Letter from Bangladesh

A Family's Passion

November/December 2013

One morning in 1933, on his way to school in a small village in eastern India, a teacher named Hanif Pathan happened upon a group of construction workers who, while doing some foundation work on a house, had discovered a terracotta pot containing a cache of silver coins. In the days and weeks that followed, Pathan started to look for more coins in a three-mile radius around his village, Bateshwar, in what is now Bangladesh, roughly 40 miles northeast of the capital, Dhaka.

He discovered that the best time to search was after the monsoon season would erode low-lying soil, and he continually came across semiprecious stones and scattered potsherds with intricate designs, simply sticking out of the ground. He learned that other villagers were also finding gems, which they had taken to calling Solaimani pathor, or “stones of the Sulaiman,” the Islamic prophet who wore an onyx pendant to ward off evil.

Pathan spent the next three decades traversing the length of Bateshwar and its neighboring village to the north, Wari. He made an inventory of his findings—which included more pots full of coins—and stored them in his house. Trying to attract the attention of international experts, he submitted countless articles about his finds to newspapers. The day in 1955 that the local Daily Azad published one of his articles, Pathan ran to the classroom of his 15-year-old son, Habibulah, to show him the paper. According to Habibulah, now 73, that was the day when he realized he would eventually be carrying on his father’s passion.

“One day, while walking to school in the rain, I found an amethyst bead,” Habibulah told me last year when I visited the archaeological site known today as Wari-Bateshwar. “I felt as if I had hit upon a king’s ransom. I was so elated that I never took my eyes off the ground from that day onwards. I would look for relics and often found a coin or two to bring to my father. As his eyesight and hearing began receding, I acted as his eyes and ears.”

Hanif Pathan passed away in 1989. Today, Habibulah, also a schoolteacher, lives in the same tin-roofed, concrete house he grew up in and looks after a modest museum in its annex. There, artifacts are piled onto shelves that reach seven feet high. Habibulah is actively involved in present-day excavations archaeologists are carrying on about a five-minute drive from his home.

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

From the Trenches

An Imperial Underworld

Off the Grid

Splendid Surprise

Neanderthal Tool Time

Dutchman Out of His Depth

Catching a Ride from Ireland

The Snake King's New Vassal

Spying the Past from the Sky

Byzantine Riches

The Neolithic Palate

Secrets of Life in the Soil

Who Was First to the Faroes?

Drones Enter the Archaeologist's Toolkit

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

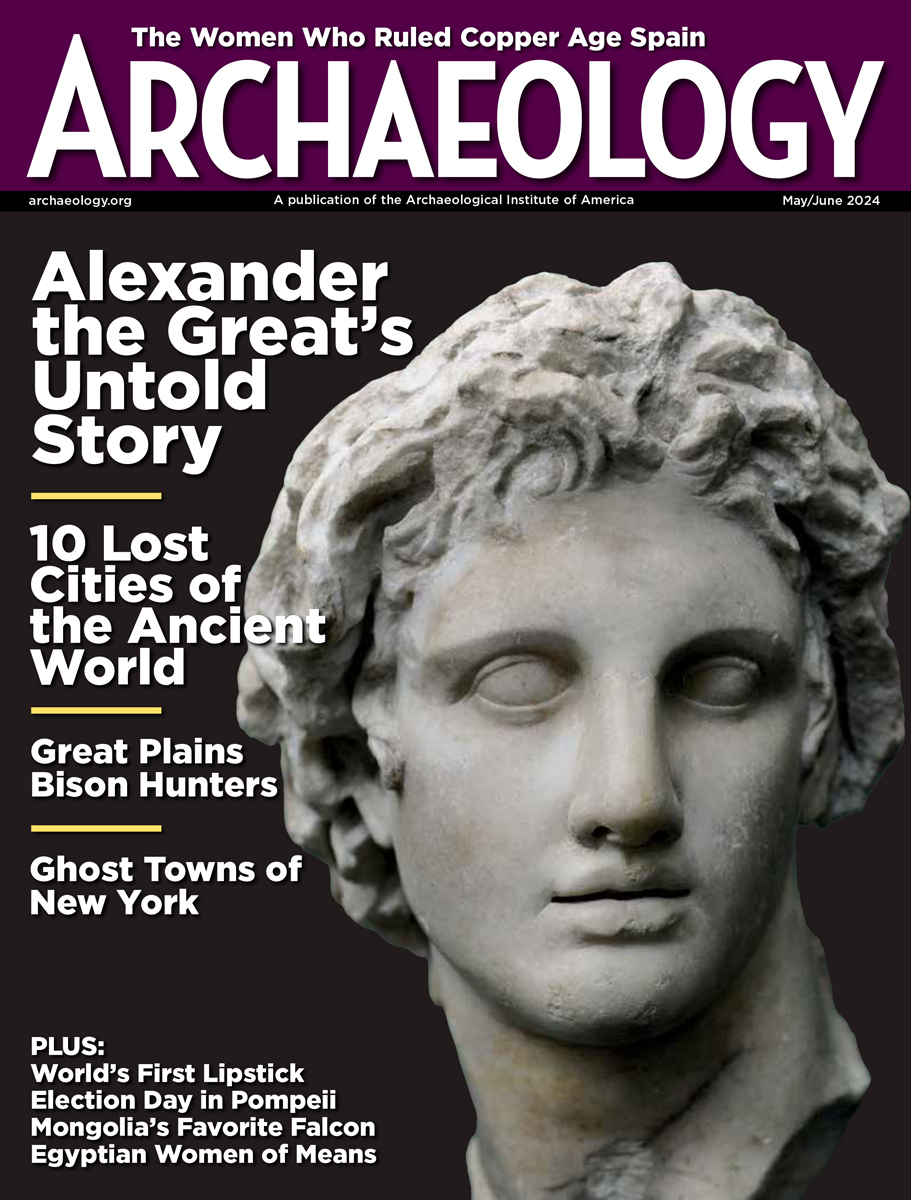

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

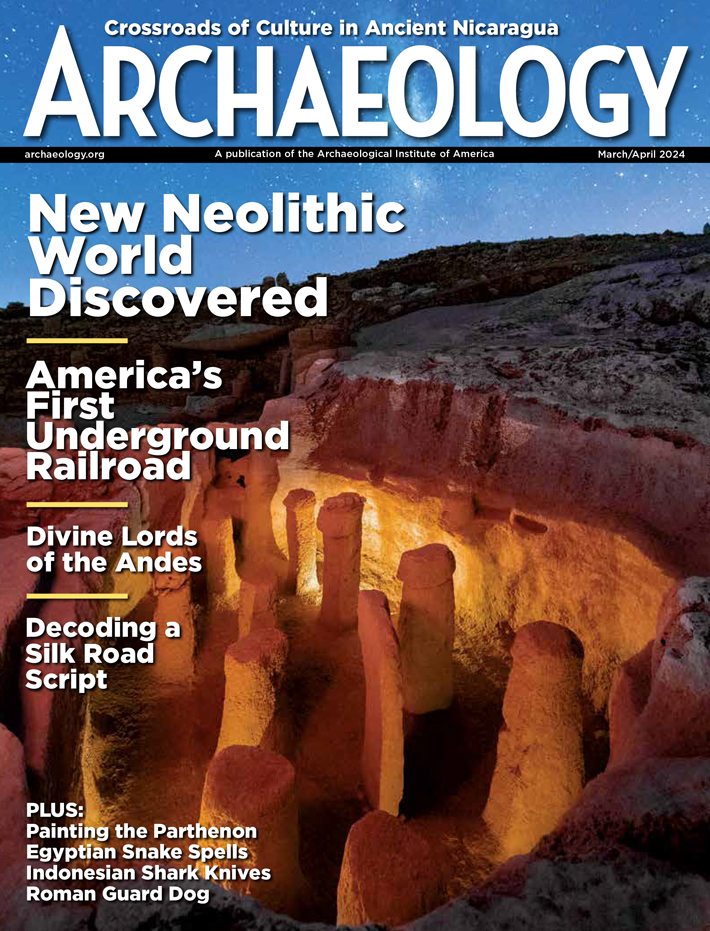

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

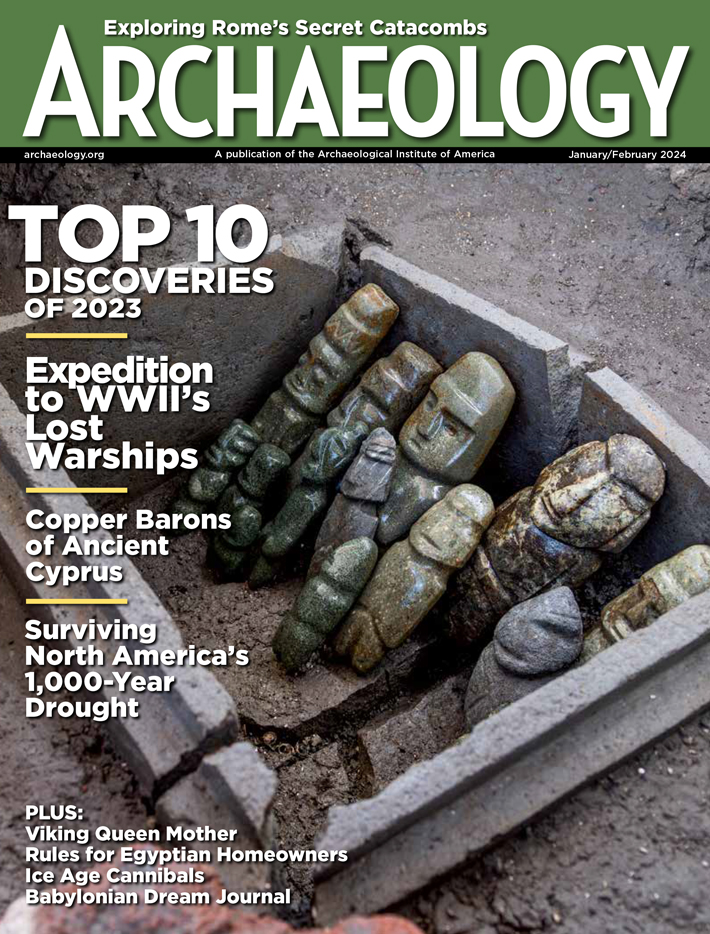

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

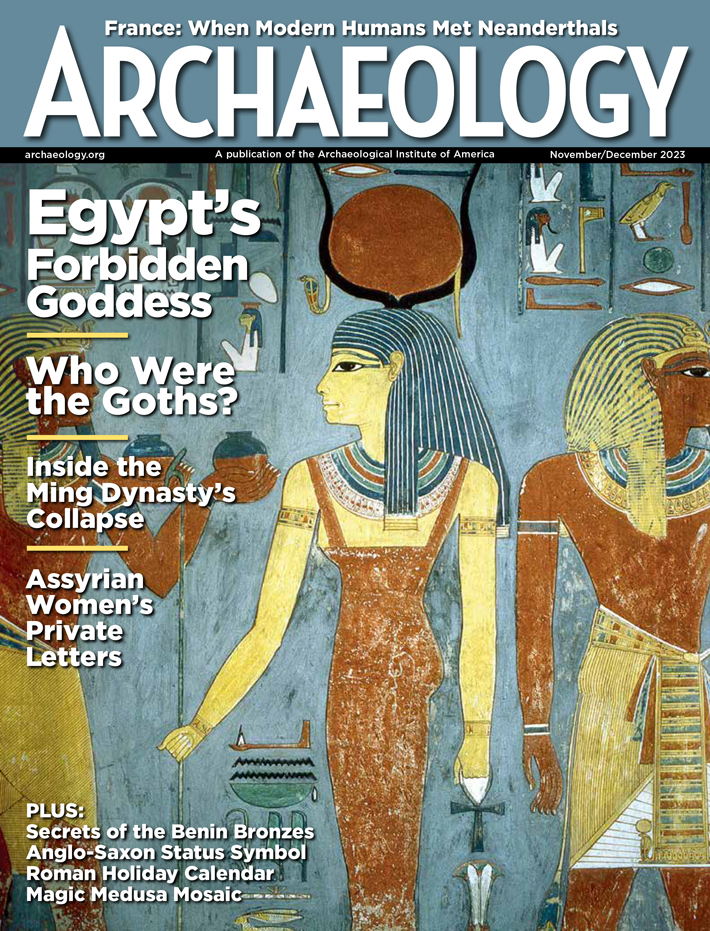

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

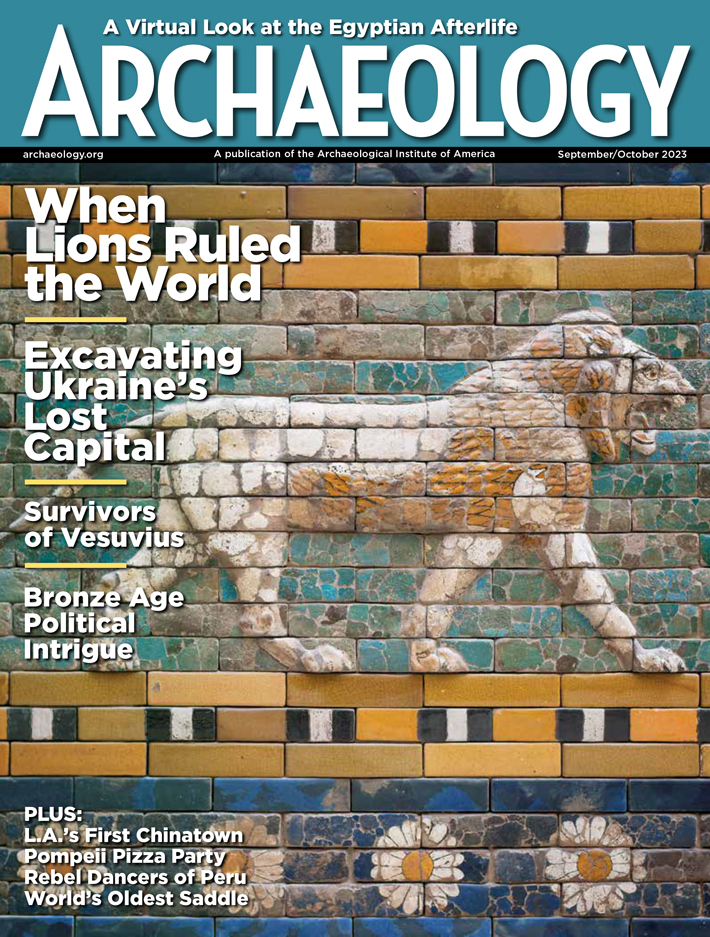

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

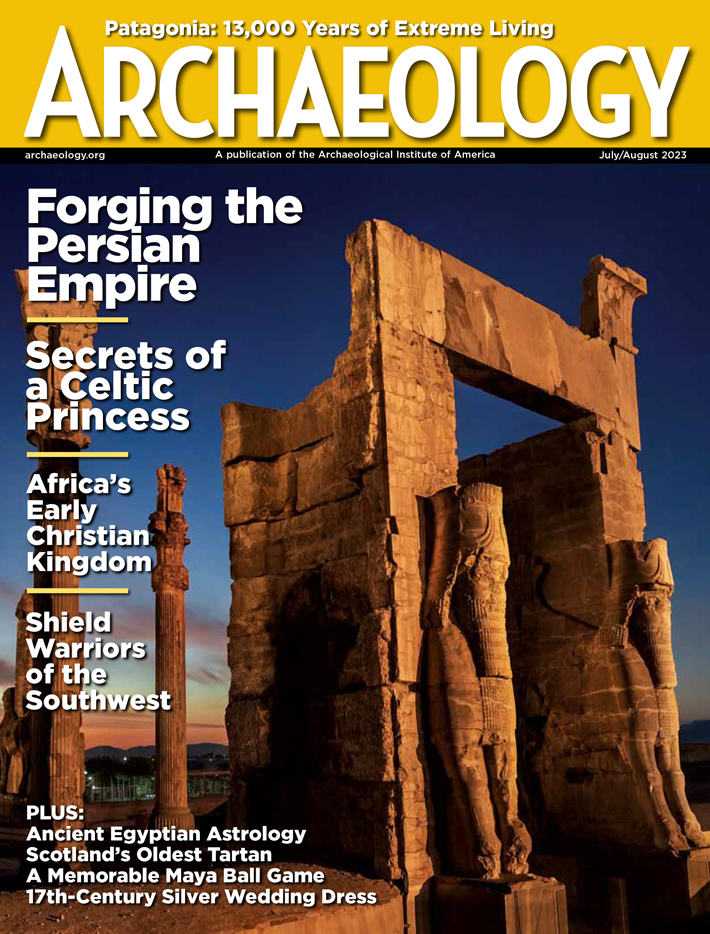

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

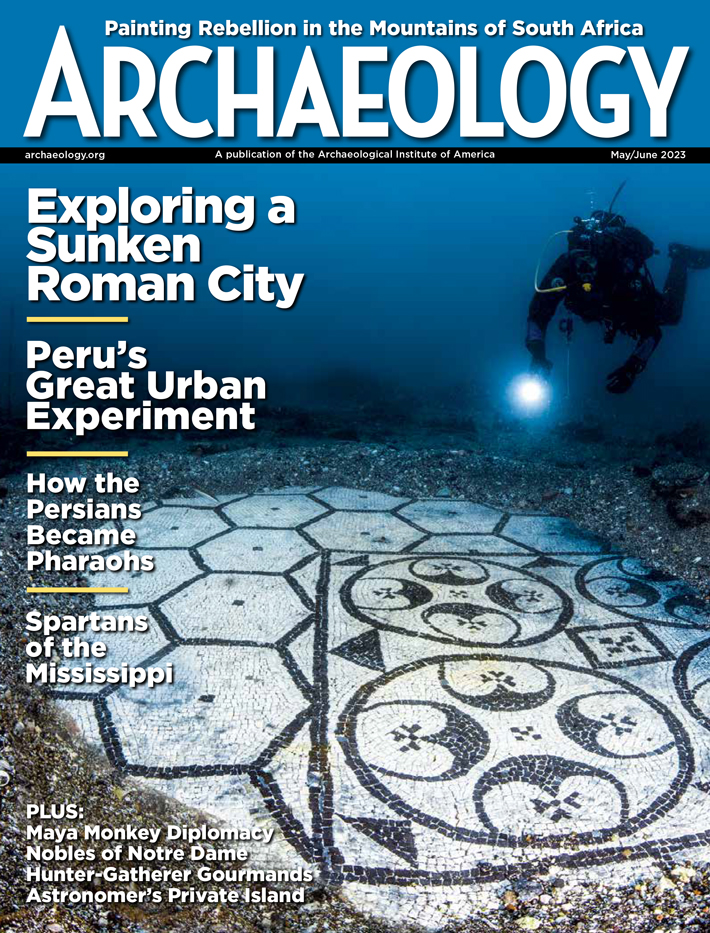

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

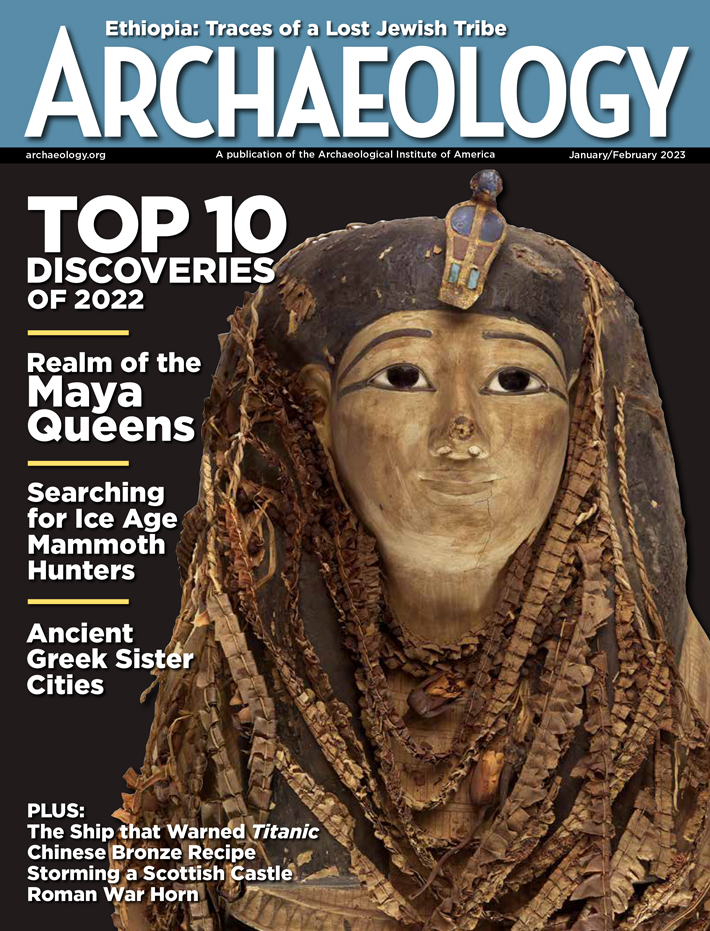

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

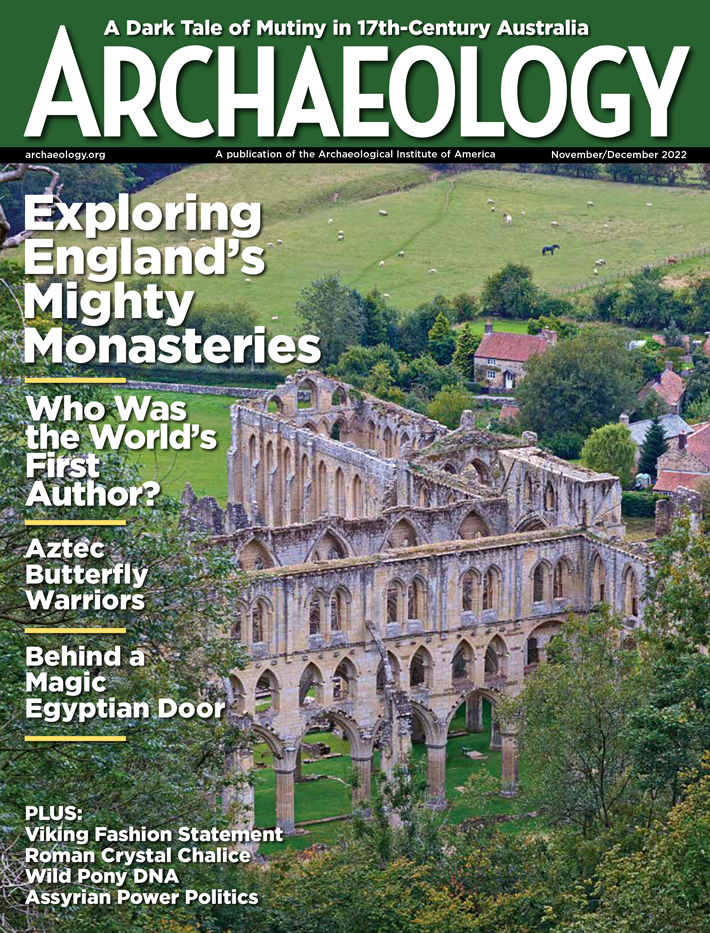

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

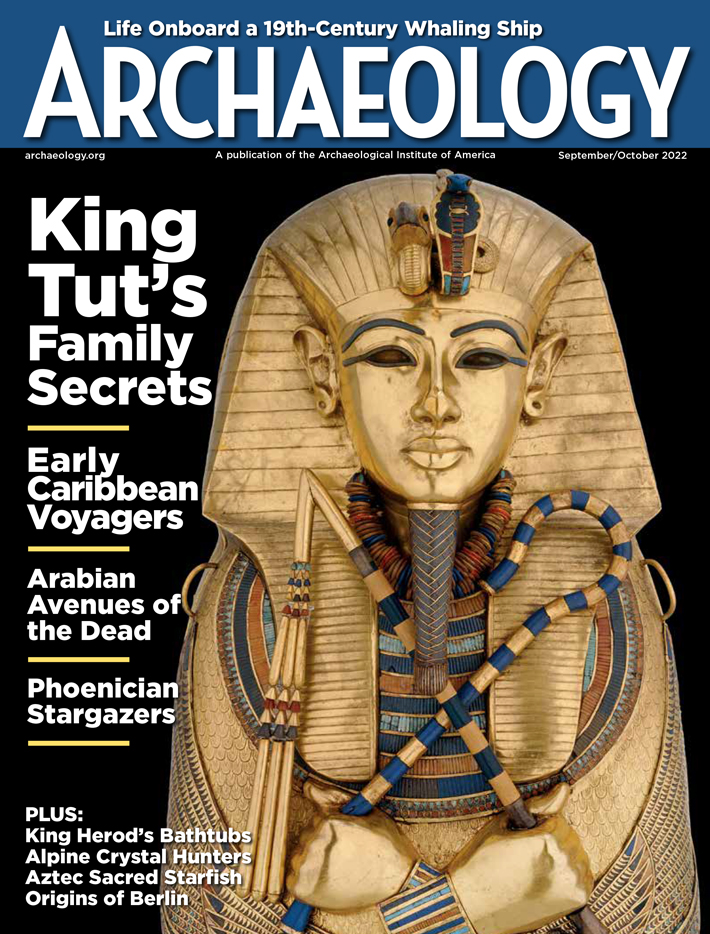

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

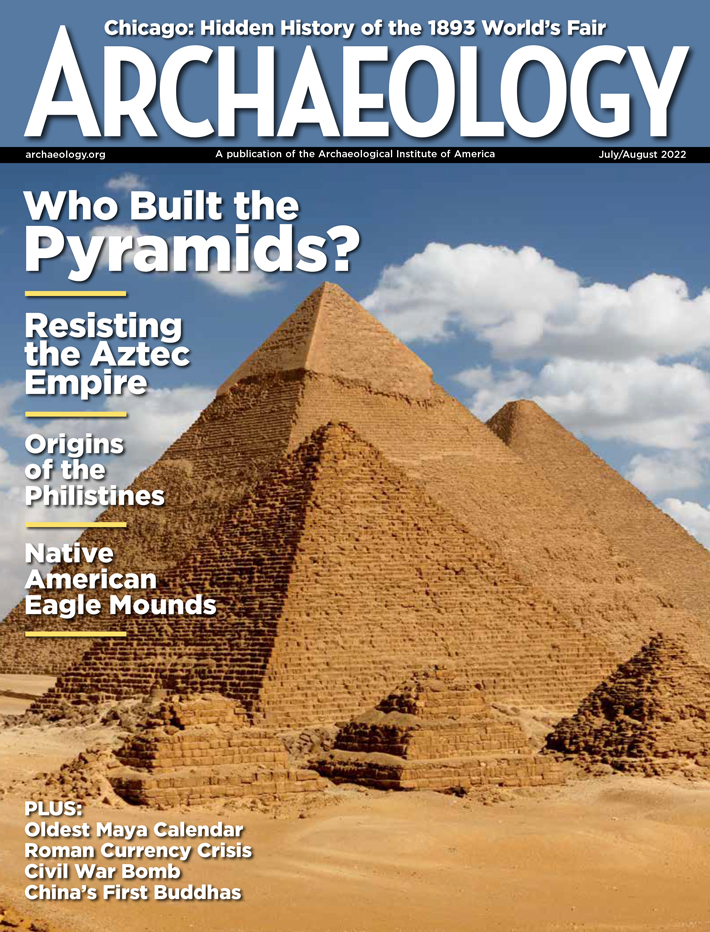

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

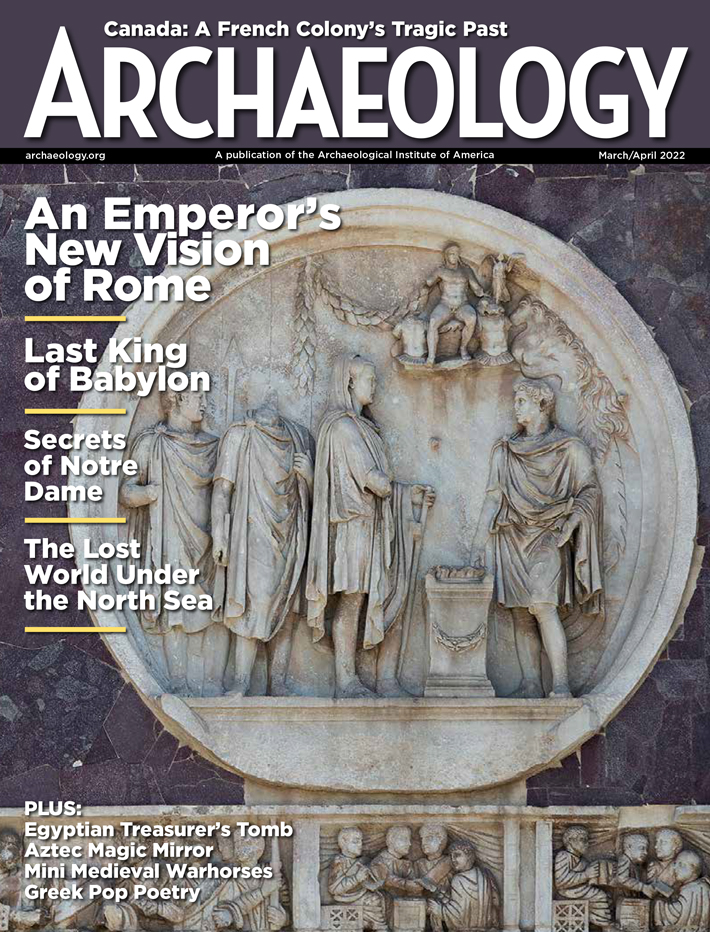

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

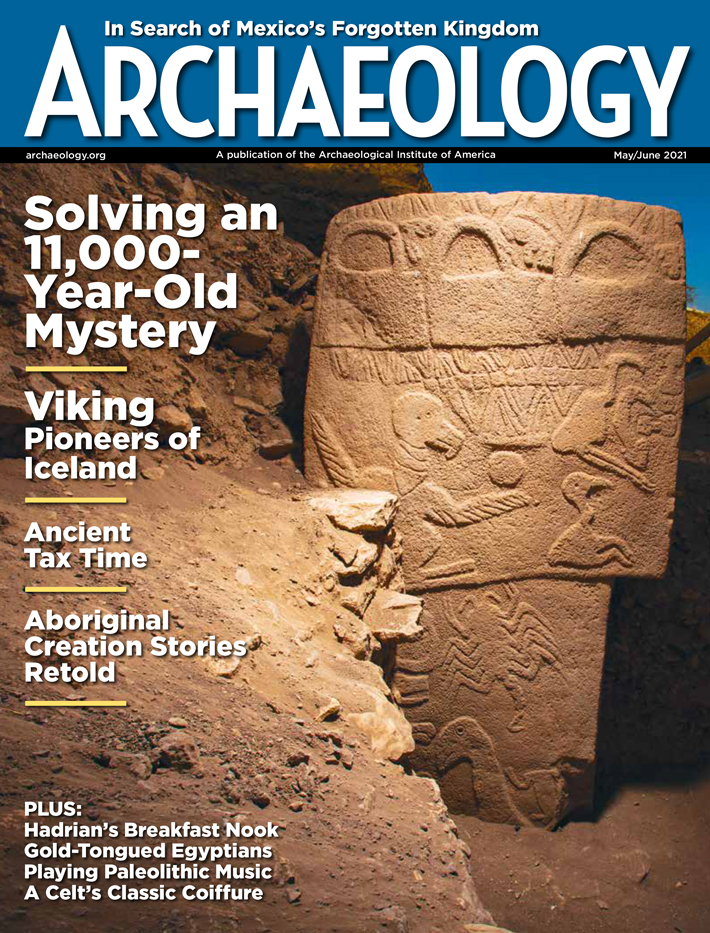

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

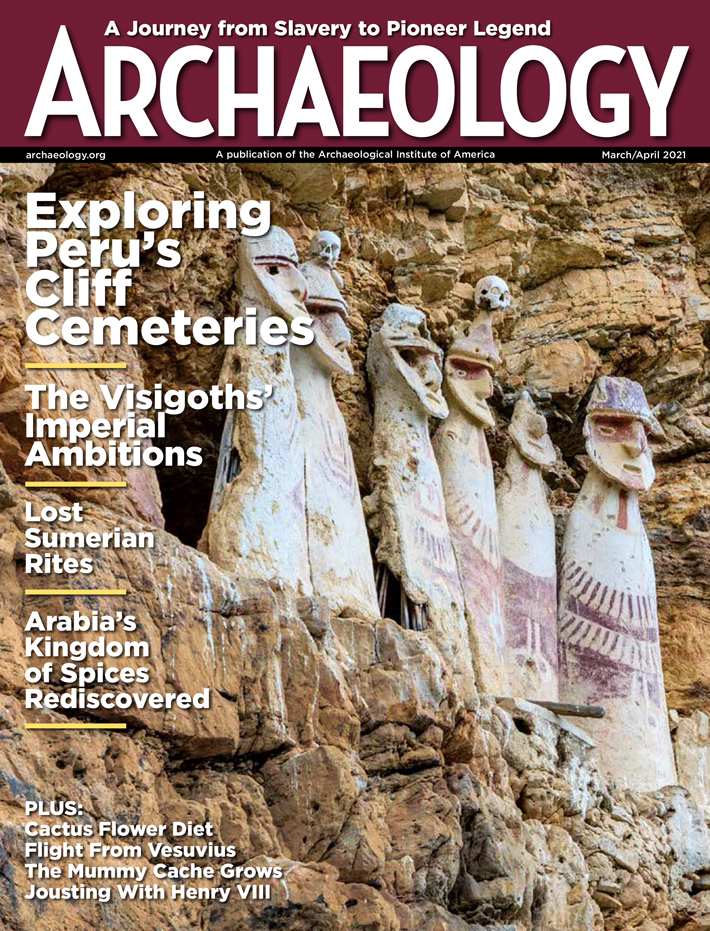

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

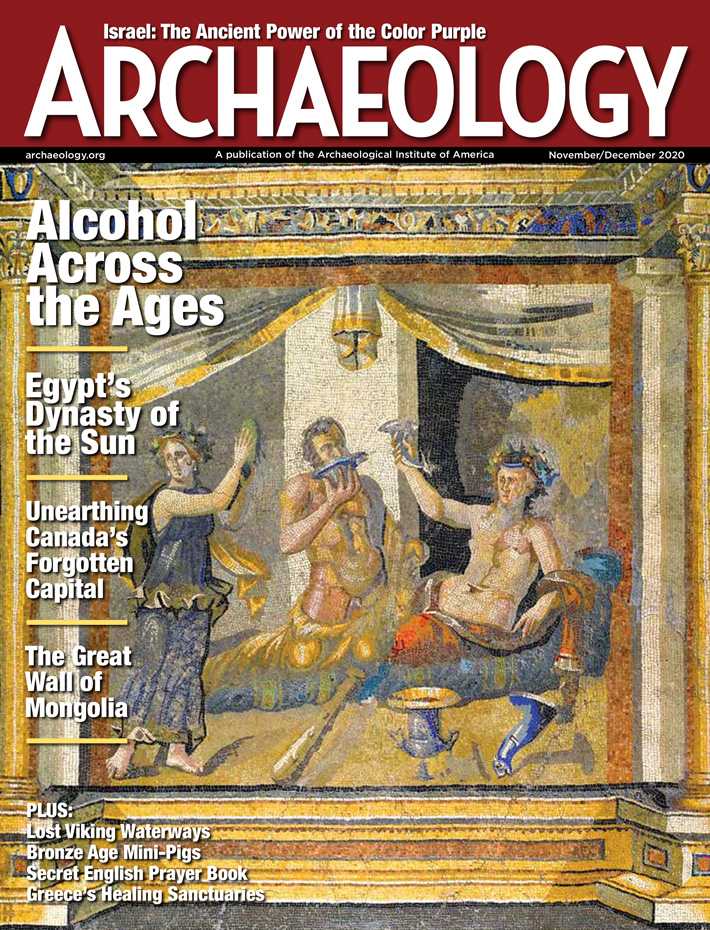

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

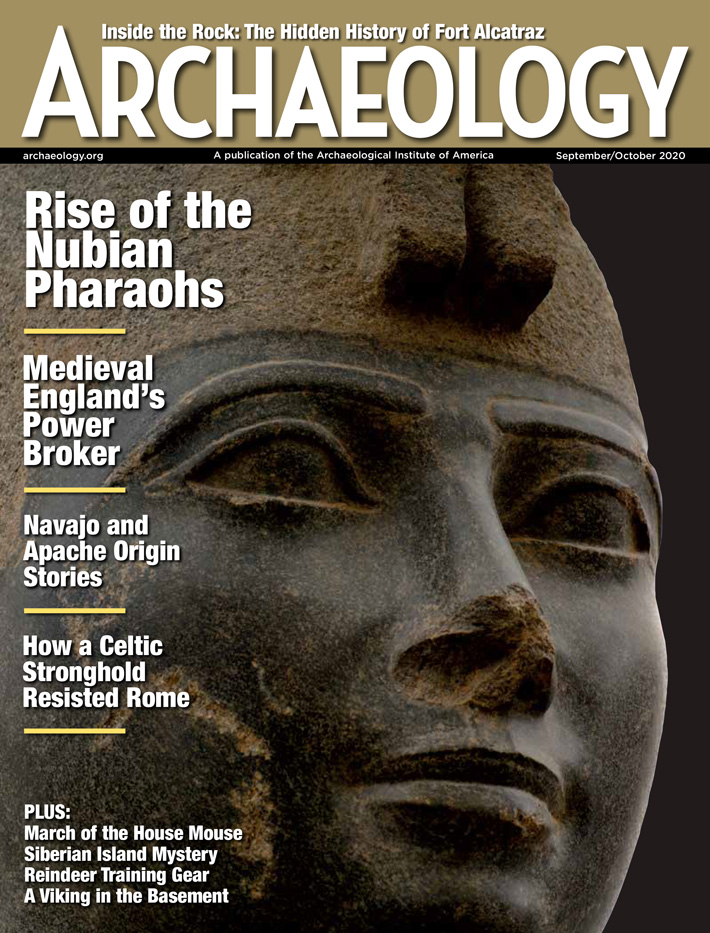

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

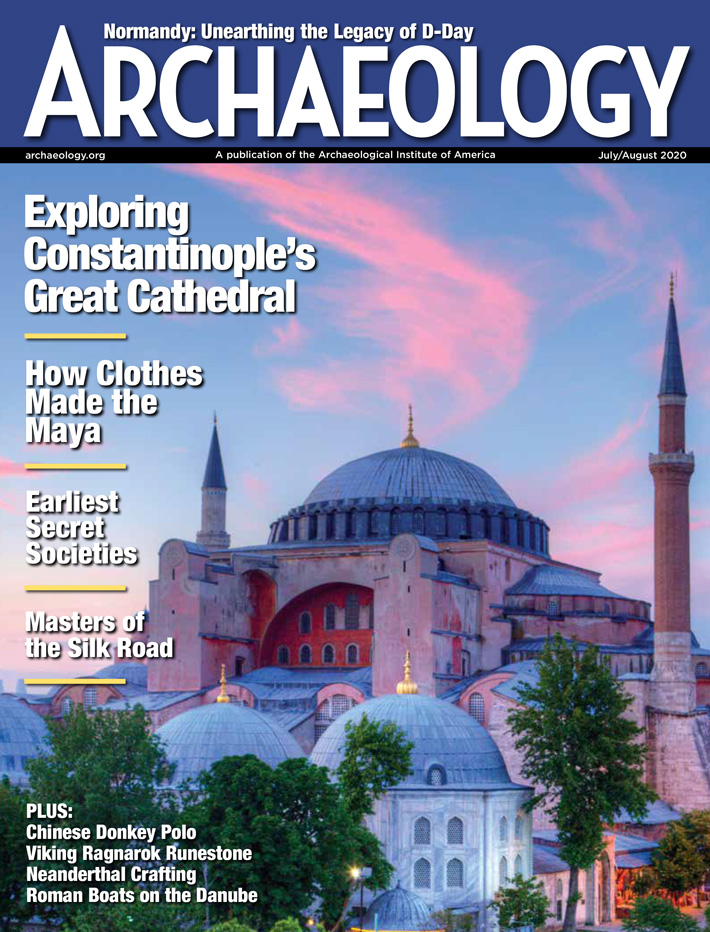

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

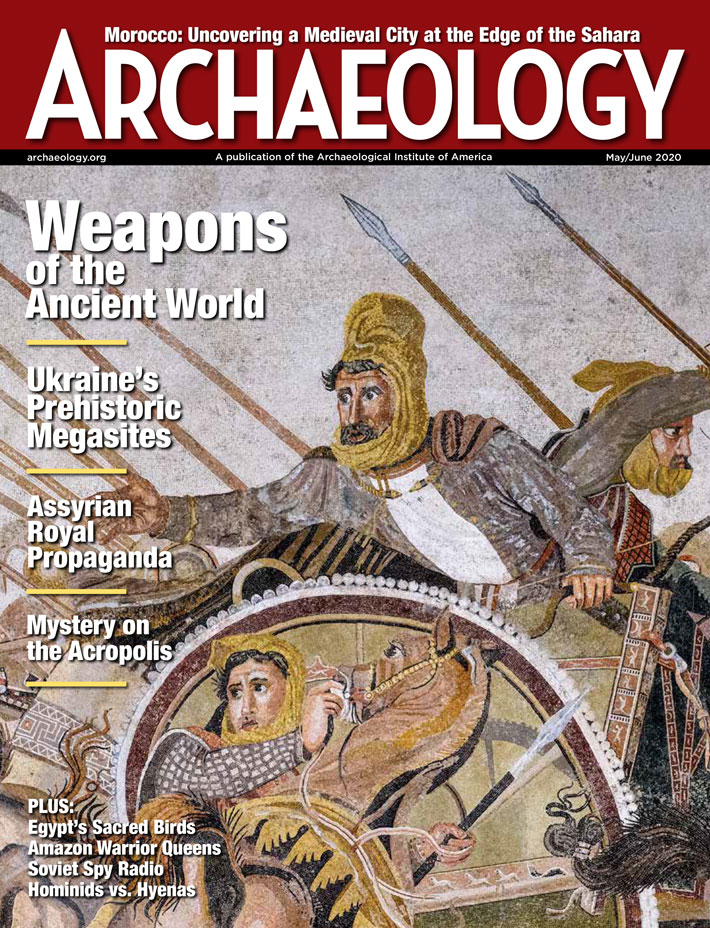

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

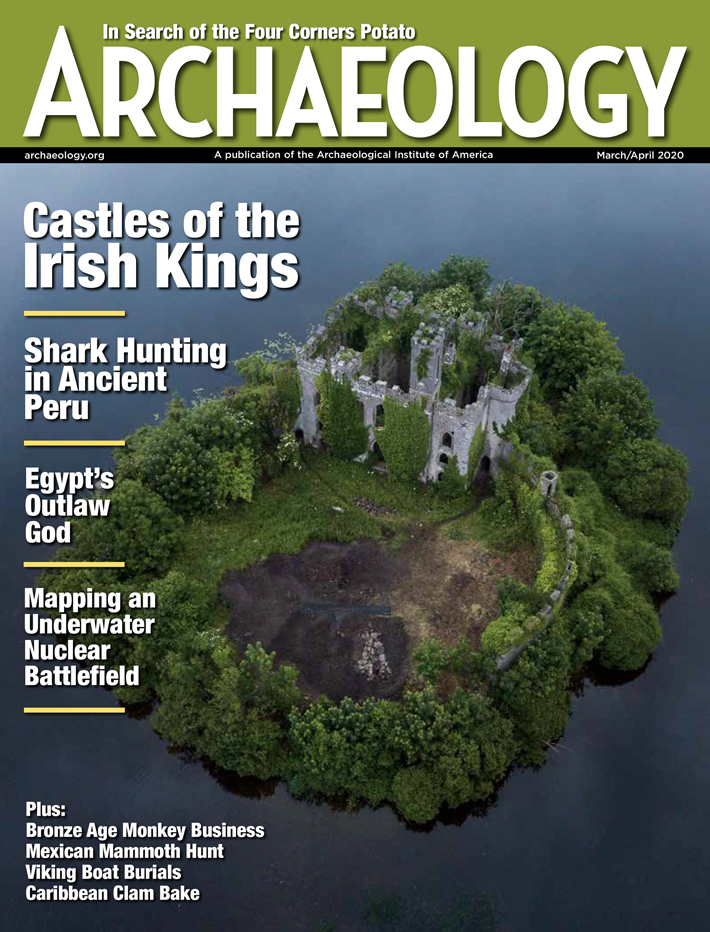

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

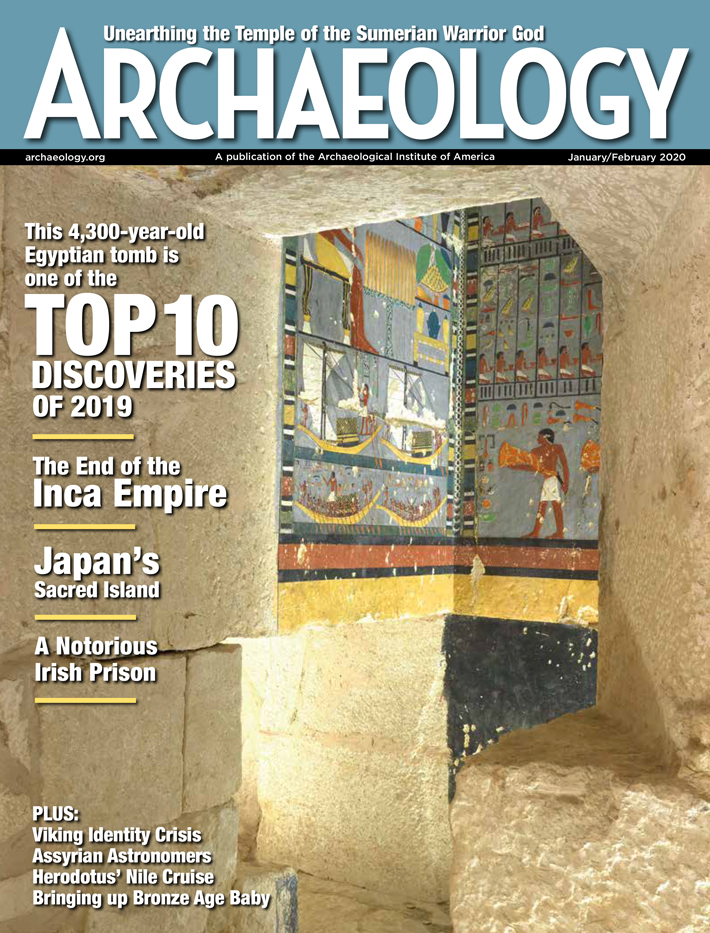

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

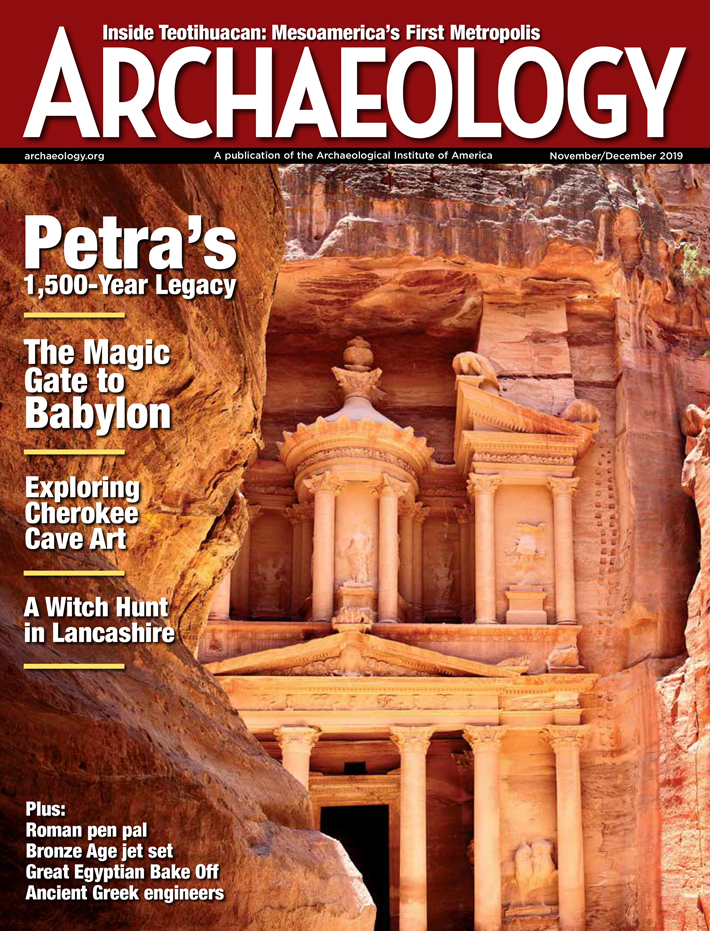

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

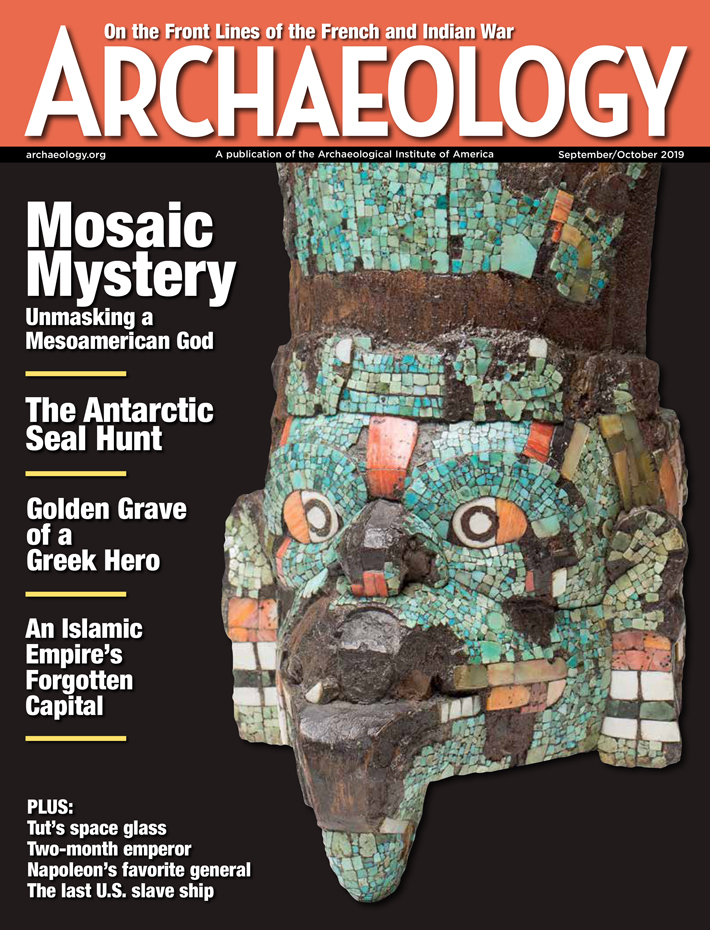

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

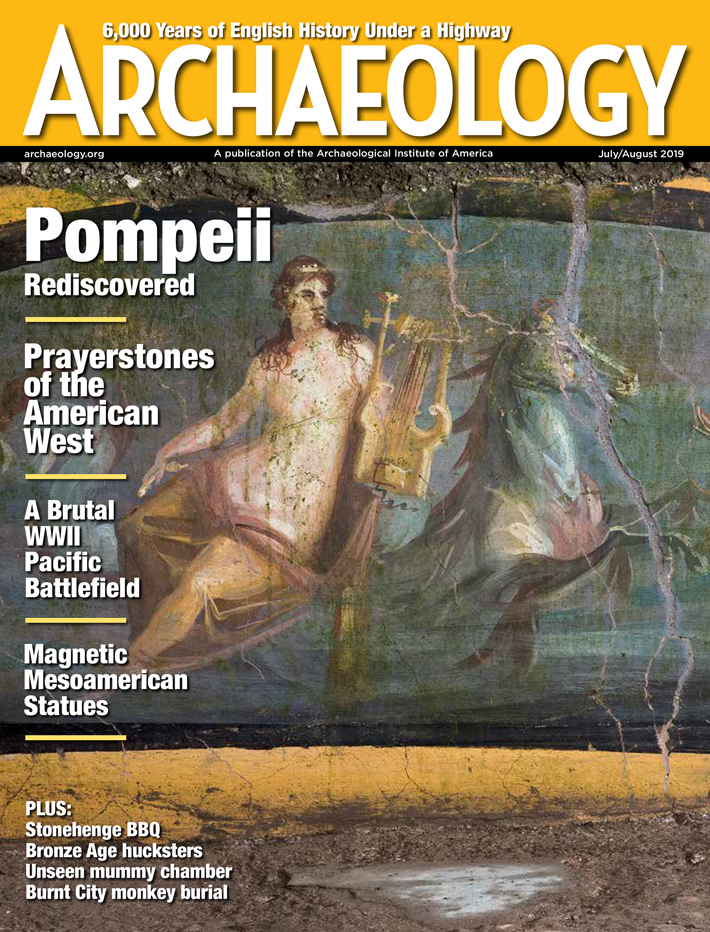

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

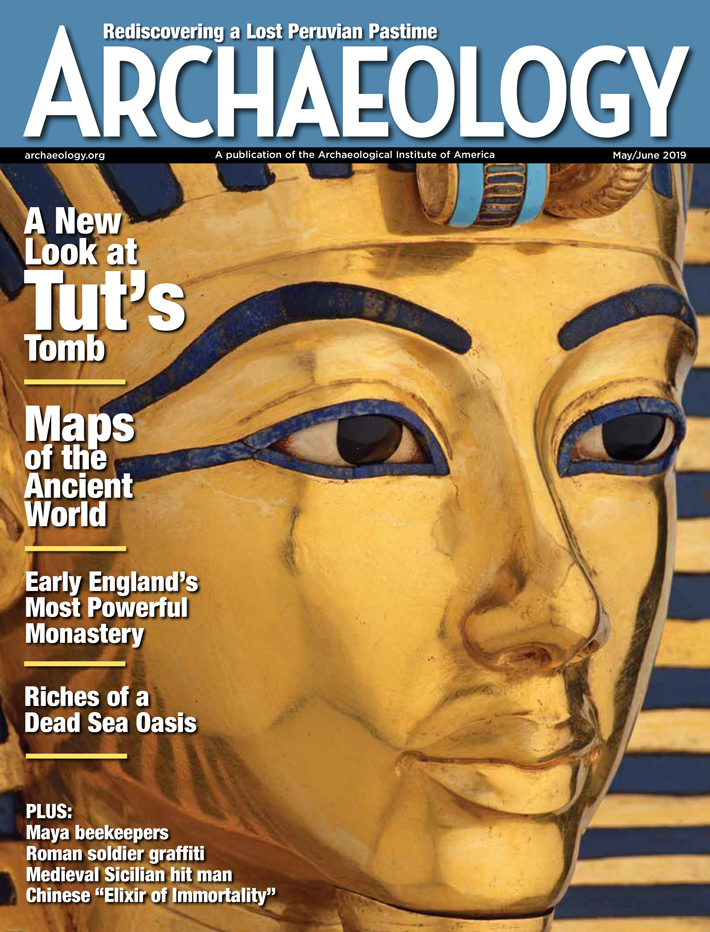

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

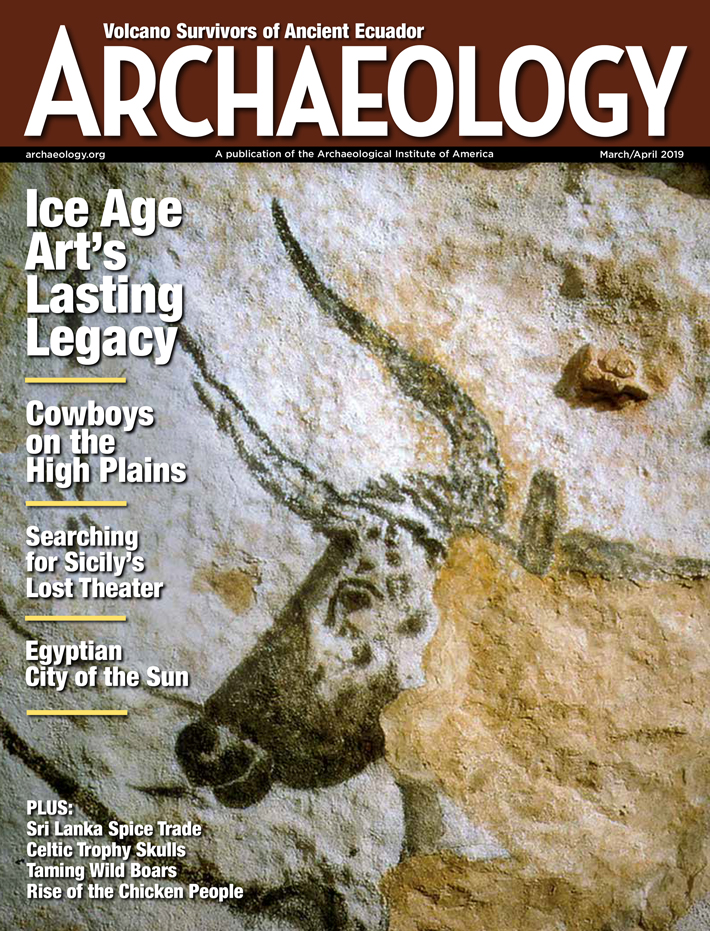

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

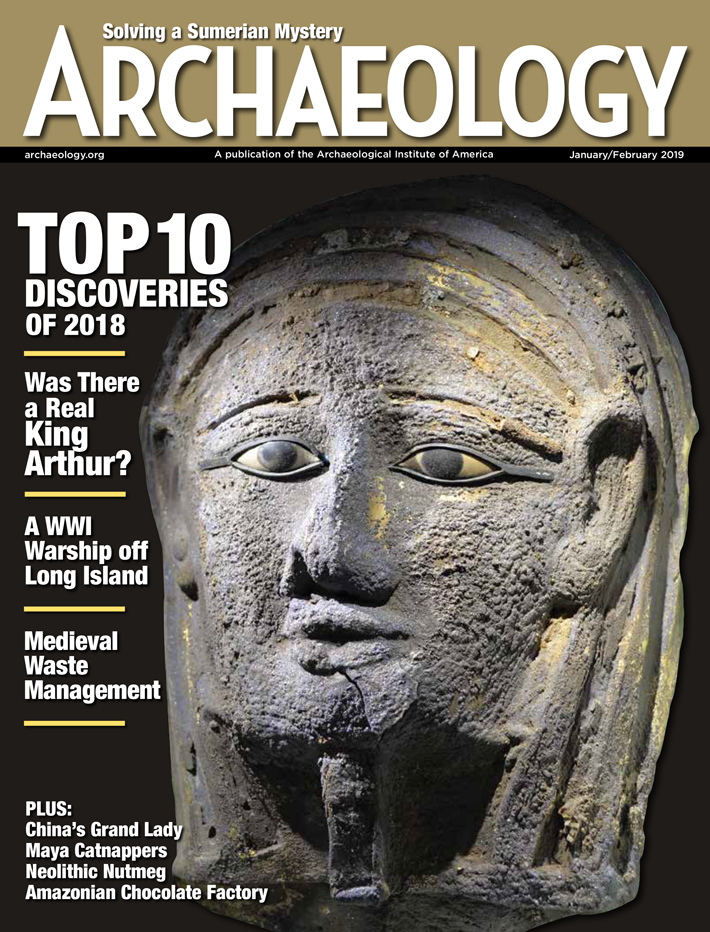

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

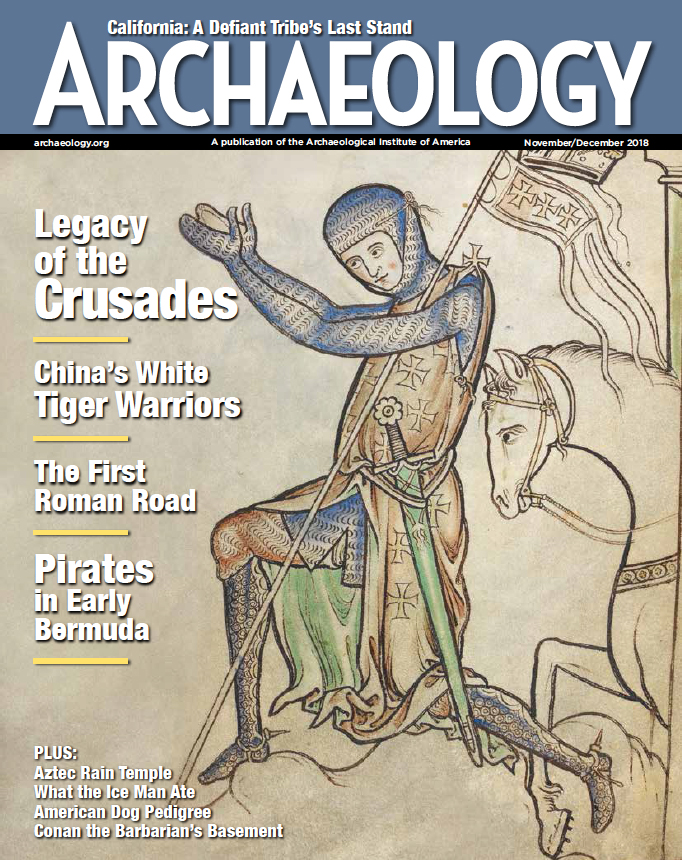

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

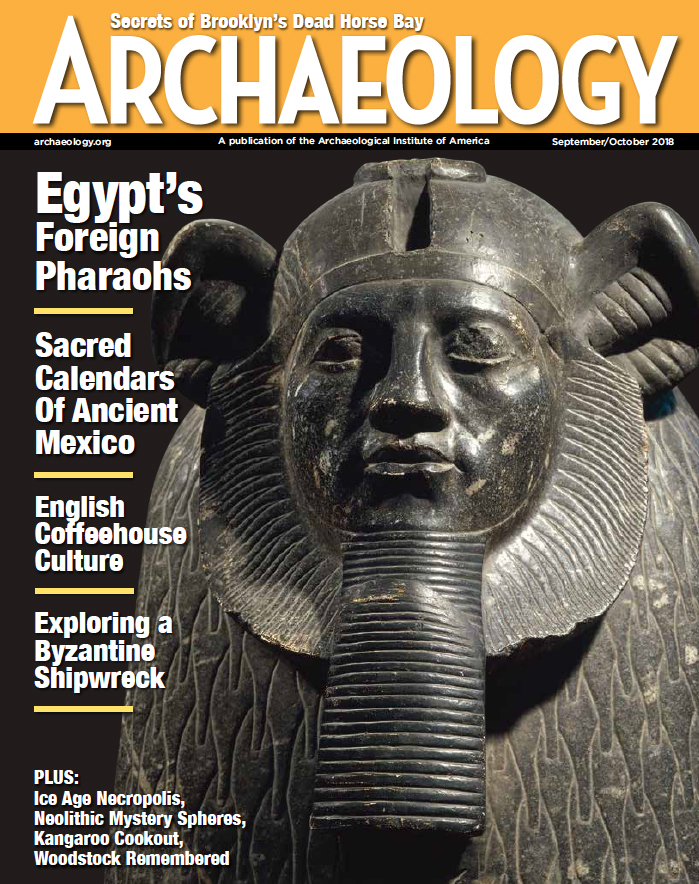

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

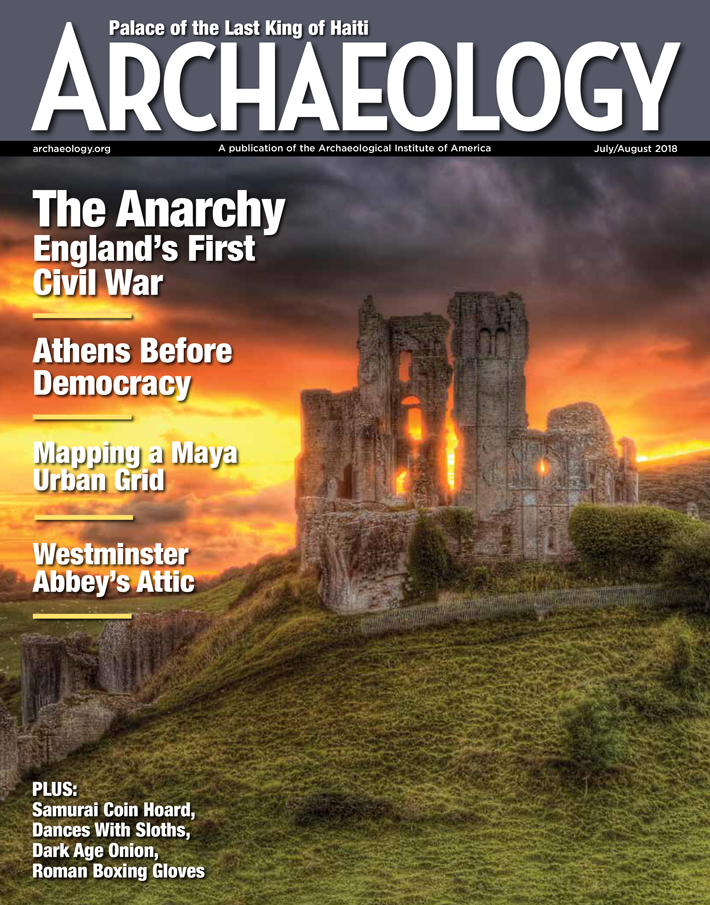

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

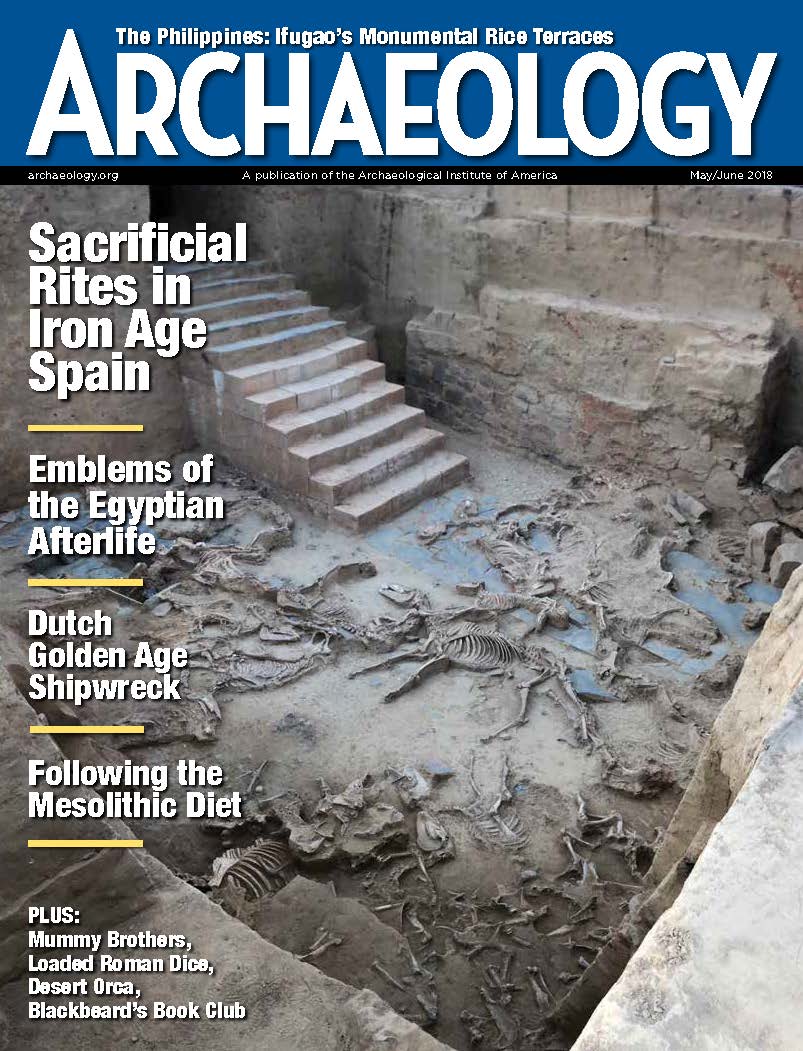

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

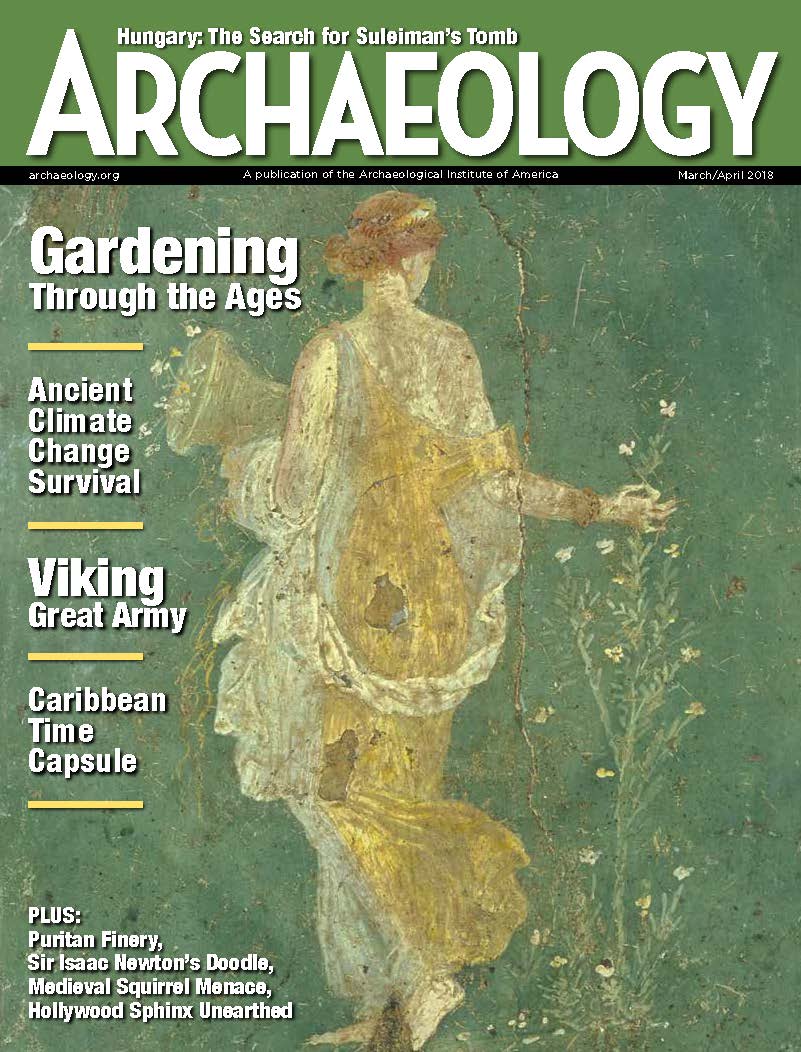

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

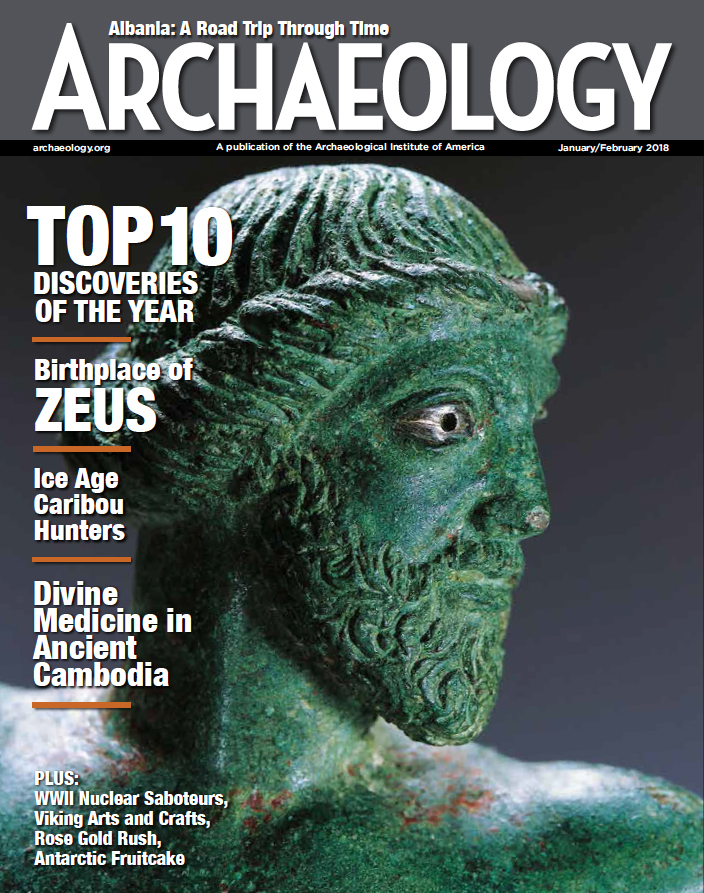

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

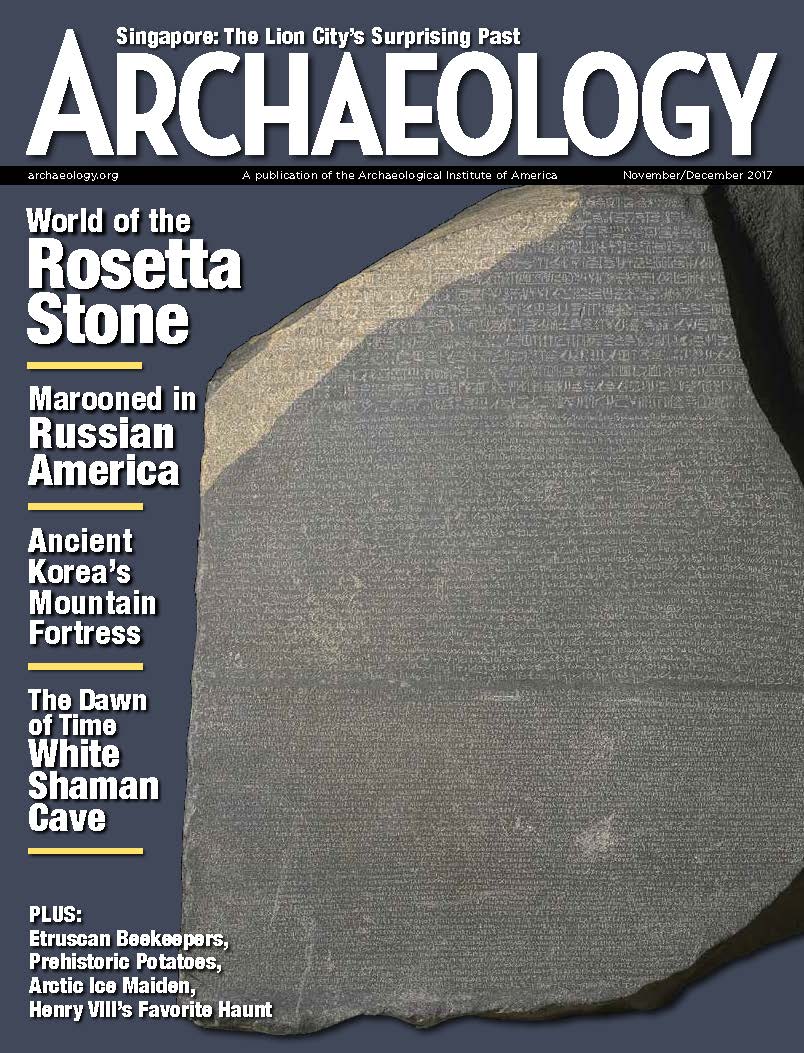

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

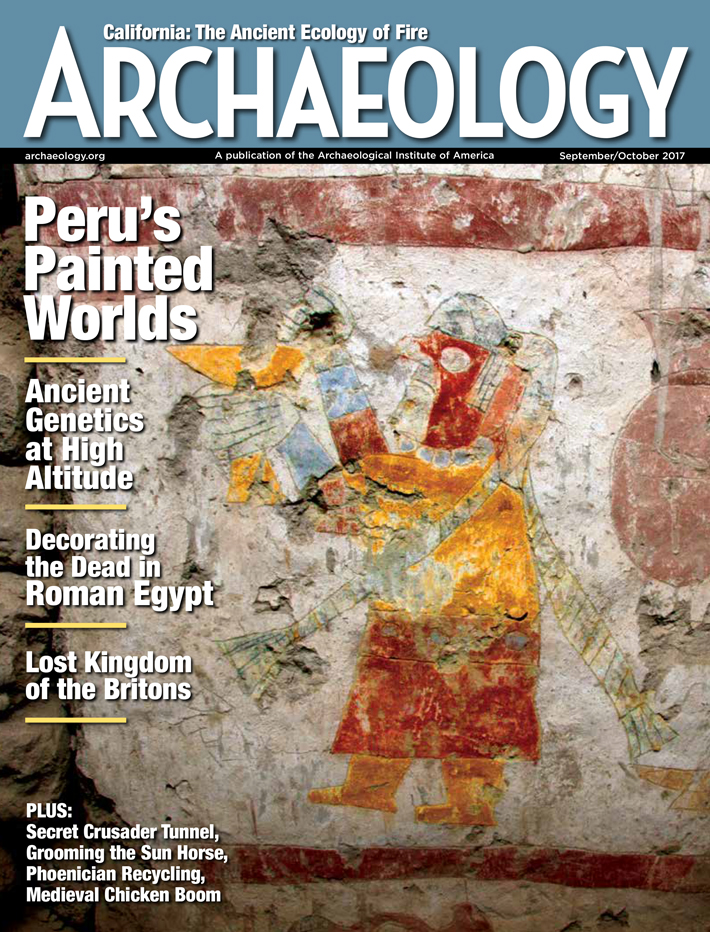

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

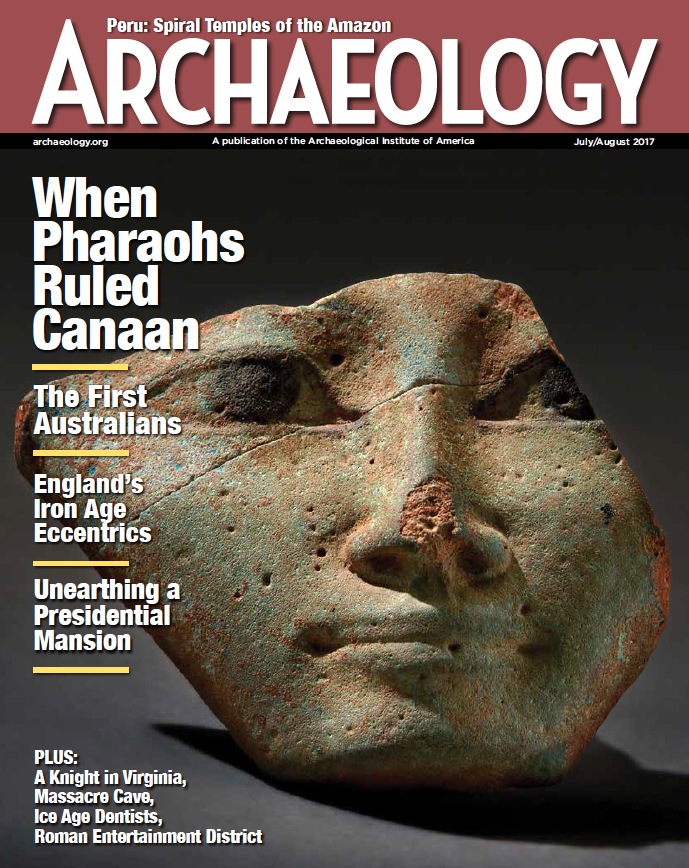

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

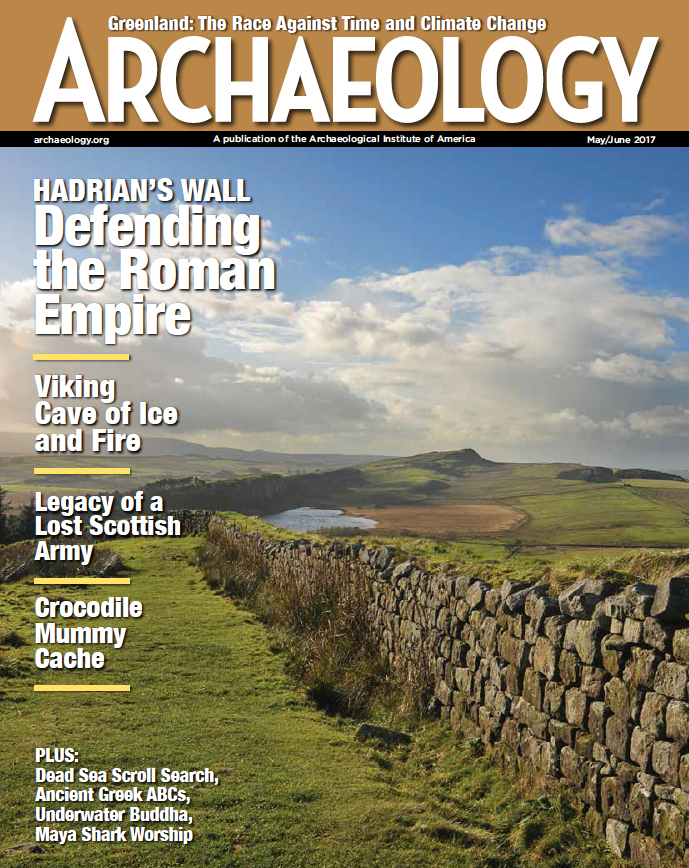

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

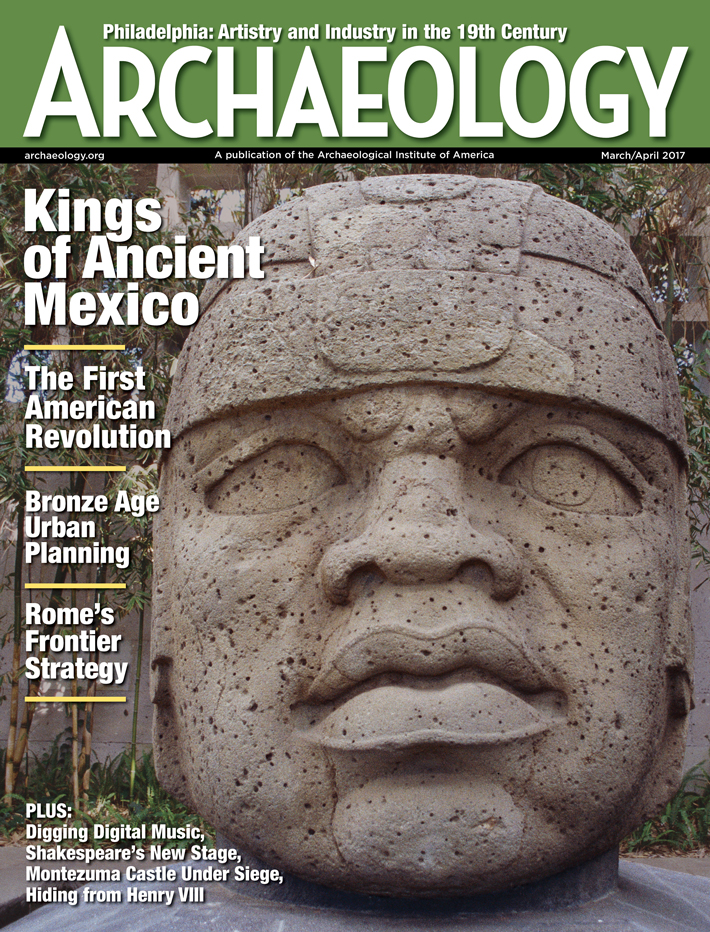

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

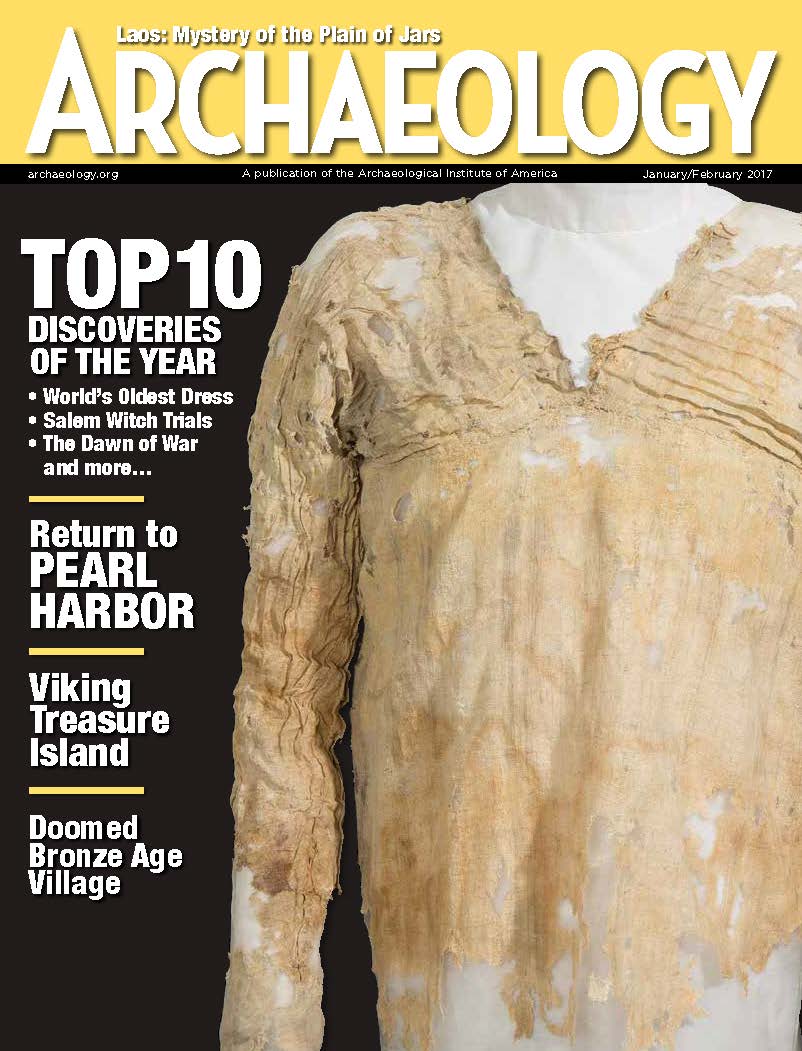

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

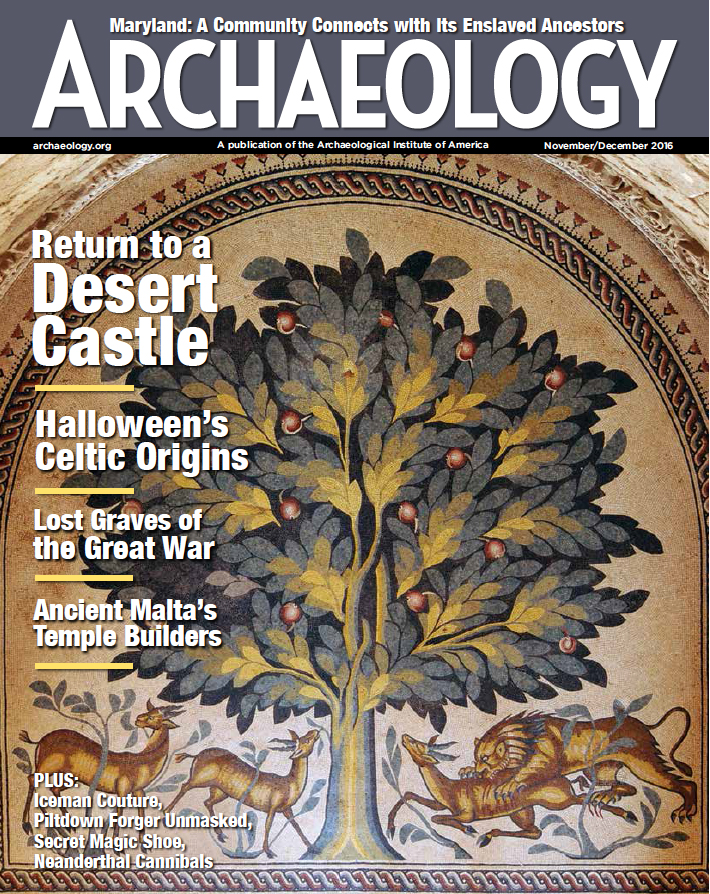

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

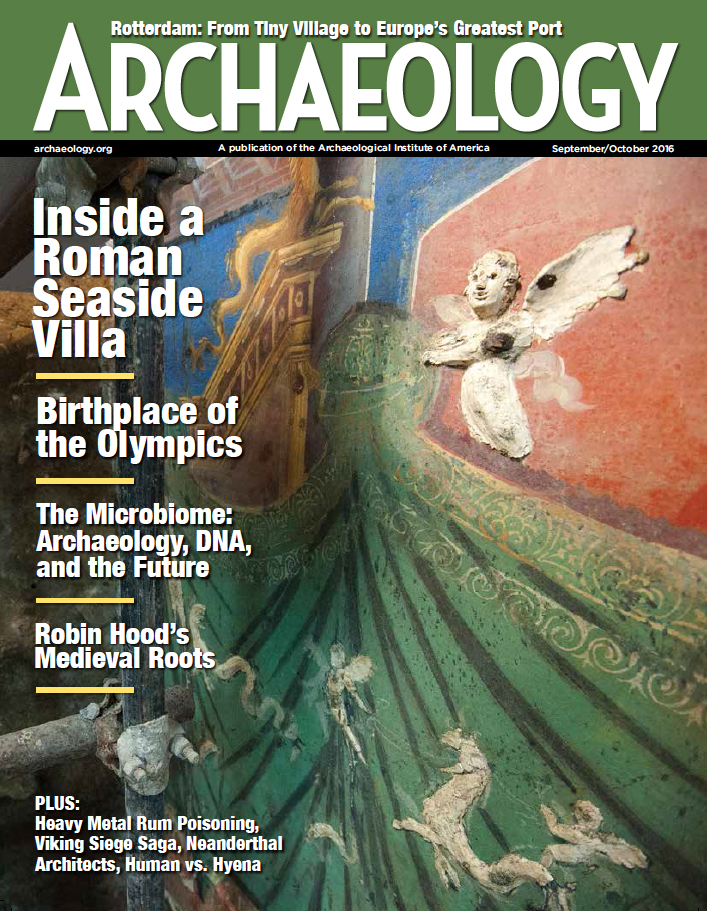

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

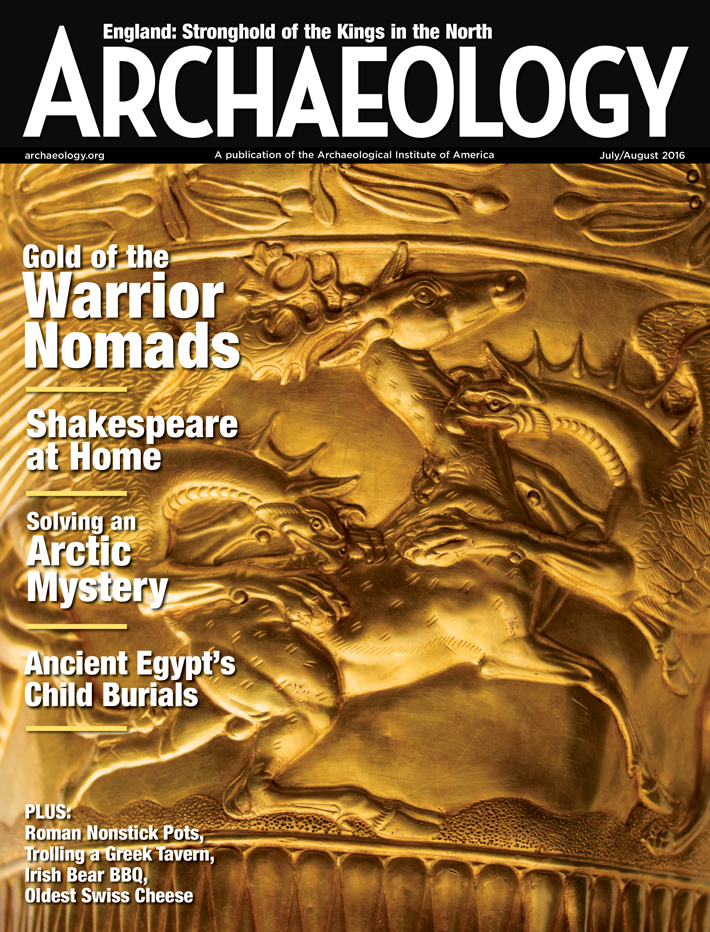

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

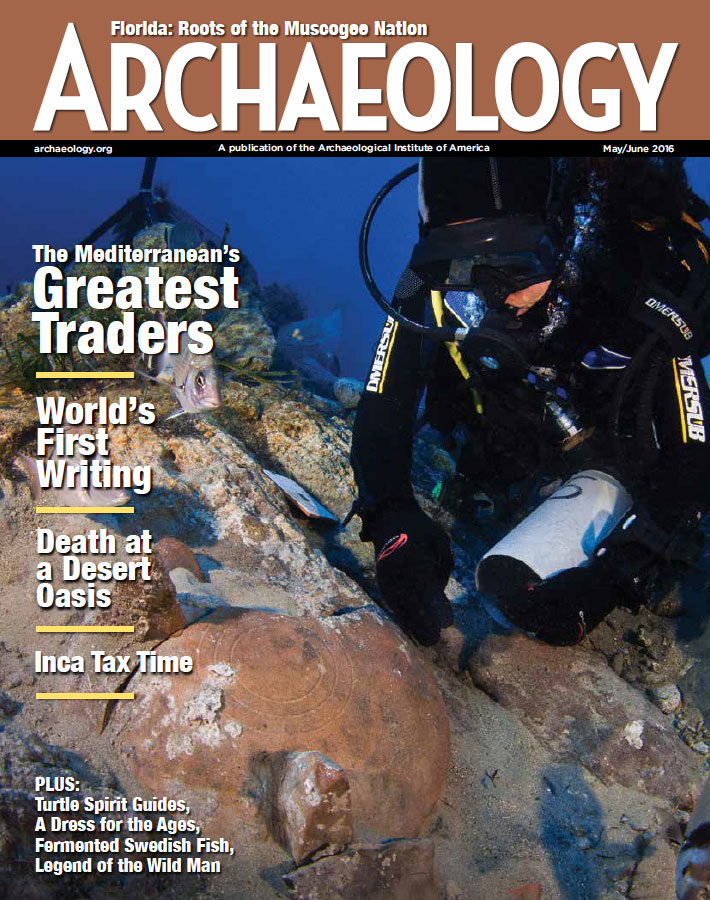

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

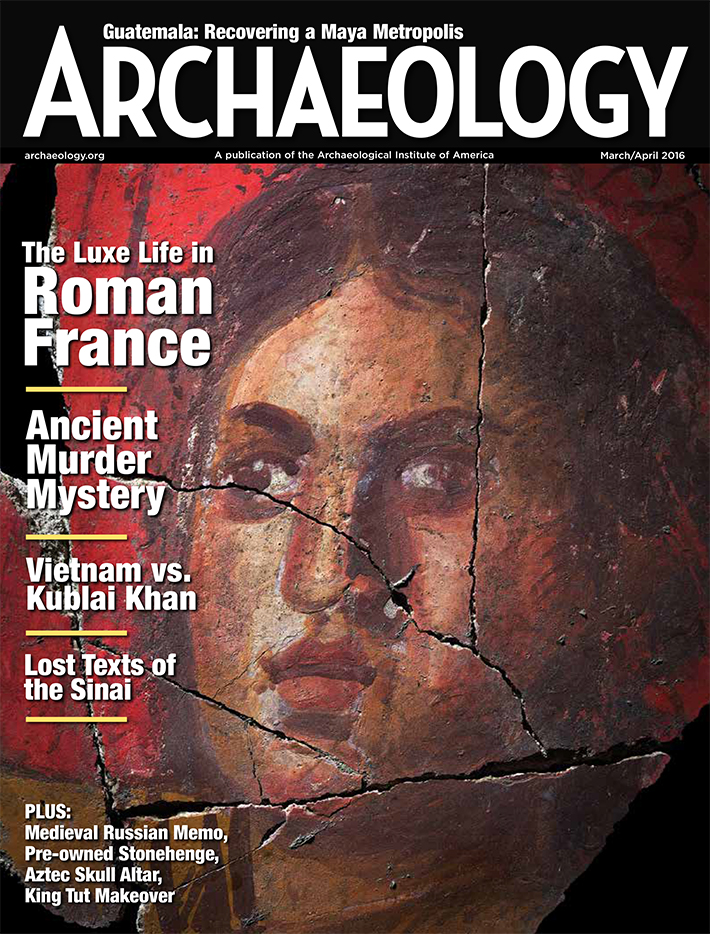

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

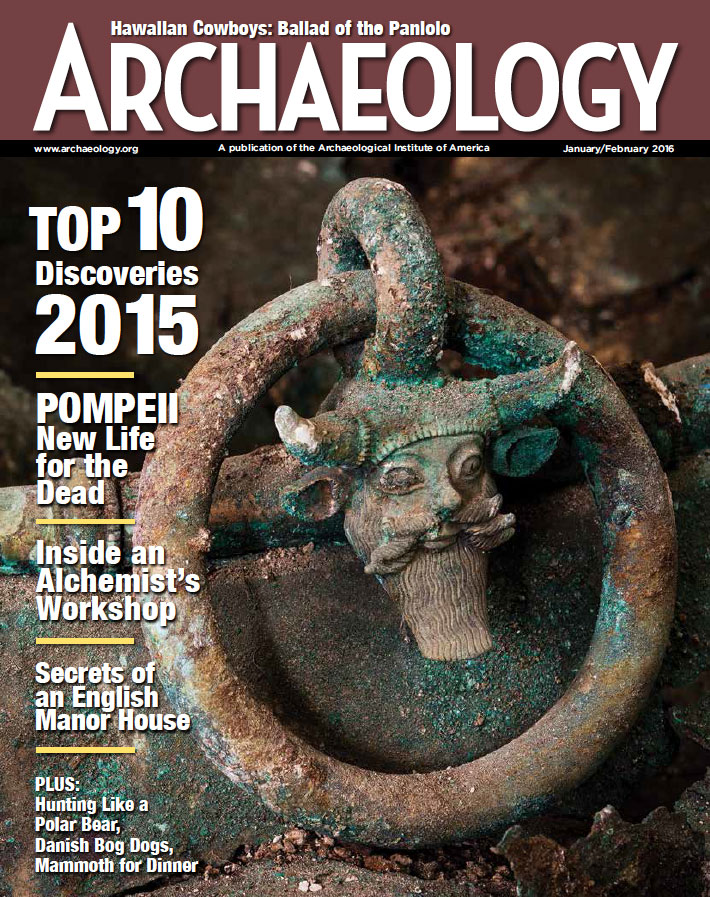

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

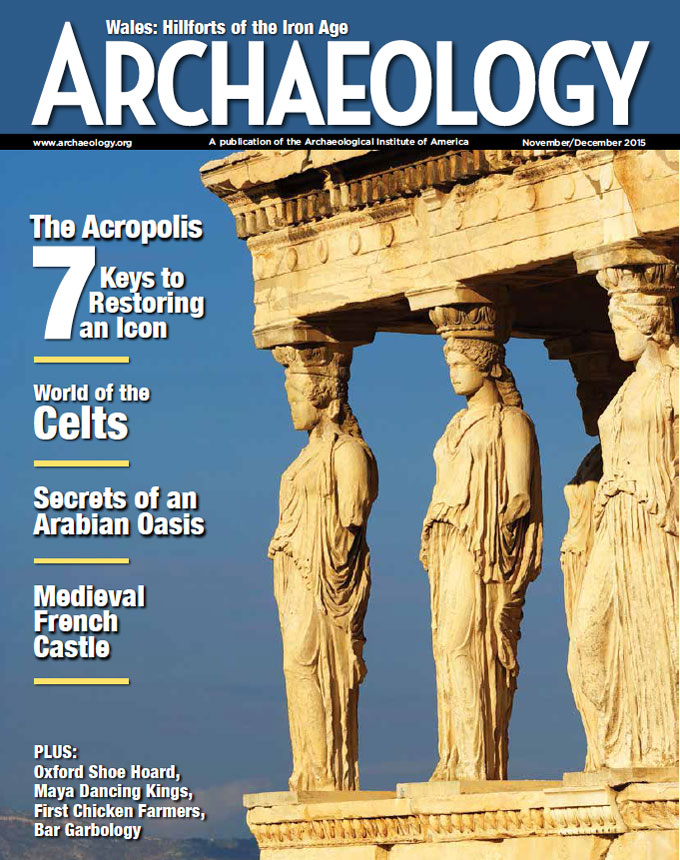

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

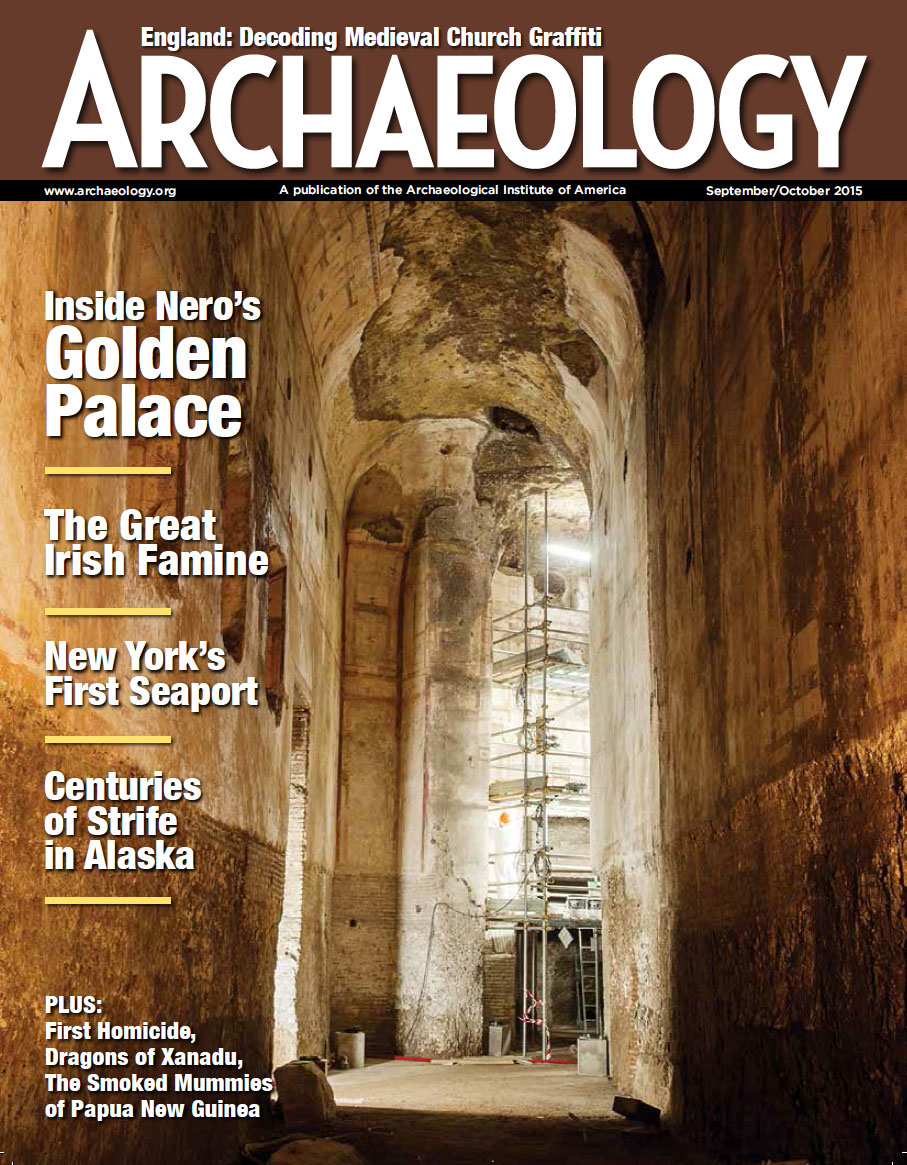

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

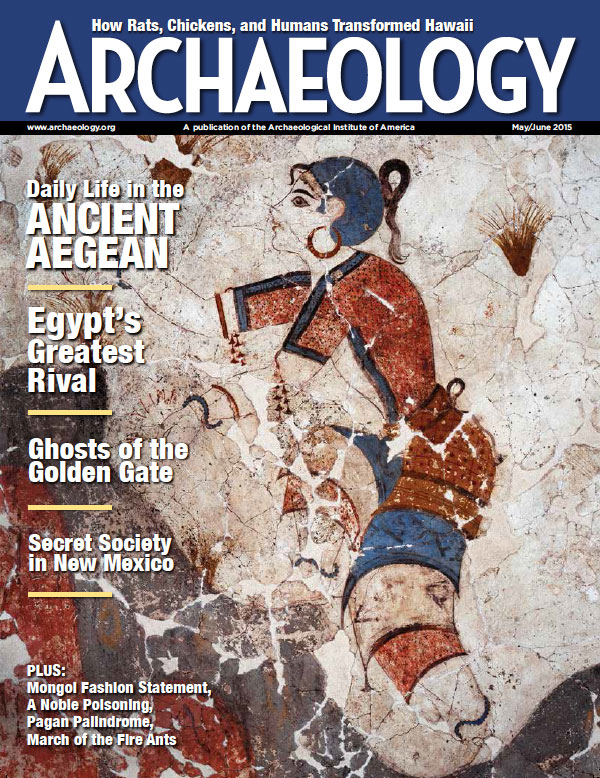

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

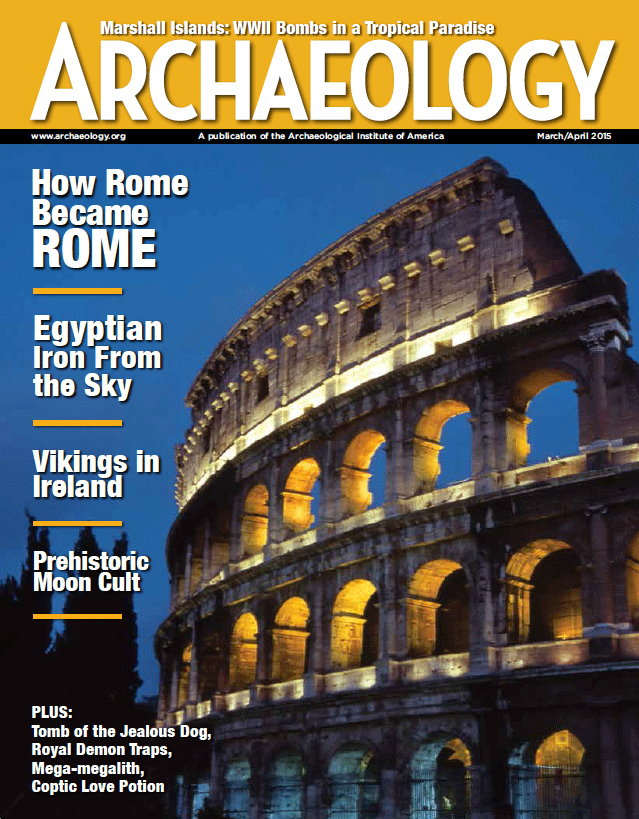

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

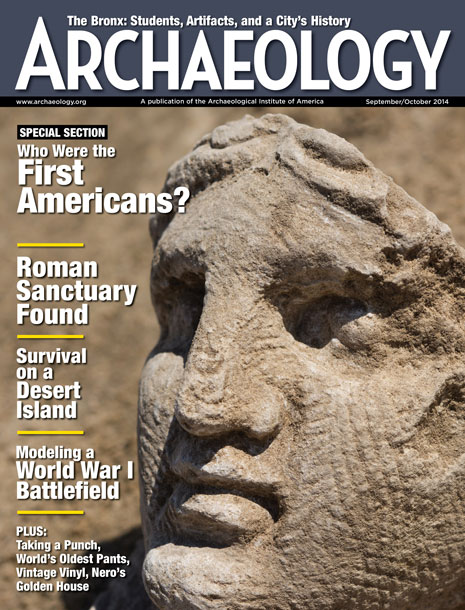

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

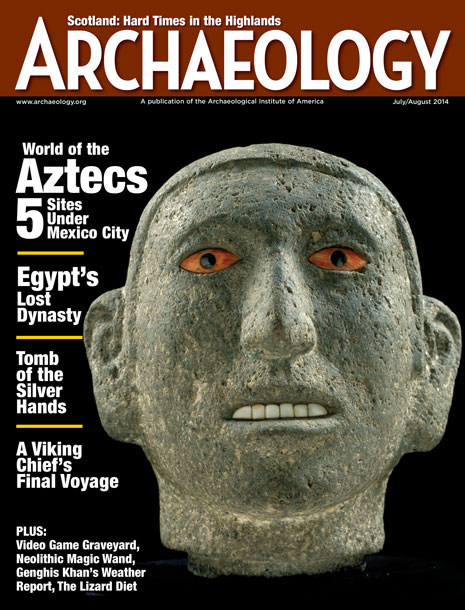

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

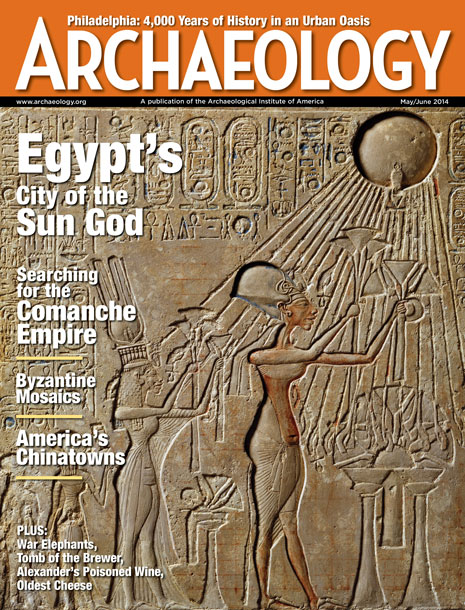

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

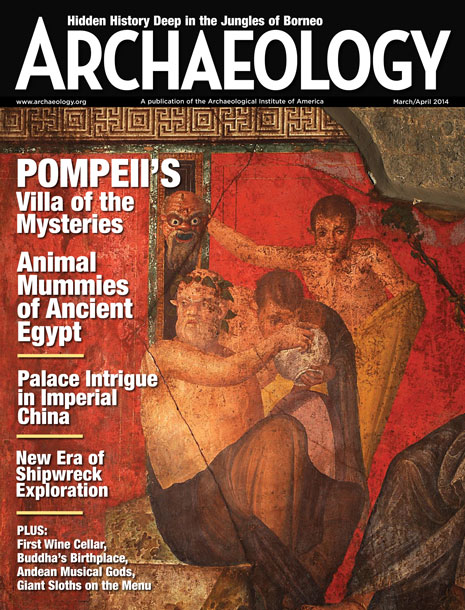

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

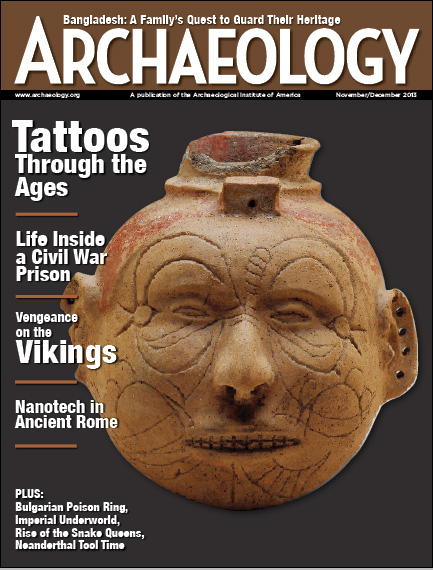

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

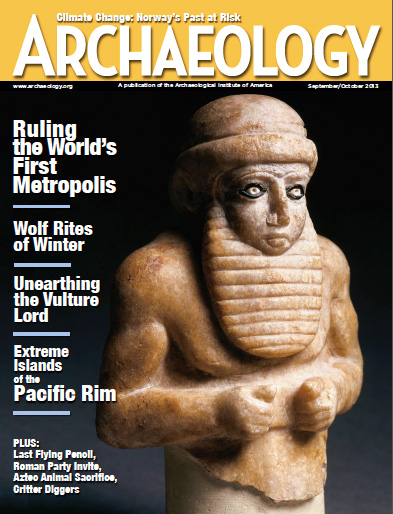

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

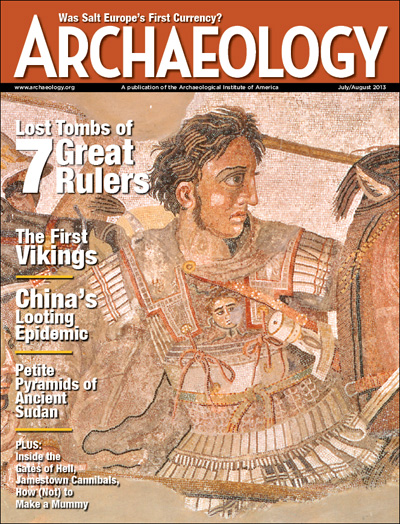

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

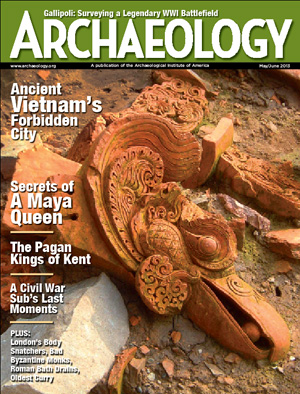

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

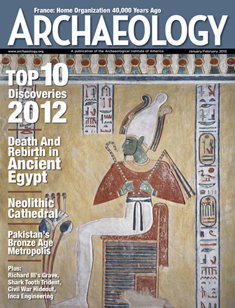

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

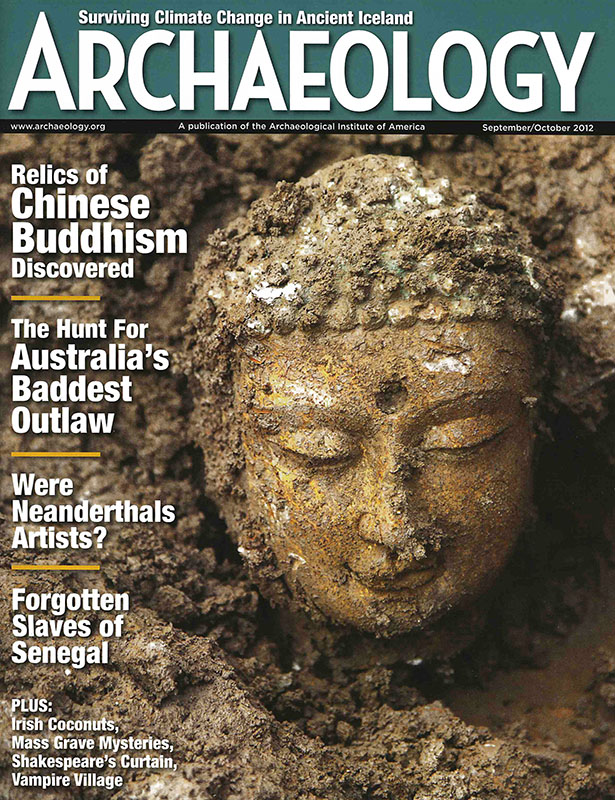

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

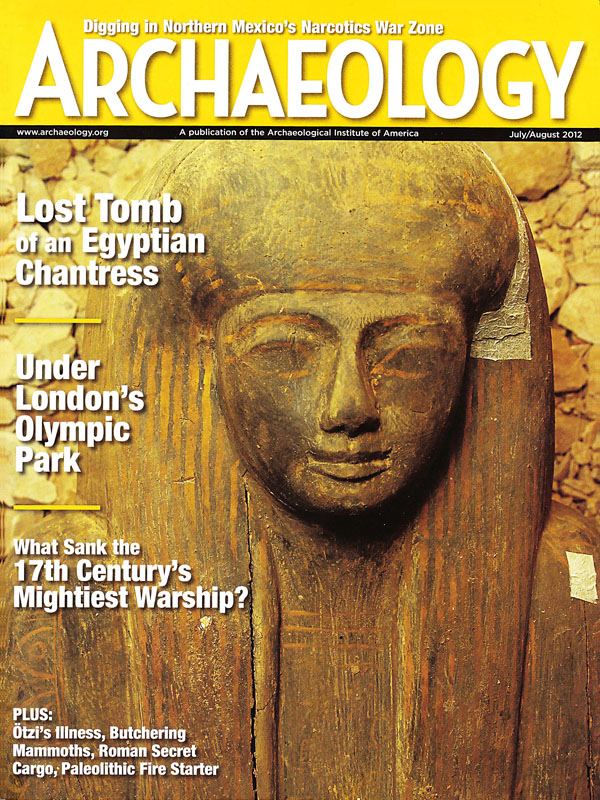

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

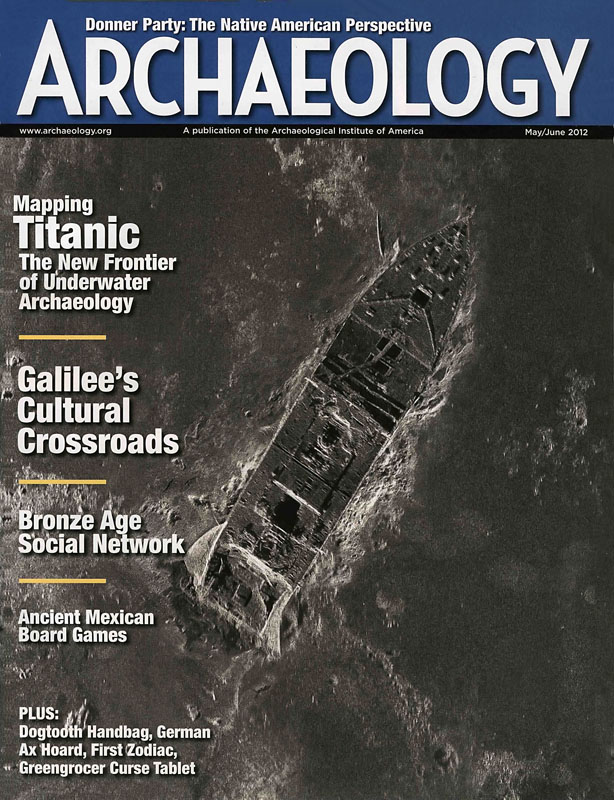

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement

Artifacts found at the site, in the form of lustrous dining pottery called northern black polished ware, along with the coins, indicate that the people living there had considerable purchasing power, according to Shahnaj Husne Jahan of the University of Liberal Arts Bangladesh. That wealth, it is thought by some, might have come from a trade in beads. Numerous semiprecious stones, including carnelian, quartz, agate, and amethyst, in many different shapes, such as cylindrical, diamond, and spherical, have been found at the site. Flakes, cores, and other discard material were also discovered. Bead-making very likely took place at Wari-Bateshwar. And some of these locally produced semiprecious beads are found as far east as the Philippines and Indonesia, suggesting possible trade links between Wari-Bateshwar and Southeast Asia.

Artifacts found at the site, in the form of lustrous dining pottery called northern black polished ware, along with the coins, indicate that the people living there had considerable purchasing power, according to Shahnaj Husne Jahan of the University of Liberal Arts Bangladesh. That wealth, it is thought by some, might have come from a trade in beads. Numerous semiprecious stones, including carnelian, quartz, agate, and amethyst, in many different shapes, such as cylindrical, diamond, and spherical, have been found at the site. Flakes, cores, and other discard material were also discovered. Bead-making very likely took place at Wari-Bateshwar. And some of these locally produced semiprecious beads are found as far east as the Philippines and Indonesia, suggesting possible trade links between Wari-Bateshwar and Southeast Asia. Analysis of 20 of the hundreds of beads found at the site challenges the idea that they are in fact, Indo-Pacific samples. Bead historian James Lankton, of the University College London Institute of Archaeology, says, nonetheless, “There is still an interesting story to tell from the bead material.” His investigation turned up strong links with north India and evidence of material coming from as far south as Sri Lanka.

Analysis of 20 of the hundreds of beads found at the site challenges the idea that they are in fact, Indo-Pacific samples. Bead historian James Lankton, of the University College London Institute of Archaeology, says, nonetheless, “There is still an interesting story to tell from the bead material.” His investigation turned up strong links with north India and evidence of material coming from as far south as Sri Lanka.