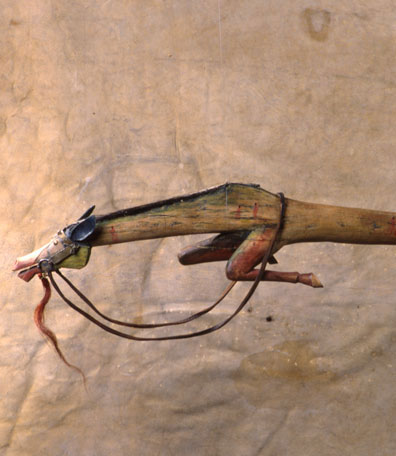

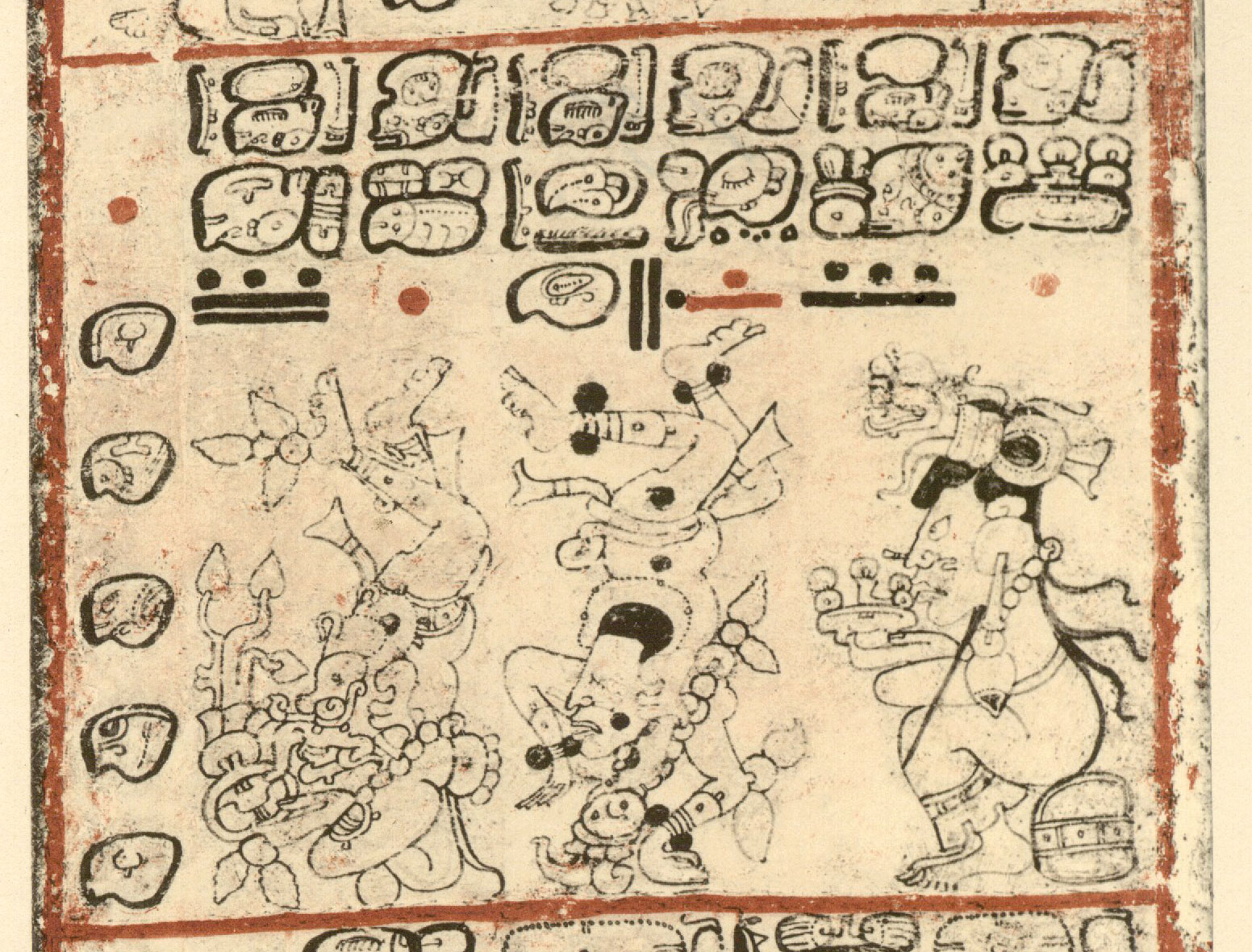

The last people to have their lives transformed by the horse were the indigenous cultures of the New World, whose ancestors had last seen the horse 9,000 years earlier. The reintroduction of the animal began in 1519, when Hernán Cortés landed in Mexico with 500 men and 15 horses. In the campaigns against the Aztecs and other Mexican nations that ensued, Cortés’ small cavalry made a critical difference. A mounted charge into the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan ended 80 days of pitched warfare there, and Cortés was never seriously challenged again.

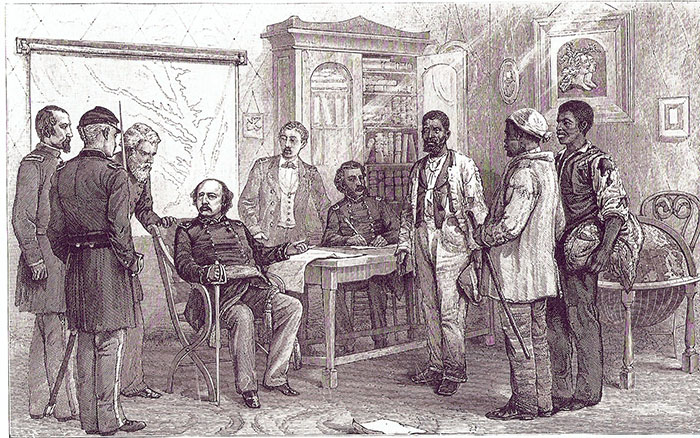

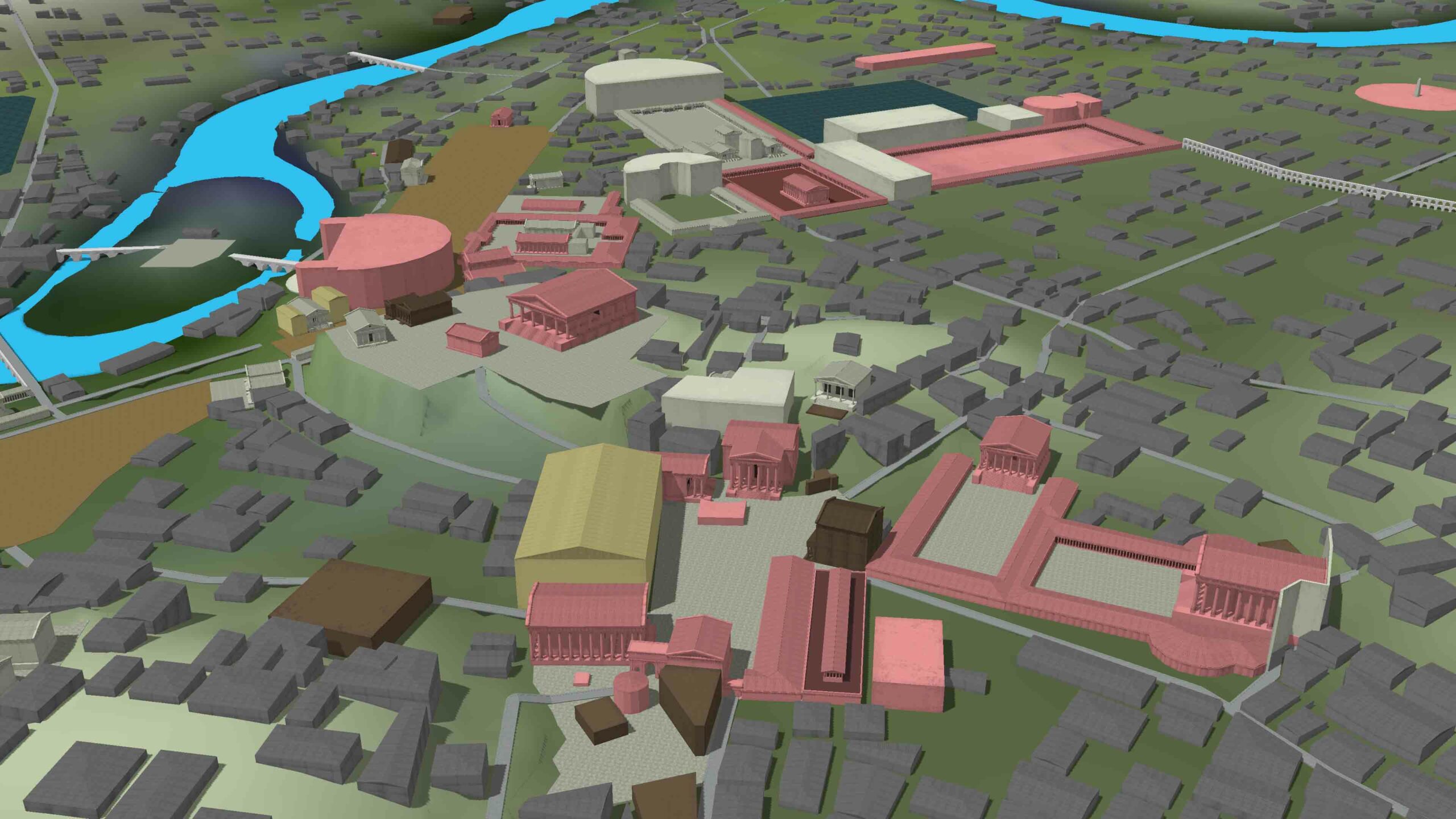

Once horses returned to the grasslands where they had originated, they helped Plains Indians reshape their culture almost overnight. Horses replaced dogs as pack animals, which enabled people to transport a great deal more goods. Enterprising riders could now chase down buffalo on horseback, and become much more efficient hunters. And some tribes, such as the Lakota, even abandoned agriculture to become full-time equestrian hunters. Increased mobility and horse raiding also led to a rise in warfare, which became endemic on the Plains. For a time, their mastery of the horse helped the Plains Indians hold off American settlers’ westward expansion, but even the best riders the world has ever seen could not challenge the massive population influx made possible by the steam locomotive, which, soon after its invention, came to be known as the “iron horse.”