In well-thumbed old books, certain pages are more thumbed—and therefore dirtier—than others. What do those pages say about reading habits? Using a device that measures the optical density of a reflective surface, Kathryn Rudy of the University of St. Andrews in Scotland asked this question of fifteenth-century personal devotional prayer books—Books of Hours—from the Netherlands. Hypothesizing that grime in the lower corners of pages would be roughly equivalent to time spent reading the page, Rudy took readings “from the juicy dirt at the bottom of the page,” she says. The most popular passages in these books tended to be prayers related to indulgences (time off in purgatory for forgiven sins) and health benefits, such as protection from plague or St. Anthony’s fire. Self-interest was the most common theme. In one manuscript that had been enhanced with custom illuminations, the owner primarily looked at pictures—in particular one that depicted the owner himself. “He really loved that image,” says Rudy.

Medieval Reading Habits

SHARE:

Recommended Articles

Digs & Discoveries July/August 2023

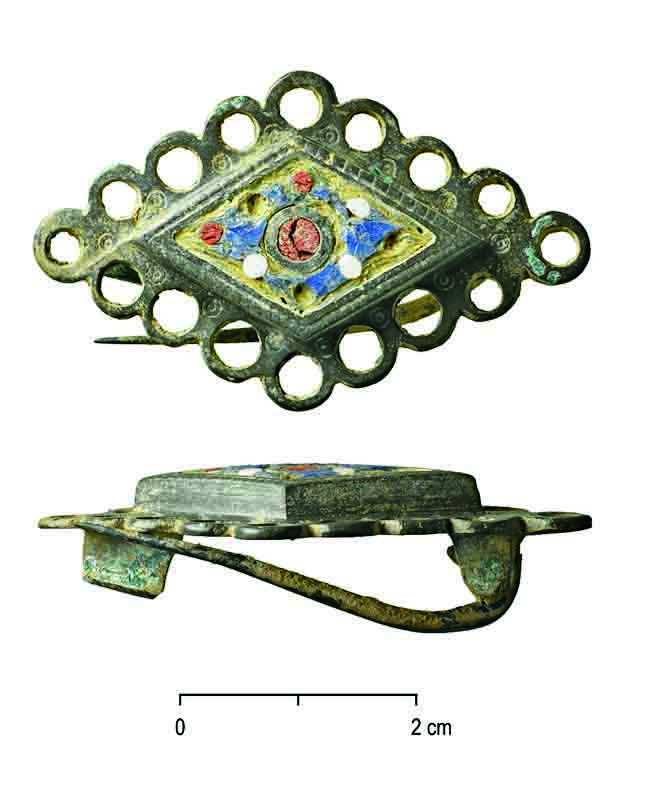

Hybrid Hoard

(Photo © Archeologie West-Friesland/Fleur Schinning)

Features July/August 2023

An Elegant Enigma

The luxurious possessions of a seventeenth-century woman continue to intrigue researchers a decade after they were retrieved from a shipwreck

(Courtesy Museum Kaapskil)

Digs & Discoveries September/October 2022

Romans Go Dutch

(Courtesy RAAP Archaeological Consultancy)

Digs & Discoveries July/August 2021

Return to Sender

(Courtesy the Unlocking History Research Group archive)

-

-

Letter from Iceland September/October 2012

Surviving the Little Ice Age

How a flexible economy saved a nation during a period of unpredictable climate

-

Artifacts September/October 2012

Inscribed Clay Tablet

A previously unknown ancient language is discovered on a 2,700-year-old tablet

(Courtesy Ziyaret Tepe Archaeological Project)

(Courtesy Ziyaret Tepe Archaeological Project) -

Digs & Discoveries September/October 2012

The Seeds of Inequality

Courtesy BDA-Neugebauer

Courtesy BDA-Neugebauer