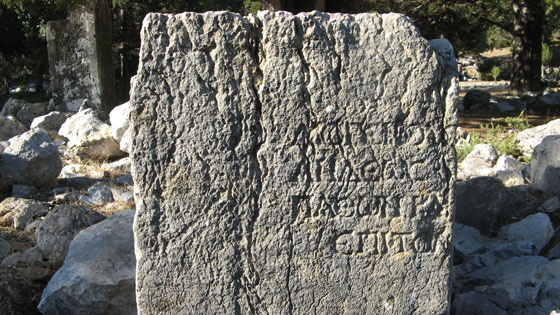

In the winter of 1884, two young French epigraphers were exploring the ancient Greco-Roman town of Oinoanda in southwestern Turkey and made an intriguing discovery. Scattered in the well-preserved ruins on a hilltop covered in cedar trees, they found five stone fragments inscribed with writings of a then-unknown philosopher, Diogenes of Oinoanda. On one of the fragments, Diogenes explains why he committed his thoughts to stone:

The majority of people suffer from a common disease, as in a plague, with their false notions about things, and their number is increasing. ...I wished to use this stoa to advertise publicly the [medicines] that bring salvation.

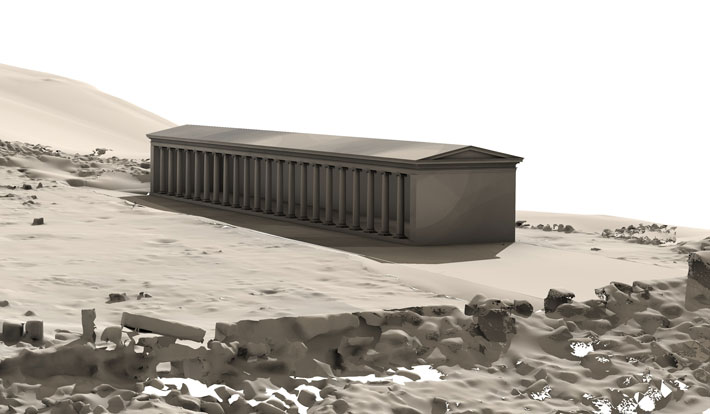

The “medicines” Diogenes hoped to use to cure the “disease” of false understanding was Epicureanism, a system of philosophy founded in the fourth century B.C. by the Greek philosopher Epicurus. It was grounded in physics, held that the pursuit of pleasure is the highest good, and eschewed belief in divine intervention. The wealthy Diogenes had paid for the inscription to be carved on the wall of a stoa, or covered walkway, that probably once stood in one of the town’s public squares. He makes plain that he hoped Oinoandans and visitors alike would make a close study of his words and come away converts to the Epicurean school of thought. After the discovery of the five fragments was published and their significance understood, French and Austrian archaeological teams visited Oinoanda between 1885 and 1895. They recovered another 83 fragments of the inscription, which remains the only ancient philosophical text from the Greek and Roman world to have survived in its original form.

As interpretive work on the inscription continued in the first half of the twentieth century, Diogenes came to be seen as a not particularly deft exponent of Epicureanism. Perhaps as a result, there was no concerted effort to search for new fragments of his inscription until 1968, when the British classicist Martin Ferguson Smith, now professor emeritus at Durham University, made a pilgrimage to the site some have called an “epigraphic El Dorado.” Smith had just completed a translation of the first-century B.C. Roman writer Lucretius’ On the Nature of Things, a philosophical poem that explores Epicurean philosophy and whose rediscovery in the fifteenth century some scholars credit with helping usher in the Renaissance.

For Smith, the lure of as-yet-undiscovered fragments of Diogenes’ inscription—further writings on Epicureanism—was irresistible. Initially on his own, and then under the aegis of the British Institute of Archaeology at Ankara, he spent many years working at Oinoanda. He documented both known and newly discovered fragments by using a brush to push moistened filter paper into the indentations on the stones, which, after drying, created a permanent impression of the lettering. Smith’s intensive study of the fragments and his discovery of other texts at Oinoanda, including an inscription describing the founding of a musical festival at the city, allowed him to tentatively date Diogenes’ inscription to the early second century A.D. Additionally, he hypothesized that the wall carrying the inscription was perhaps destroyed by an earthquake, or more likely deliberately torn down in later antiquity, when Christianity began to hold sway and Epicurean ideas were viewed with some hostility. Over time, many of the stone blocks containing the inscription were used in new construction, hiding the inscription from sight.

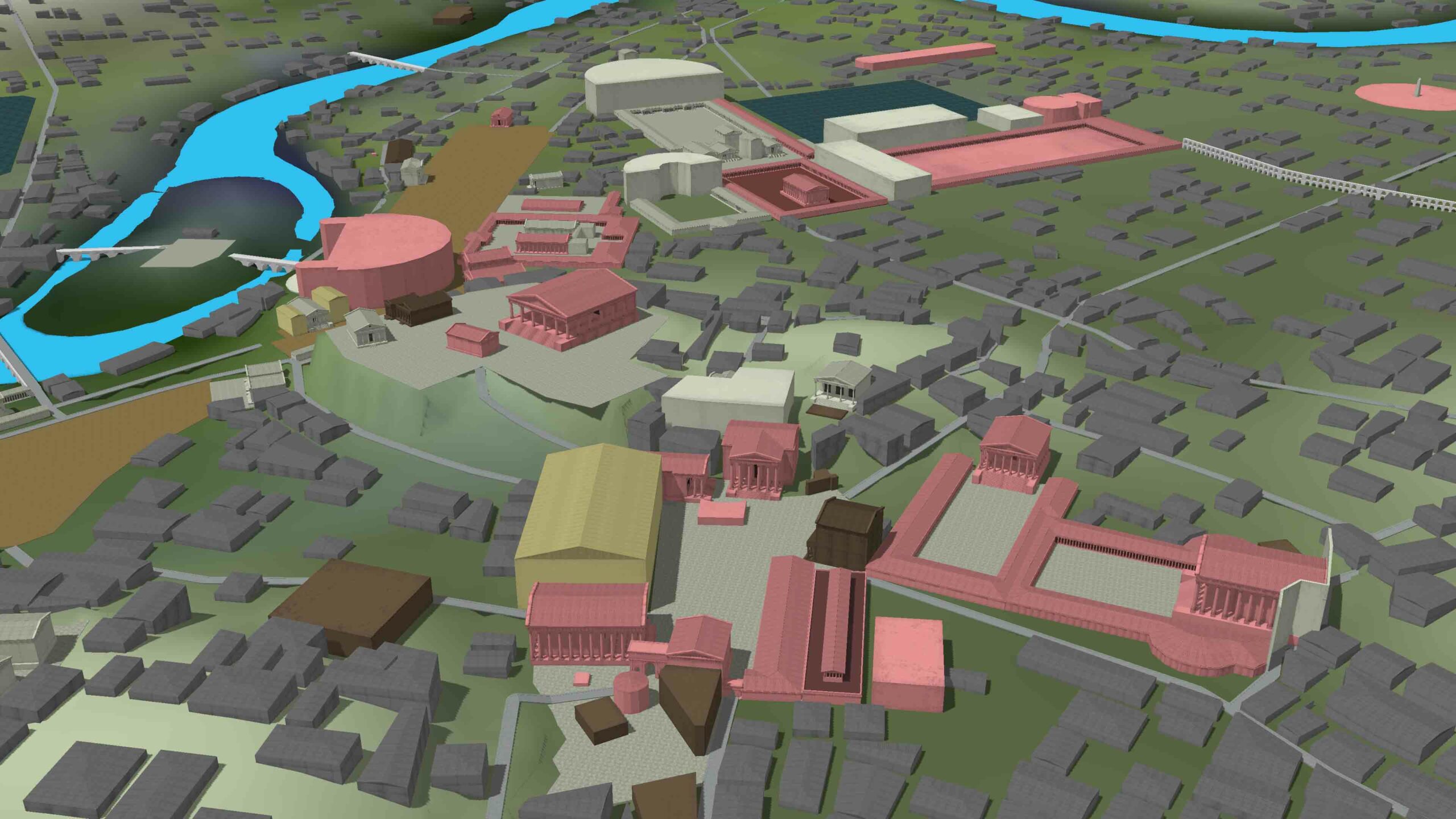

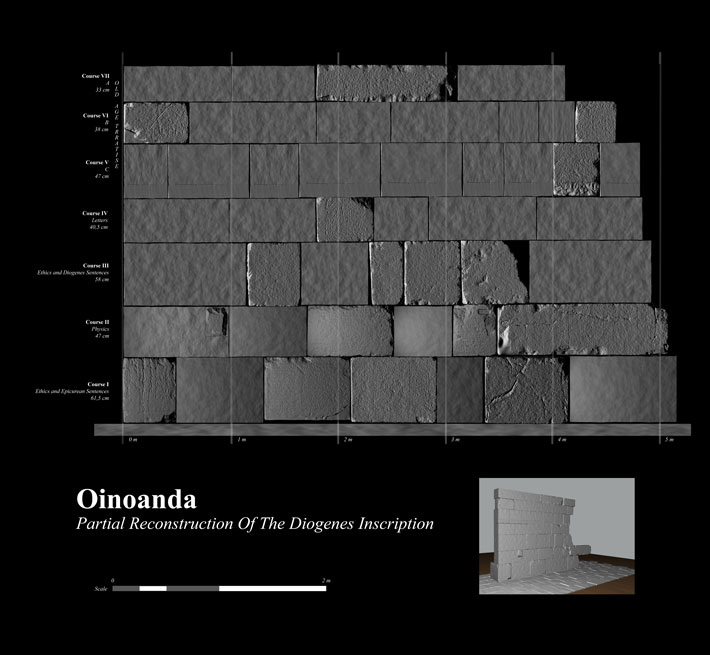

Smith also proposed that the inscription was originally divided into seven distinct rows, with the bottom row containing Diogenes’ writings on ethics and quotations from Epicurus’ own works on the subject. Above that would have been a row inscribed with works on physics, an important theme in Epicureanism, which holds that matter is neither created nor destroyed, but is made up of indestructible atoms. Above this row, another explored ethics and recorded maxims probably composed by Diogenes himself. A fourth row contained the letters of Diogenes, and above that, a lengthy treatise on old age took up three additional rows. Smith hypothesized that the inscribed stoa wall once stood 12 feet tall, stretched more than 200 feet, and might have contained some 25,000 words. Smith’s work on the inscription led to a 1997 limited excavation of the town square where the stoa likely stood. His team dug only three small trenches, but still managed to uncover eight large fragments of the inscription that had been repurposed as pavement supporting statue bases. In these fragments, together making up the longest segment of the inscription to be discovered, Diogenes argues that the gods are indifferent to human affairs, and criticizes the Stoics, a rival philosophical school.

In all, Smith found 136 previously unknown fragments, including one that was dubbed the “Golden Age” fragment. In it, Diogenes looks forward to a time when many people would have converted to Epicureanism. “He says that all will be peace and harmony,” says Smith. “There will be no wars, no laws, and we won’t need walls to defend us.” Smith notes with a trace of sadness that some of the inscription fragments were reused in fortifications during late antiquity, when civil wars and incursions by the Goths meant life in Oinoanda was far from a Golden Age.

Smith returned to Oinoanda in 2007, this time as part of a team sponsored by the German Archaeological Institute. Led by archaeologist Martin Bachmann of the Institute’s Istanbul Department, the group included University of Cologne philologist Jürgen Hammerstaedt, who worked closely with Smith to translate and interpret the inscription. The goal of the new project was to survey the entire city of Oinoanda to understand the context of the inscription, and to record the locations of known fragments with GPS and high-tech imaging techniques.

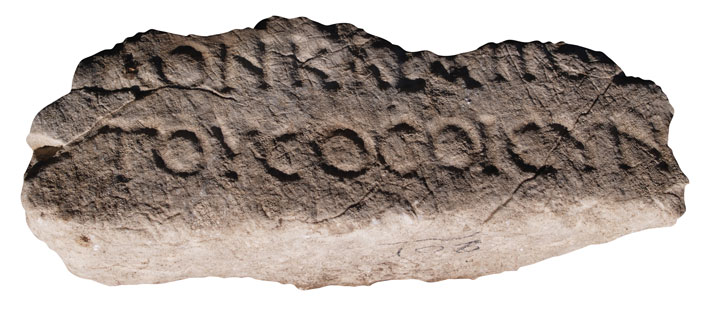

Remarkably, although the team conducted no excavation, they were able to find 75 more previously unknown fragments simply by intensively surveying the surface, bringing the total count to 299. Many of the newly discovered fragments are small and partial, but they also include some significant blocks, such as a critique of Plato’s theory of the origins of the universe and a section of a physics treatise that criticizes the idea that lightning, thunder, and earthquakes are the work of the gods. Newly discovered fragments of Diogenes’ letters also refer to a powerful family that ruled the province of Lycia (in which Oinoanda was situated) in the early second century a.d., which supports Smith’s dating of the inscription.

The team is also trying to understand how Diogenes’ wall fit into Oinoanda’s urban landscape, and how the inhabitants and visitors to the city would have interacted with and read the inscription. “One question we have is how people would have read the very top courses,” says Hammerstaedt. “The letters are bigger there, but they are still 12 feet above the floor.” He wonders if the inscription covered the stoa’s outside wall, where the light would have been better, and perhaps sloping terrain would have enabled people to get closer to the upper sections. Ongoing 3-D reconstruction of the wall, with architectural experts helping Smith and Hammerstaedt interpret how the inscriptions were arranged, may help answer the question.

There are no known parallels to the Diogenes inscription in the ancient world and no contemporary accounts of it exist. But Hammerstaedt notes that the inscription was so prominent and so unusual that it must have been known throughout Lycia and even farther abroad. One reason it was so exceptional is that, unlike members of other philosophical schools, Epicureans were intensely private, and were not known to make public speeches or assemble in public places. “Epicurean writings typically circulated among small, esoteric circles,” says Hammerstaedt. “So for Diogenes to proclaim the blessings of Epicureanism in such a public forum is very unusual. It’s almost the equivalent of modern-day open-source publication.”

Smith notes that some classicists have derided Diogenes as “an intellectual weakling and a philosophical ignoramus.” However, he believes it’s important to remember that he was not writing for fellow philosophers, but rather for ordinary people on the street, hoping to persuade them of the virtues of Epicureanism and offer them a way of improving their lives.

With its survey work now complete, the team is focused on creating the virtual, 3-D reconstruction of the inscription based on the known fragments, many of which are now stored in a secure warehouse at the site. And while there are no concrete plans for excavation, any future expedition will have the benefit of extraordinarily detailed maps of the site made by Bachmann and his team. For their part, Smith and Hammerstaedt are anxious to know what still lies beneath the earth at Oinoanda. Hammerstaedt believes that 75 to 80 percent of the inscription could remain underground or have been recycled as part of other buildings at the site. He is especially interested in the potential for discovering more of Diogenes’ personal letters, which could shed additional light on the philosopher himself. “After all, he was a remarkable man and a cosmopolitan man,” says Hammerstaedt, who recites a favorite quote from Smith’s translation of a passage in which Diogenes declares that he set up the inscription:

Not least for those who are called foreigners, for they are not foreigners. For, while the various segments of the Earth give different people a different country, the whole compass of this world gives all people a single country, the entire Earth, and a single home, the world.

Slideshow: Translating a Lost Philosopher

In 1968, epigrapher Martin Ferguson Smith began to document what is considered the ancient world’s most massive inscription. Located in the ancient Greek city of Oinoanda in southwestern Turkey, the 200-foot-long wall, now largely in ruins, was the work of a little-known second-century A.D. philosopher, Diogenes, who paid to have it inscribed with his commentary on Epicurean philosophy. As of now, there are 299 known fragments of the inscription. Below are images of some of those fragments, along with Smith's translations of the words that appear on them.