New Thoughts on Africa’s Pastoral Environments

Tuesday, March 10, 2015

ST LOUIS, MISSOURI—It had been thought that the tsetse fly, which carries sleeping sickness and nagana and thrives in bushy woodlands, stopped the spread of herders of domesticated animals into southern Africa some 2,000 years ago. Fiona Marshall of Washington University has led a team of researchers who analyzed the isotopes in animal teeth from a 2,000-year-old settlement near Gogo Falls in southern Kenya. The people who lived there ate a varied diet that included domestic and wild food sources. The region is now made up of bushy woodlands, but the results of the study suggest that there had been abundant grassland vegetation for the animals to eat in what may have been a grass-woodland transition zone. So did the human residents consume wild food because tsetse flies damaged their livestock herds? “Our findings challenge existing models that explain the settlement’s diverse diet as a consequence of depressed livestock production related to tsetse flies. Instead of this ecological explanation, our isotopic findings support the notion that herders may simply have interacted with hunter-gatherer groups already living in these areas, adapting to their foraging styles. This suggests that social factors may have played a greater role than previously thought in subsistence diversity during the spread of pastoralism in Eastern Africa,” Marshall explained. Changes in rainfall, grazing by wild herbivores, and burning of land by the herders may have maintained the savanna for the livestock and provided a corridor through the Lake Victoria basin for the migration of pastoralists into southern Africa. To read about a fascinating archaeological discovery made in southern Africa, see "First Use of Poison."

ST LOUIS, MISSOURI—It had been thought that the tsetse fly, which carries sleeping sickness and nagana and thrives in bushy woodlands, stopped the spread of herders of domesticated animals into southern Africa some 2,000 years ago. Fiona Marshall of Washington University has led a team of researchers who analyzed the isotopes in animal teeth from a 2,000-year-old settlement near Gogo Falls in southern Kenya. The people who lived there ate a varied diet that included domestic and wild food sources. The region is now made up of bushy woodlands, but the results of the study suggest that there had been abundant grassland vegetation for the animals to eat in what may have been a grass-woodland transition zone. So did the human residents consume wild food because tsetse flies damaged their livestock herds? “Our findings challenge existing models that explain the settlement’s diverse diet as a consequence of depressed livestock production related to tsetse flies. Instead of this ecological explanation, our isotopic findings support the notion that herders may simply have interacted with hunter-gatherer groups already living in these areas, adapting to their foraging styles. This suggests that social factors may have played a greater role than previously thought in subsistence diversity during the spread of pastoralism in Eastern Africa,” Marshall explained. Changes in rainfall, grazing by wild herbivores, and burning of land by the herders may have maintained the savanna for the livestock and provided a corridor through the Lake Victoria basin for the migration of pastoralists into southern Africa. To read about a fascinating archaeological discovery made in southern Africa, see "First Use of Poison."

Advertisement

IN THE CURRENT ISSUE

Digs & Discoveries

Ancient Egyptian Caregivers

Educational Idols

Cleaning Out the Basement

Pompeian Politics

Near Eastern Lip Kit

Turn of the Millennium Falcon

Speaking in Golden Tongues

Workhouse Woes

Hunting Heads

The Amazon’s Urban Roots

Off the Grid

Around the World

Panama’s golden grave, Viking dental exams, an unusual papyrus preservative, playing games in ancient Kenya, and a venerable Venetian church

Artifact

Within a knight’s grasp

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

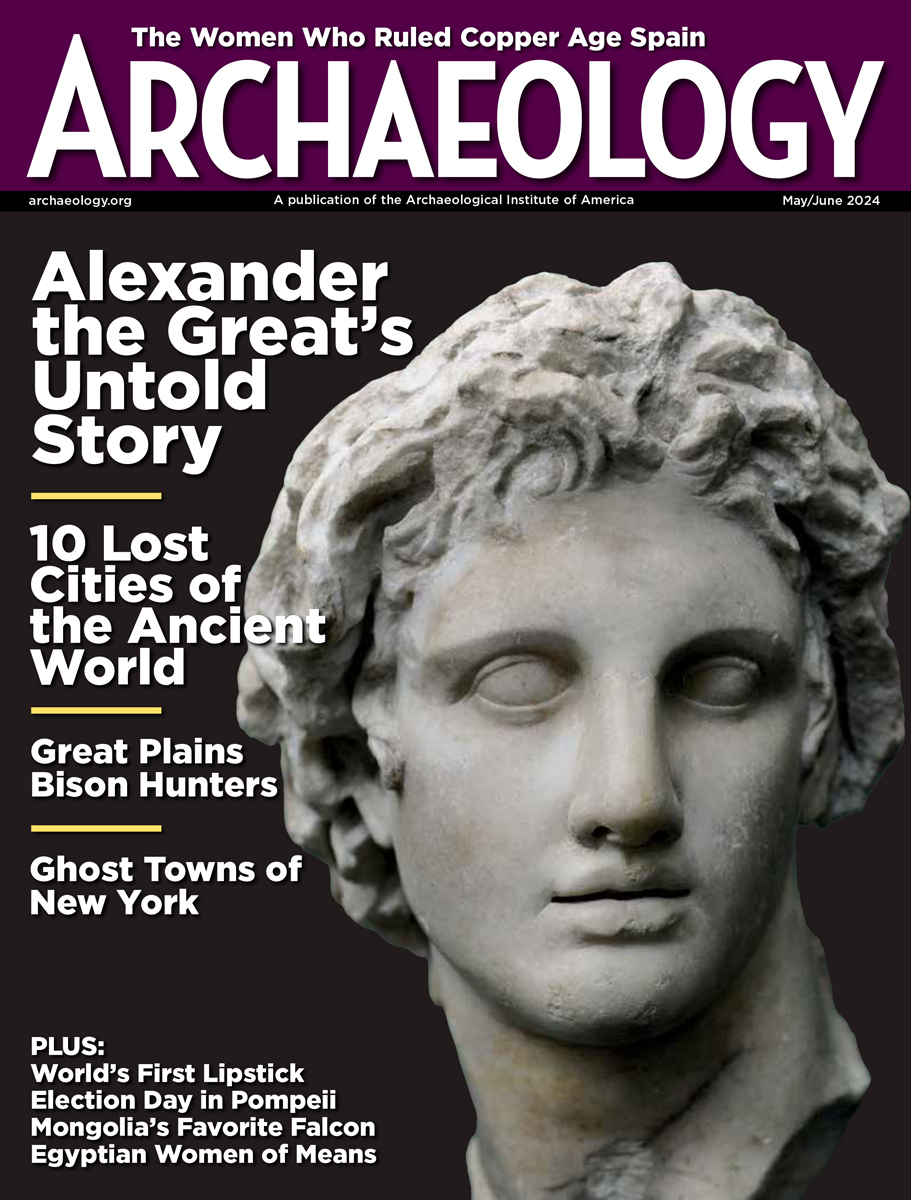

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

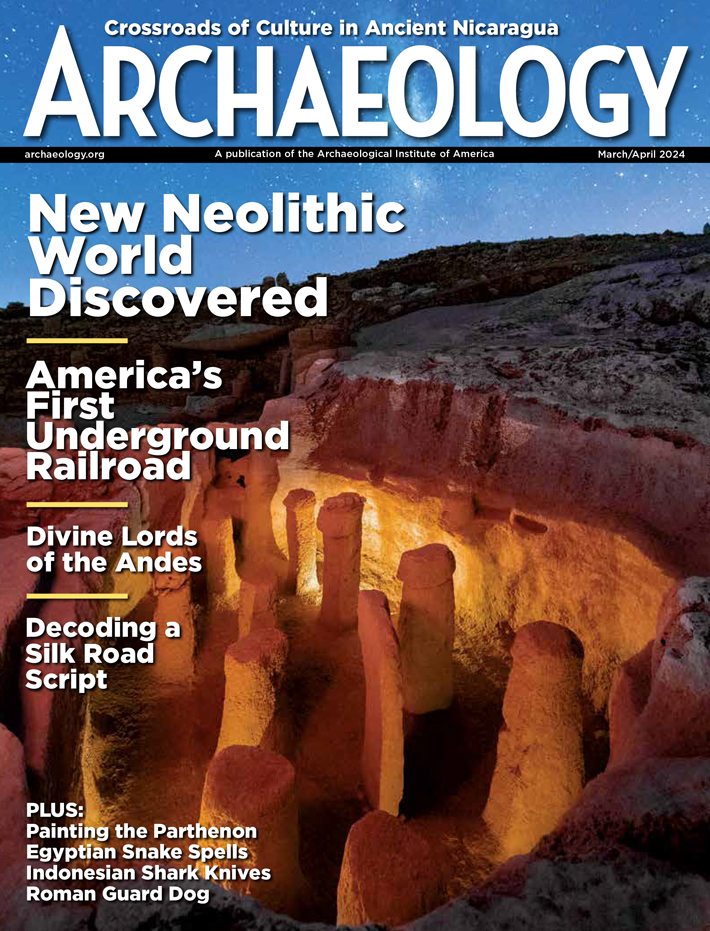

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

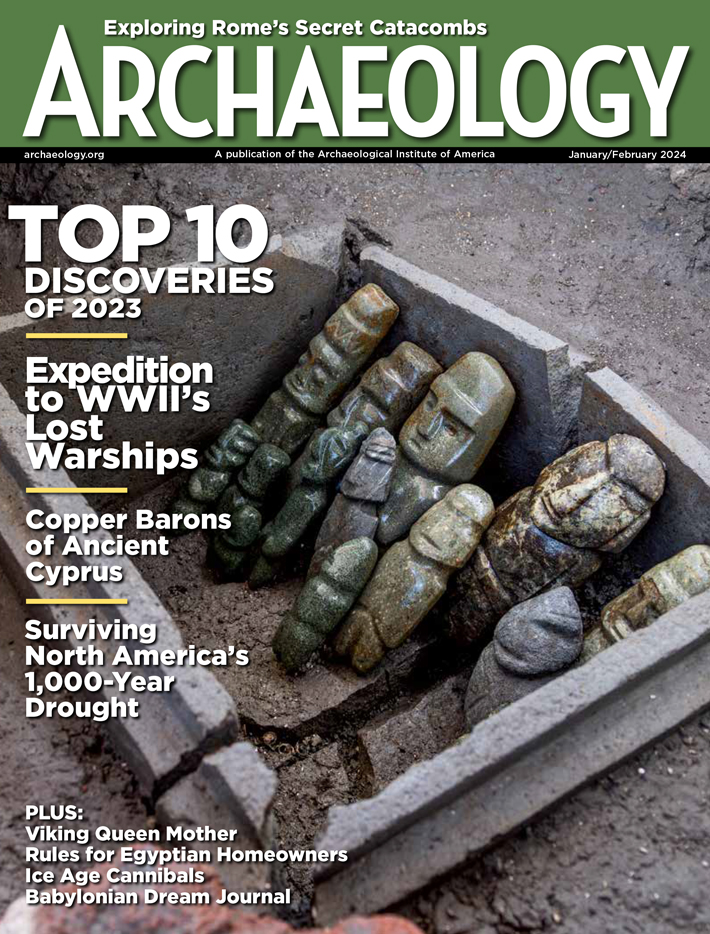

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

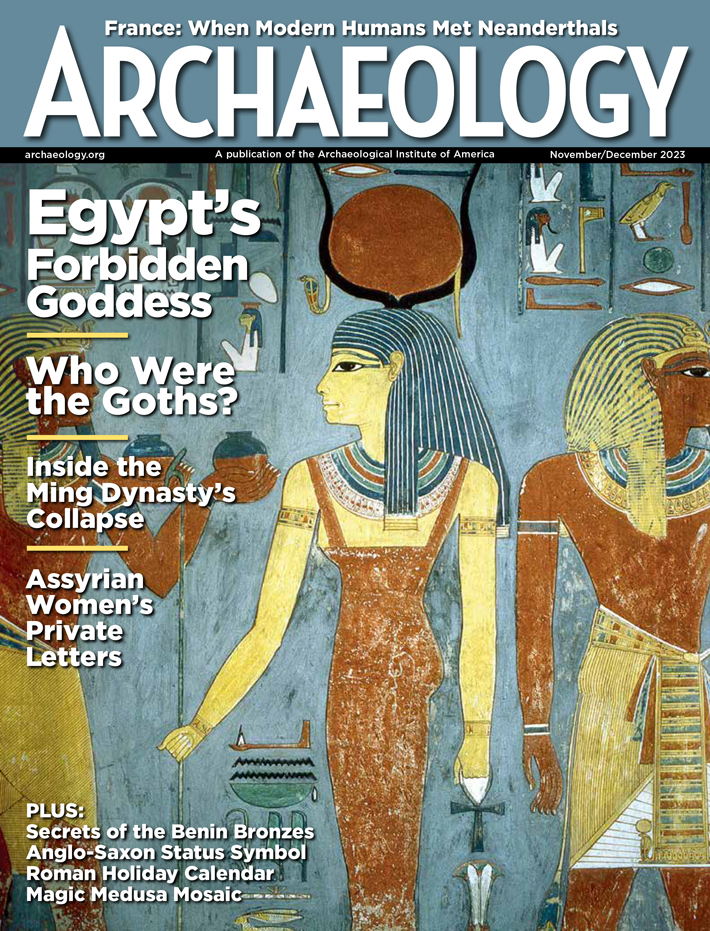

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

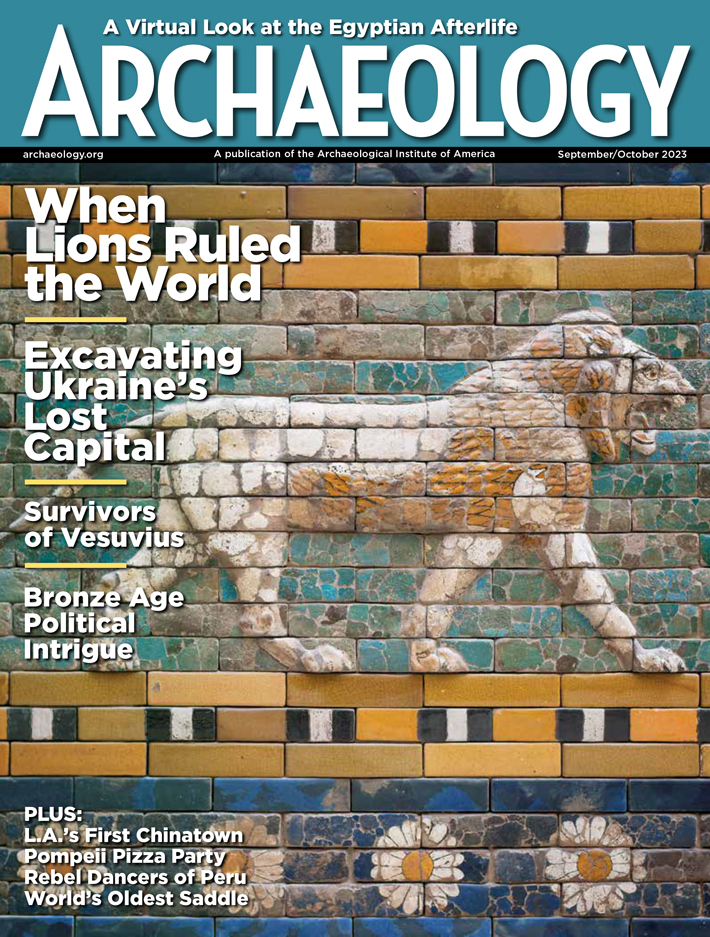

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

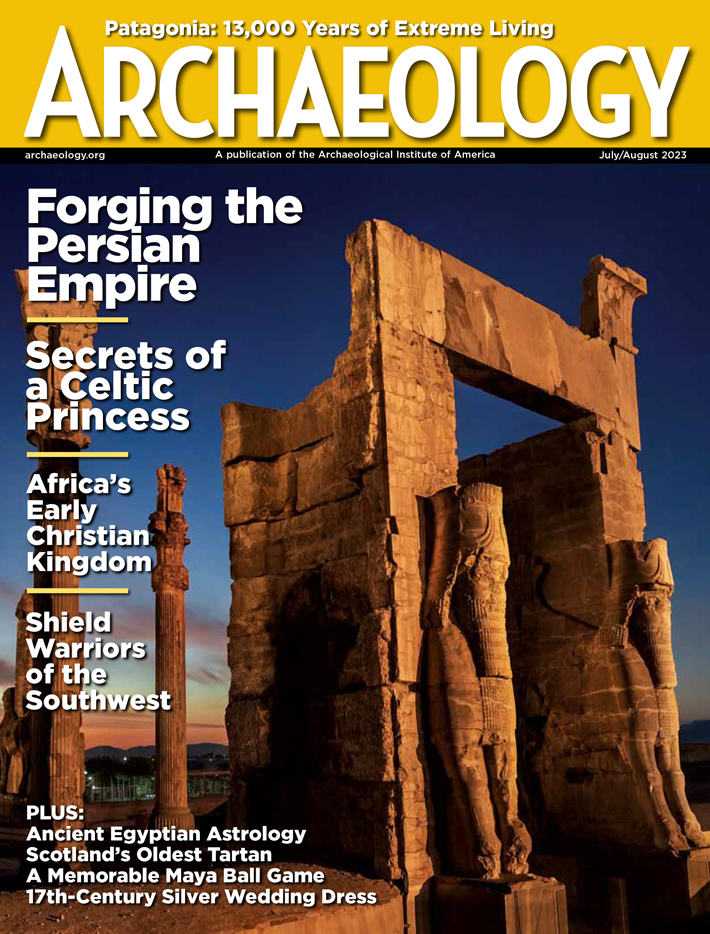

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

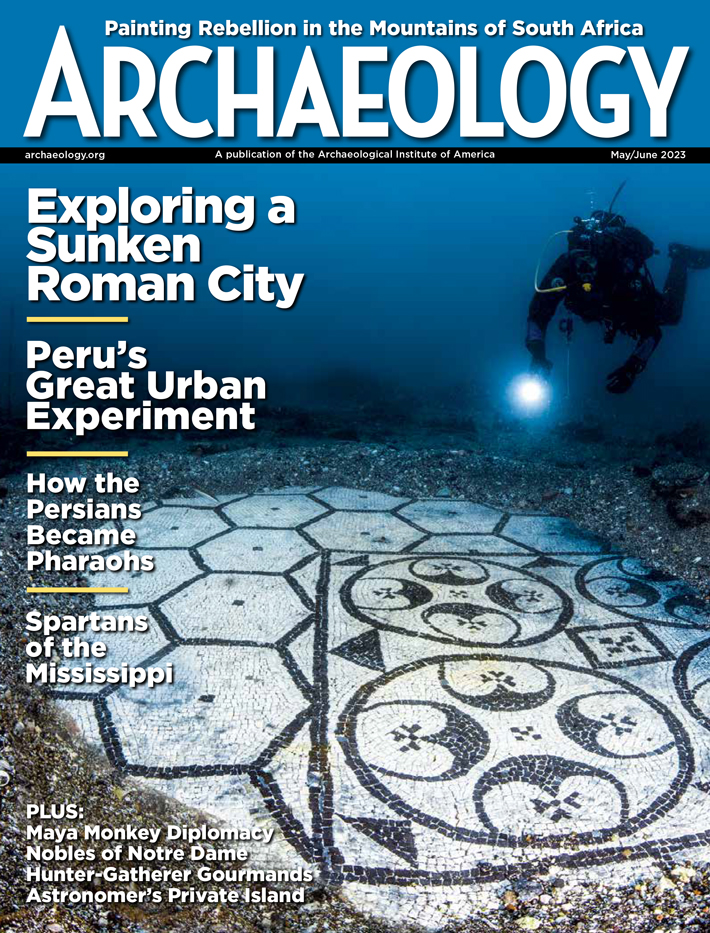

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

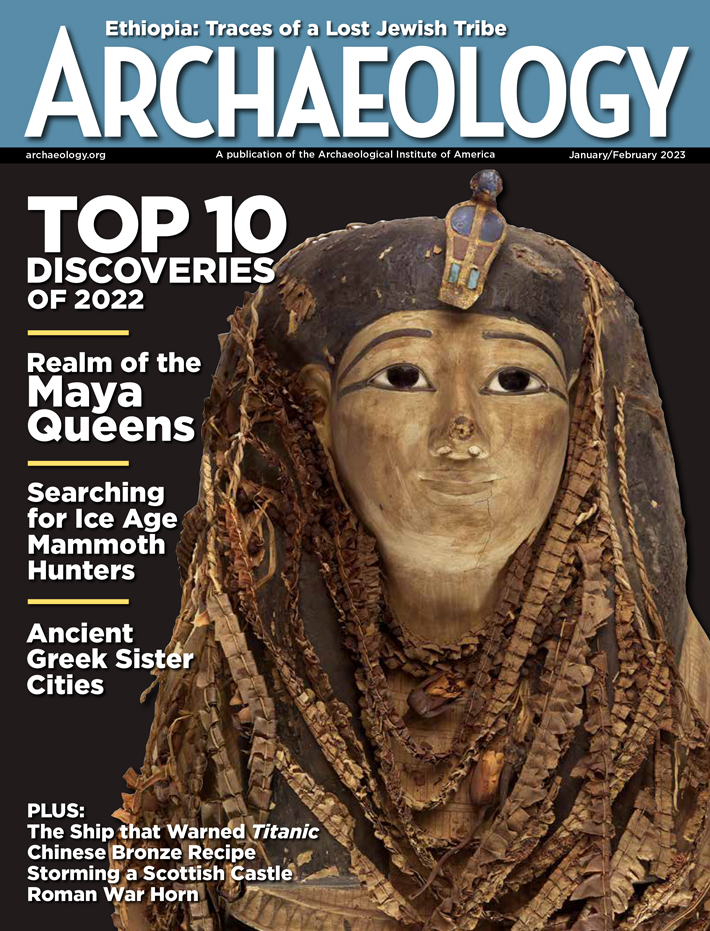

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

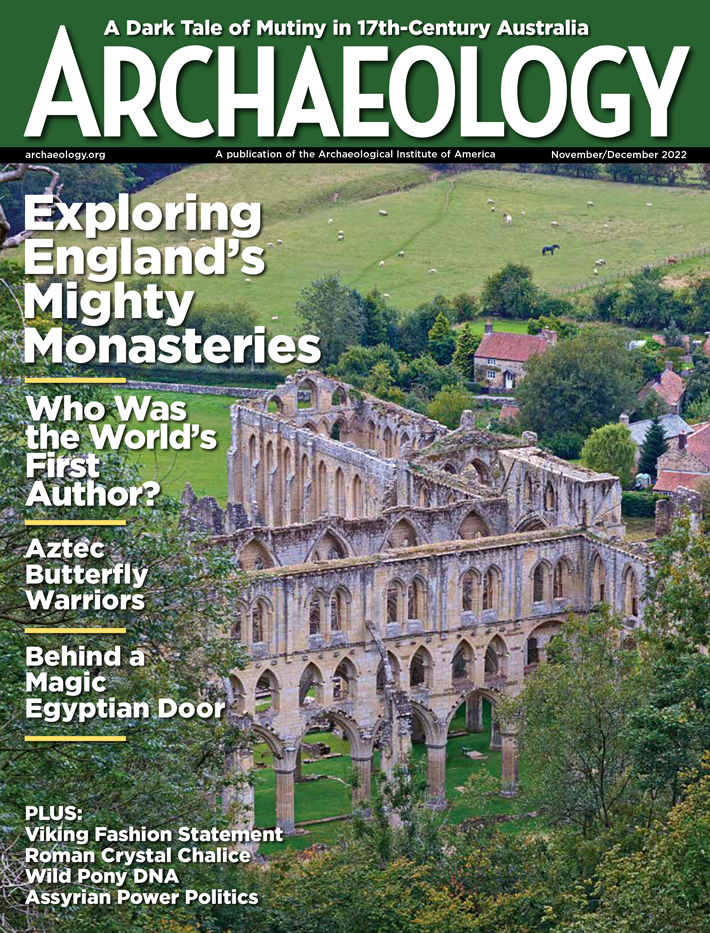

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

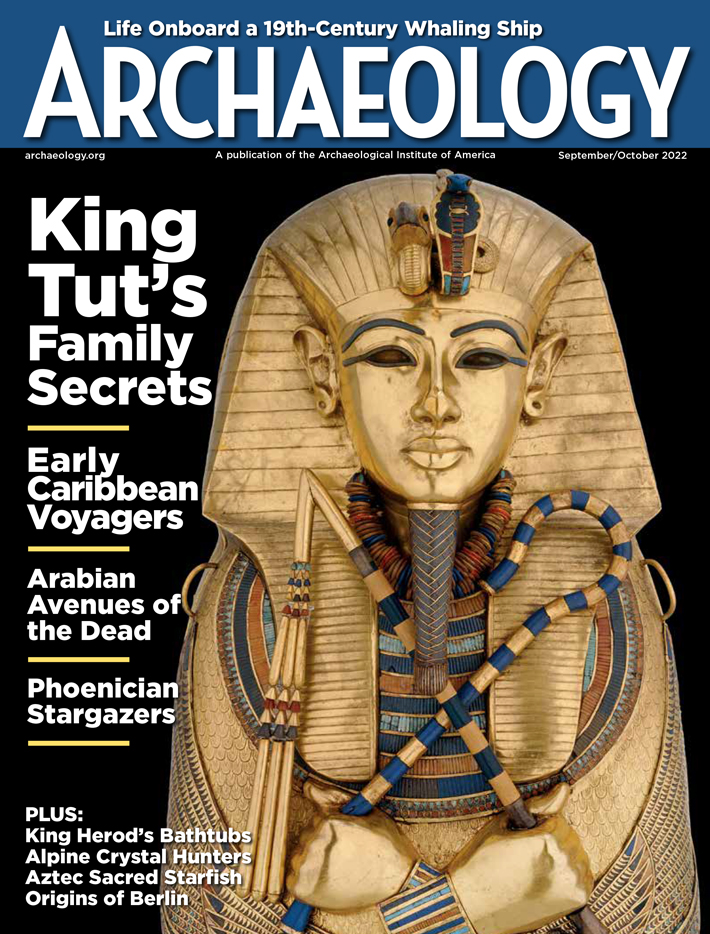

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

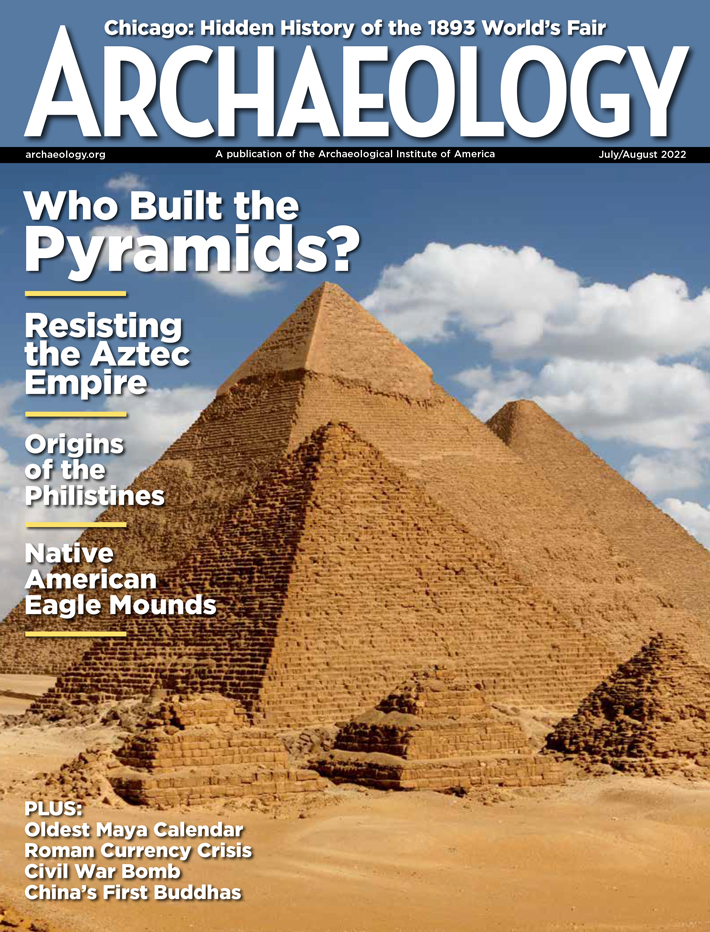

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

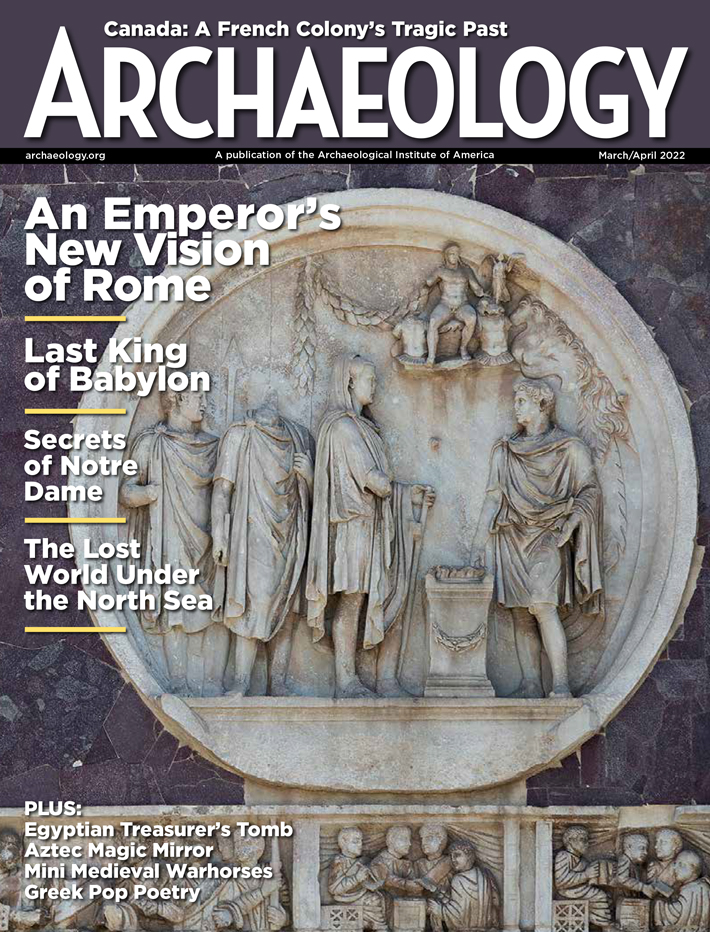

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

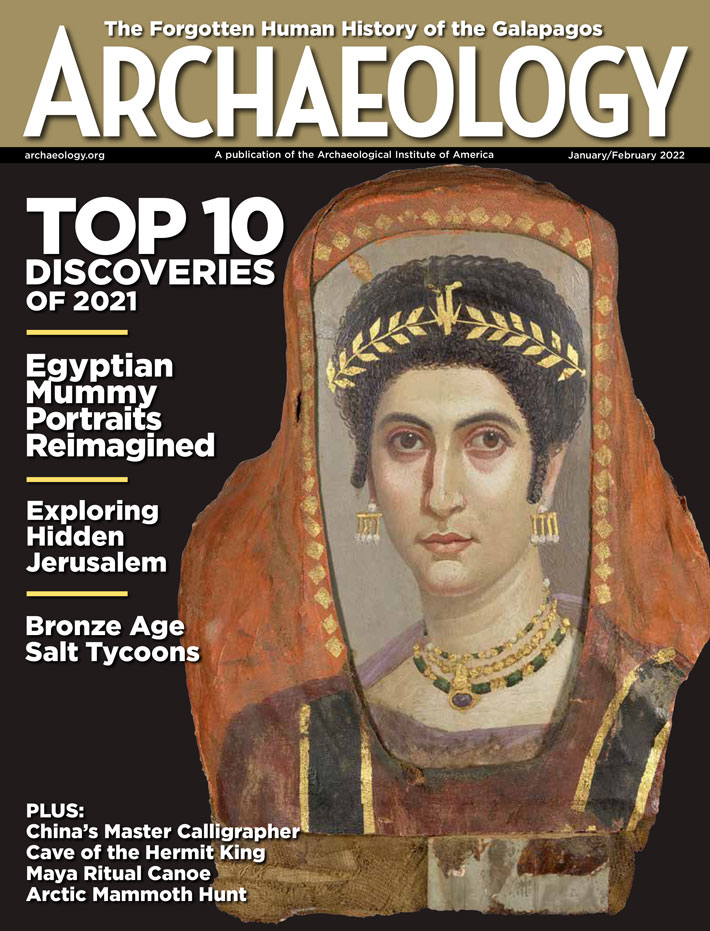

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

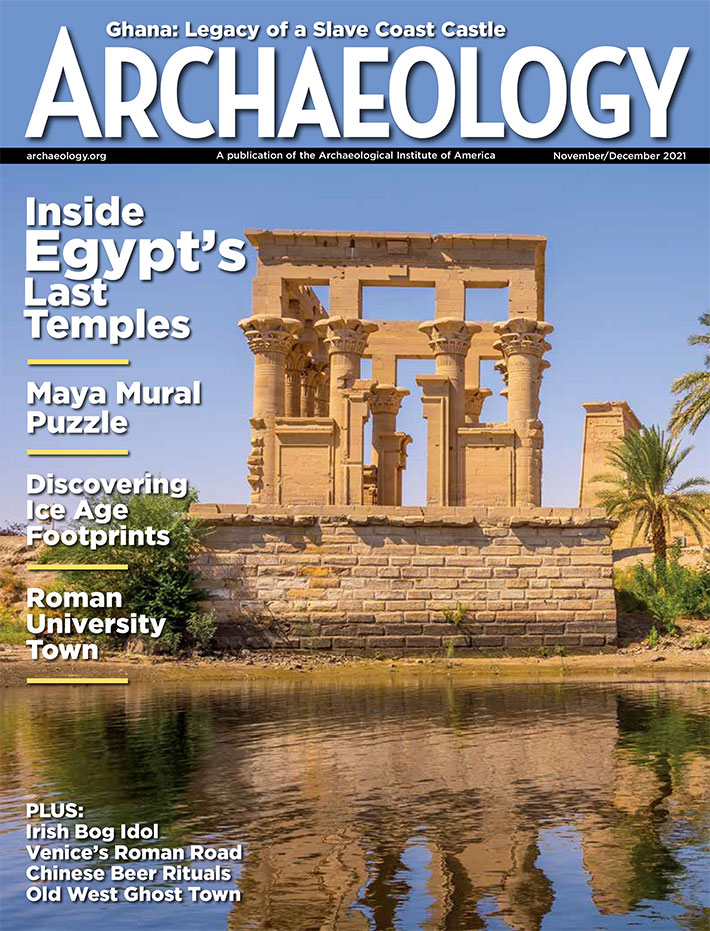

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

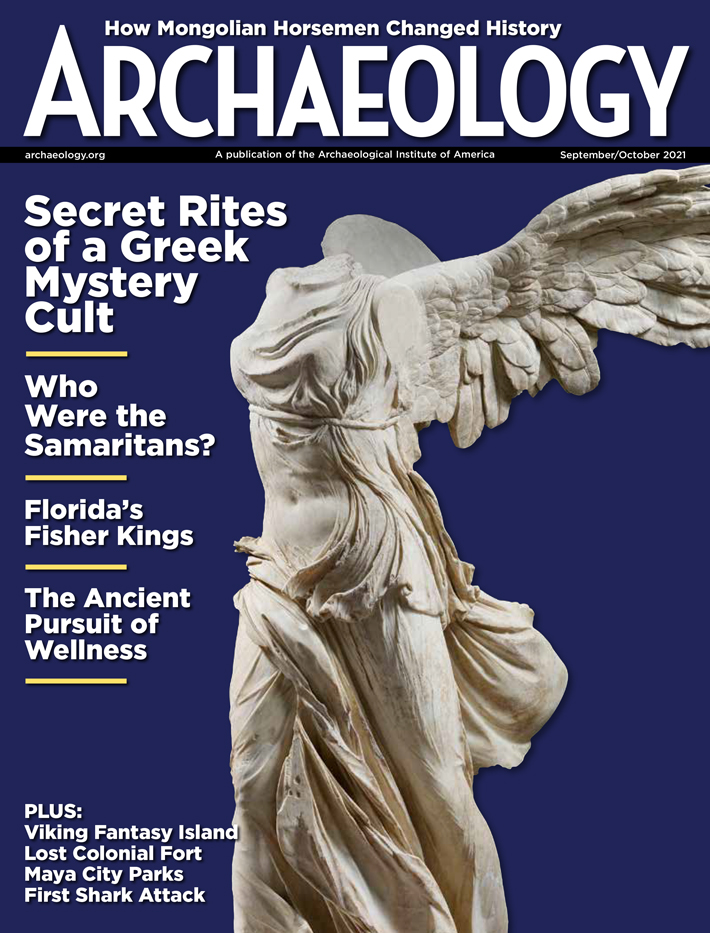

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

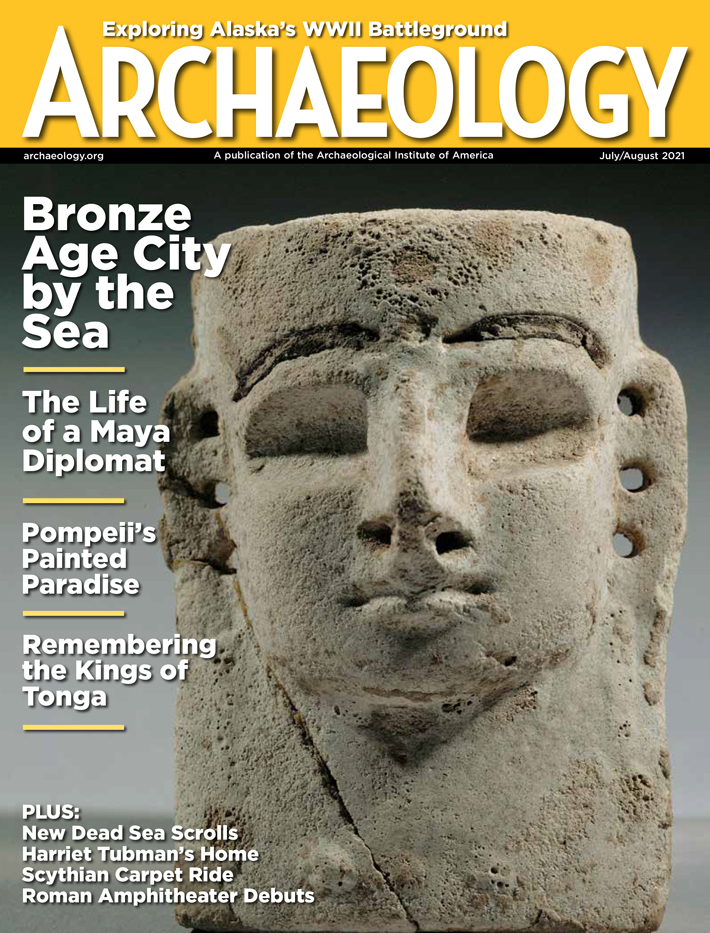

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

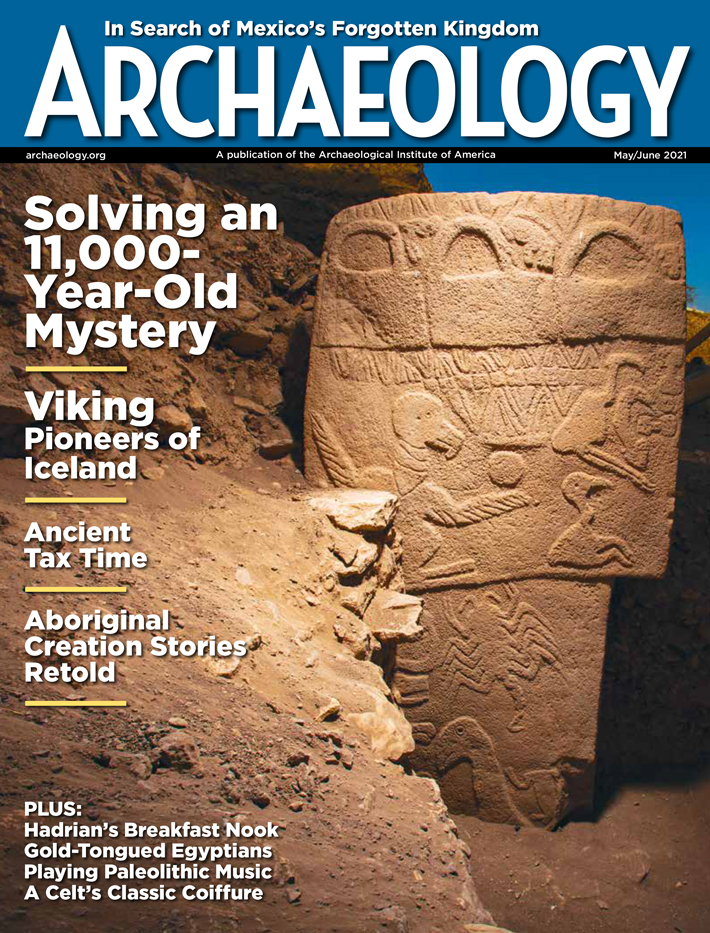

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

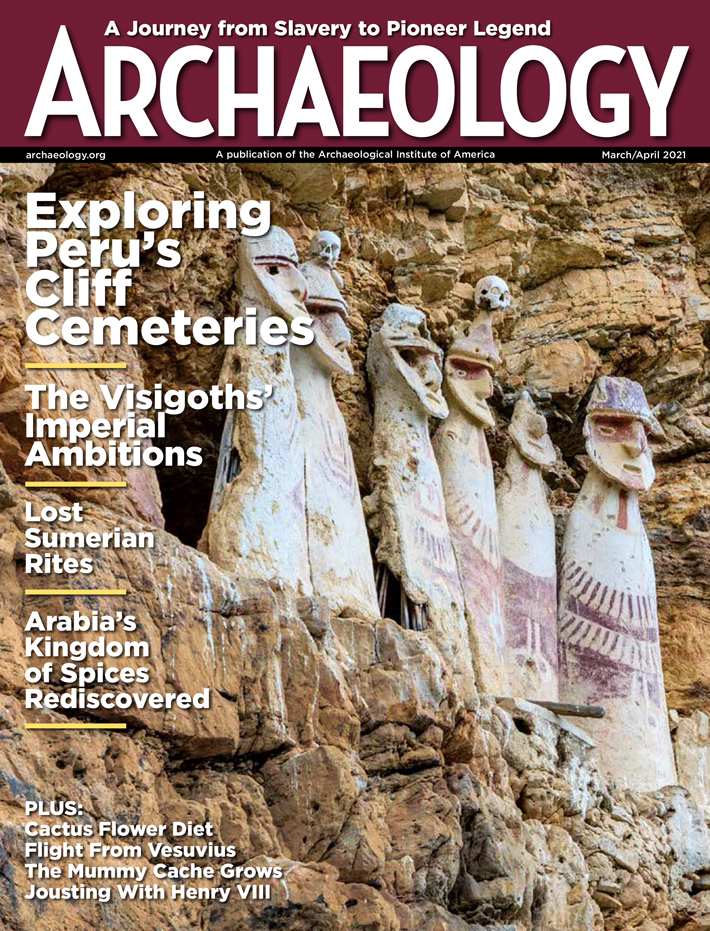

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

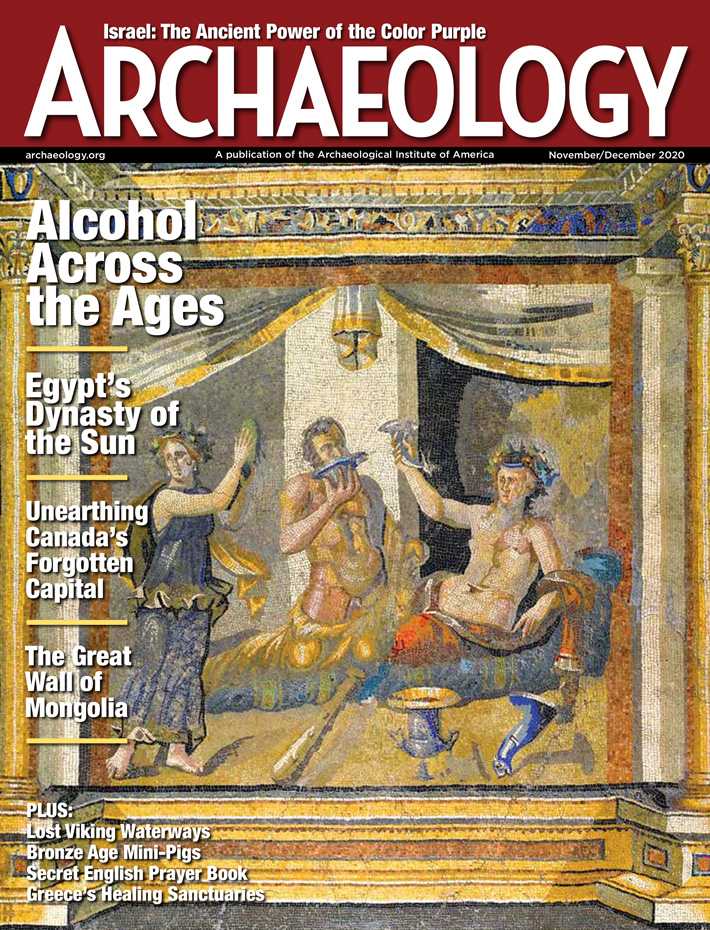

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

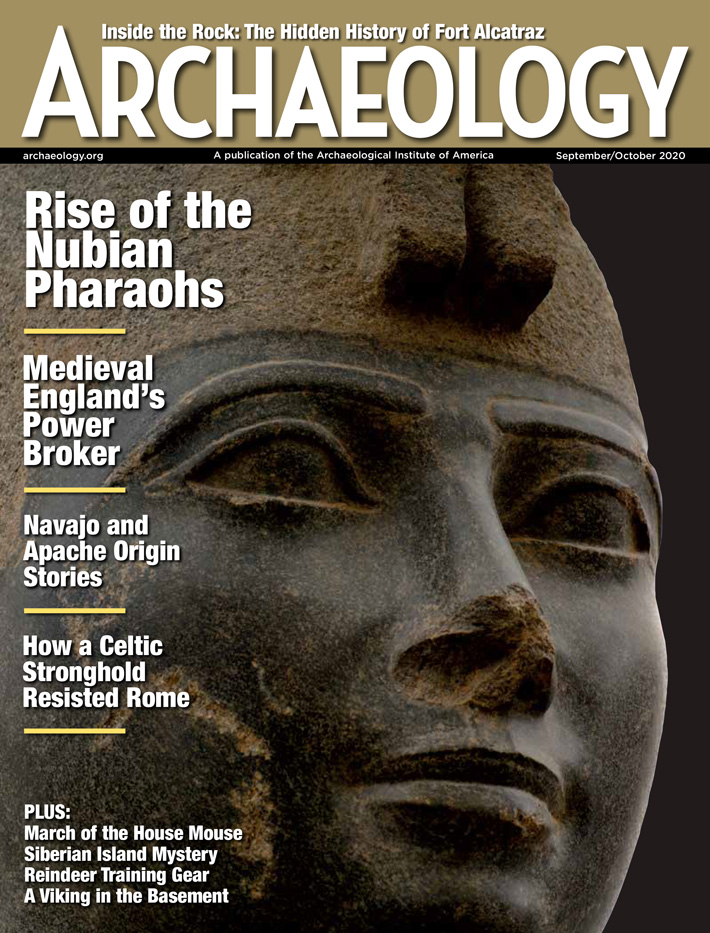

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

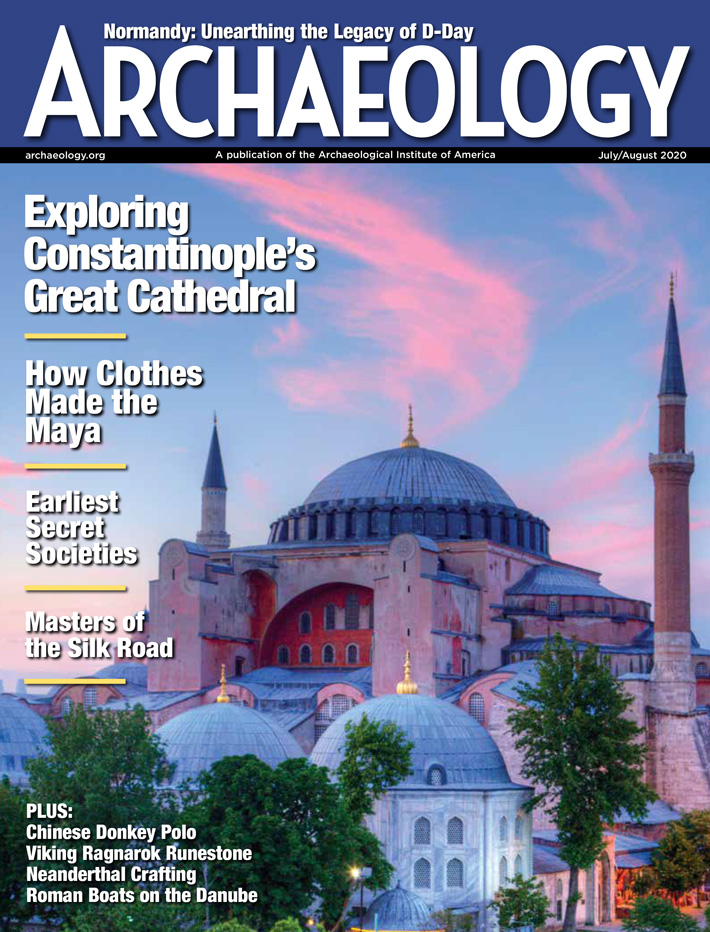

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

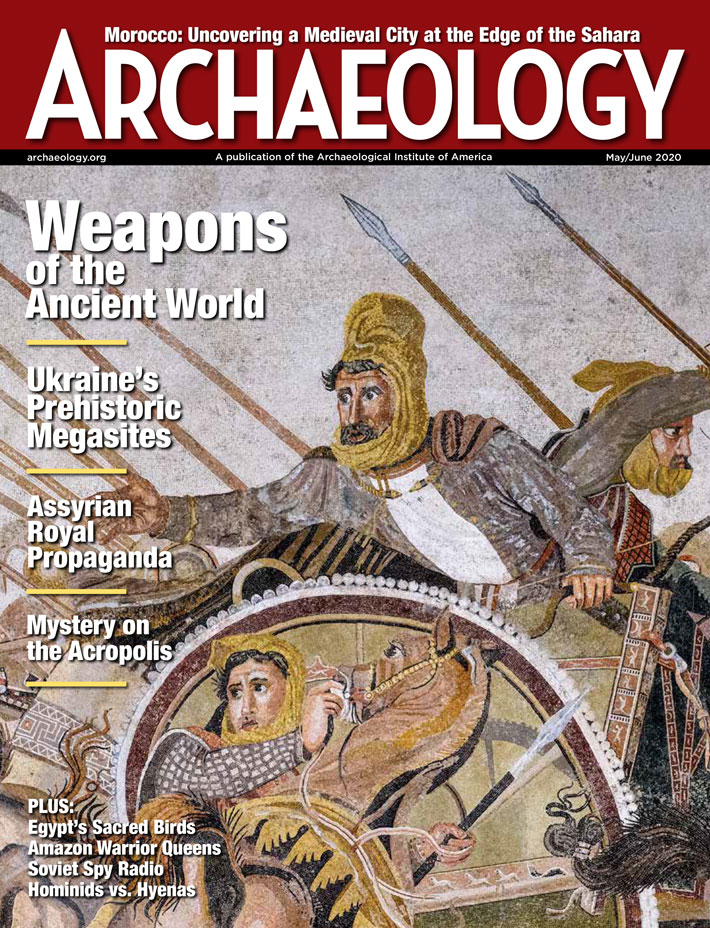

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

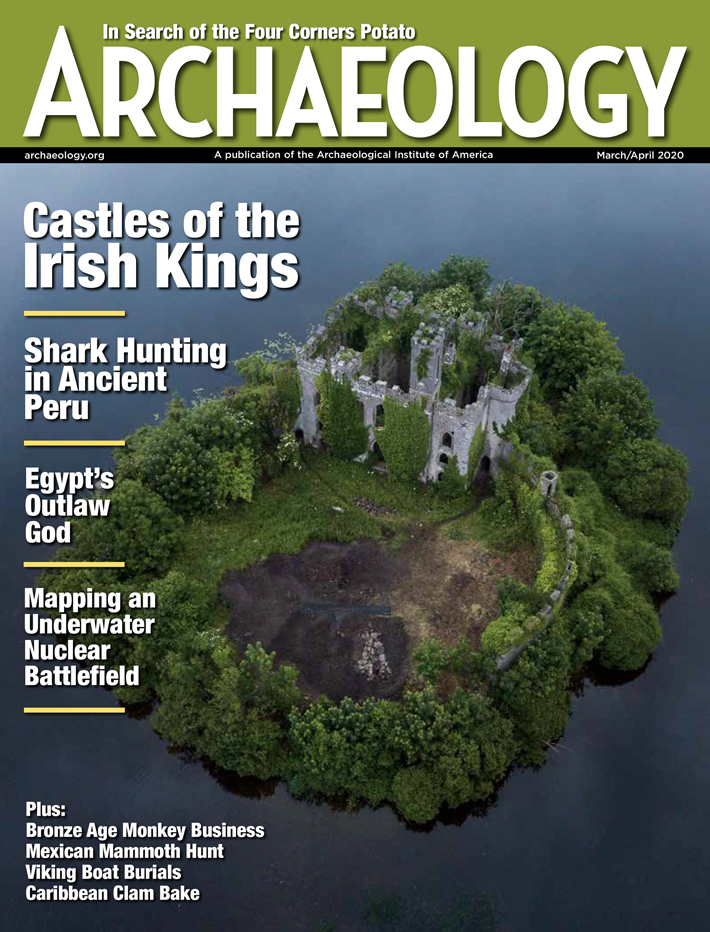

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

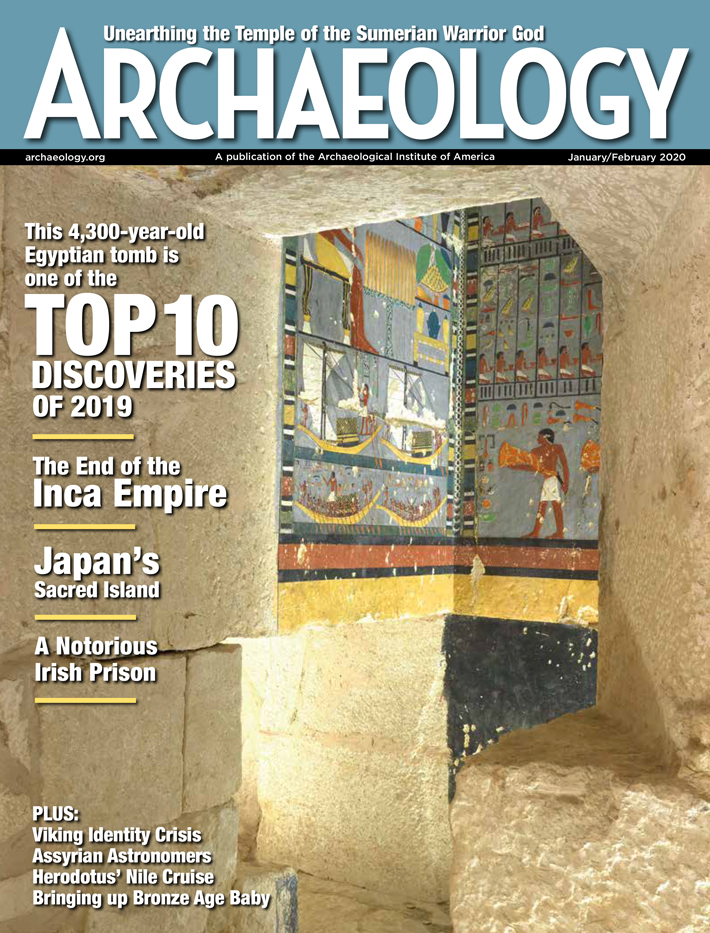

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

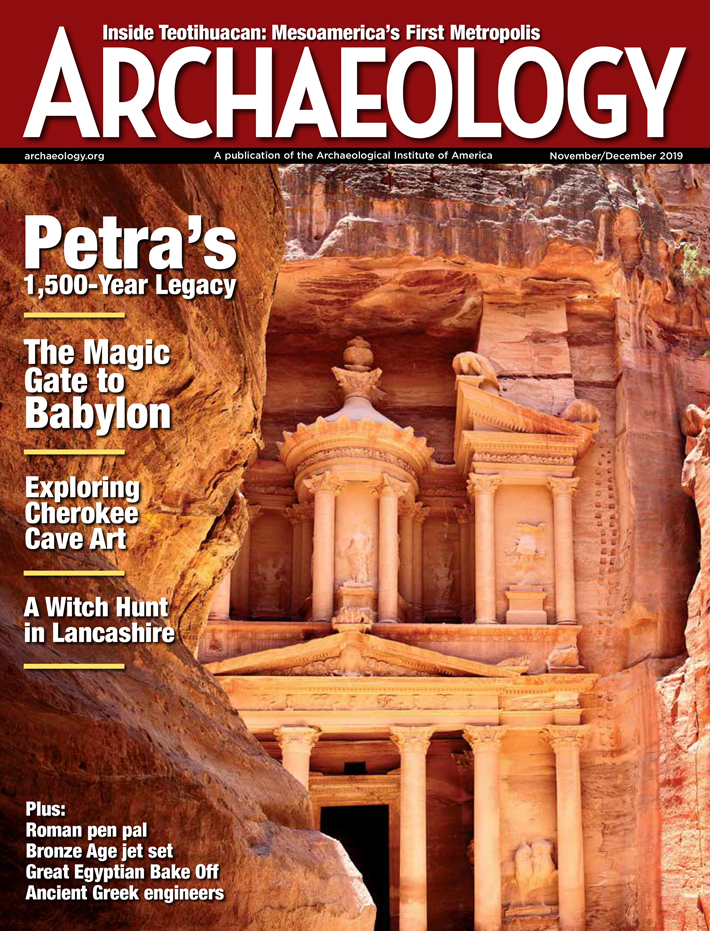

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

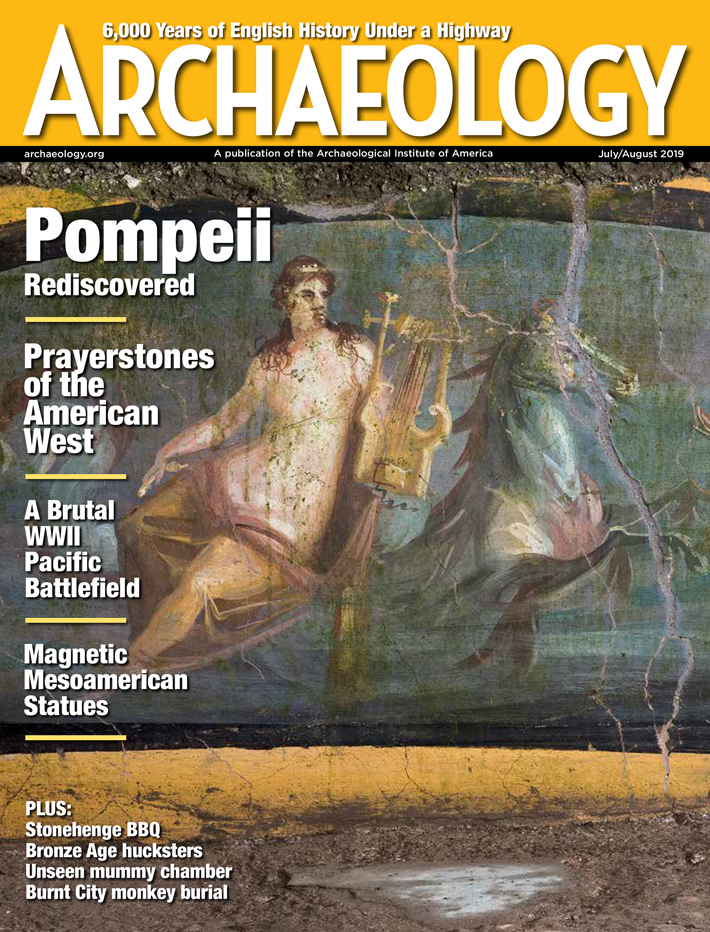

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

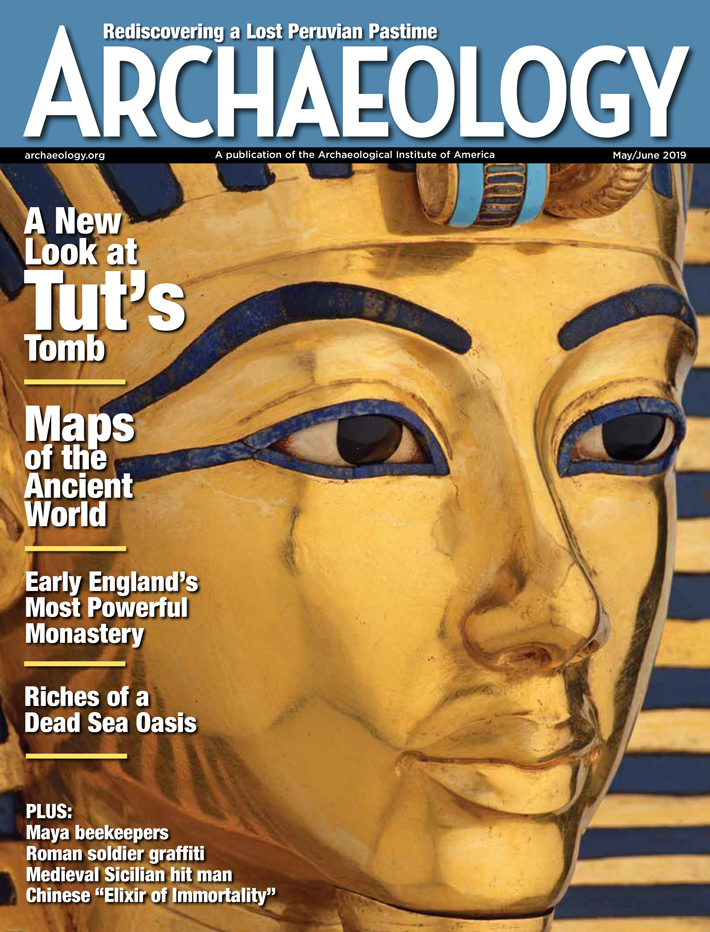

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

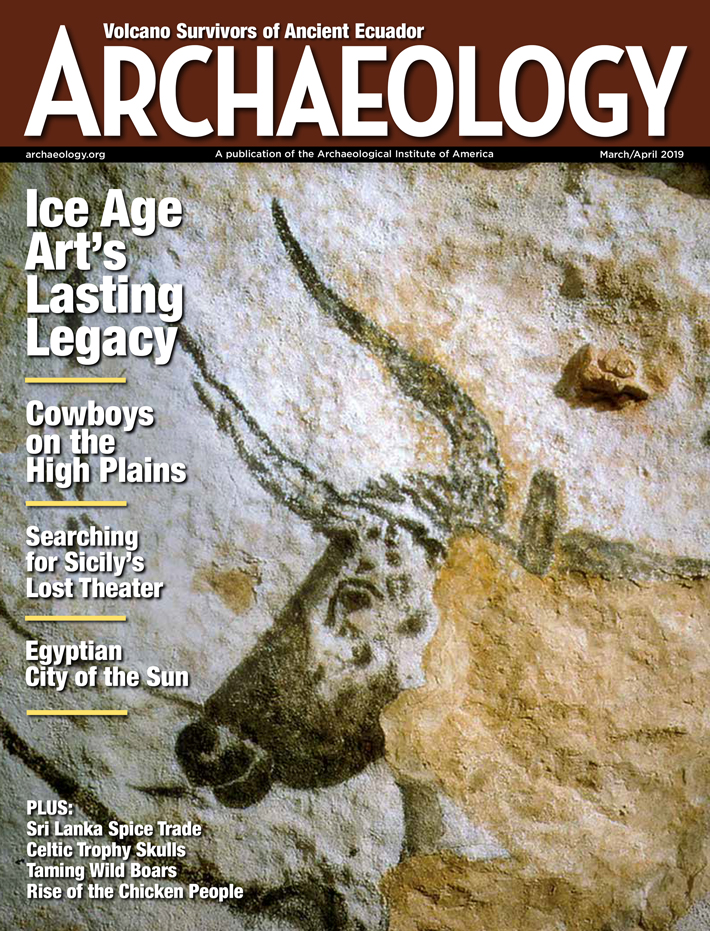

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

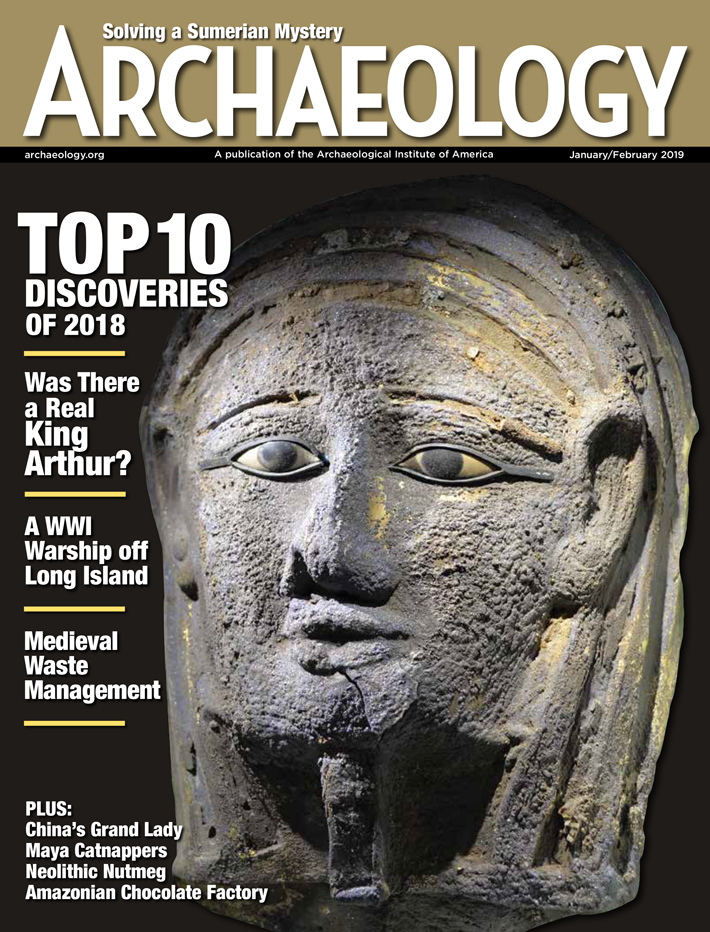

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

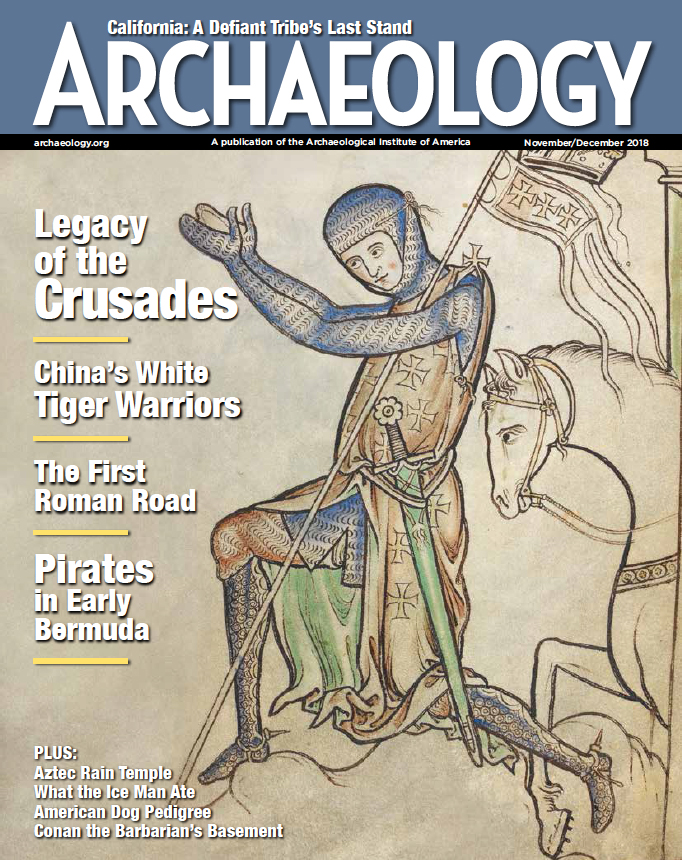

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

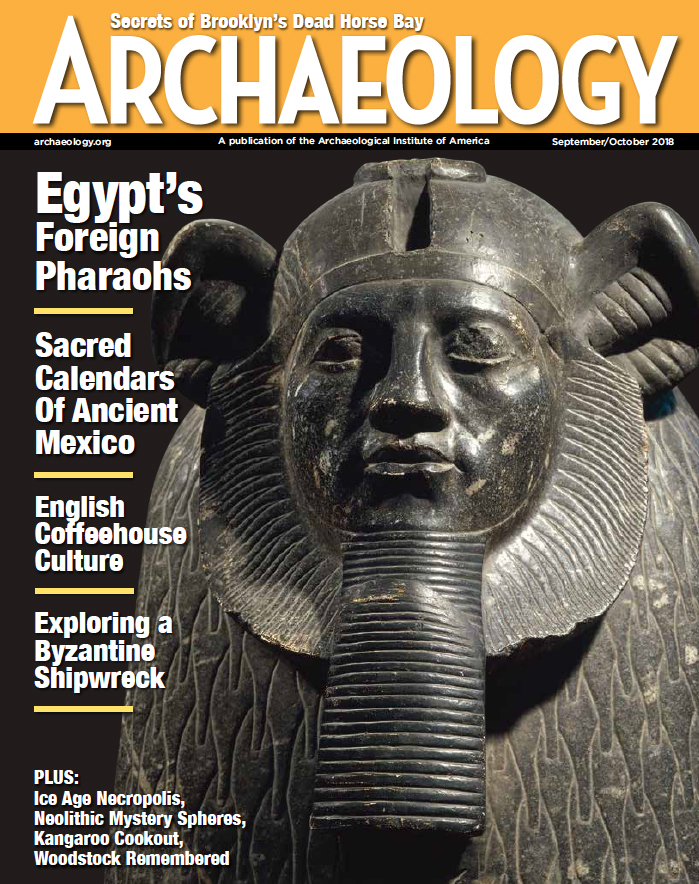

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

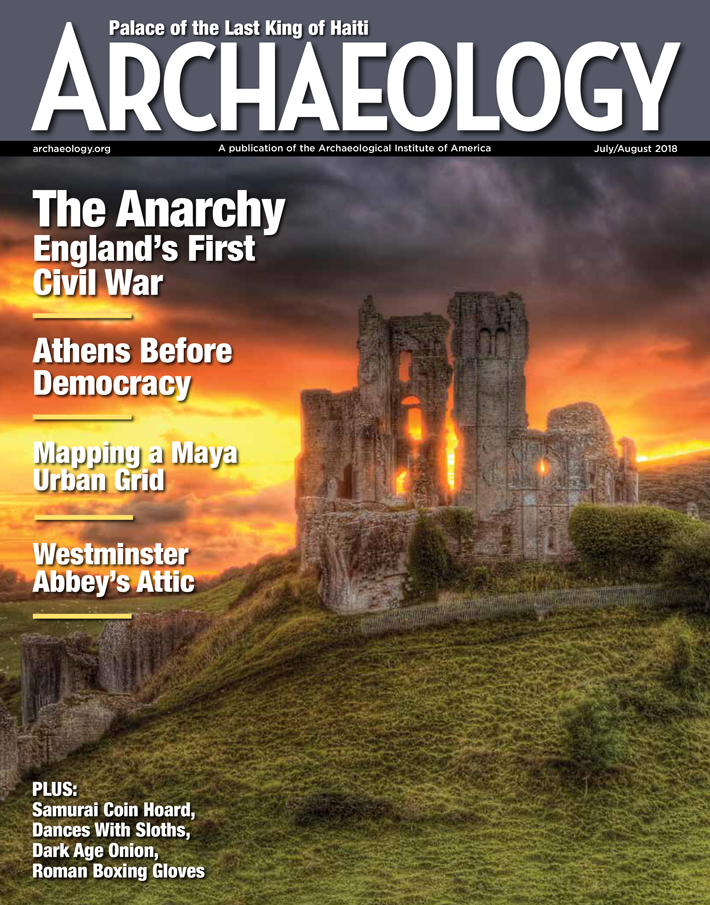

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

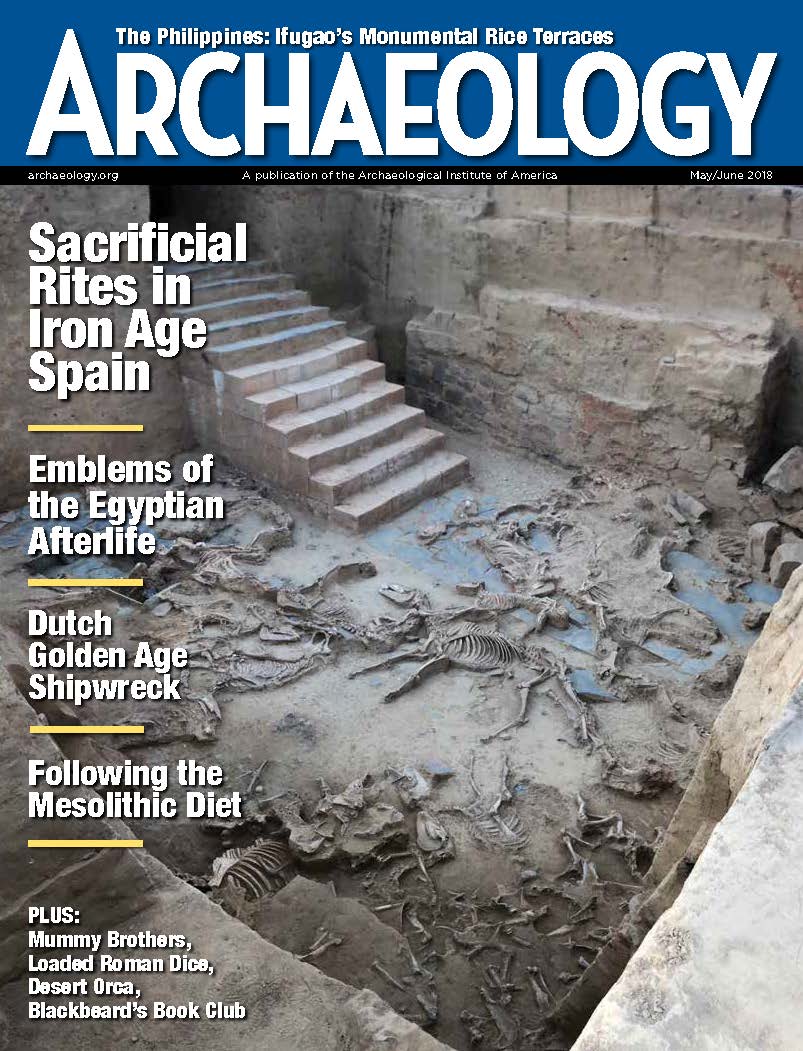

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

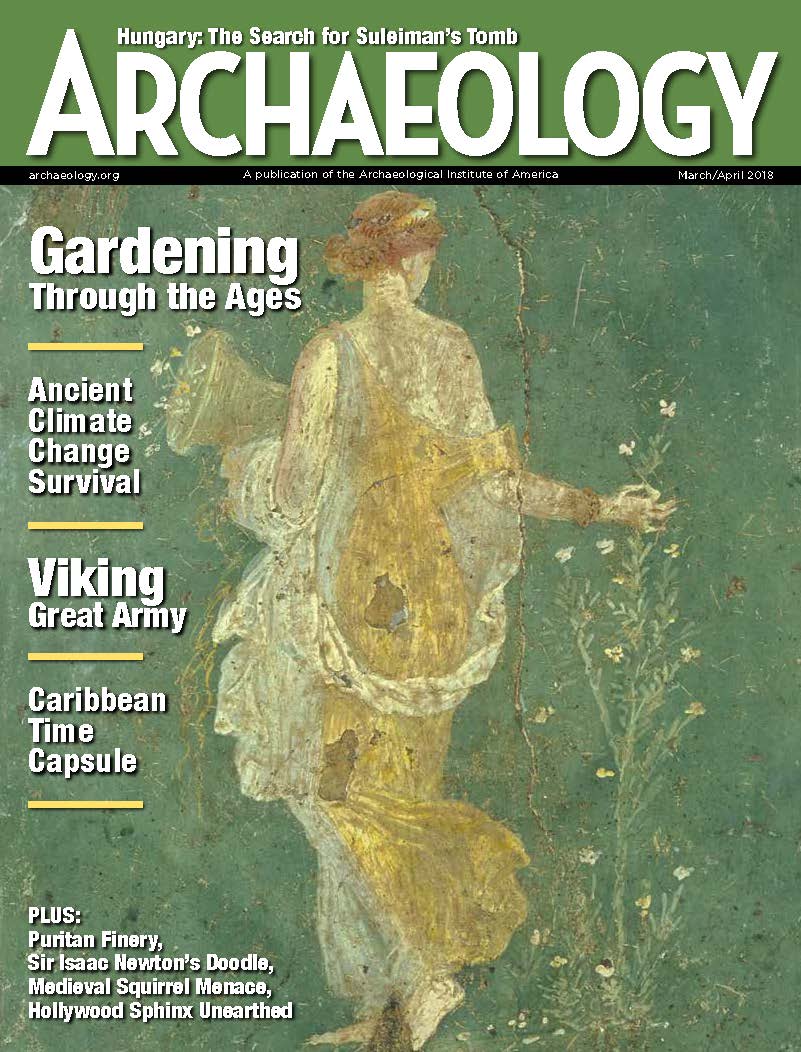

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

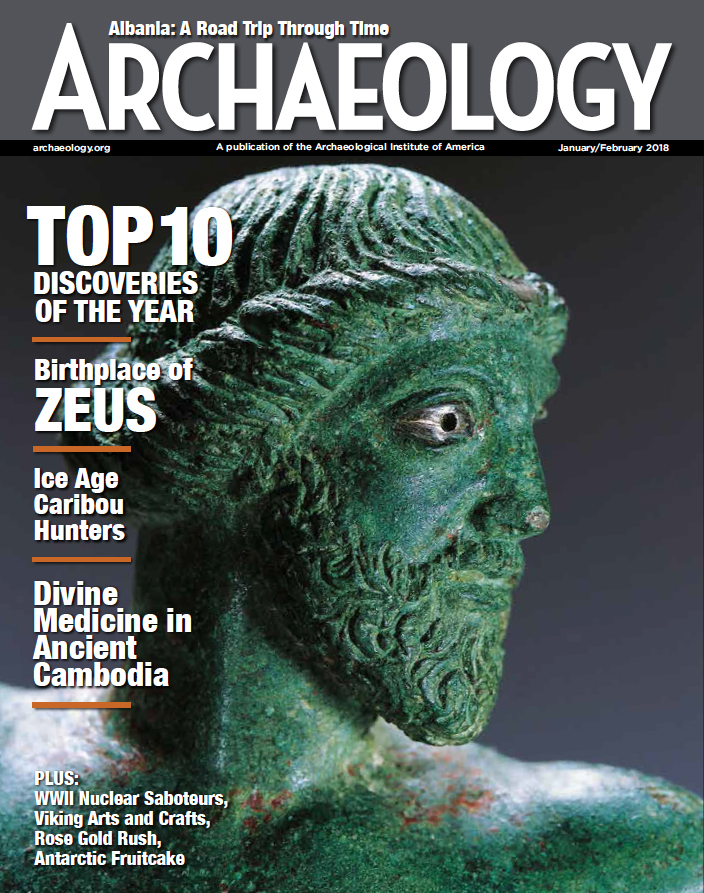

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

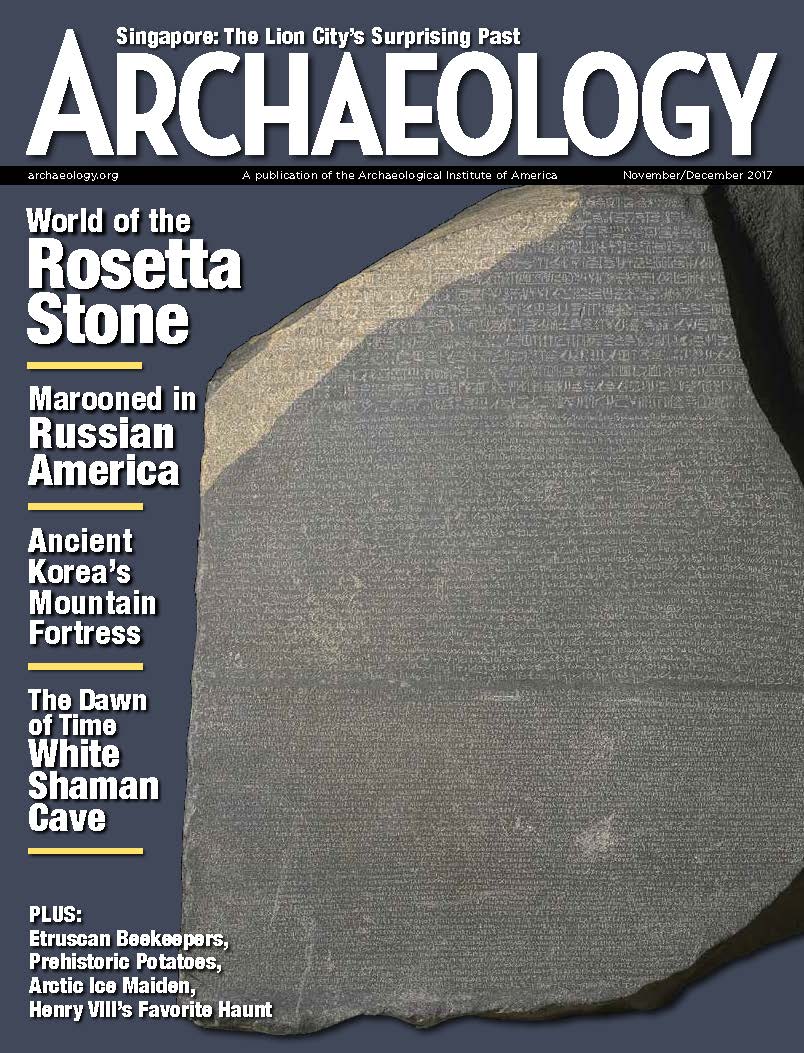

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

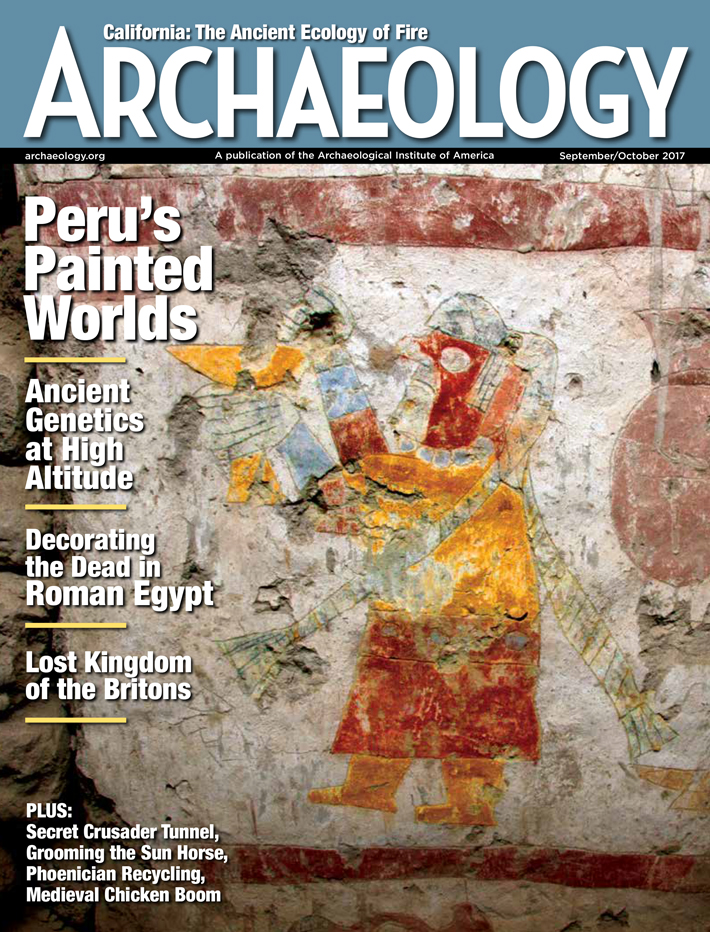

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

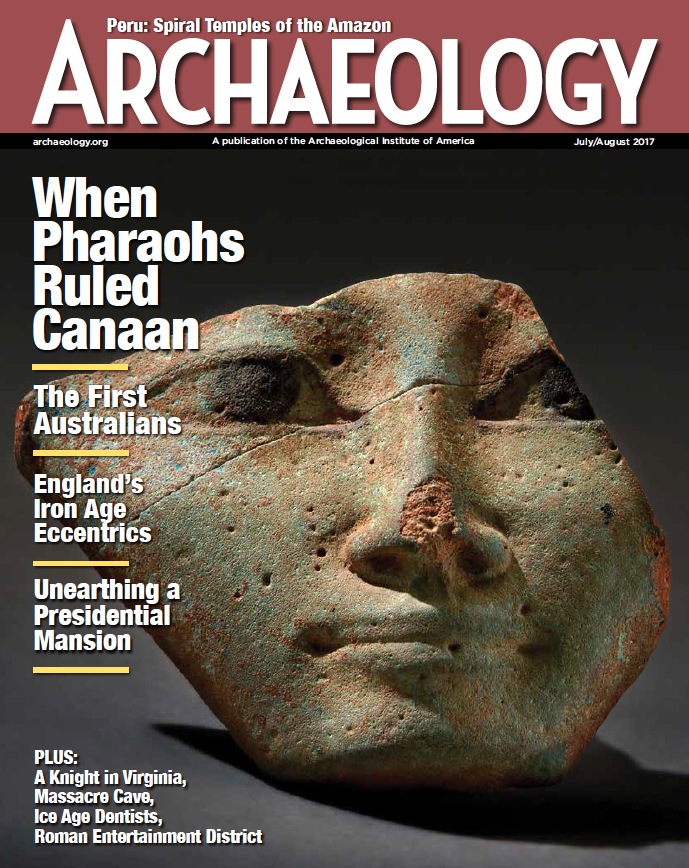

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

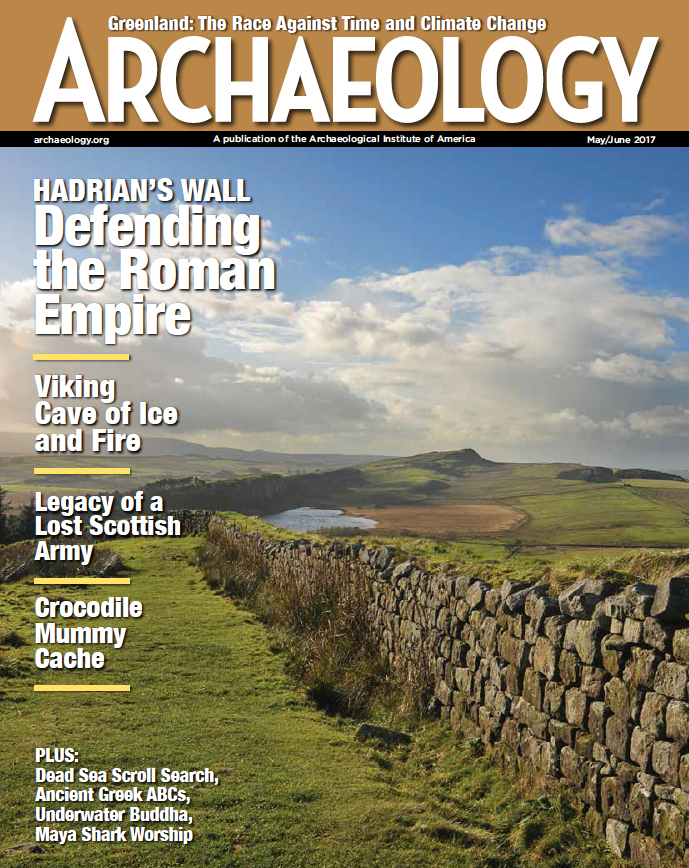

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

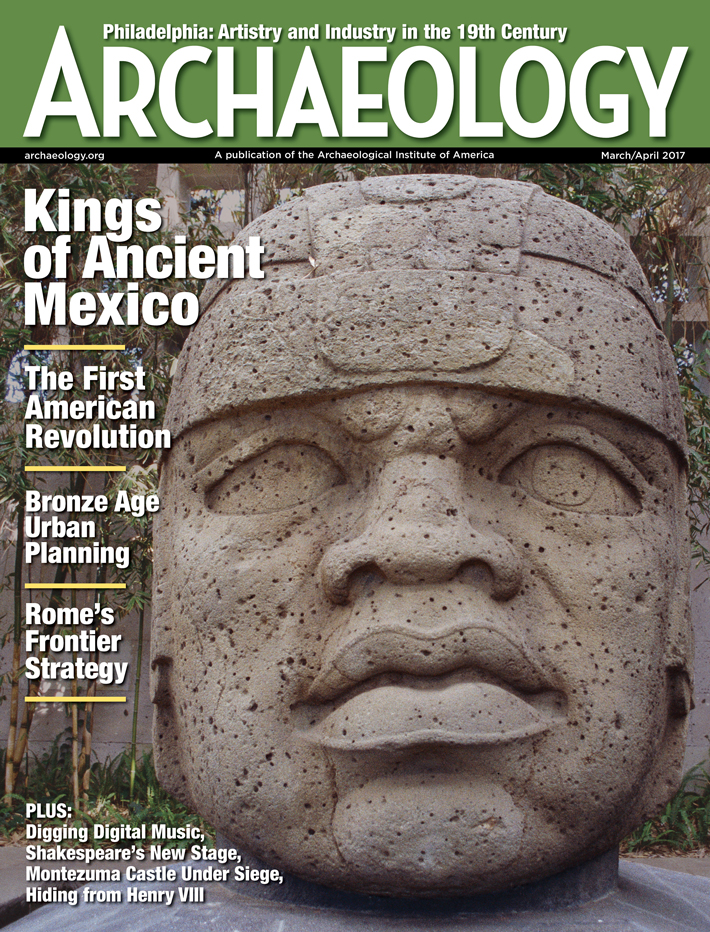

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

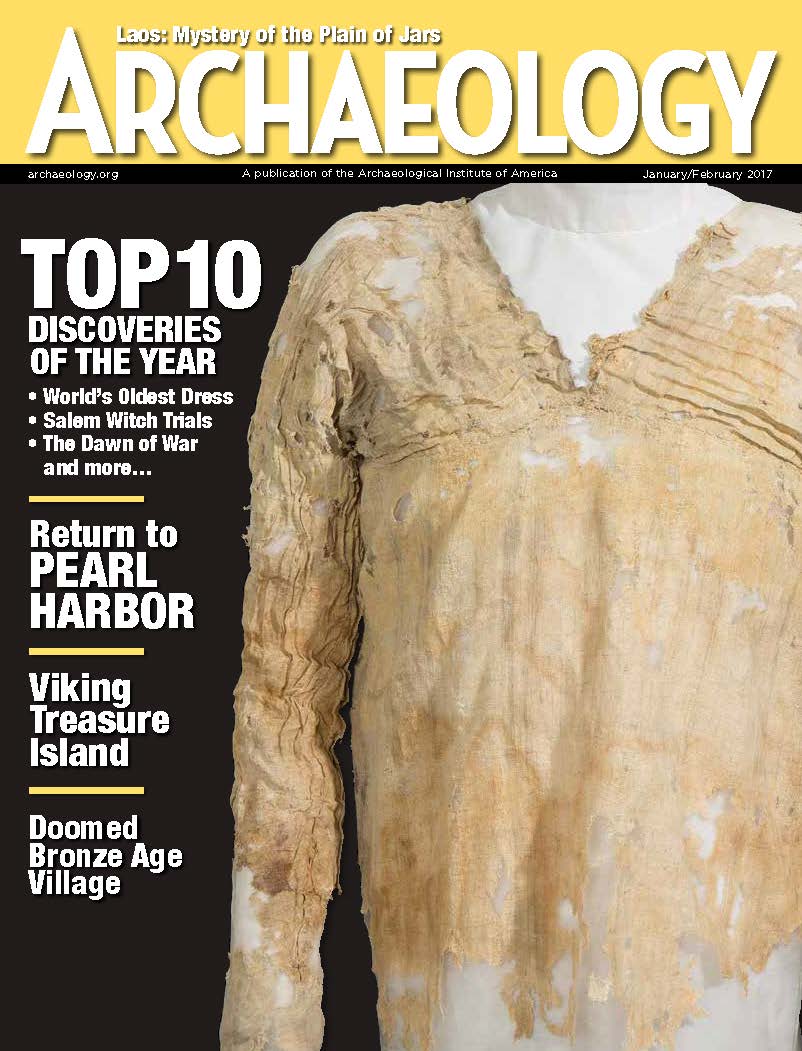

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

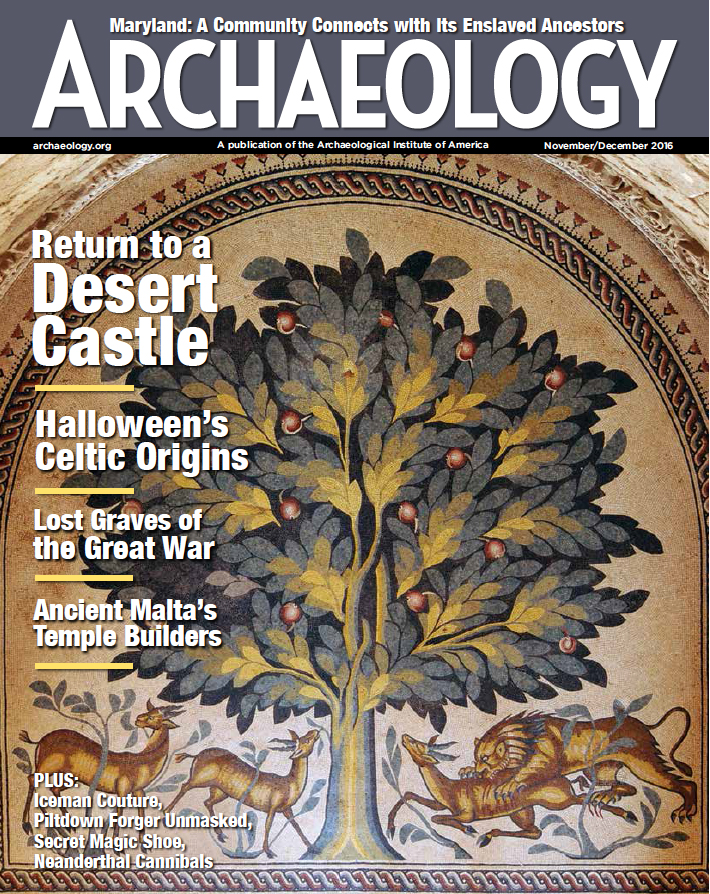

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

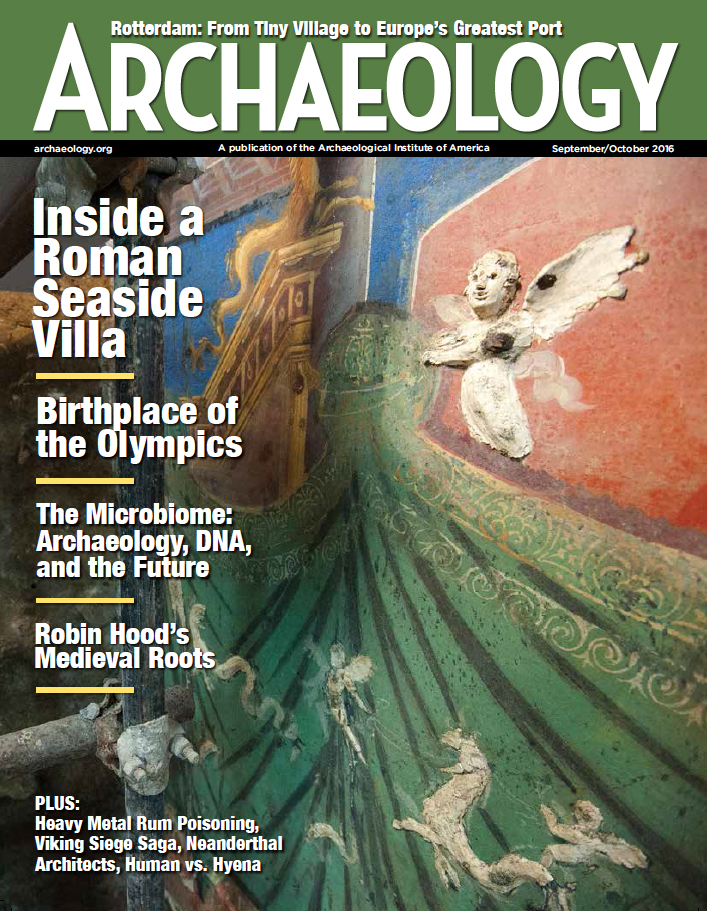

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

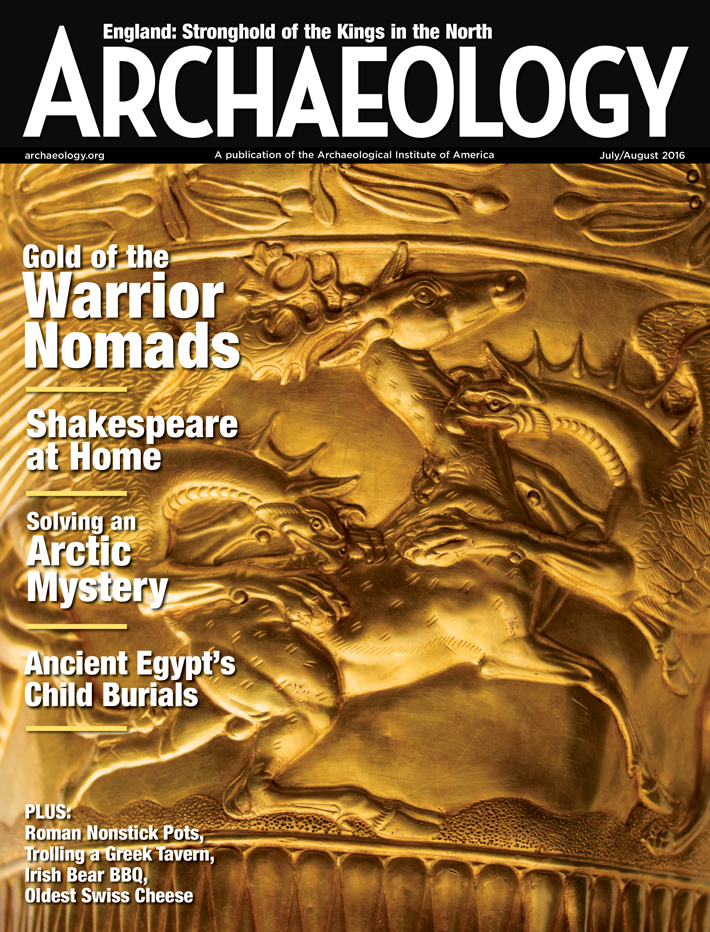

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

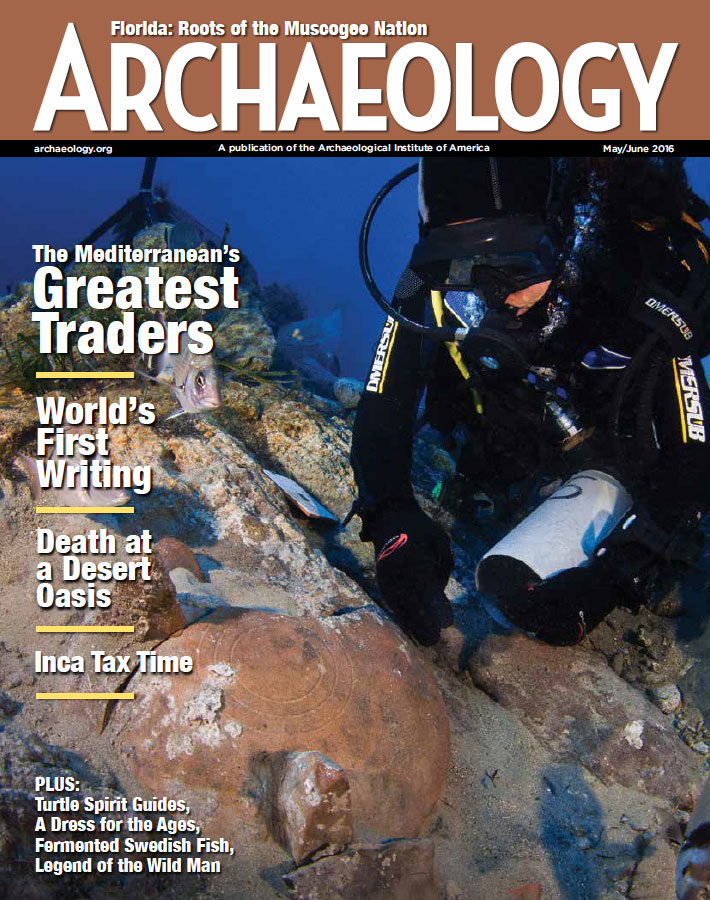

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

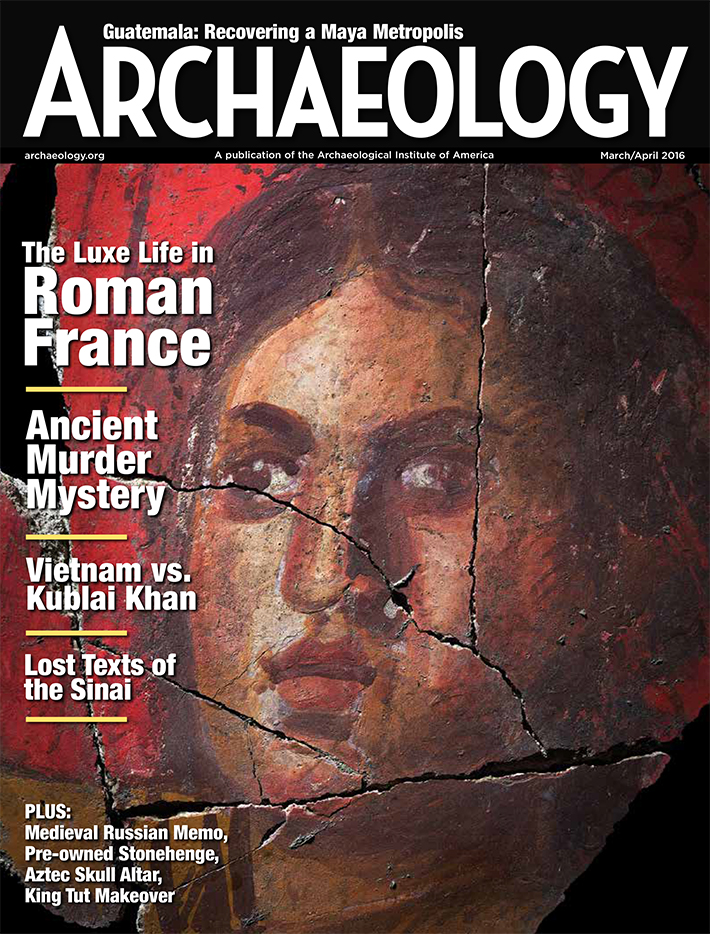

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

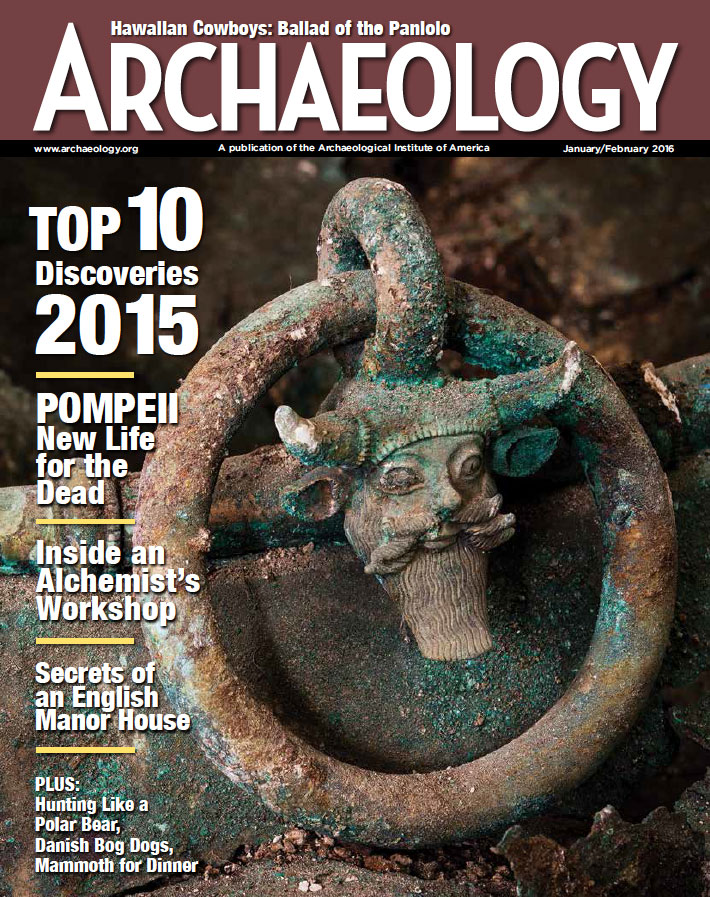

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

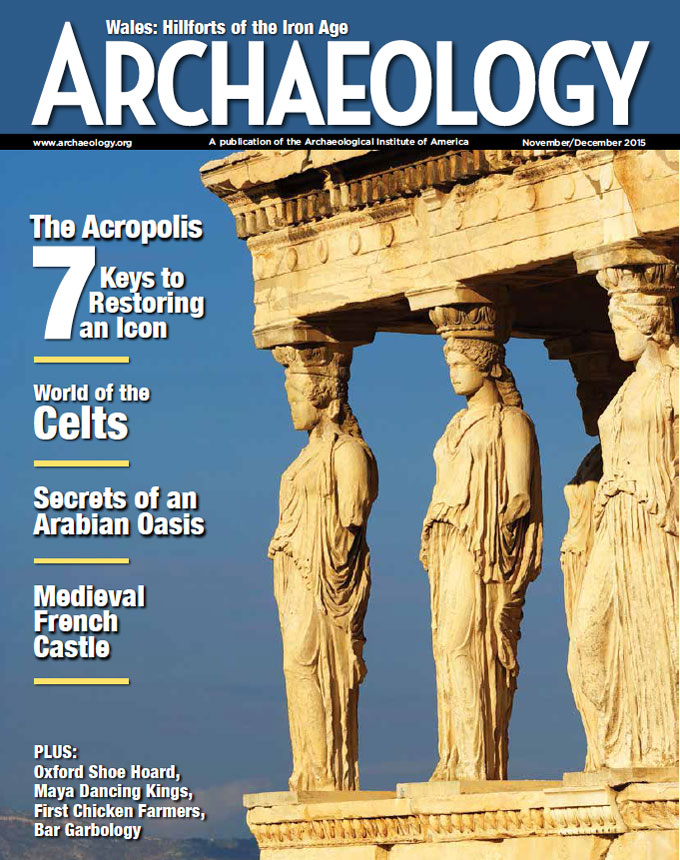

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

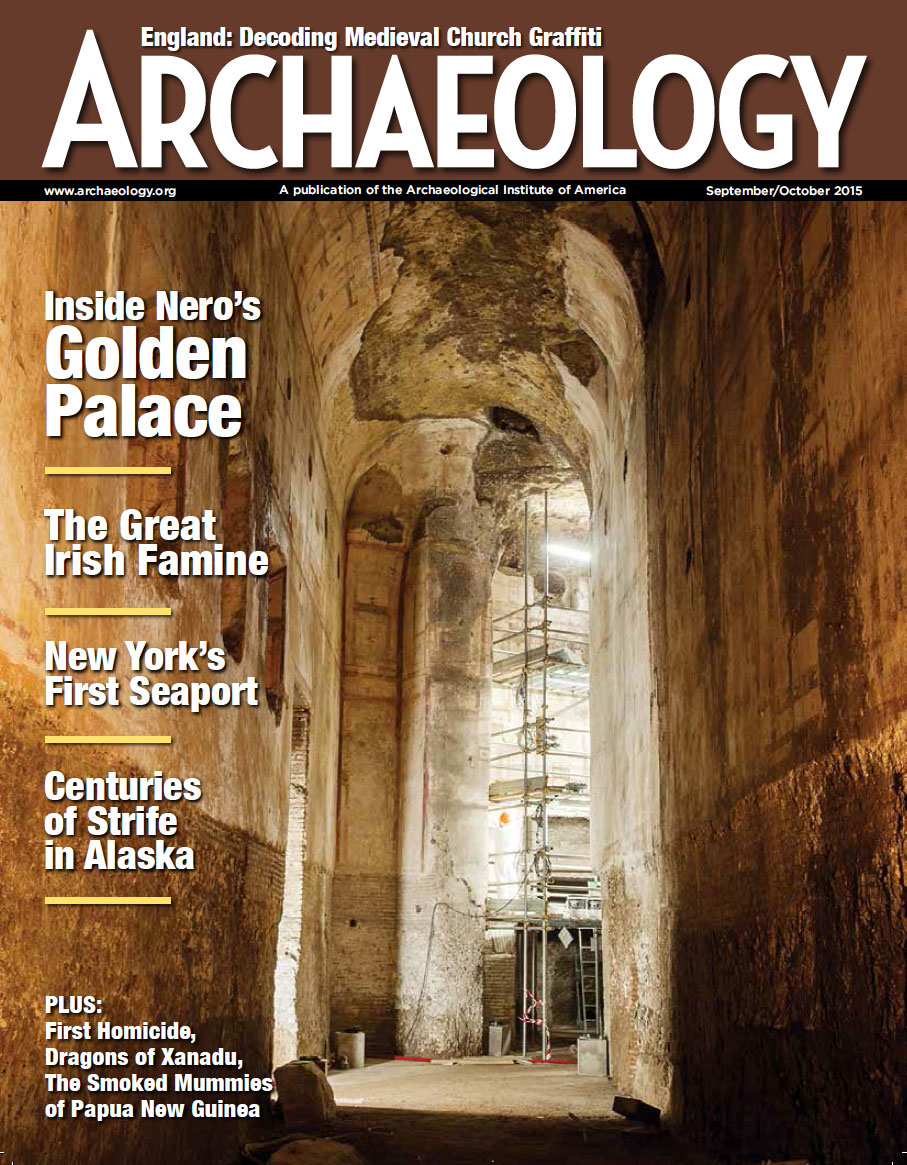

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

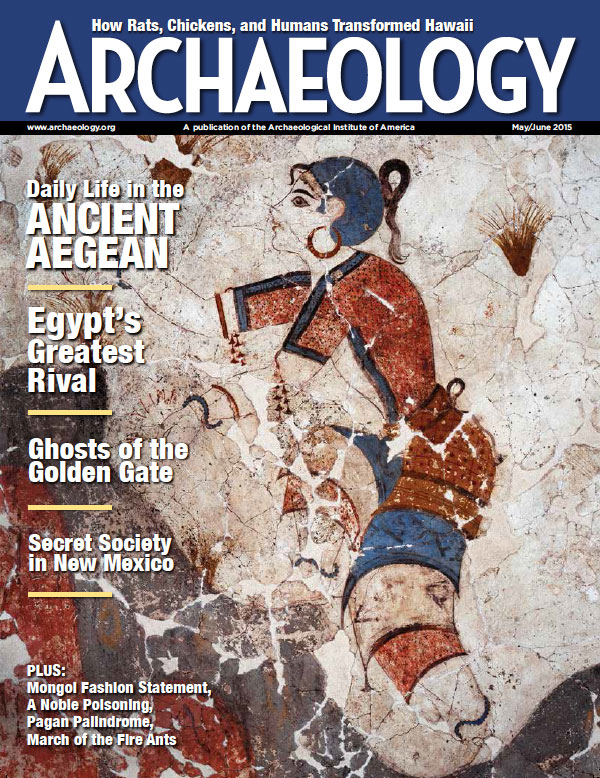

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

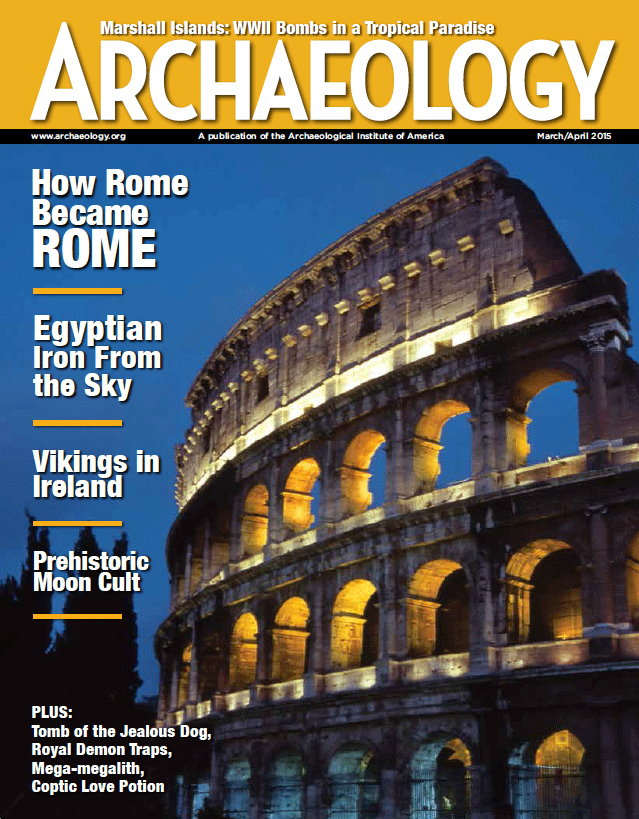

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

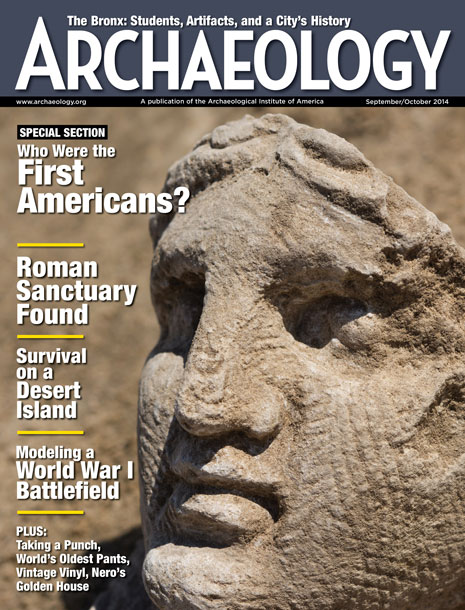

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

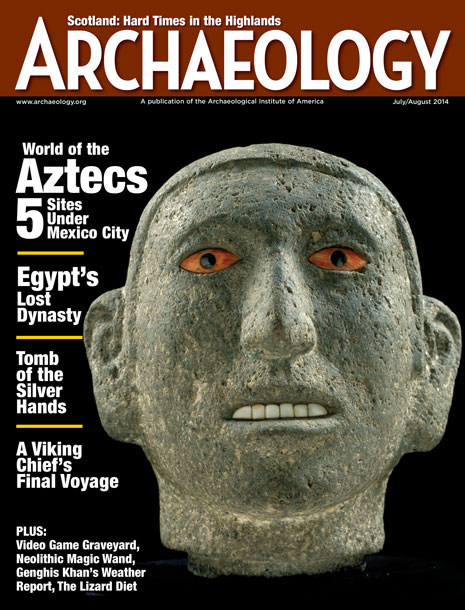

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

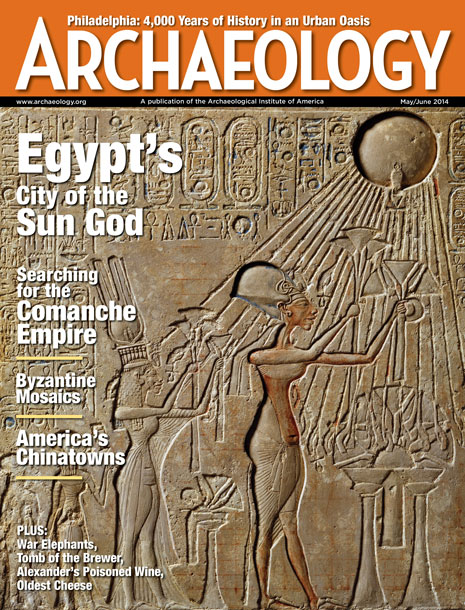

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

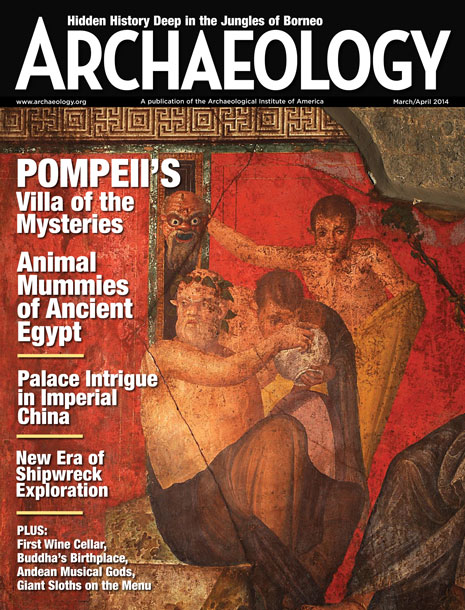

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

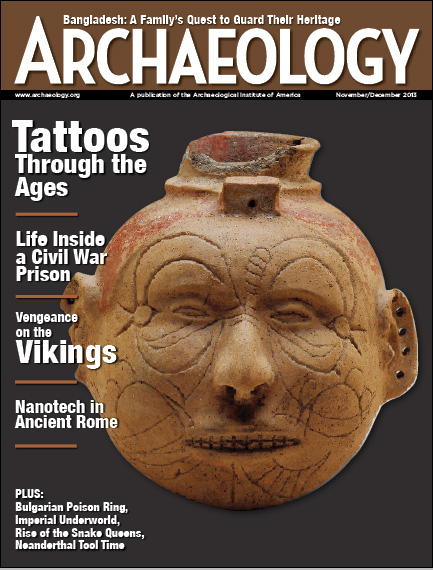

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

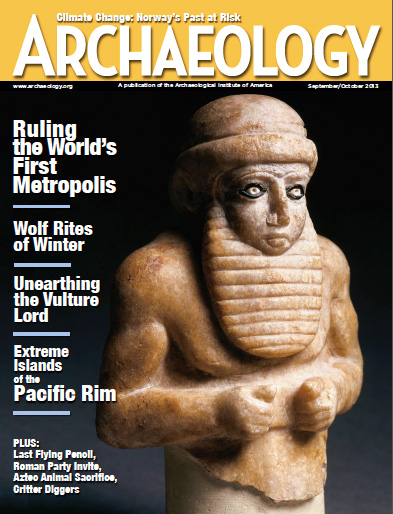

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

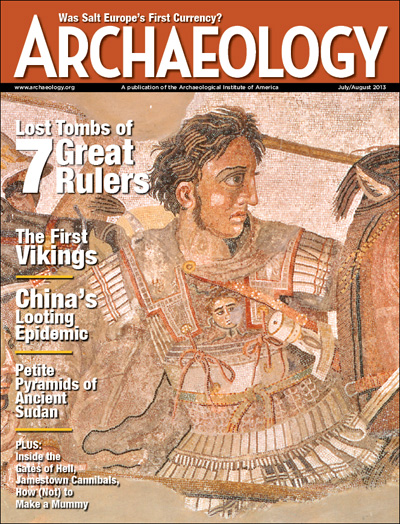

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

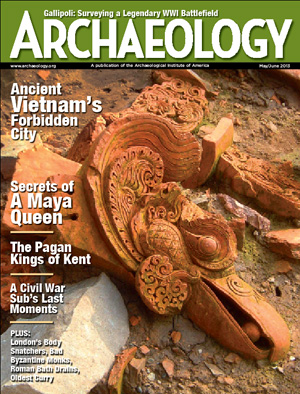

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

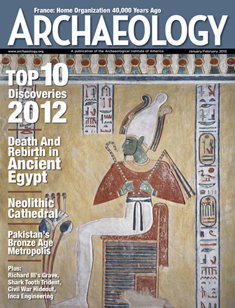

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

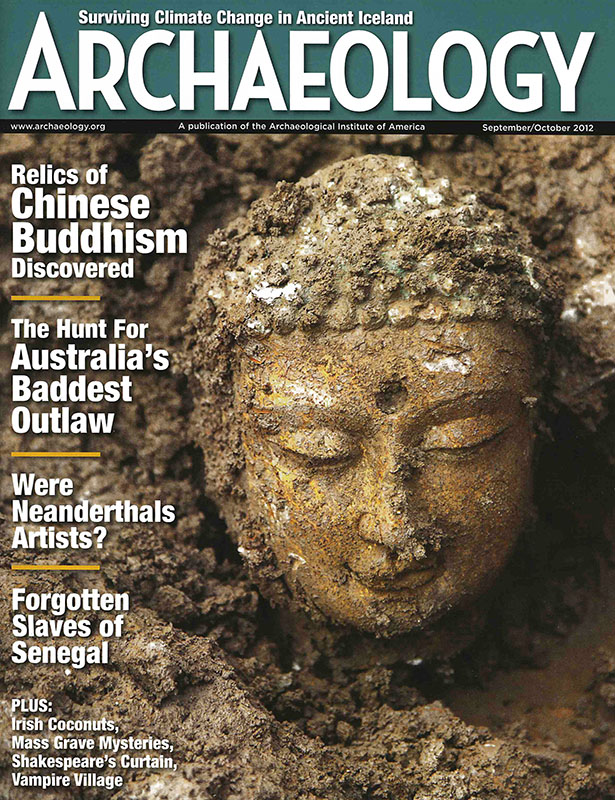

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

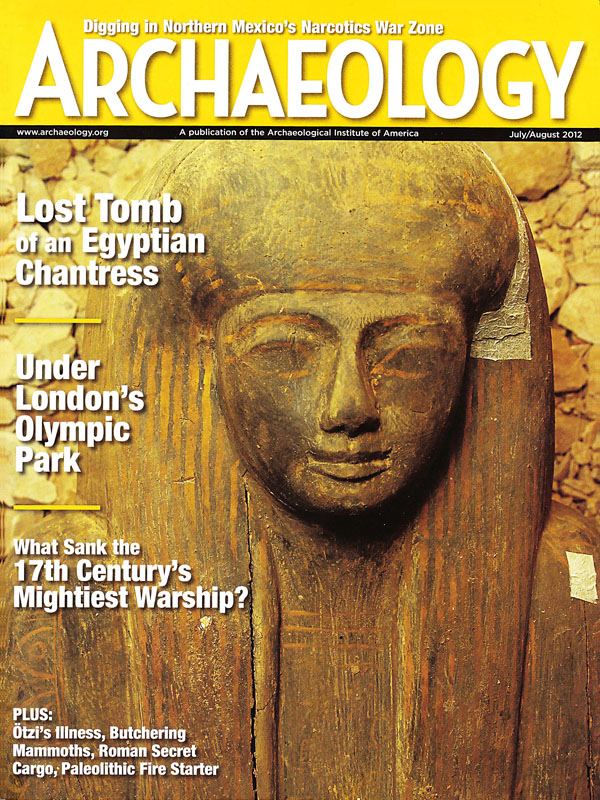

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

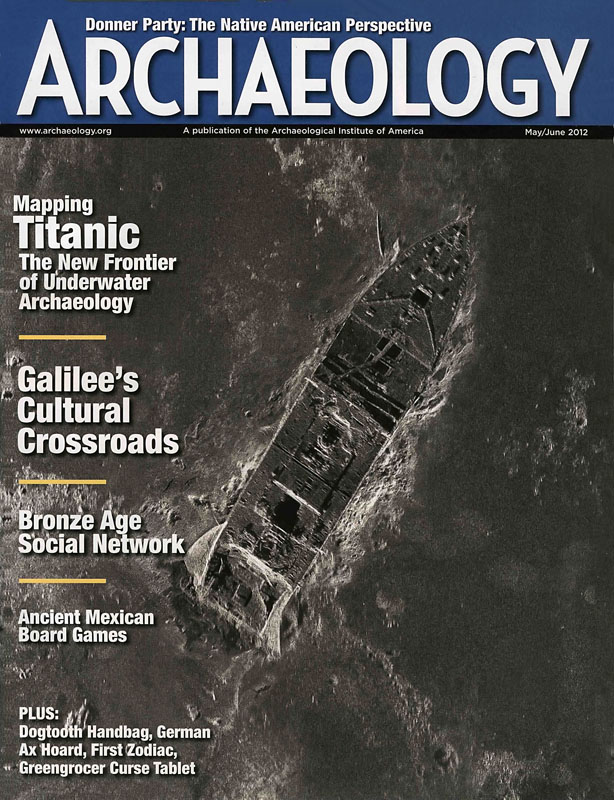

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement