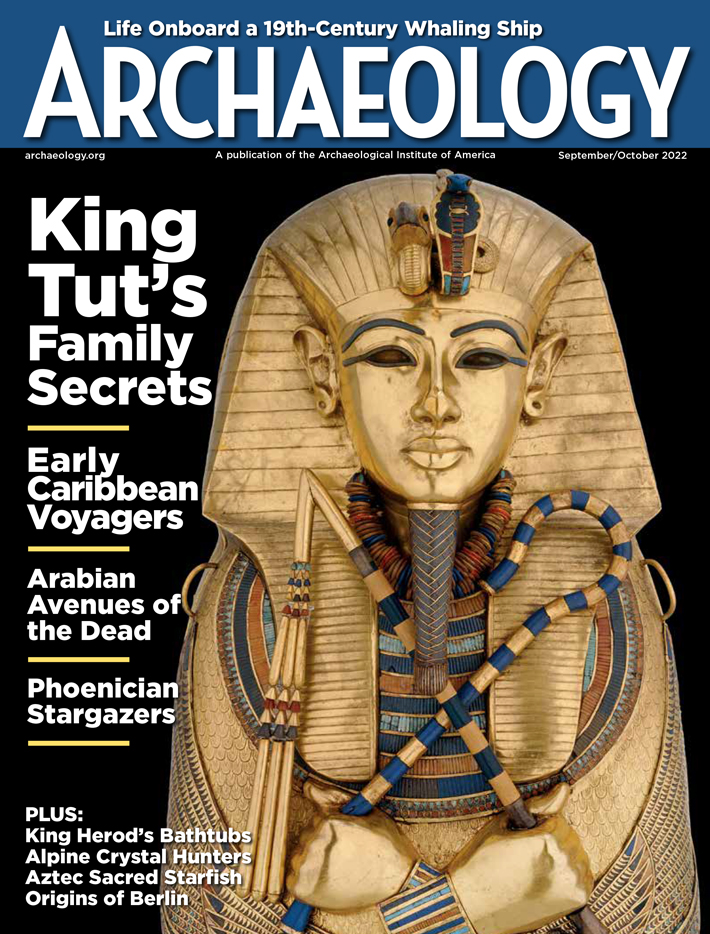

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

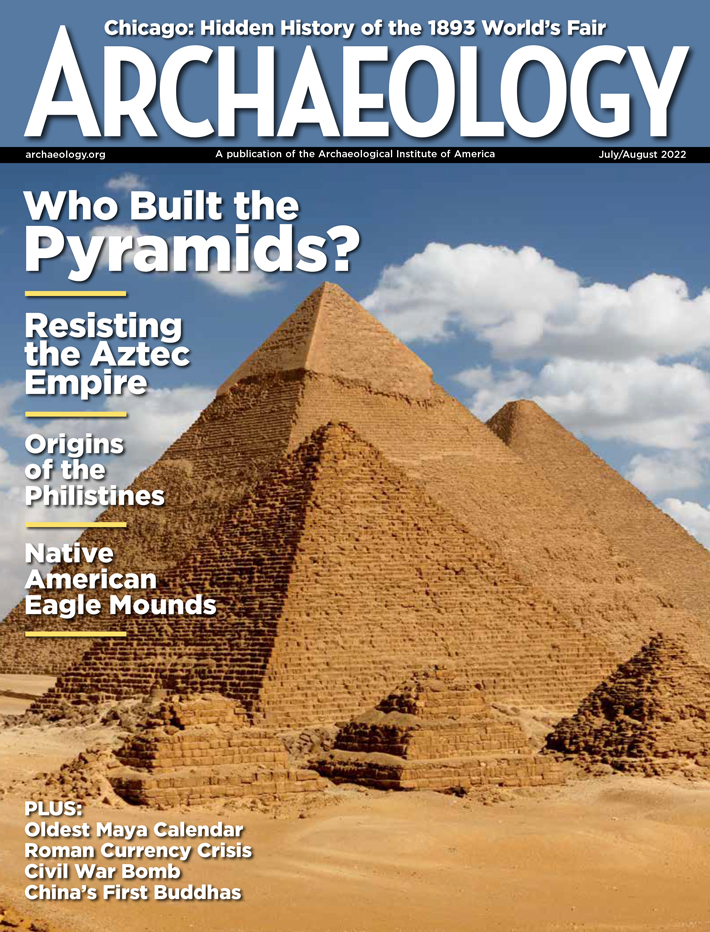

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

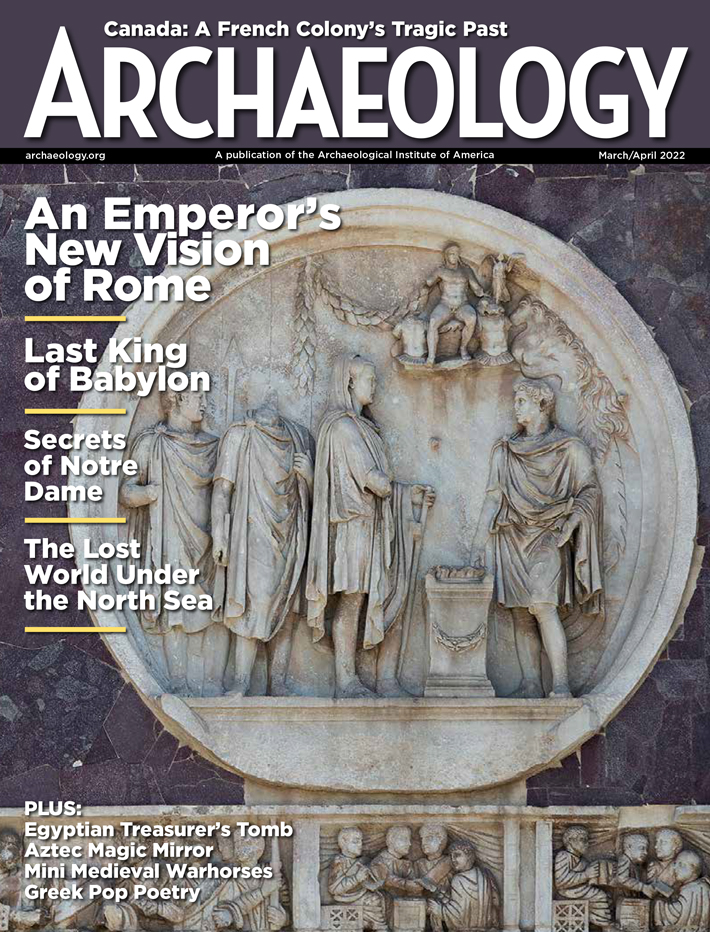

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

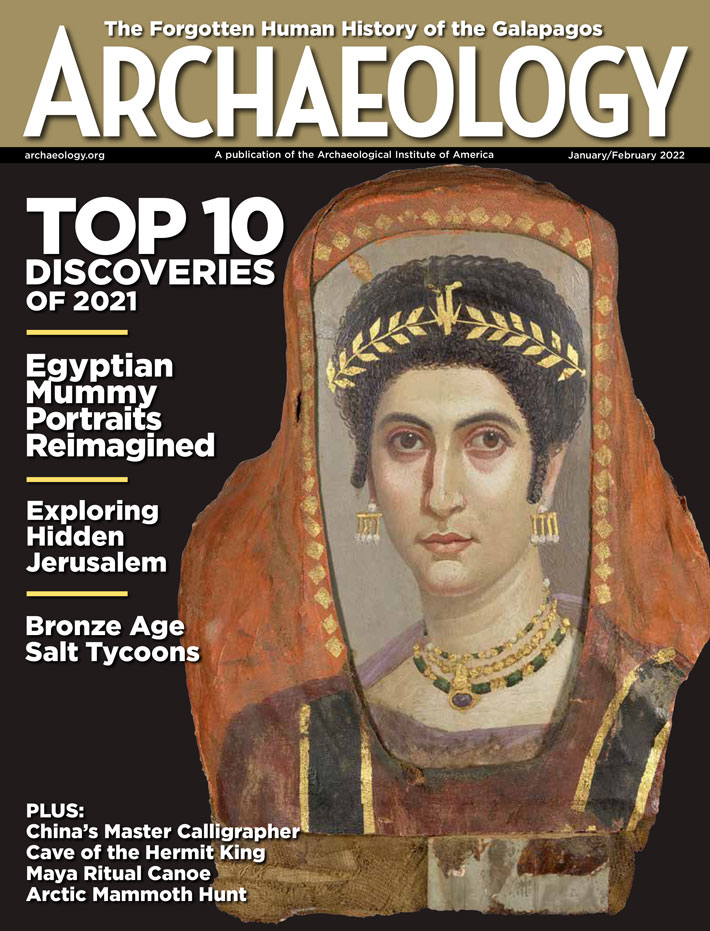

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

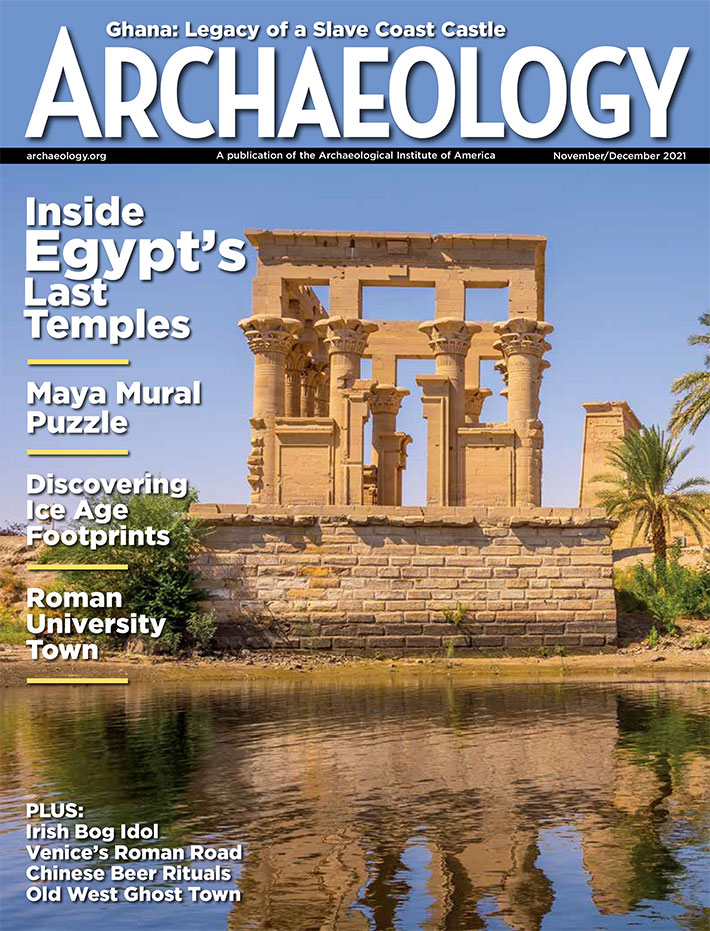

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

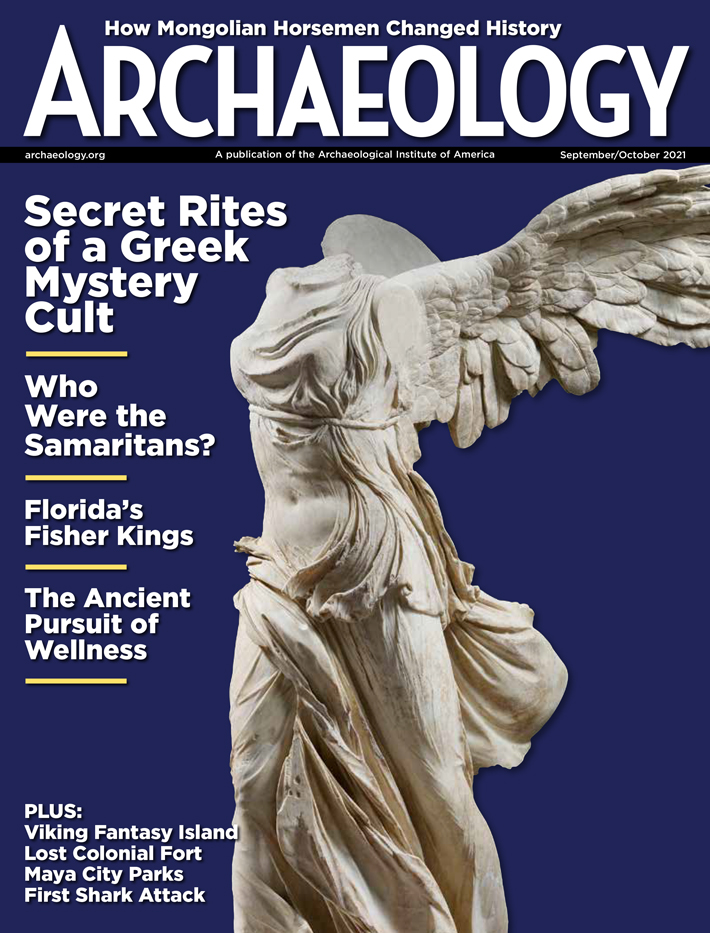

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

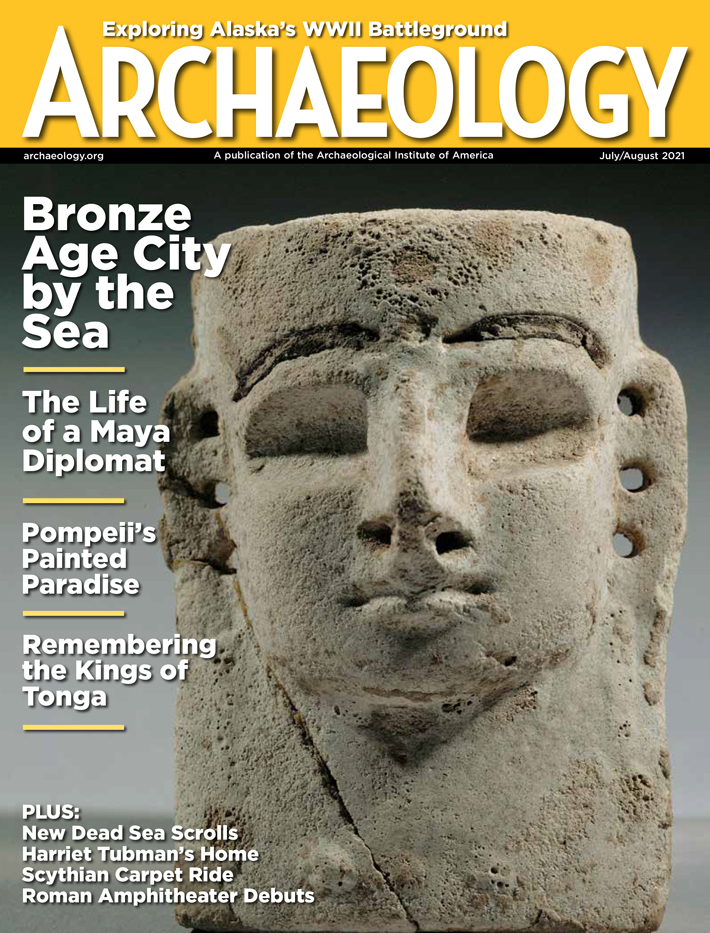

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

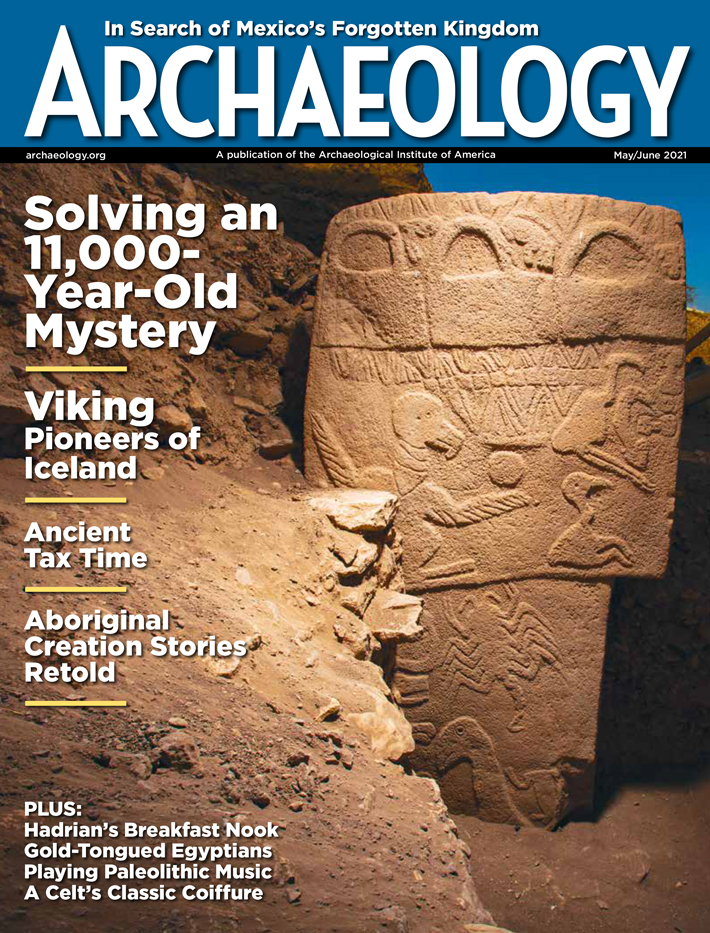

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

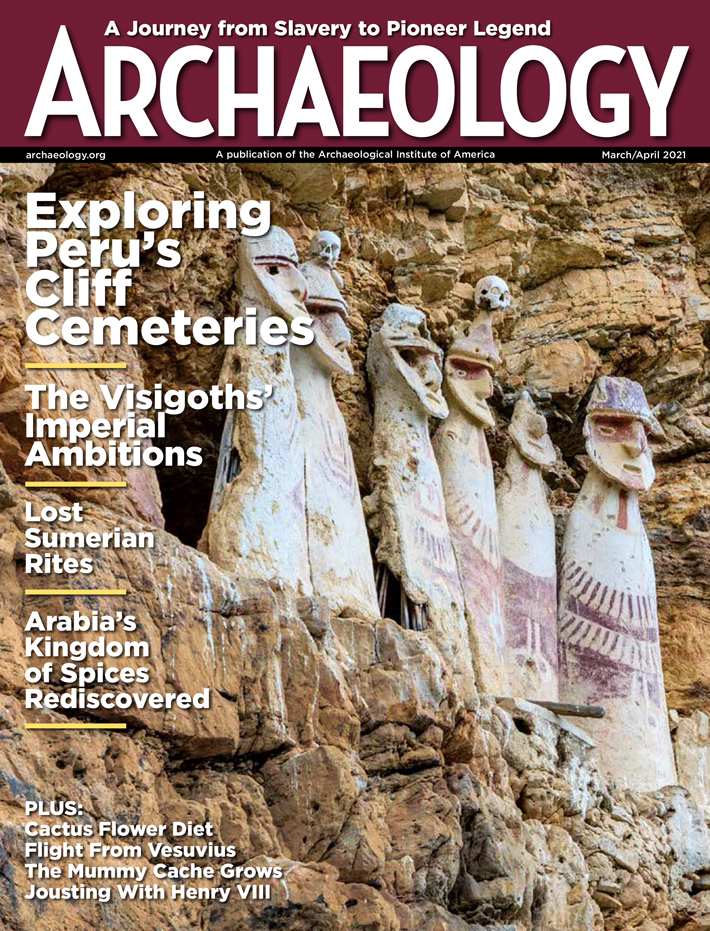

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

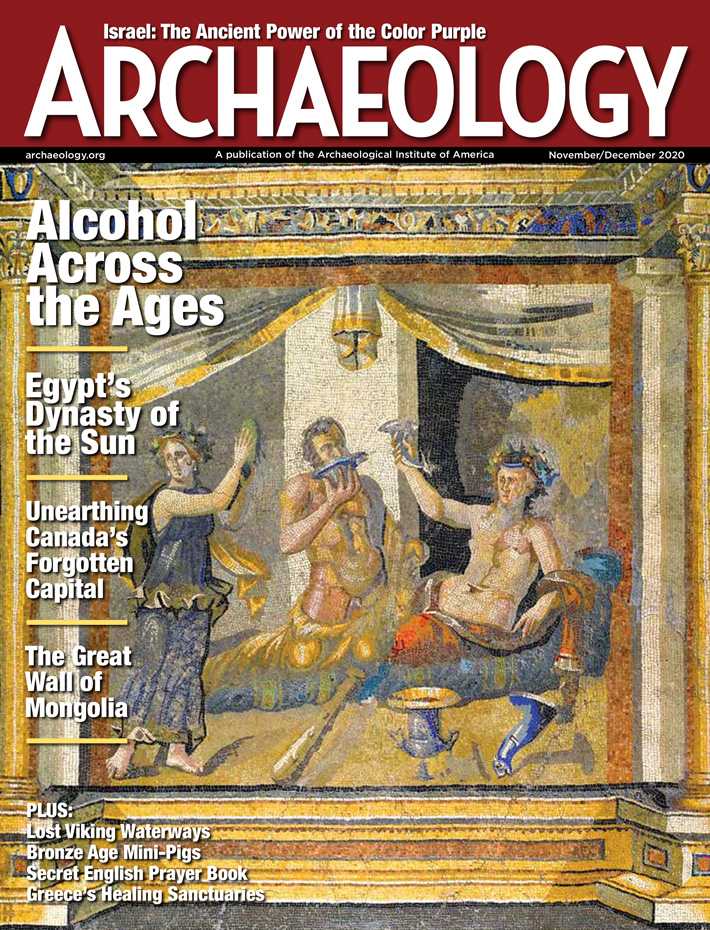

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

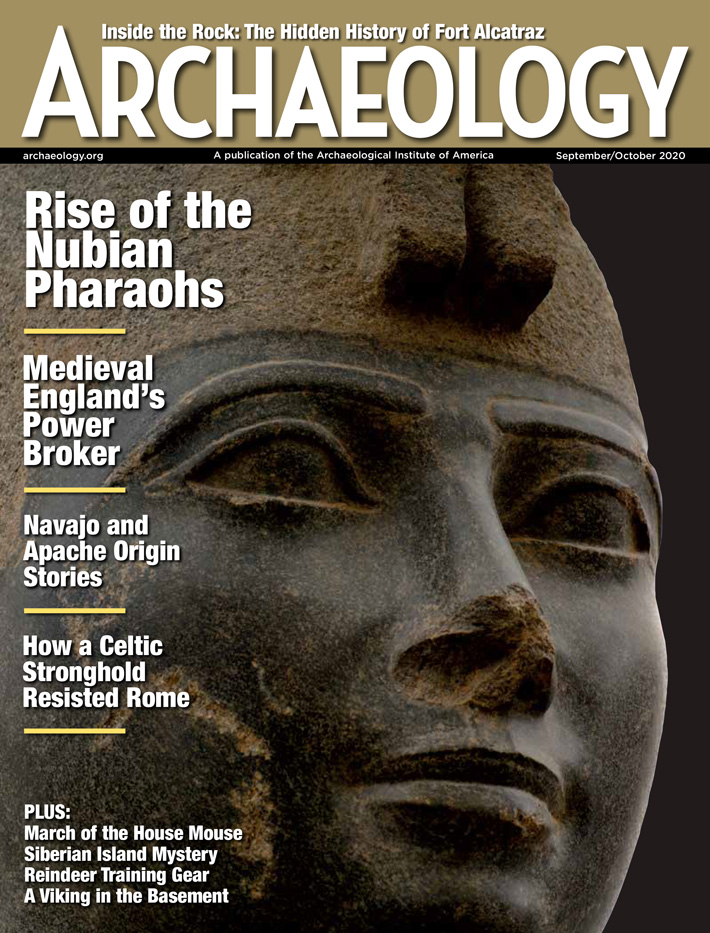

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

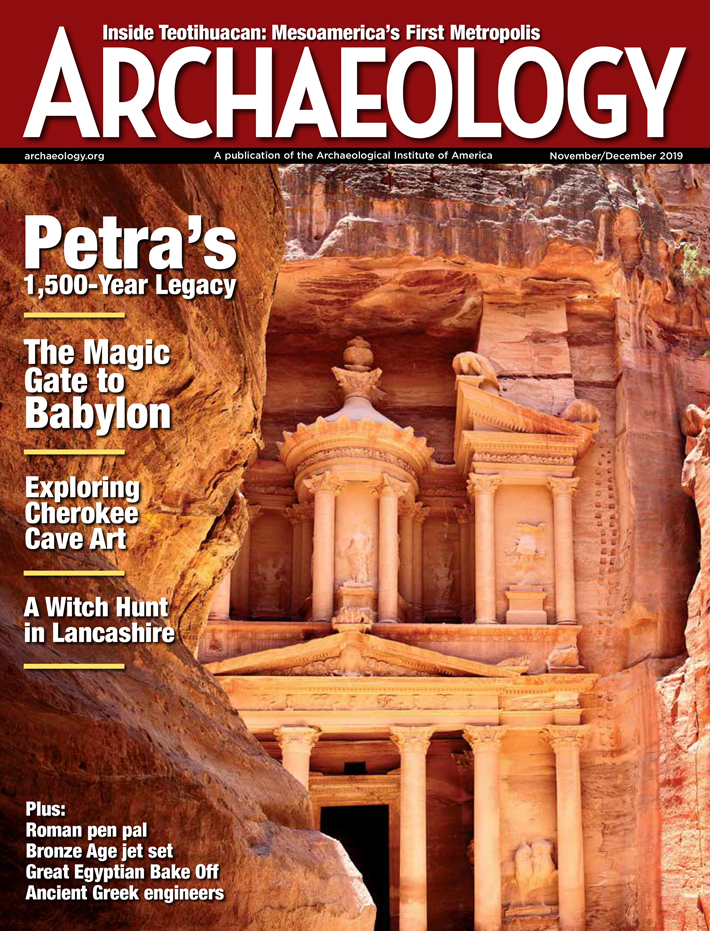

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

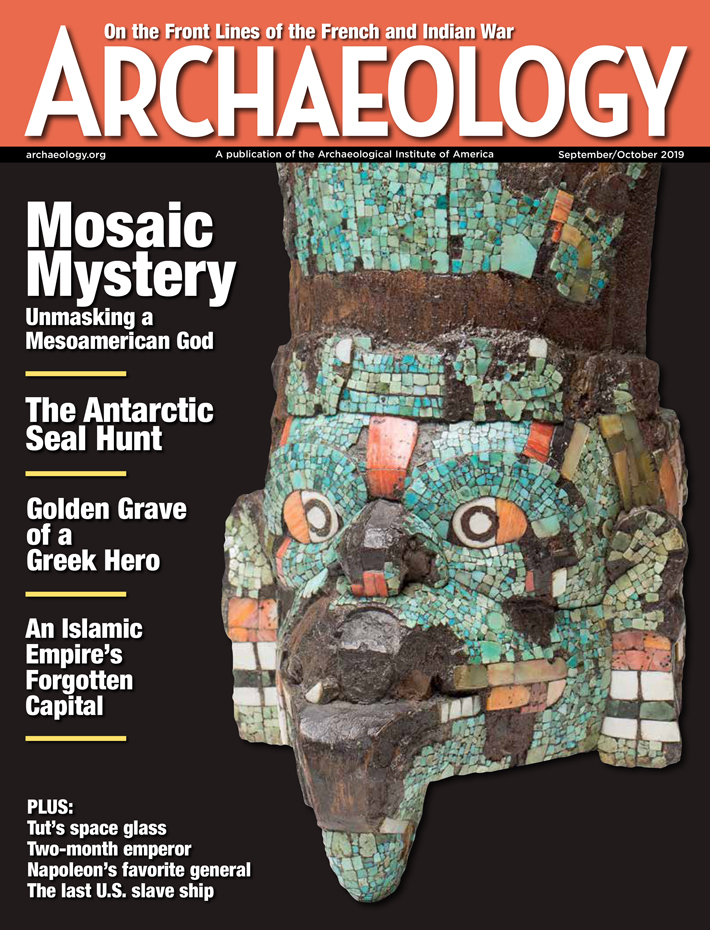

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

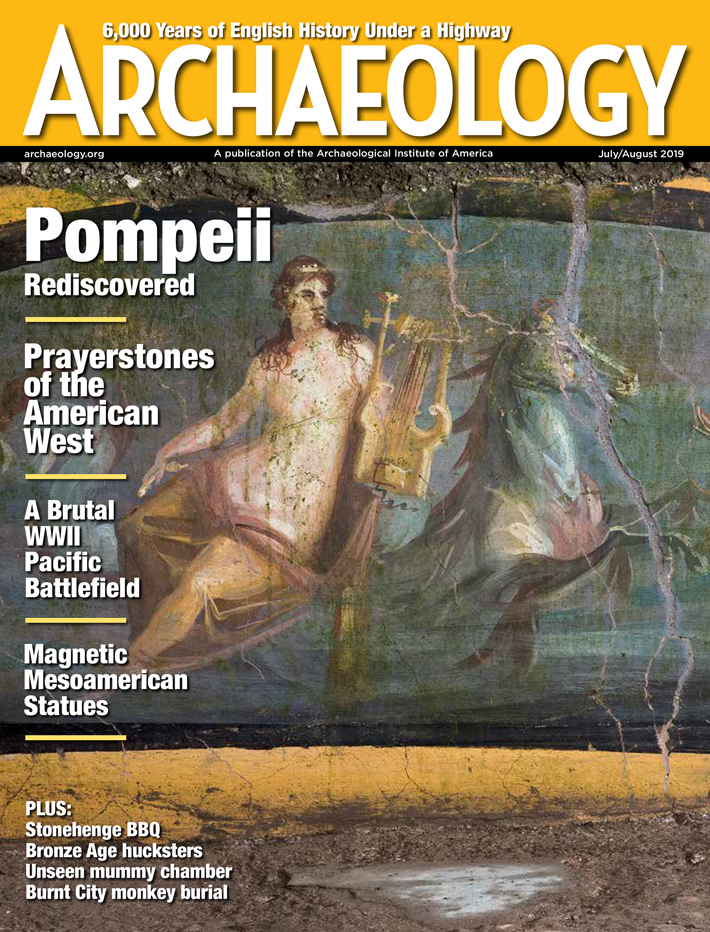

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

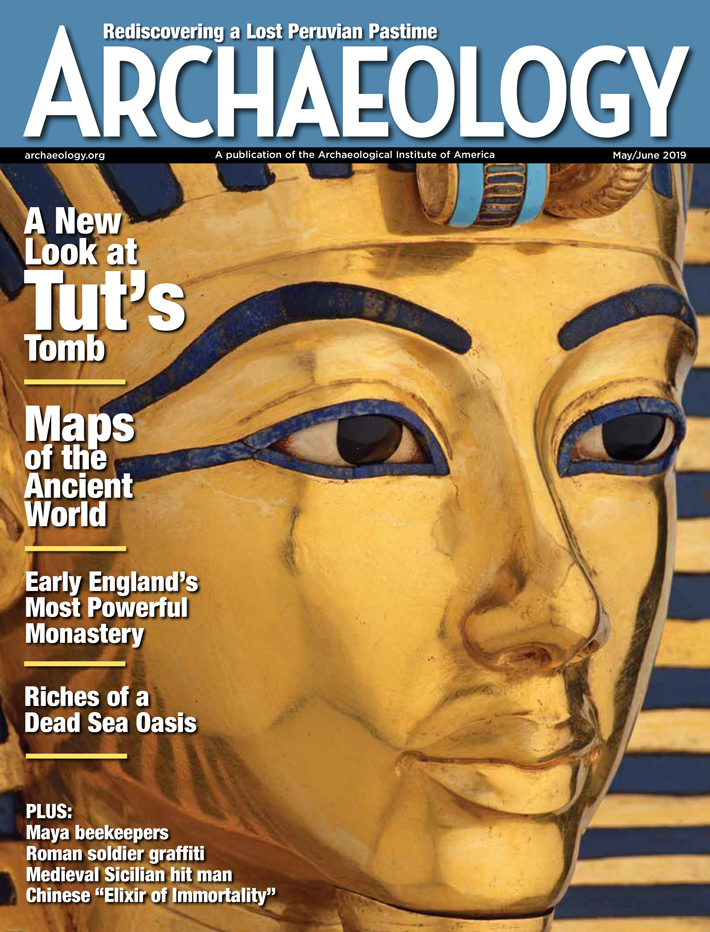

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

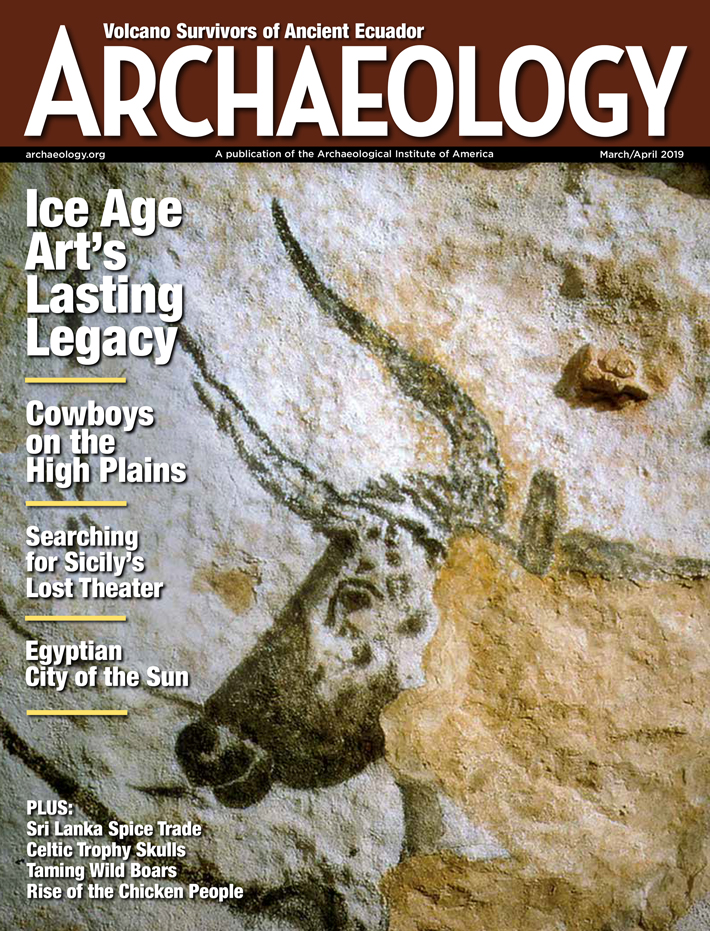

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

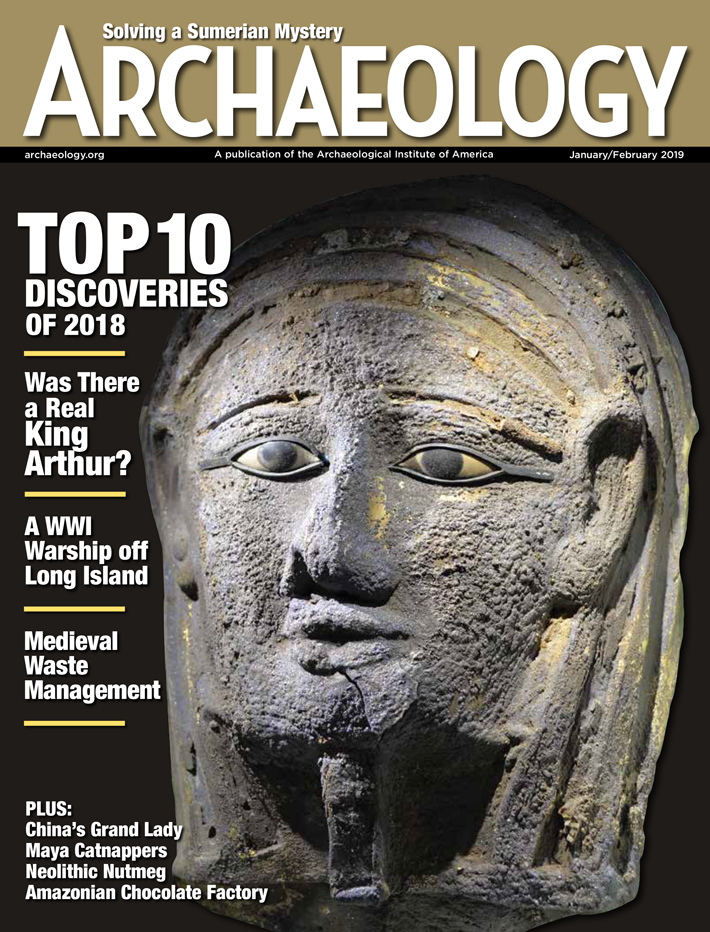

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

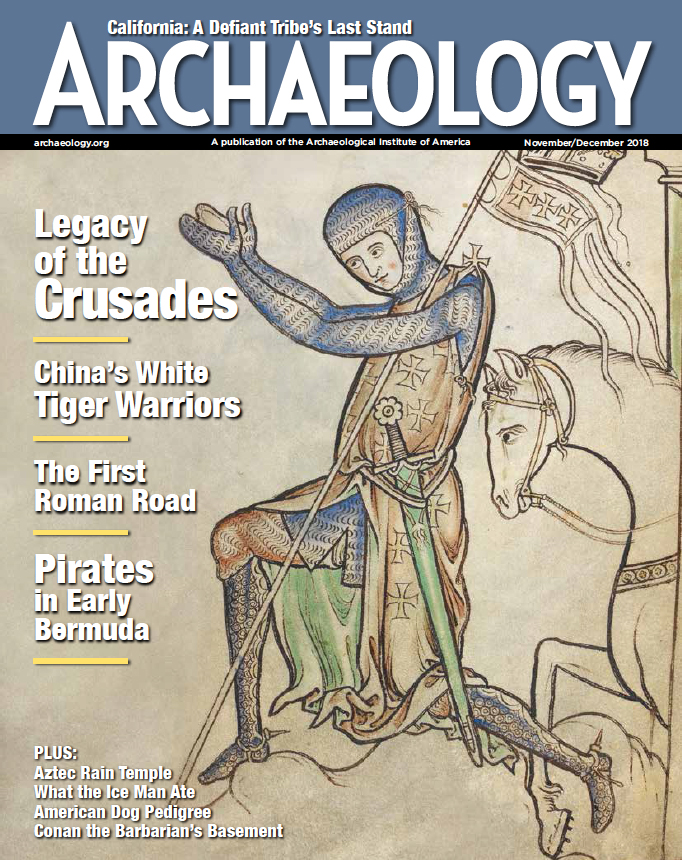

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

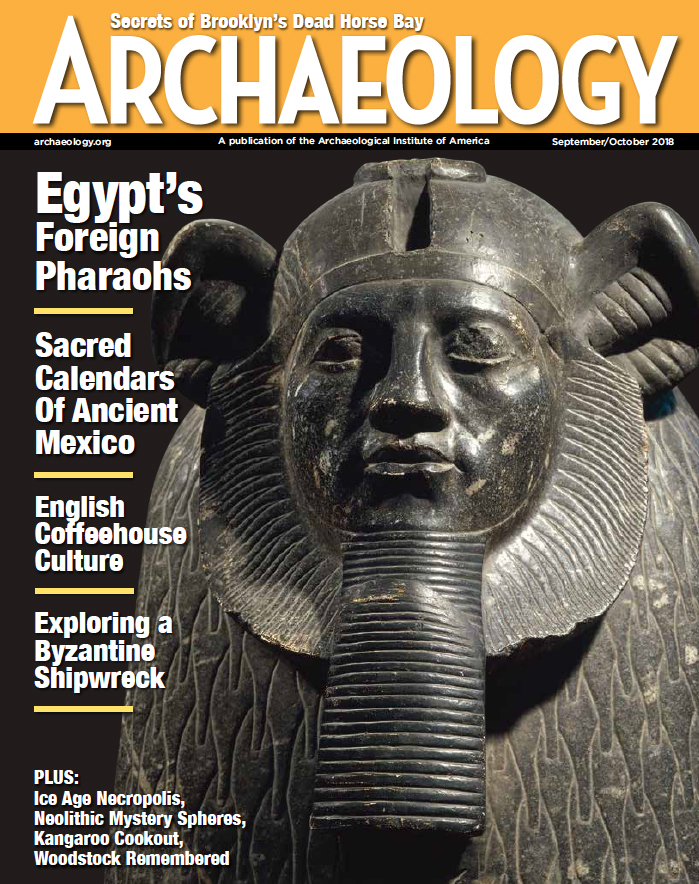

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

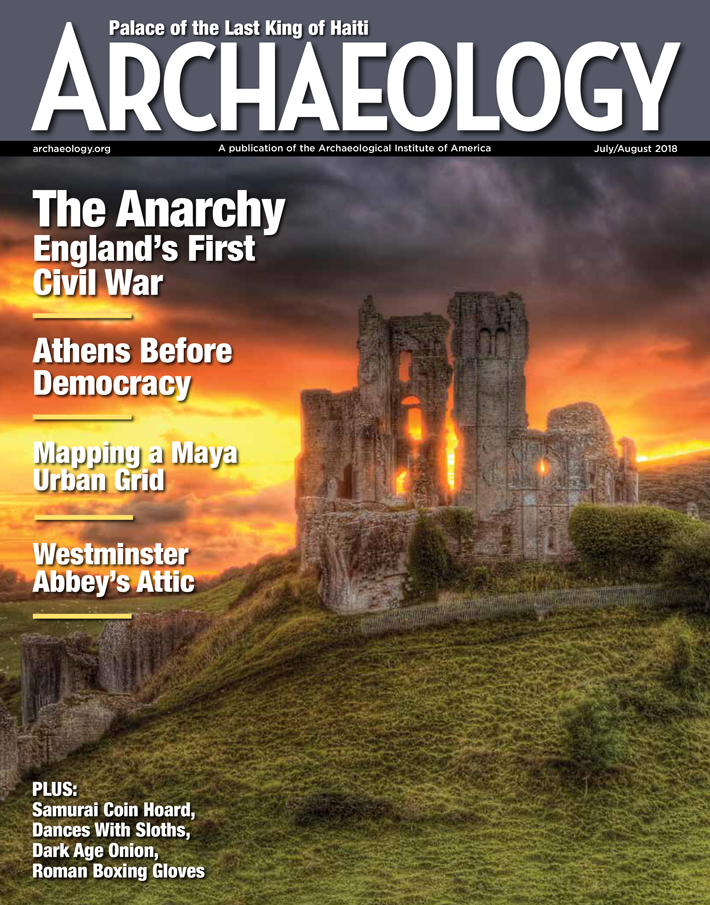

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

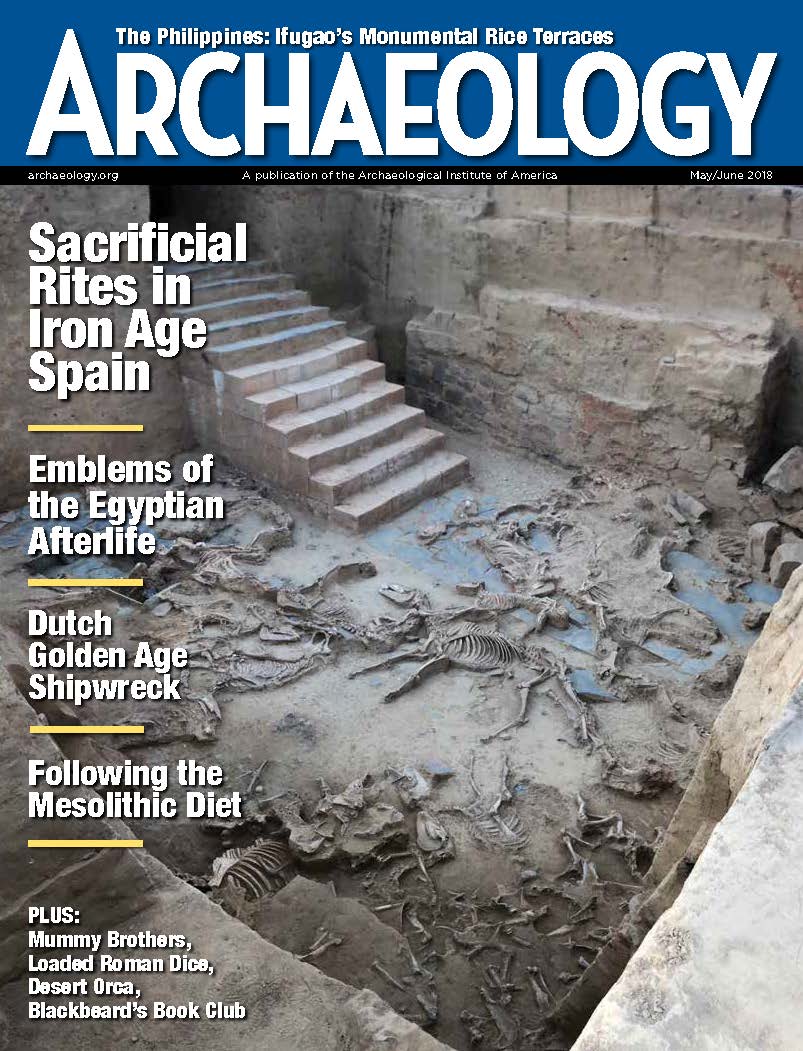

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

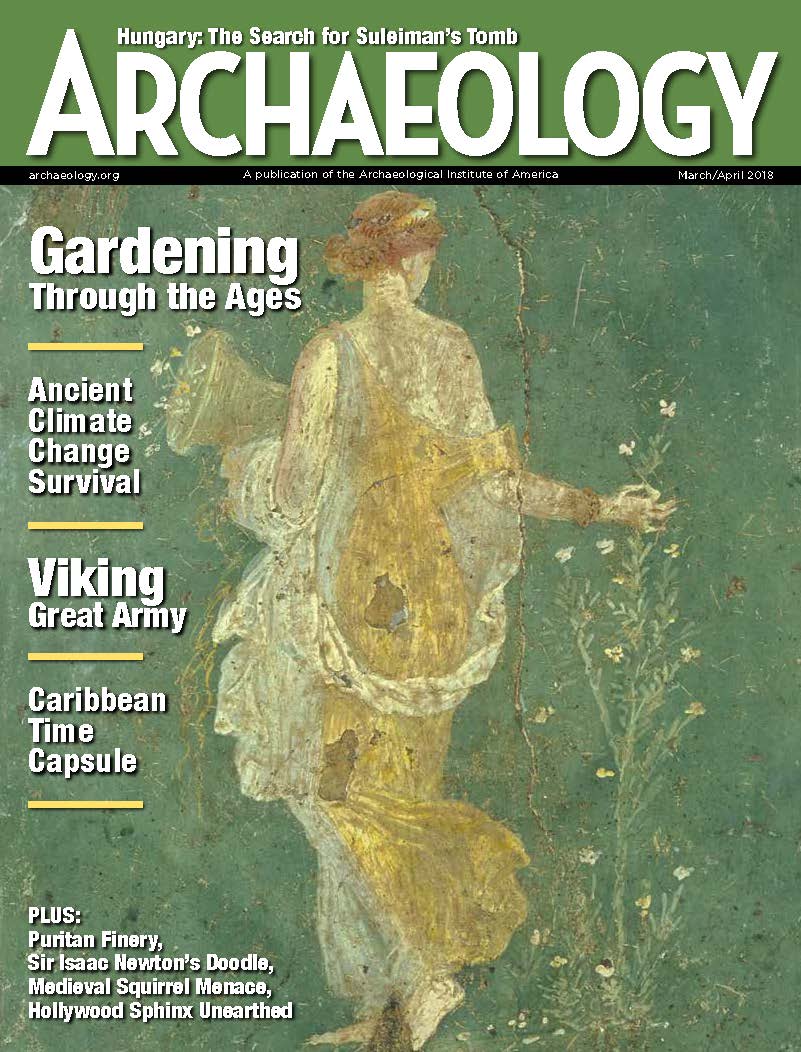

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

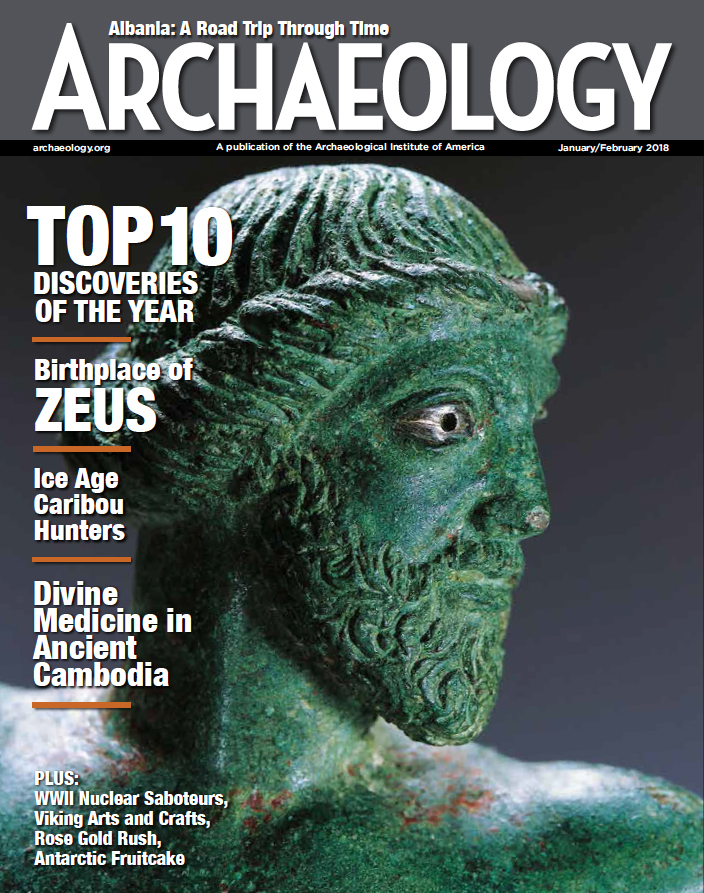

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

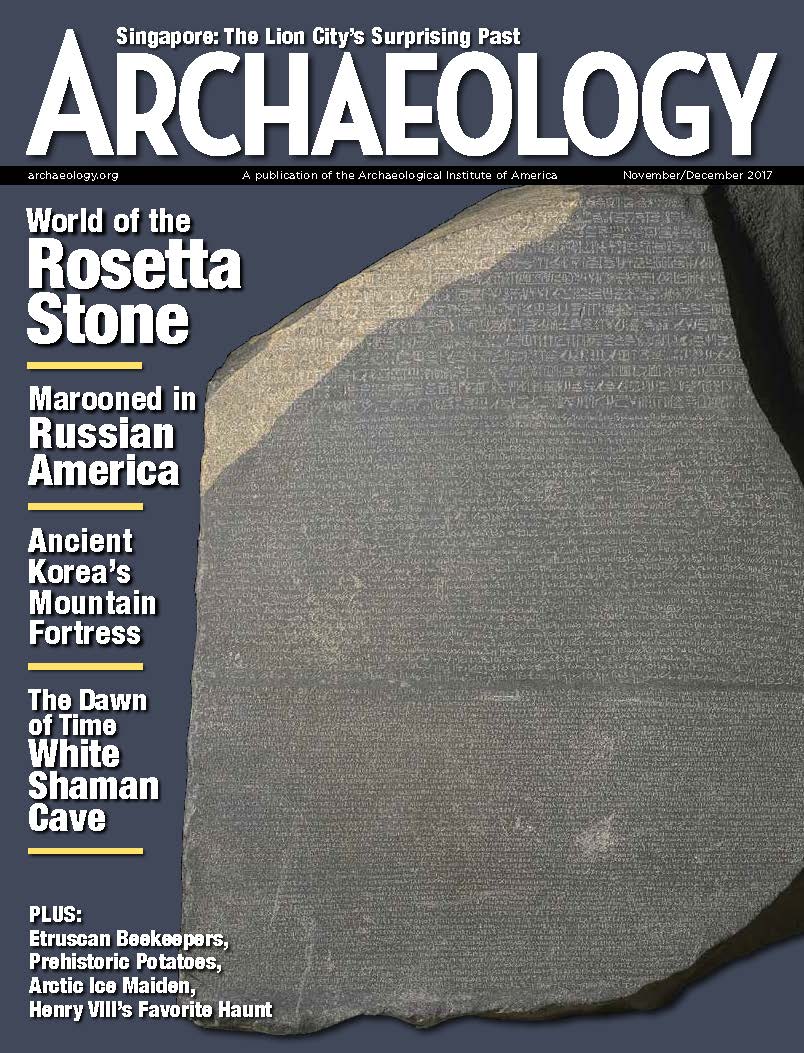

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

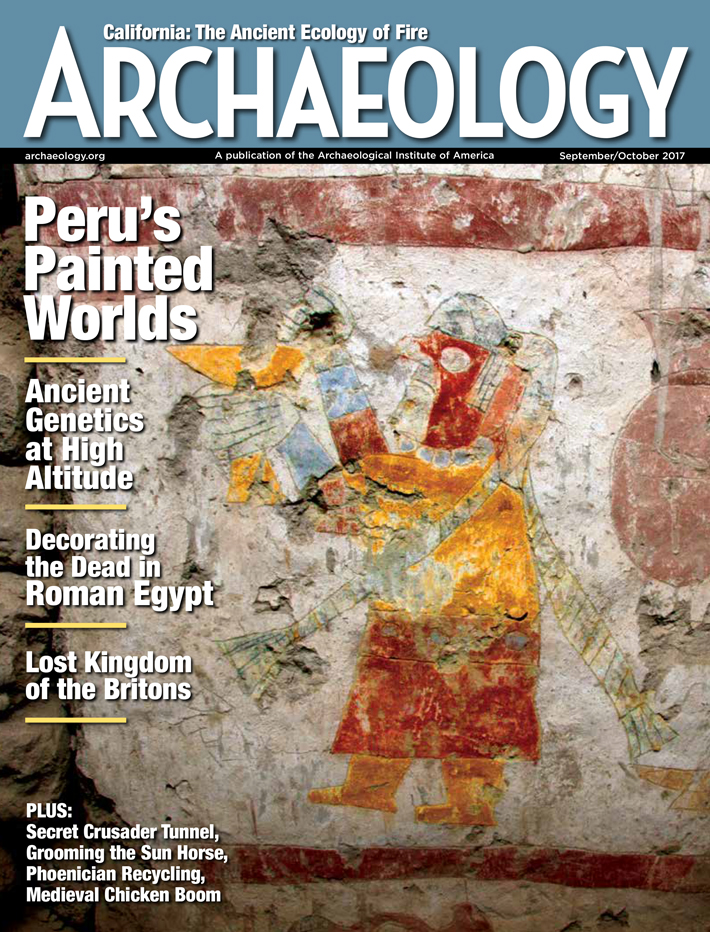

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

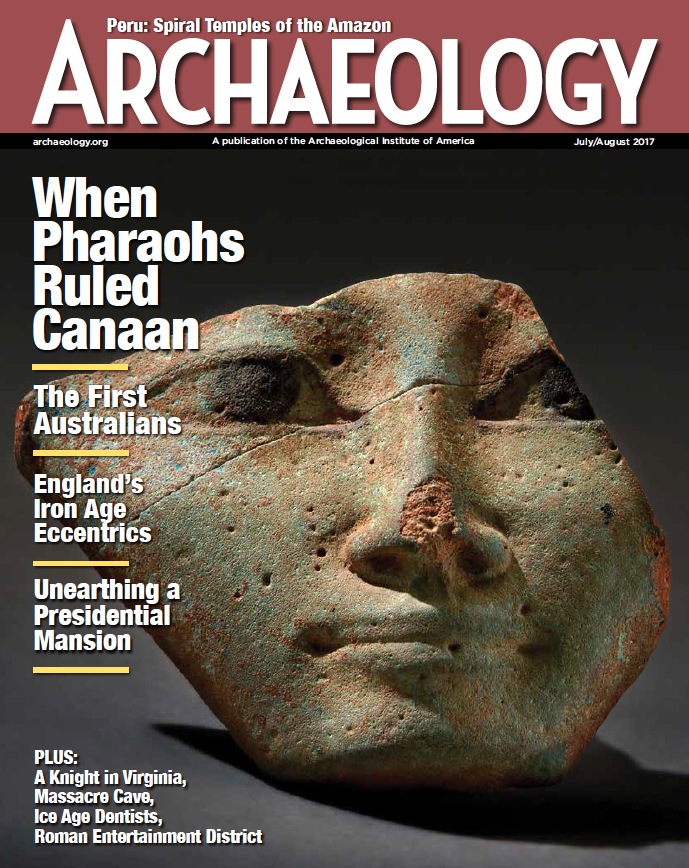

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

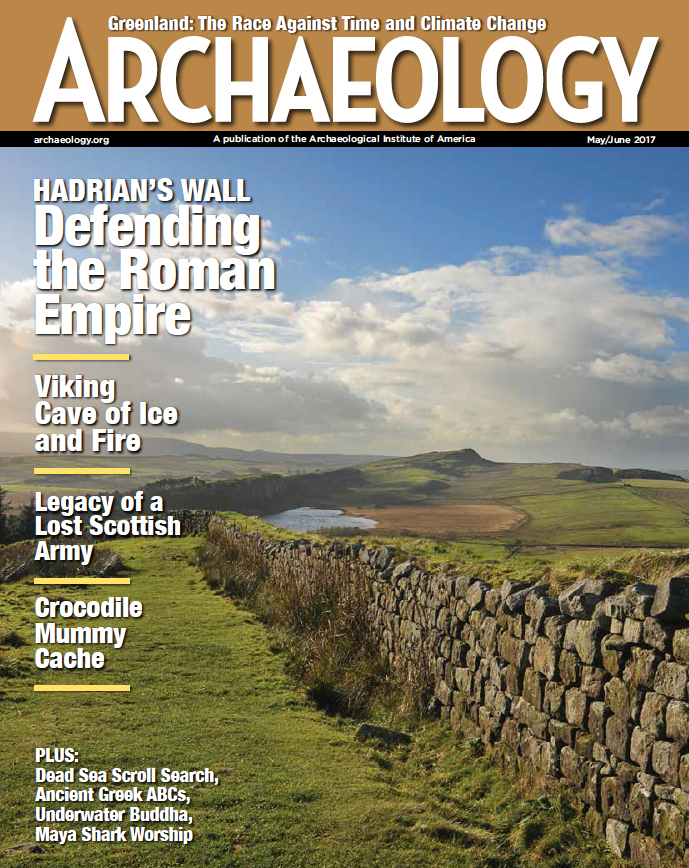

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

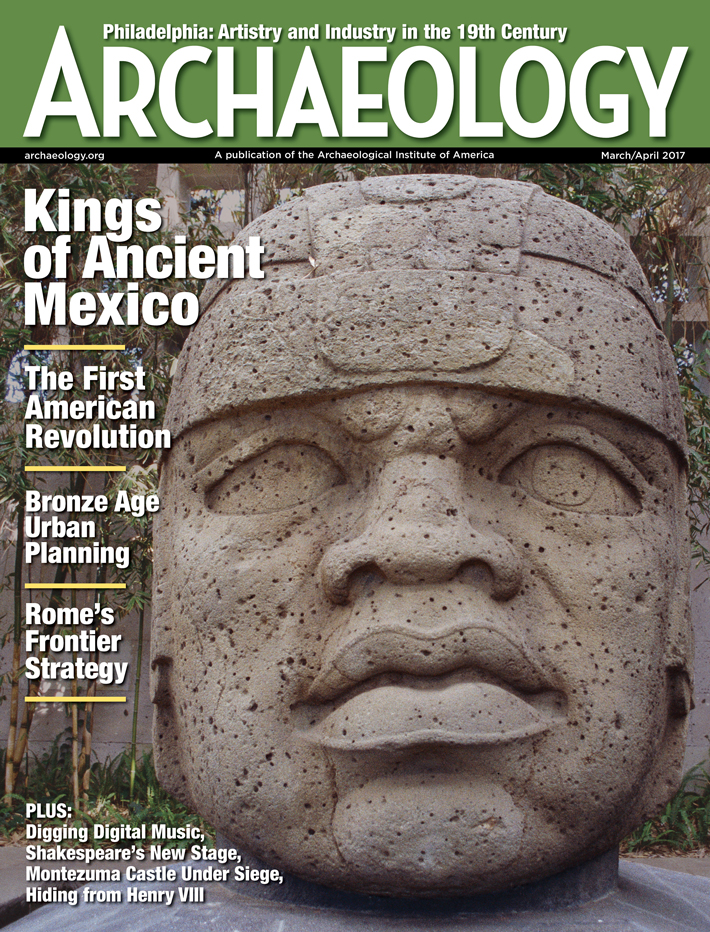

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

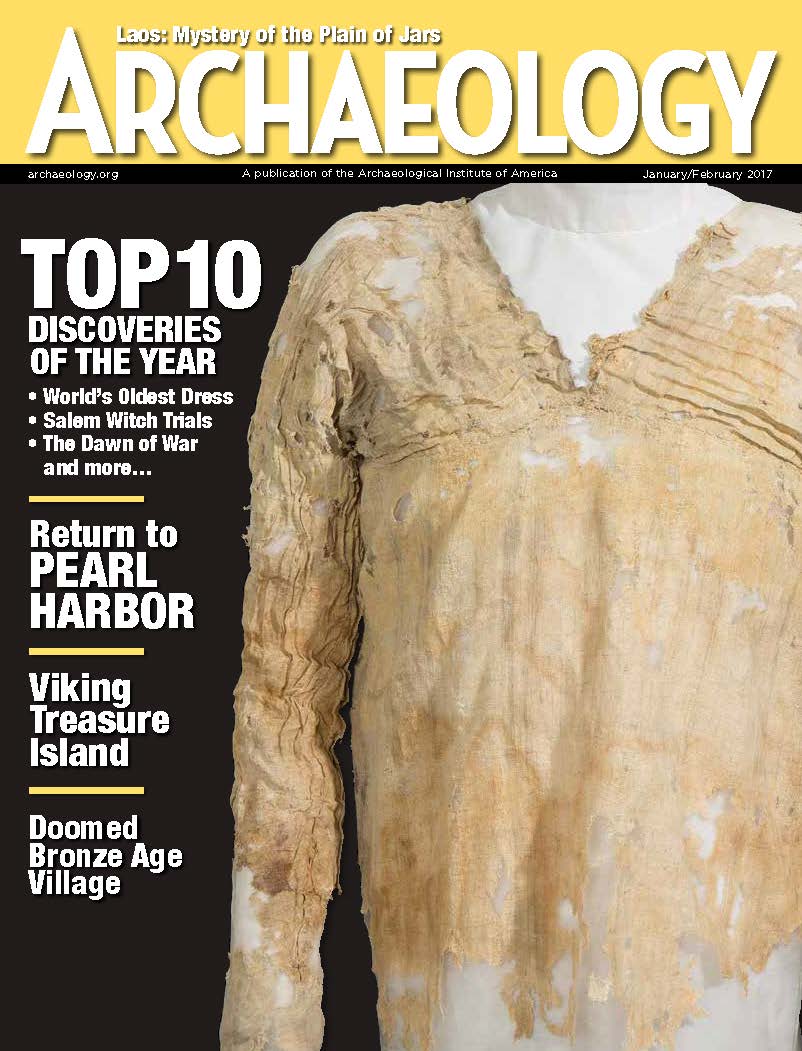

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

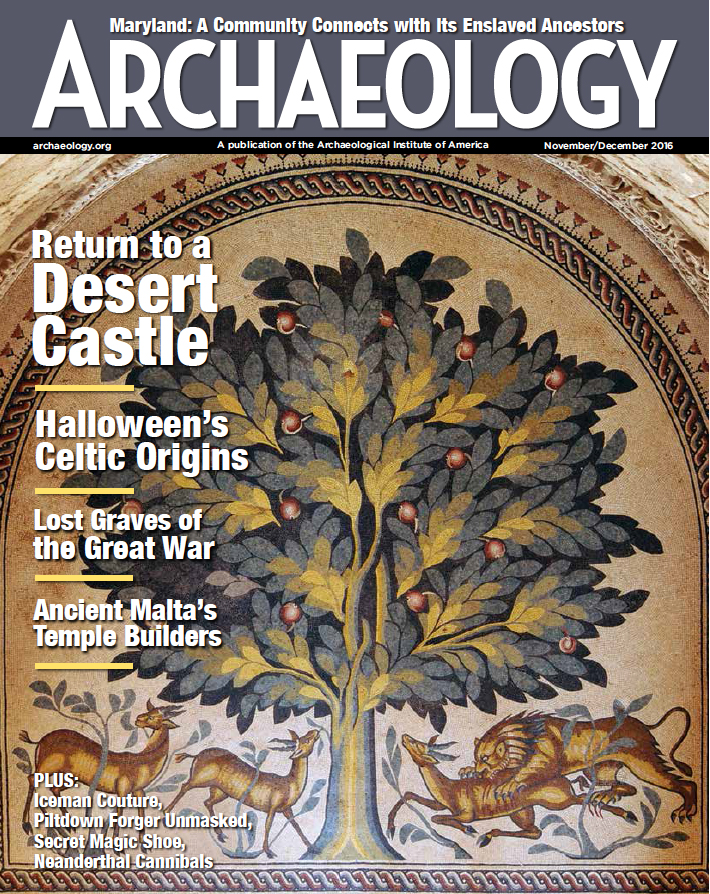

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

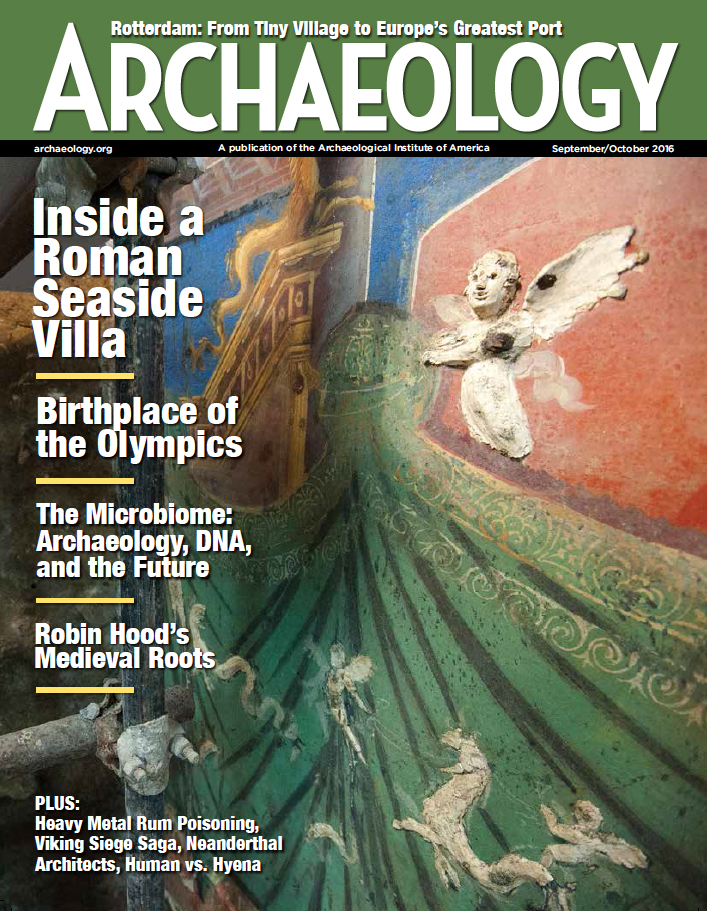

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

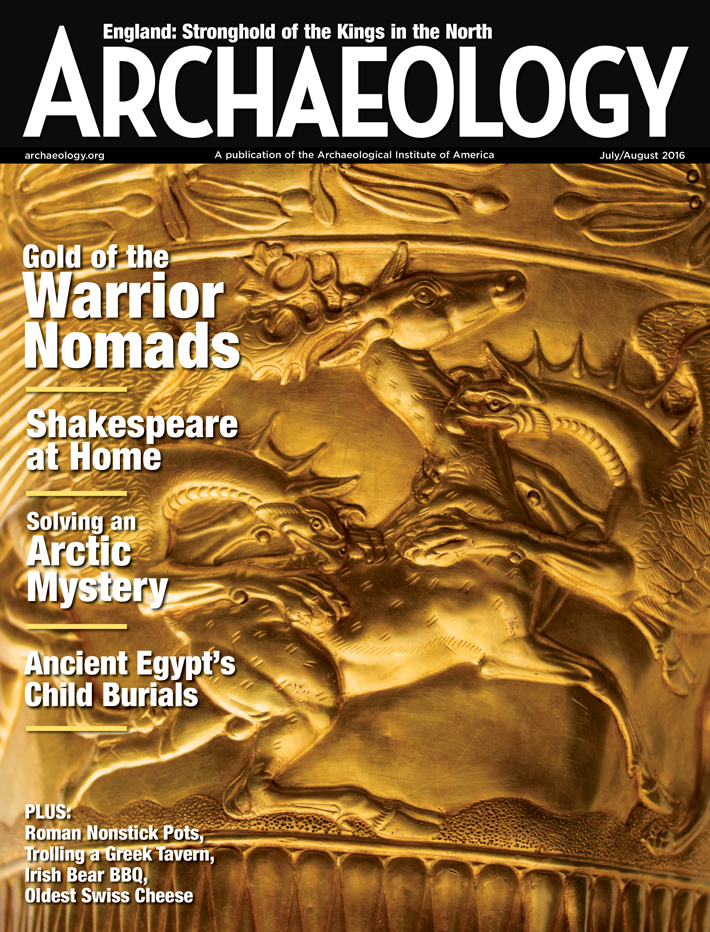

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

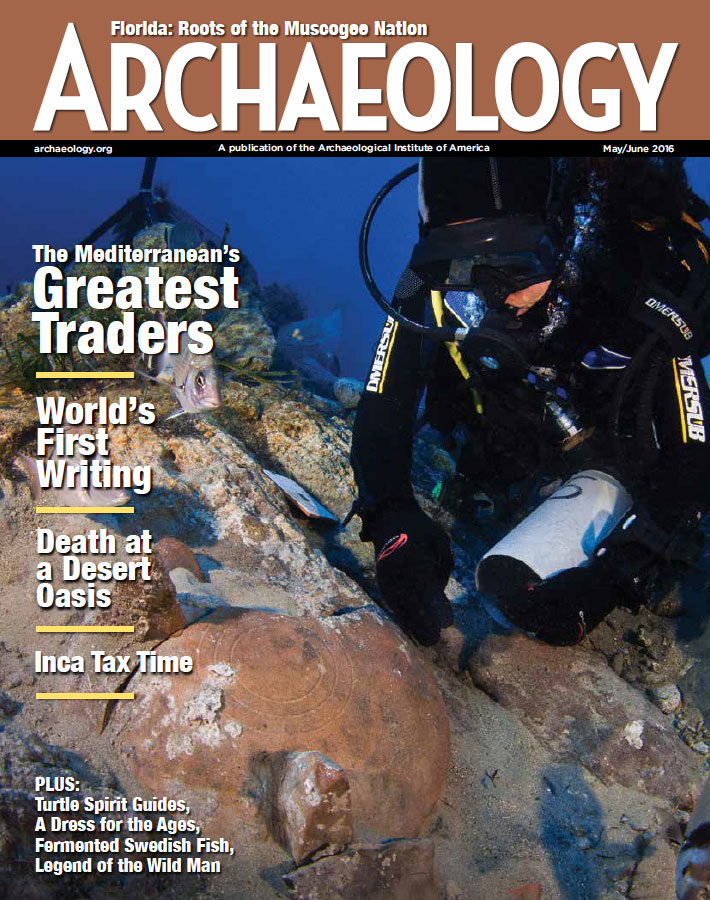

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

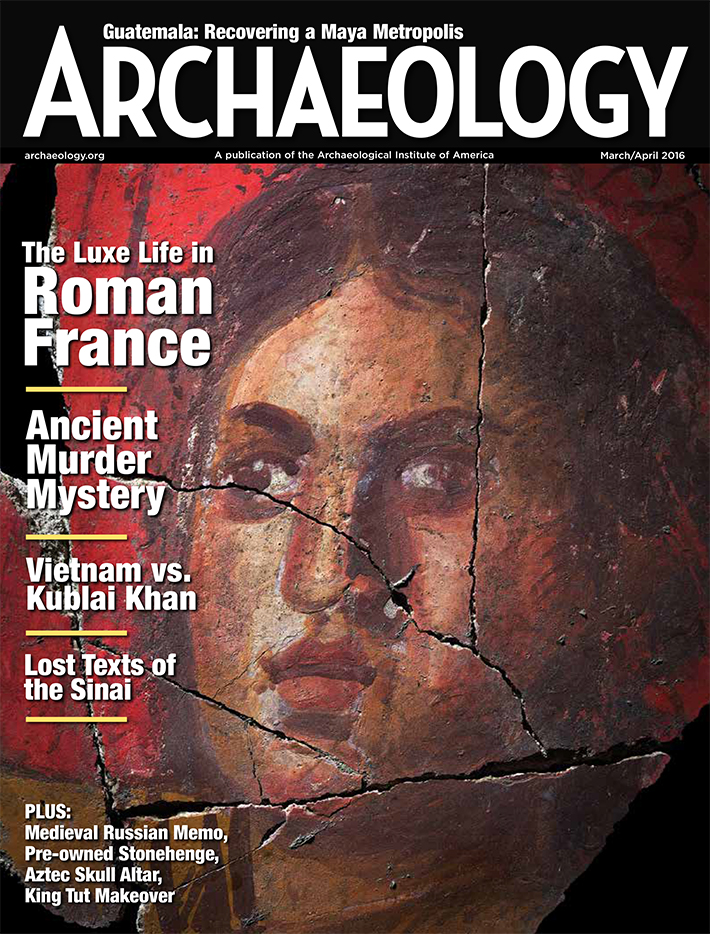

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

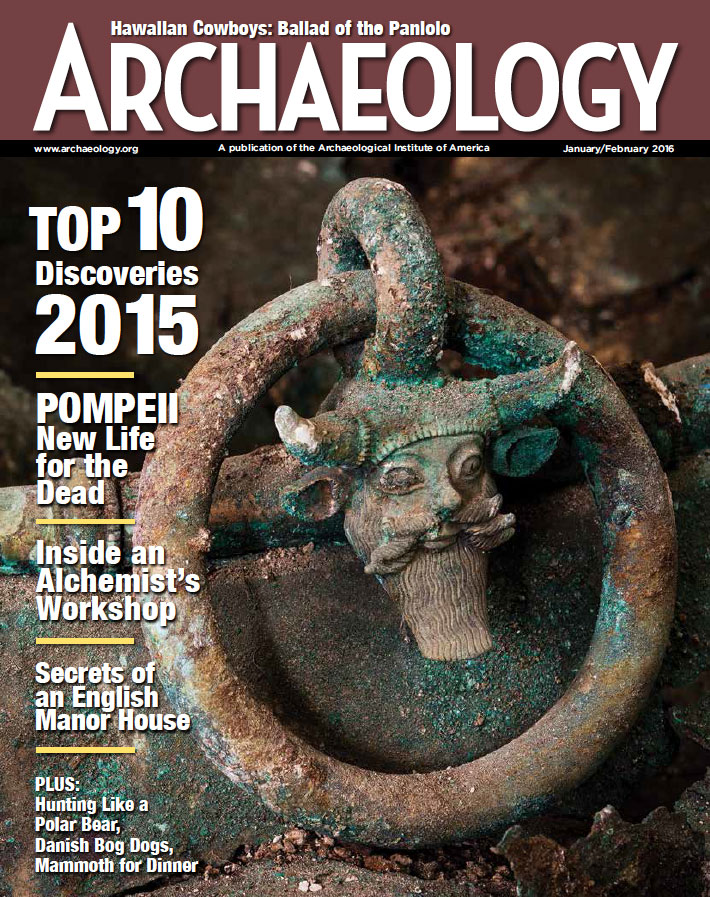

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

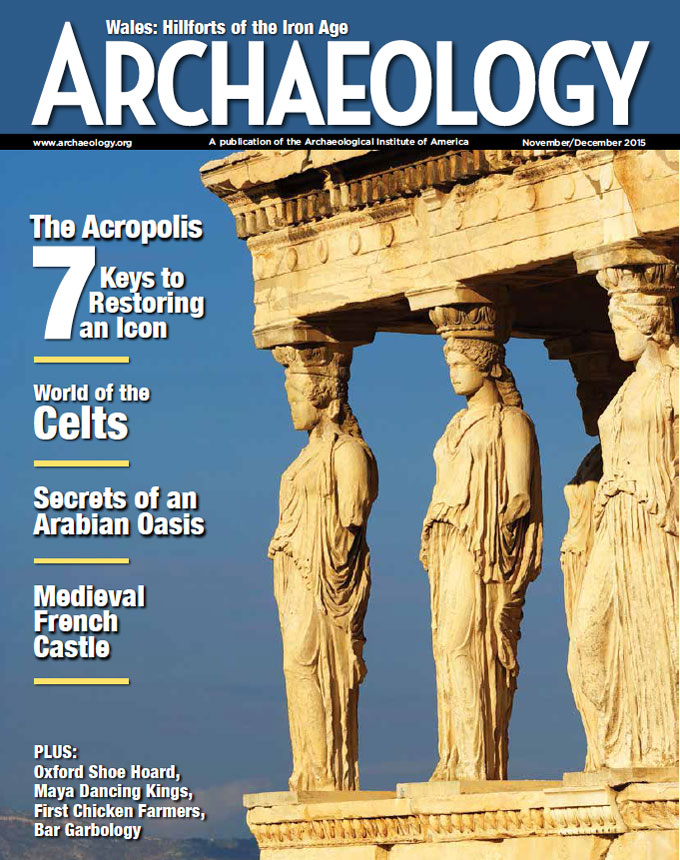

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

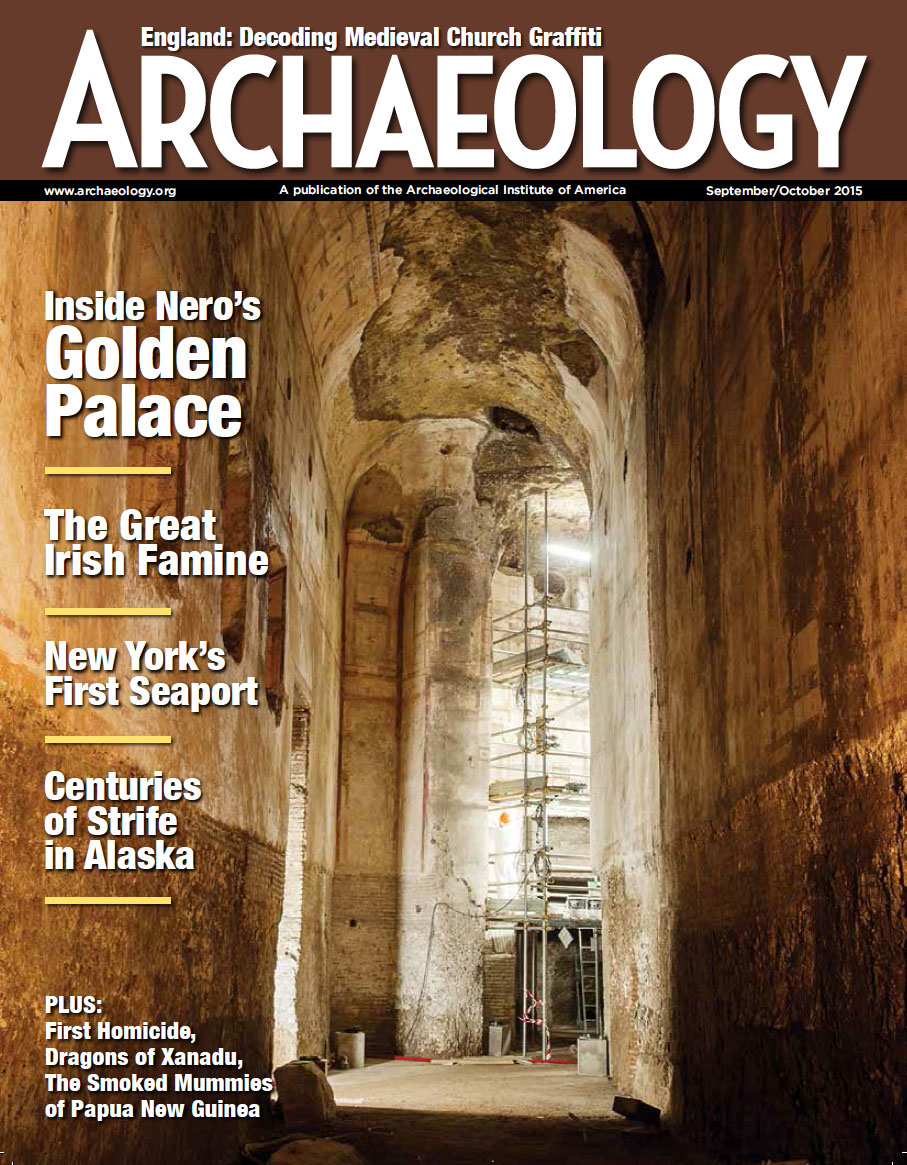

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

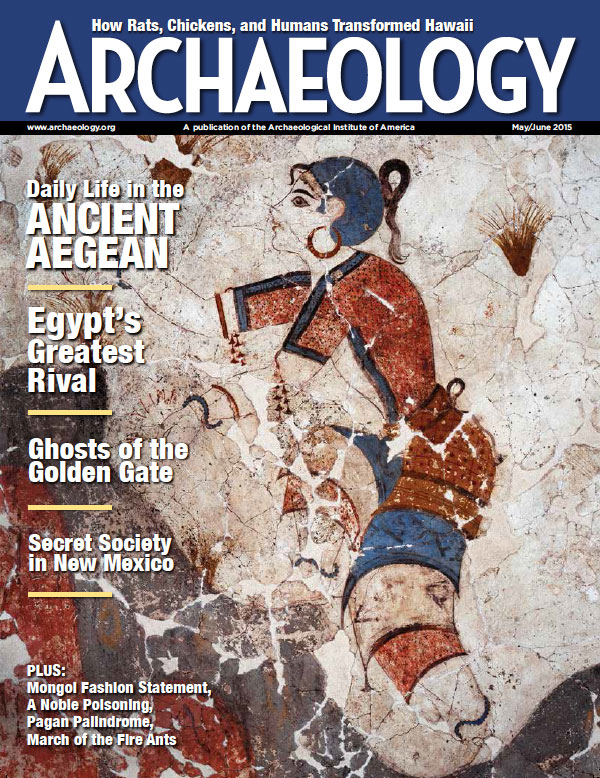

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

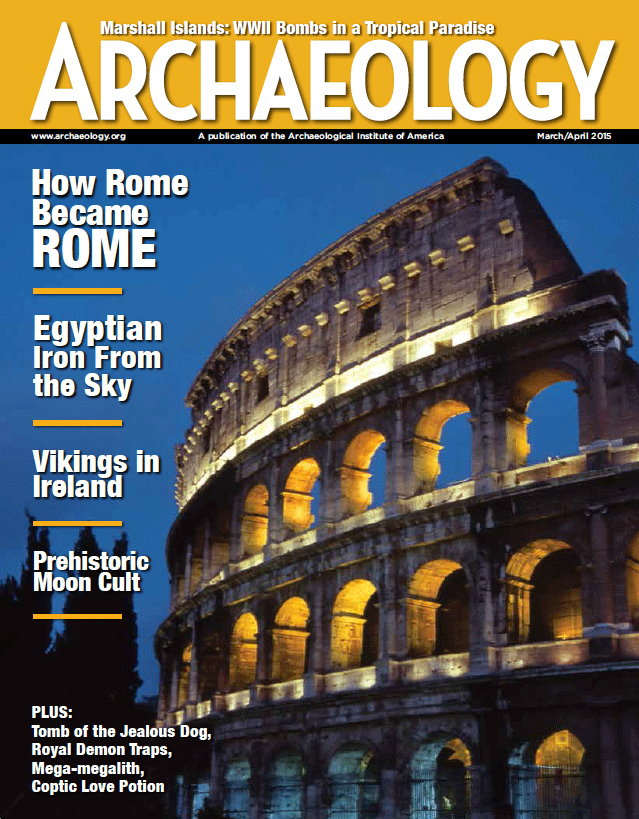

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

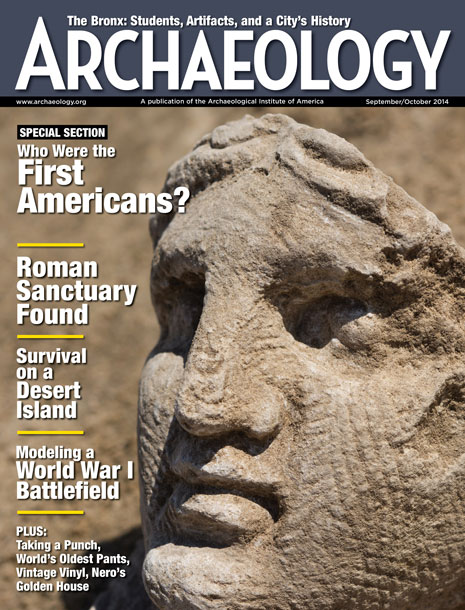

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

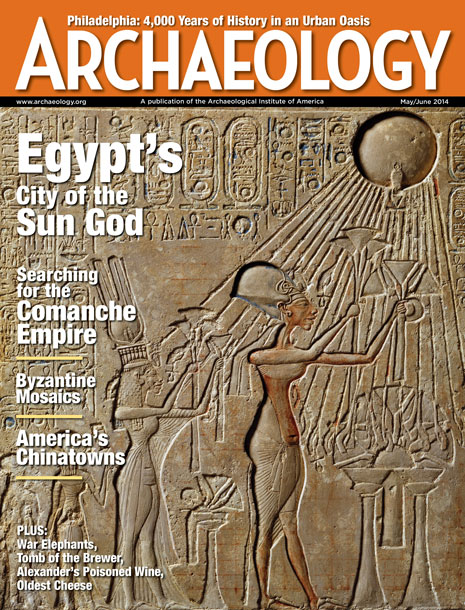

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

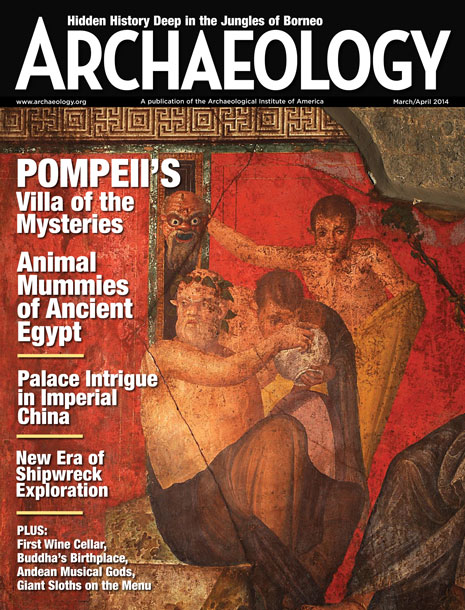

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

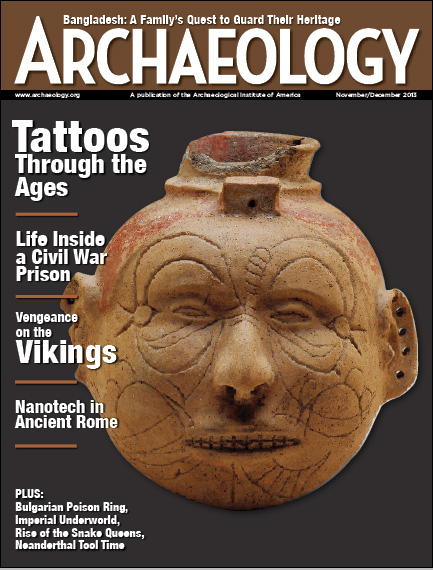

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

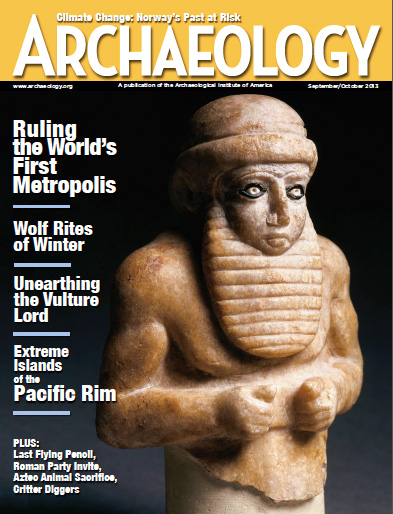

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

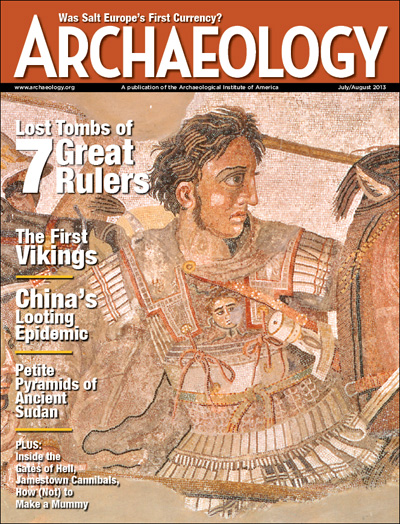

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

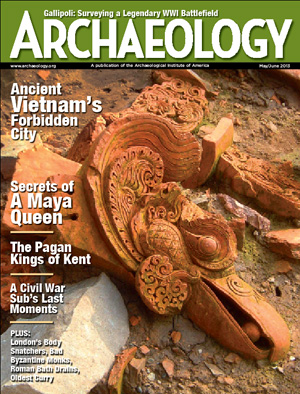

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

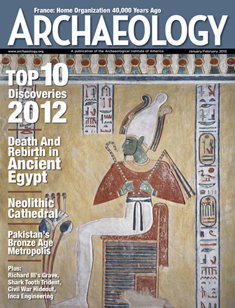

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement