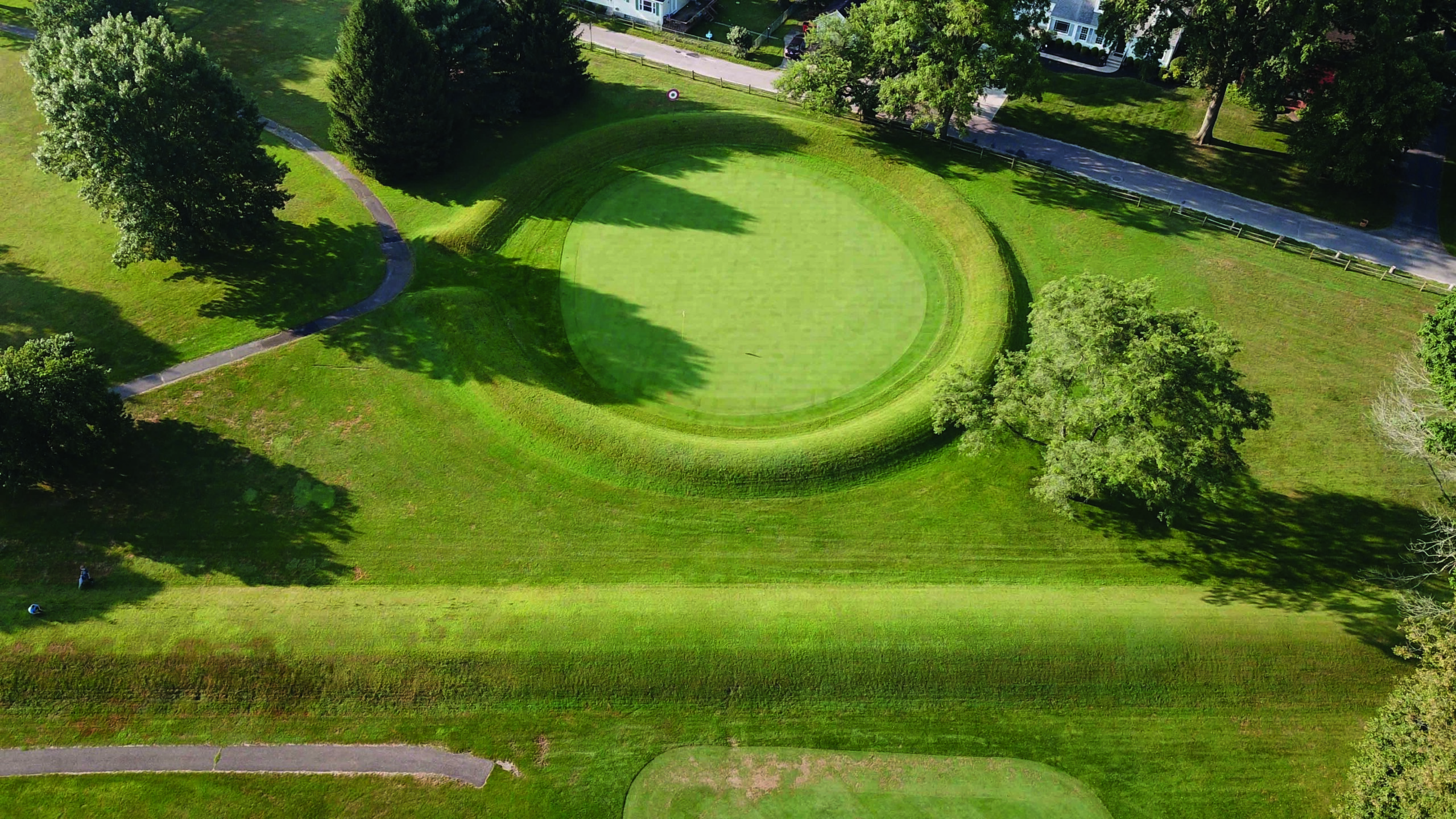

As visitors to Persepolis, capital of the Persian Achaemenid Empire, entered the city, they would approach a stone terrace on which a palatial precinct rose 40 feet above the fertile flatlands at the foot of Kuh-i-Rahmat, the Mountain of Mercy. Bearing gifts from their homelands—perhaps a metal chalice or a braying donkey—they would ascend 63 limestone steps, pivot on a landing, then climb another 48 steps to an imposing threshold known since antiquity as the Gate of All Nations. Flanking the four-story-tall gate were statues of lamassu, winged bulls with human heads and curly beards.

The great city was founded by the Persian king Darius I around 518 B.C. in present-day Iran and construction continued for nearly 200 years. For the duration of its existence, the ever-expanding metropolis was a royal estate, a bustling construction site, and an urban center that housed as many as 45,000 residents nourished by surrounding orchards and farmlands.

Glazed bricks adorned the entryway’s interior, and two identical trilingual texts, inscribed in Old Persian, Elamite, and Babylonian, read: “I, Xerxes, the great king, king of kings, king of the countries possessing many kinds of people, king of this great earth far and wide, the son of Darius the king, the Achaemenid.” Travelers would have continued through the gate onto the royal terrace, a massive 30-acre platform filled with spacious meeting halls and palaces where reliefs depicted kings receiving attendants and taming fierce creatures. The walls would have glowed from the hues of glazed tiles, murals, and inlaid gold, silver, and precious minerals. Painted with especially vibrant blues, Persepolis was an oasis that stood out from the hazy plains, says archaeologist Alexander Nagel of the Fashion Institute of Technology.

The terrace’s largest building, called the Apadana, or Audience Palace, featured 72 columns and a central court that hosted up to 10,000 people during royal festivities. Along the building’s staircases, reliefs portrayed Achaemenid guards and nobles ushering 23 delegations of different foreign peoples. Based on distinctive costumes and presents that are depicted in the procession, scholars have identified Bactrians with a two-humped camel, Ionians bearing cloth, Elamites offering daggers, and more. “Each of these parts of the empire was thought to contribute something,” says Nagel, “but the heart of the empire was Persepolis.”

The Achaemenid kings saw their realm as a cultural coalescence, and they showcased its diversity by creating a capital that integrated people, resources, and styles from their many conquered lands. To sustain such a place, they brought laborers skilled in their own traditions to the city. Building Persepolis required stonemasons, painters, lumberjacks, and gardeners. Organizing and boarding the workers necessitated managers, scribes, farmers, and cooks.

The air would have carried the odor of wet paint and brewing beer, as well as the aroma of tree resins, lit like scented candles for their fragrance. Over the din of lumber being chopped and limestone chiseled, people conversed in many languages. On the terrace, members of the royal family conferred in Old Persian, an Indo-European language that evolved into the Persian, or Farsi, spoken by more than 100 million people today. Diplomats used Aramaic, a Semitic language, the empire’s administrative and legal lingua franca. Scribes wrote on clay tablets in Old Persian, Aramaic, Elamite, and other languages. Meanwhile, below the terrace, skilled bricklayers spoke the Babylonian dialect of Akkadian, woodworkers gabbed in Egyptian, and others chatted in their own tongues.

Researchers are just beginning to understand the lives of these workers who toiled for the palace and lived in its shadow. “If you visit Persepolis, of course you see a very large platform with palaces, but this was just the royal part,” says Zohreh Zehbari, an archaeologist at the Philipps University of Marburg. “At the foot of the platform, there was a city.” Recent translations of administrative texts uncovered nearly a century ago in Persepolis have revealed where many laborers came from and the rations they were allotted. This written evidence is being complemented by finds from excavations in the urban areas below the royal terrace, as well as by paleoenvironmental research that shows how the Achaemenids transformed the surrounding environment into a vision of their empire in miniature. “The new evidence is allowing scholars to understand how, for good and for bad, the empire really transformed peoples’ lives and the landscape,” says Wouter Henkelman, a professor of Elamite and Achaemenid studies at the École Pratique des Hautes Études. “We’re now building a dossier that is incredible in richness and detail.”

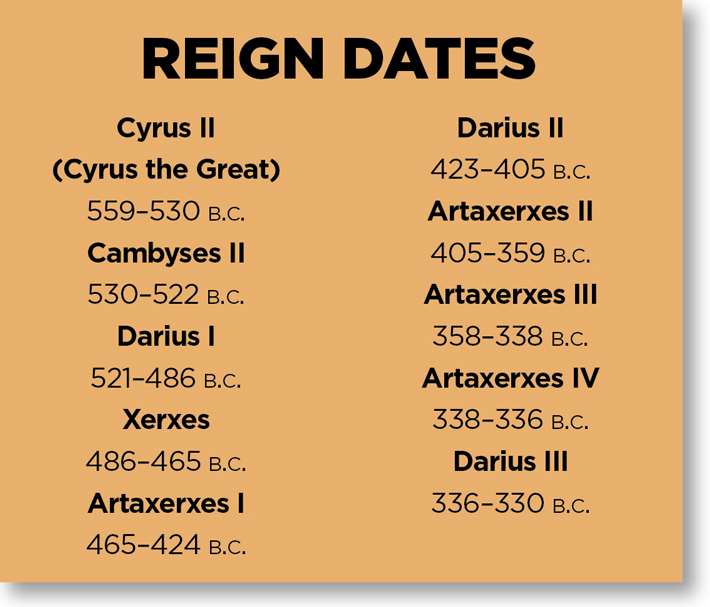

Before the Achaemenids, other imperialistic powers such as the Neo-Assyrians and the Elamites had conquered vast swaths of southwest Asia. There were also the empires of the Babylonians, farmers and city-dwellers of southern Mesopotamia, and the Medes, who were centered in the Zagros Mountain region. But the Achaemenids, an ethnically Persian dynasty, created the largest empire the world had yet known, starting from a stronghold in southwest Iran in the mid-sixth century B.C.

The first great Achaemenid king, Cyrus II, was the son of a Persian king and a Median princess. In 550 B.C., nine years after ascending to the Persian throne, Cyrus II conquered Media, unifying the lands of his maternal and paternal lines. He took Lydia in the 540s and Babylonia in 539 B.C., pursuing a campaign of conquering and absorbing other kingdoms that continued under his successors. At its greatest extent, under Darius I, the empire spanned west to the Aegean Sea, east to the Indus River, south into Egypt, and north to the Caucasus Mountains and Central Asia. “The Achaemenid Empire had a huge wealth of different ethnicities, religious systems, and cultural systems within this single overriding political entity on a scale not previously achieved or aspired to by any imperial formation,” says University of Reading archaeologist Roger Matthews.

To control this multiethnic expanse, the Achaemenid kings established more than two dozen provinces, or satrapies, run by local governors called satraps, who ensured that residents paid their taxes, fulfilled military and labor obligations, and followed royal decrees. Nevertheless, the provinces enjoyed considerable freedom to maintain their cultural and religious practices. Matthews says that the Achaemenids established “a policy of essentially letting people be, while still ruling them, organizing their lives, and demanding certain things from them.”

Satraps also commandeered labor and resources to construct cities that incorporated styles from across the empire. For example, the typical building plan for royal halls, which featured large open spaces with rows of tall columns, was likely adopted from buildings in the northern highland satrapies of Media and Armenia. Using this blueprint, the Achaemenids built at least 17 grand halls in various cities. For brickwork, the Achaemenids borrowed from the Babylonians. Colors that adorned pillars and walls were inspired by pigments invented in Egypt. And the lamassu were adapted from Assyrian and Babylonian iconography. “They put it all together and made it Persian art,” Zehbari says, creating an amalgam that represented the empire’s diverse population. Though few could travel to all the far-flung Achaemenid lands, visitors to the Persian capital could still experience the empire’s reach.

Indeed, the Persian kings proudly proclaimed this to be the case. A collection of texts known as the Susa Foundation Charters found at Susa, a city in southwest Iran that was also built by Darius I, describes the origins of the building and decorative materials the Achaemenids used. The texts mention timber from Lebanon, gold from Lydia and Bactria, precious stones from Sogdia, silver and ebony from Egypt, ivory from Nubia and India, and stone columns from Elam. The workers, too, hailed from faraway lands. There were Babylonian bricklayers, Median and Egyptian goldsmiths, stonemasons from Ionia and Sardis, and woodworkers from Sardis and Egypt.

The Achaemenids’ tendency to borrow was remarked upon, most notably by the Greeks, who described the practice with disdain. The fifth-century B.C. Greek historian Herodotus writes, “There is no nation which so readily adopts foreign customs as the Persians. Thus, they have taken the dress of the Medes, considering it superior to their own; and in war they wear the Egyptian breastplate. As soon as they hear of any luxury, they instantly make it their own.”

But modern scholars see political savvy underlying the Achaemenids’ strategy. “If you embrace another culture’s traditions, then you have a better chance of ruling them,” says Nagel. “That’s why you find so many influences from other cultures in Persepolis. The Persian kings really wanted to see themselves as peacemakers.” Toward this goal, they originated at least one artistic novelty for the region: creating carved reliefs with peaceful scenes. Instead of violent battles featuring kings vanquishing enemies, as was common in Assyrian carvings, the walls of Achaemenid cities including Persepolis are covered with tableaux in which people stand together, relaxed and chatting, holding hands or touching a companion’s shoulder.

The first large-scale scientific excavations in Persepolis took place in the 1930s, led by Ernst Herzfeld and later by Erich Schmidt, both archaeologists with the University of Chicago’s Oriental Institute (now the Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures). In 1933, a team led by Herzfeld uncovered a trove of clay tablets and fragments in two rooms that were part of the city’s fortification walls. Called the Persepolis Fortification Archive, this collection held some 15,000 tablets, mainly written in Elamite using cuneiform or Aramaic using an alphabetic script. Other languages, including Old Persian, Greek, and Akkadian, were used as well. The sheer number of texts in so many languages is unique in the ancient world. “The Achaemenids weren’t the only ancient dynasty that used bilingual, even trilingual inscriptions,” says Soheil Delshad, an epigrapher at the Free University of Berlin, “but they were the only dynasty that mass-produced royal inscriptions in different languages.”

The texts are primarily administrative and were mostly inscribed between 509 and 493 B.C., during Darius I’s reign. Their main purpose was to record the allocation of laborers, food, and drink, including rations for workers, fodder for livestock, and offerings for the gods. However, details such as laborers’ ethnicities, specializations, and work conditions were also occasionally included. “That’s the hidden part of the tablets,” says Delshad. Providing even more primary sources, between 1936 and 1938, Schmidt’s team discovered what came to be called the Persepolis Treasury Archive. Smaller in number and scope, these 746 tablets and fragments concern payments of silver to skilled craftspeople to replace or supplement their food rations between the spring of 492 B.C. and January of 457 B.C.

The tablets also enumerate the scale of labor expended on the capital. “We can now talk with real figures,” says Henkelman. “I can tell you that there were 10,000 stoneworkers on the site and calculate what that means in terms of daily rations and how they were organized in groups.” According to texts Henkelman has analyzed, many thousands of specialized workers from at least 30 different ethnic groups converged on Persepolis. The tablets reveal that their daily food rations included barley ground into bread or porridge, date or grape wine, and beer from cereals, perhaps emmer or barley. Cooks also used wine vinegar and salt to preserve food. Based on their job titles and wage scales, the majority of workers were likely fulfilling the labor obligations of their satrapies and most were not enslaved. “That doesn’t mean that I think that their lives were rosy,” Henkelman says, “or that they liked what they were doing, or that they had opted for it themselves.”

The workers’ absence must have been felt in their homelands. At least 10,000 young Babylonians, the tablets record, were forced to relocate to Persepolis, a journey that may have taken months. Considering the dates listed in the texts, it seems many workers only came to the capital during certain parts of the year. These costly, large-scale, seasonal migrations indicate how crucial the Achaemenid rulers felt it was to build a capital reflective of styles from across their empire. The kings, too, moved throughout the year among their palaces in various cities—summering in the slightly cooler Persepolis and spending winters in balmier locales such as Susa and Babylon. Matthews speculates that the royals may have timed these movements to avoid periods of major construction at Persepolis. When thousands of workers arrived and scaffolding masked buildings, the king and his court likely skipped town for the season.

Persepolis extended far beyond its monumental terrace. Beginning in 2008, the Iranian-Italian Joint Archaeological Mission in Fars, led by scholars from Shiraz University and the University of Bologna, began investigating the broader urban settlement that supported royal activities. In an area known as Persepolis West, about a quarter of a mile from the terrace, the researchers uncovered what appear to be workshops where bricks, ceramics, and other luxury building materials were produced. Archaeologists have excavated the remains of kilns, glazed bricks, metal scraps, and locally sourced pigments that they have shown were used to paint the terrace facades. These include paints that some scholars once believed had been imported, such as Egyptian blue, a coveted pigment invented in Egypt around 3000 B.C. Rather than importing this product, however, the Achaemenids made it on-site, possibly with Egyptian experts leading the operation. Chemical analysis of Persepolis West kilns and waste pits established that artisans used animal bone ash to make a glistening white finish that adorned surfaces on the royal terrace. Researchers think this technique might have been less expensive and time-consuming than the standard ancient method of extracting lime from limestone.

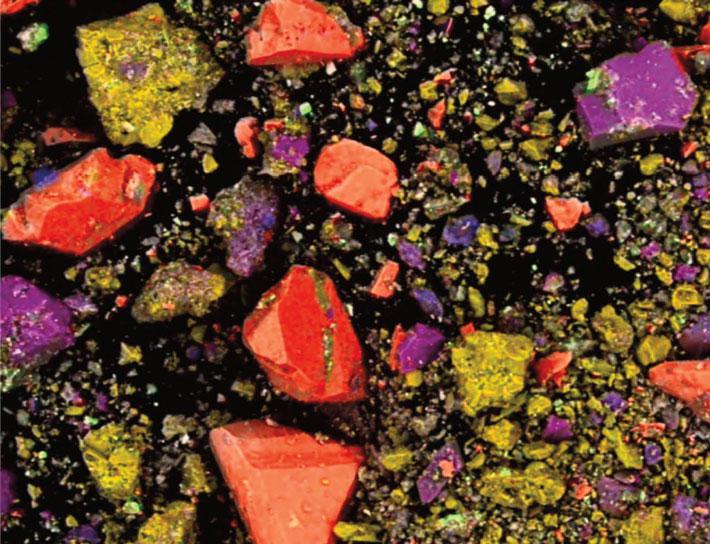

Farther out from Persepolis West, about two miles from the terrace, the team investigated a site called Tol-e Ajori. There, between 2011 and 2014, they uncovered the collapsed remnants of a brick building. After examining column bases and building foundations at the site, the archaeologists believe grand monuments once stood beyond the building. Amid the rubble, the team recovered thousands of glazed baked bricks, some decorated with reliefs that were once brightly colored. Researchers examined some 300 brick fragments with microscopes and instruments that detect materials’ chemical composition to learn about the glazes and their original hues. The bricks were baked in standardized sizes and shapes. Based on their identification of fitters’ marks in white paint that instructed bricklayers where to place each block, archaeologists have determined where individual pieces fitted in the walls.

Drawing on their understanding of the bricks’ placements and original colors, archaeologists concluded that the bricks were part of a 130-foot-long gate with interior hallways and benches. It was adorned with bulls and mythical dragon-snakes called mušḫuššu. These creatures were associated with the Mesopotamian gods Adad and Marduk, respectively, and were depicted on structures in Babylon. Two of the Tol-e Ajori bricks also bear painted Babylonian cuneiform signs, which researchers think may represent the word sharru for “king,” and include the sign ká for “gate.” It appears the Tol-e Ajori gate was a slightly larger, brick-by-brick copy of Babylon’s Ishtar Gate, providing another example of how the Achaemenid kings drew on styles from territories they had conquered. Says Matthews, “Tol-e Ajori, with the almost replica of the Ishtar Gate, shows remarkable connections between Achaemenid architecture and Babylonian practices.”

The Achaemenids’ cultural blending extended to the natural world. New paleoenvironmental research on plant remains deposited in lakes near the capital has helped reveal how the founding and growth of Persepolis changed the landscape. In 2009 and 2012, researchers collected nearly 12 feet of layered sediments from the bottom of Maharloo Lake, about 40 miles south of Persepolis. The sediments preserve plant remnants that have blown into the lake over the past 3,800 years, including periods before, during, and after the time of the Achaemenid Empire.

Paleoecologist Sara Saeidi Ghavi Andam, then of the University of Regensburg, identified pollen grains from 121 types of plants in the sediments. By analyzing which plants appeared during which periods, she detected dramatic changes coinciding with the imperial era. Before Persepolis was founded, the pollen record shows that cereal farms and pastures dotted a landscape mostly covered by natural grasslands and forests of oak and almond trees. Then, between 3,300 and 1,600 years ago—a period that includes the Achaemenid Empire—the region was filled with farms, vineyards, and orchards, growing crops such as walnuts, olives, and grapes. Some of the plants from this time were imported from faraway lands. According to Saeidi Ghavi Andam, pomegranates, which are native to Iran’s north, were very likely brought to southern Iran as saplings.

Even more distant origins can be ascribed to the olive tree, another non-native species that appeared in abundance around the beginning of the Achaemenid period. Researchers believe that the Persians encountered the tree during their conquests in the Levant or even farther afield in the Eastern Mediterranean. The victorious imperialists may have brought seedlings or saplings home along with Levantine prisoners and conscripted laborers. Support for this scenario can be found in what’s thought to be the Achaemenid Elamite word for olive, zadaum, which appears in the Persepolis Fortification Archive. Zadaum is known to have been borrowed from Western Semitic languages spoken in the Levant at the time. In addition, the robust pollen evidence for olive groves in Achaemenid territory contradicts ancient Greek and Roman accounts claiming that Persia and its neighboring regions grew every kind of fruit—except olives.

Scholars have now identified the names of more than 40 tree types mentioned in some 400 texts in the Persepolis archives. While most of these texts mention harvested fruits, nuts, or aromatic resins, two tablets discuss how the trees themselves were cared for. The texts account for well over 10,000 trees in all and some list the locations of and individuals responsible for particular stands of quince, mulberry, apple, pear, and olive trees, as well as numerous species that have yet to be translated. For example, the texts state that more than 3,500 karukur trees—an undeciphered name—were grown at 11 locations. Other texts say 7,500 portions of this tree’s fruit were laid upon the royal table, but just 240 servings were distributed to hundreds of workers. Some of the people named in the texts—Maraza, Napapartanna, Zimakka—held a title that may mean deputy fruit manager. They oversaw deliveries and supervised workers based in different administrative districts near Persepolis. It’s clear that the Achaemenids deliberately collected trees from across the empire to grow at home. “The kings decided this valley was going to be dedicated to fruit production,” says Henkelman. “It’s regional planning.”

Fostering multiculturalism in Persepolis might have been a strategy the Achaemenids employed to promote peace—but it also strained their economy. According to Cornell University archaeologist Lori Khatchadourian, maintaining the capital’s blend of architectural styles constrained and consumed the Achaemenid rulers. While Darius I’s original plan for the terrace likely entailed a handful of buildings along with gardens and open courts, later kings commissioned increasingly grand structures. “It’s clear that subsequent Persian kings in the Achaemenid Dynasty decided to add their own marks to the terrace site through massive building programs,” says Matthews. In the end, at least 473 columns of stone and wood supported terrace buildings, at least two of which had 100 columns each. Not only did the kings need the raw materials and skilled workers to build these structures, they also had to repair and renovate them after decades of use.

This depleted their resources and may have distracted the kings from more urgent matters, including revolts in Egypt and Babylonia, as well as the growing threat from Greece. Perhaps this helps explain why the empire was vulnerable to invasion and defeat by Alexander the Great in 330 B.C. Adding insult to injury, after spending four months on the royal terrace, the conqueror burned Persepolis down. According to the ancient Greek historian Plutarch, after torching the city, Alexander’s soldiers spirited away its treasures on 20,000 mules and 5,000 camels. Two centuries after its founding, the great multicultural city was reduced to ruin. Despite Persepolis’ abrupt end, the Achaemenids’ vision for their city left an enduring legacy. The kings constructed a capital that incorporated peoples, styles, and materials from varied and distant lands. In doing so, they communicated a then-radical view that empires of diverse cultures function best when people are allowed to maintain their traditions and ways of life. This seems to have been correct, as the Achaemenids’ massive empire survived for two centuries through the reigns of 10 kings. Perhaps it is best, as Matthews says, to be the conquerors who let people be.