Thomas W. Dyott arrived in Philadelphia from England some time around 1803 with little besides a formula for bootblack and a few shillings in his pocket—and ambitious dreams in his head. He probably lacked the credentials for it, but that didn’t stop him from setting up shop as an apothecary—the nineteenth-century equivalent of a pharmacist—at the corner of Race and Second Streets, referring to himself as “Dr. Dyott,” and assuming all the airs that went with the honorific. “He was into hyperbole for sure,” says Ingrid Wuebber, a historian with the Cultural Resources Department of the engineering firm AECOM. “And he had to have been well-spoken because people believed him and sought his advice.” It wasn’t long before Dyott put his stamp on both the pharmaceutical trade and Philadelphia history. Though he is less well remembered today, he stands alongside William Penn, Benjamin Franklin, Betsy Ross, Rocky Balboa, and the 2008 Phillies—the real, apocryphal, fictitious, and heroic characters of the city’s history.

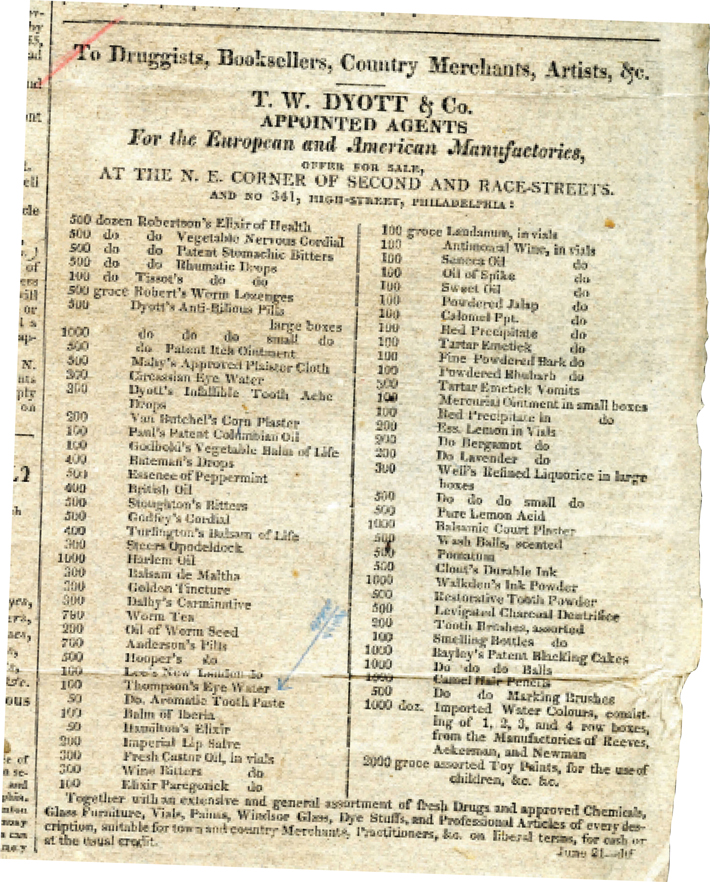

From his shop, Dyott formulated and produced a range of patent medicines, and eventually set up a distribution network across the United States. Wherever his pharmaceuticals were sold, he advertised. “He was an early ad man,” says Wuebber, who has studied what few records there are of Dyott’s life and found newspaper ads for a variety of his products. “He was an innovator and he saw [business] in an integrated way. His distribution and networking played out beyond pharmaceuticals.” Indeed, Dyott soon added glass manufacturing to his portfolio, which eliminated the need to purchase medicine bottles. Beginning around the turn of the nineteenth century, the area of present-day Kensington-Fishtown, today one of Philadelphia’s hippest neighborhoods, became a center for the glass industry. It was there that Dyott established an empire of glass, which he called Dyottville.

For about a decade, the Pennsylvania Department of Transportation (PennDOT) has been engaged in a massive redevelopment of I-95 along the Delaware River in Philadelphia, including a three-mile stretch directly north of Center City through the neighborhoods of Kensington-Fishtown, Port Richmond, and Northern Liberties. The project came with a multiyear cultural resource effort, led by PennDOT project manager Elaine Elbich and archaeologist Catherine Spohn, along with AECOM archaeologists George Cress and Douglas Mooney. “Digging I-95,” the umbrella name adopted for the excavations, findings, pop-up exhibitions, website, and more, has yielded around a million artifacts that span nearly 6,000 years of human activity, from prehistory through the Industrial Revolution to World War I. In particular, the excavations have uncovered rich nineteenth-century deposits, with an especially massive quantity of early American glass from the Dyottville Glass Works and neighborhoods nearby where many glass factory workers lived.

“The focus on Philly has always been on downtown, but what we’ve found [in these neighborhoods] are extraordinary histories,” says Mooney, who has worked on downtown digs such as the President’s House in Independence National Historical Park. “This area is better preserved, even though there has been more than 300 years of development.”

Dyott eased into glass manufacturing during the 1810s, when he became an agent for three New Jersey glass factories. Glass manufacturing had begun in northern Philadelphia in the eighteenth century, and around 1820 Dyott began to work directly with one of these factories, the Kensington Glass Works on Gunner’s Run Creek at Queen (now Richmond) Street. He took over the glassworks, which had been converted from a calico fabric printing and textile factory, in 1830. He found success with the enterprise and soon invested in neighboring properties. He eventually owned five factories, collectively renamed Dyottville. He only operated the glassworks until 1838, but it continued to produce glass under the same name, with different owners at various times, until the end of the century. Curators at the Philadelphia Museum of Art and at leading glass collections, such as the Chrysler Museum in Norfolk, Virginia, have long included flasks and bottles from Dyottville among their American glass holdings. “Dyottville has been talked about for years among collectors and others,” Cress says, “but until now there wasn’t a building [to investigate].”

The excavations at Dyottville included portions of three buildings—a glass house, a sand house, and an office/storeroom—in a space of around 9,000 square feet. It is the barest sliver of the total Dyottville site, but the only part within the I-95 right-of-way. Over 10 months, PennDOT and AECOM revealed the history of the development and expansion of the glassworks, from the foundations of the calico printing factory that preceded it, to the initial construction of the glassworks in 1816, to another building phase in the late nineteenth century. “When we excavated the factory site, we saw at least three layers of change,” Cress says. “The foundations were most interesting—how and where the building expanded from the calico works, how the creek bed had been filled in when it became a glassworks. There were tunnels. Some had been sealed over.” There were vaults for the spent fuel swept out of furnaces, and the wood floor of the sand house, still covered in glass-making sand. The foundations of multiple rectangular annealing ovens in particular were full of interesting material. When new ones were built, old ovens were filled with coal ash and manufacturing debris—thousands of fragments of glass, which were useful for dating parts of the factory, Cress says. Of more than 160,000 artifacts recovered at Dyottville, more than 140,000 are glass. Most are drips, drops, and shards, but there are also many pieces of bottles and flasks decorated with portraits.

Perhaps most unexpected of all—and now most prized among the glass factory artifacts—were the half-dozen or so complete and partial wooden block molds discovered outside a tunnel used for cleaning out furnaces. “You never find these,” Cress says, because they disintegrate quickly if they are not kept wet. “But the water level is high there.” A block mold, which aided in preforming molten glass before blowing and manipulating it into its final shape, was usually made of a hardwood such as cherry or other tight-grained fruit wood. Keeping the mold wet kept the wood from igniting and created a layer of steam to keep the glass from sticking to the mold. “We’ve never seen a nineteenth-century block mold from an archaeological site,” says Mary Mills, historic glass specialist for AECOM. “It was so amazing to find them intact.”

Not many specifics of Dyott’s life are known, but experts on the Digging I-95 project have sought out archives and other records to learn more. Research is ongoing, and new information about Dyott and the community he established continues to emerge. In 1830, Dyott set up his newly arrived brother Michael as superintendent of the glassworks, and the “doctor” turned his attention to a grander scheme. He had acquired or leased around 350 acres to make his entire operation self-sufficient agriculturally, domestically—and morally. He began to expand the Dyottville community, with a strong emphasis on creating a proper moral environment for his workers, in particular the factory’s young apprentices. The complex eventually included a 300-acre farm and some 50 buildings, among them a chapel, an infirmary, homes for married employees (often entire families worked in the business), and dormitories for single men and women. Field workers, butchers, bakers, cooks, carpenters, blacksmiths, laundresses, and teachers were all on the payroll. “He encouraged workers to take up a hobby, music, or sports,” says Mooney. Those who signed a contract to live in Dyottville agreed to certain rules, including regular attendance at Methodist services. “And no cussing, no drinking,” Mooney adds. The regulations were spelled out in a 39-page pamphlet published in 1833, “An Exposition of the System of Moral and Mental Labor, Established at the Glass Factory of Dyottville.”

Dyott’s experiment in welfare capitalism remains buried under private land near the site, but the full scope of the I-95 excavations includes a number of working-class neighborhoods, with full privies packed with household trash, providing glimpses into the lives of the glassworkers, fishermen, and shipwrights who lived there. Archaeologists and other experts say that the great amount of glass found in the privies and elsewhere—“a concentration of glass like I haven’t seen anywhere,” says Cress—tells us a great deal about the artisan skill, home life, values, and cultural development of a neighborhood strongly shaped by glassmaking. It represents new knowledge about the history of one of America’s oldest cities. “This was a working-class neighborhood,” says Mooney. “And we have found a great density of objects from their homes, both stuff that was made right here and imported wares.

“You don’t usually get to excavate a glassworks and the homes of people who worked in glass factories and [those of] their neighbors,” adds AECOM senior research analyst Rebecca White. Mills explains, “What has made this dig so important is not just the factory, but where people lived. Understanding how this community differed [from others] does have to do with the amount of glass. But also with the whimsies.

Whimsies? Glassblowers worked their way up through an apprenticeship system, often starting in boyhood with tasks such as carrying coal and weaving wicker wrappers for large bottles. A master blower, or gaffer, would have developed the skills and dexterity to control and manipulate very thin blown glass. It took plenty of stamina to work in the constant heat of a furnace to produce vases, pitchers, and flasks, but at day’s end workers used their leftover time and materials to make “whimsies”—exquisite, often fragile, personal artistic pieces, or demonstrations of skill to impress factory visitors. The glass colors—aqua, amber, and green, mostly—match those used on the production line, but there was a difference between work, which was done as quickly as possible, and making whimsies, according to White. “These were things they made for each other, for family, for wives, for romanticized notions,” Mills says. Whimsies appear in the surrounding home sites, but also in the manufacturing debris in the Dyottville annealing ovens.

“We found so many ‘Jacob’s ladders’ in the Dyottville factory and throughout the neighborhood,” Mills adds. “I had never seen them before.” They were made by wrapping a thin thread of molten glass around a tool to make a delicate spiral that symbolizes the connection between Earth and heaven. Mills also notes the discovery of fragments of “flip-flops,” distinctive noisemakers consisting of a thin bubble of glass flattened on one side with a mouthpiece on the other. When one blew into the mouthpiece, the flat glass vibrated, making a loud popping or cracking sound. “These were very thin, and were blown in and out, so you had to be very skilled to make them,” she says.

Glass canes, another kind of whimsy, have been found in different sizes and styles, usually in bright colors. Few are alike. Sometimes these nonfunctional canes were given to visiting dignitaries, while others were take-home amusements. Then there are glass top hats, some full size, and witch balls, or blown-glass spheres in a variety of colors and sizes. Domesticating and keeping birds rose in popularity during the nineteenth century, and bird fountains, elaborate and plain, functional and decorative, have turned up as well. “Within three blocks of Dyottville, we’ve found mugs, pitchers…so much else that workers made for themselves,” says White. All of the whimsies, beautiful creations, fun things, and individual expressions, functional or not, personalized these working-class homes.

The artistic glass items weren’t exactly part of Dyott’s outsize vision and ambition—he had a keener eye for making money than for art, perhaps a little too keen in the end. Dyottville seems to have been humming along until Dyott devised a bank scheme that went bad and landed him in Eastern State Penitentiary in Philadelphia, and put the glassworks in a sheriff’s sale. His social experiment had lasted less than a decade and sputtered to a close in 1837. But the factory reopened, and the Dyottville name reemerged, rather unscathed, a few years later under new ownership. Gradually the glass industry in Kensington-Fishtown declined, and today there’s little sign aboveground that it was ever there. Dyott, after serving his sentence for fraud, returned to the streets of Philadelphia not as a property owner and manufacturing magnate, but once again as an apothecary.