During the 19th Dynasty (ca. 1295–1186 b.c.), the village of Deir el-Medina, on the Nile’s west bank in Upper, or southern, Egypt, was home to a community of civil servants and artisans who built and decorated the royal tombs in the nearby Valley of the Kings. Scholars are on unusually familiar terms with these people. “As expert scribes and draftsmen, they left quite a lot of writing,” says Egyptologist Rob Demarée of Leiden University. At the site, archaeologists have excavated tens of thousands of texts written on papyrus and ostracons—discarded pieces of pottery or stone used like scrap paper. In 1997, Demarée began compiling these texts into an online database that now contains more than 5,000 records. Although some texts are accounts of mundane work, others paint a portrait of life in the ancient village.

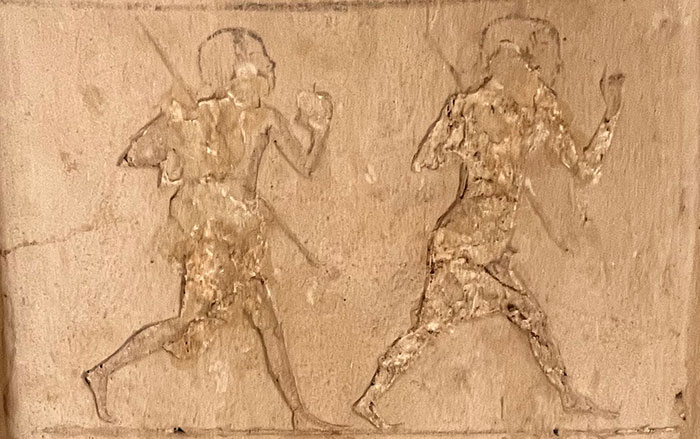

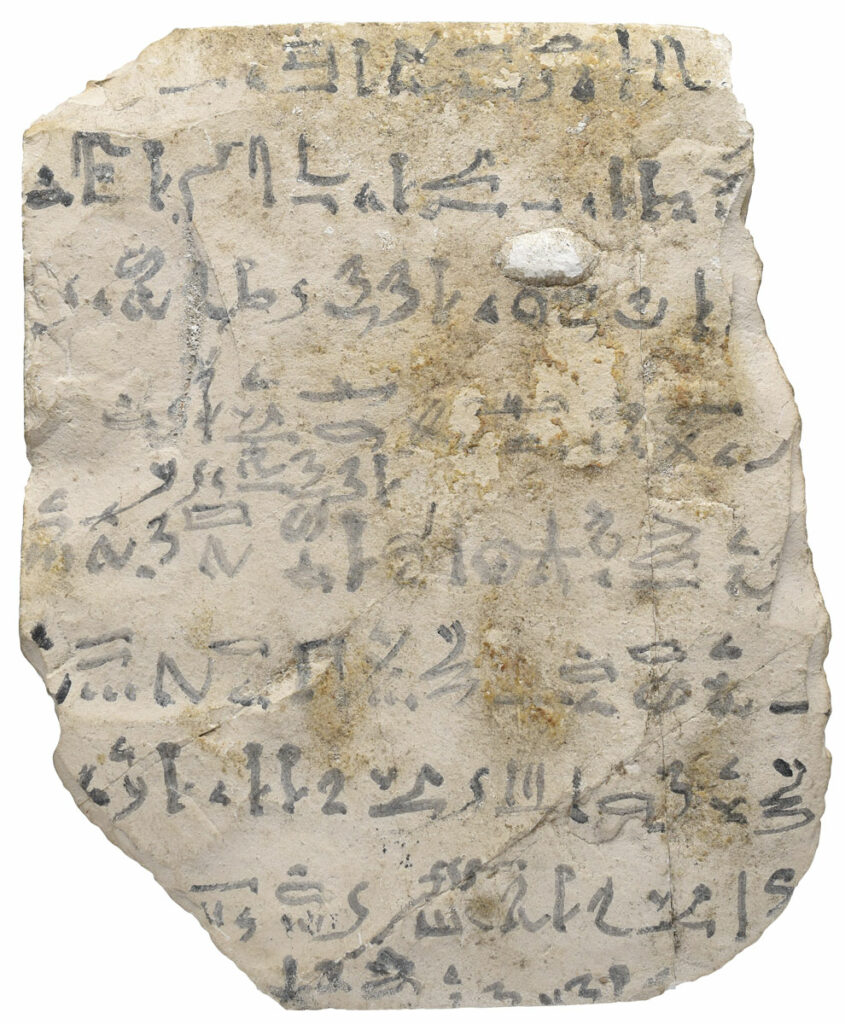

About 25 years ago, while perusing Berlin’s Egyptian Museum and Papyrus Collection’s newly digitized archive of ostracons, Demarée came across a curious note on a limestone ostracon that had been found at Deir el-Medina in 1913. The note reads: “To Khay. Let there be brought some fresh goose fat directly, very, very quickly because the cat has eaten that which was brought to me yesterday.” The exploits of the mischievous feline caught Demarée’s attention, but the brief memo provided no further context for the rush request.

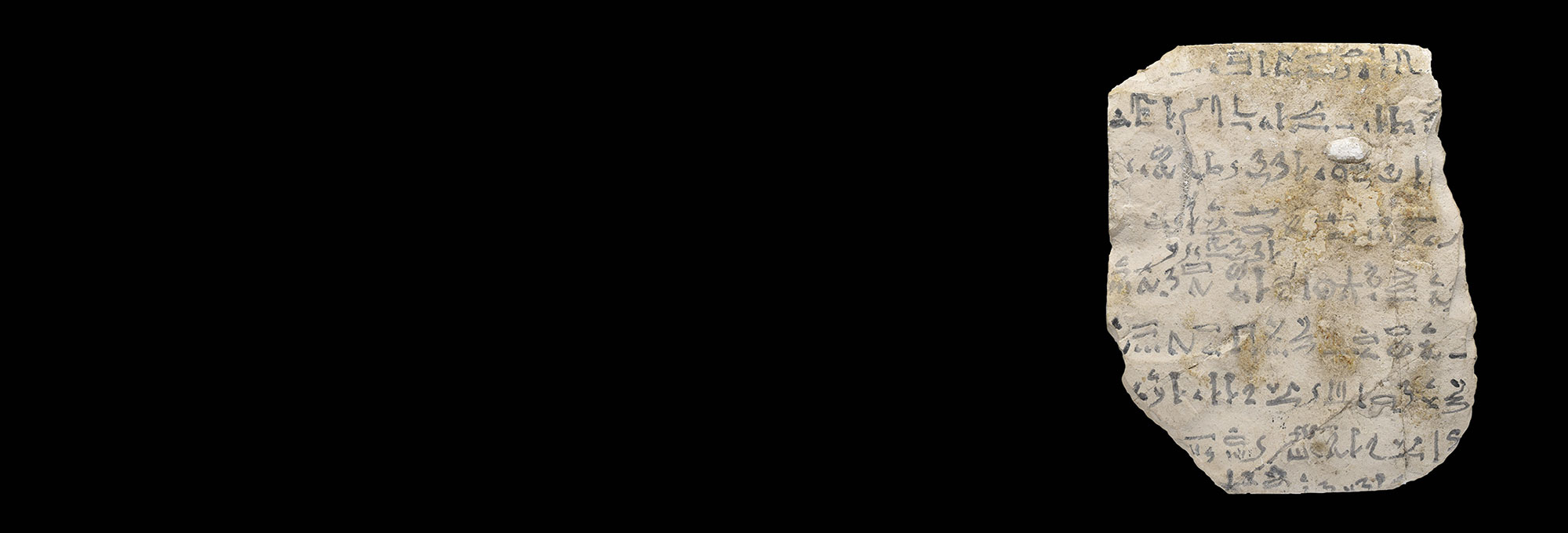

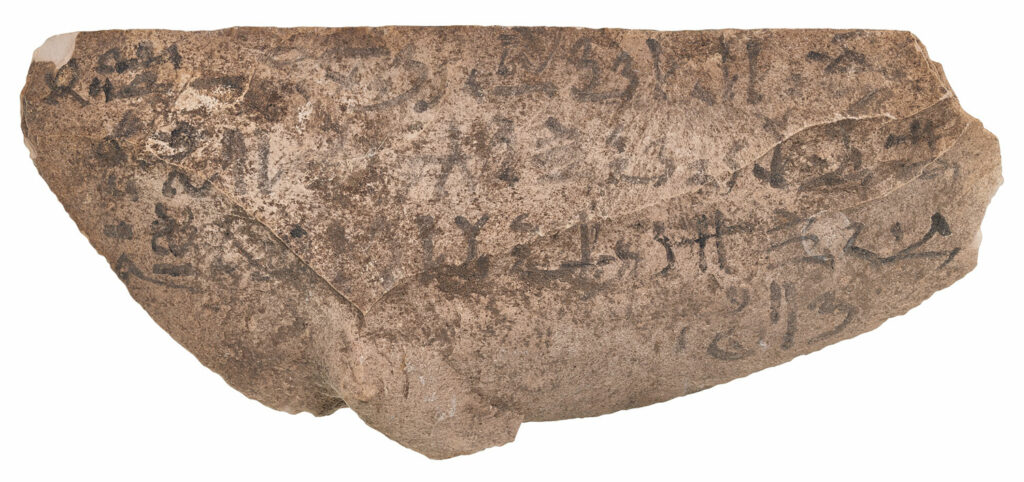

Years later, a colleague sent Demarée the text of a related letter written on another limestone ostracon, this one housed in the Royal Pump Room Museum in the northern English town of Harrogate. It reads, in part: “Draftsman Nebre cannot sleep well. Let someone look for some fresh goose fat and let it be brought at once. Please go to the woman who knows about deaths.” Both notes were written in the same hand using hieratic, a shorthand script invented by Egyptian scribes to simplify the complex system of hieroglyphs.

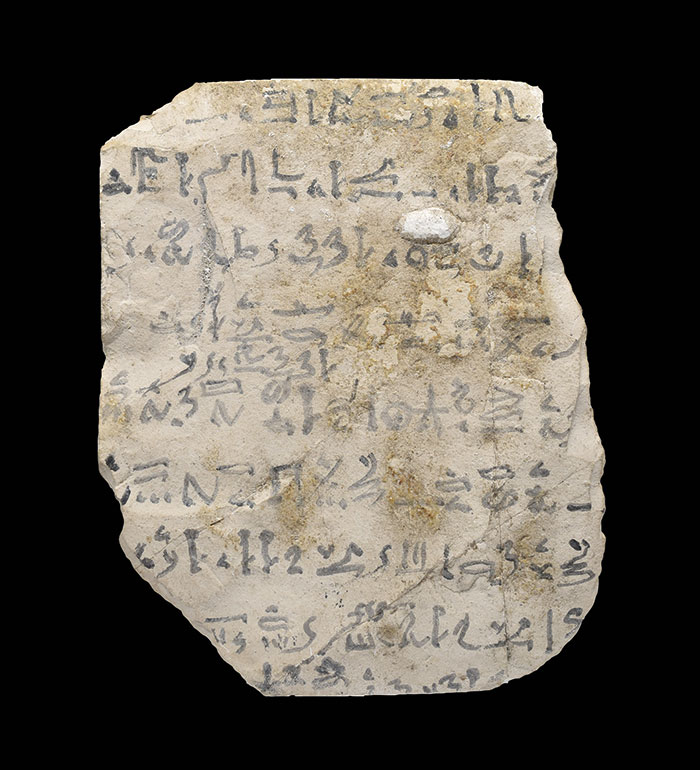

The Harrogate ostracon identifies the sender as Nakhtamun, who is known from other texts to have been Nebre’s son and Khay’s younger brother. All three men worked as draftsmen in the tombs of the thirteenth-century b.c. pharaohs Seti I and Ramesses II. Nebre had myriad health problems, to which he alludes on several steles found at Deir el-Medina, beseeching different gods to restore his health. The village’s other residents, Demarée explains, took similar actions in the face of misfortune. “People sinned against the gods by not observing their rules,” he says. “Then they became very afraid and tried to propitiate the gods by putting up a stele or promising an offering.” To cure his repeated bouts of illness, Nebre and his sons dedicated steles not only to the principal god, Amun, but also to deities such as the sky god Haroeris, the cobra goddess Meretseger, and goddesses known as “the good swallow” and “the good cat.”

Nakhtamun’s urgent demand for a goose-fat sleeping aid implies that, in addition to his bodily ailments, Nebre was suffering from nightmares. “The ‘woman who knows about deaths’ was a midwife in the village who probably had other abilities,” Demarée says. “From the other texts in which she is mentioned, you get the idea that people consulted her in times of need.” Even if she had been able to supply more goose fat to replace the batch purloined by the cat, the remedy would have been unlikely to offer Nebre much relief. “Rubbing him with goose fat probably would have relaxed the muscles somewhat,” says Demarée, “but that wouldn’t have cured a nightmare.”