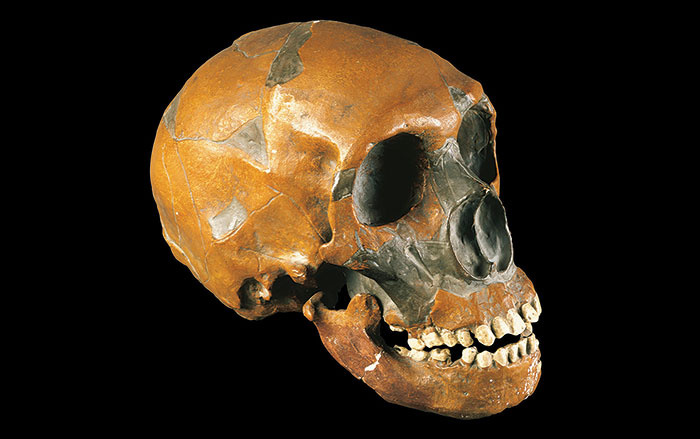

STANFORD, CALIFORNIA—According to a report in The Atlantic, research conducted by evolutionary biologists Dmitri Petrov of Stanford University, David Enard of the University of Arizona, and their colleagues suggests an influx of Neanderthal genes may have boosted the immunity of modern human populations who moved into Europe from Africa tens of thousands of years ago. Genes can offer protection from disease by altering the way human proteins interact with viruses. Scientists think both groups of early humans would have been vulnerable to unfamiliar viruses when they first came in contact with each other, but interbreeding could have exchanged genes that offered some resistance to infections. “We call it the poison-antidote model,” Enard said. So Enard and his team compared genes in segments of modern human DNA known to have been inherited from Neanderthals with a list of more than 4,500 human proteins known to interact with viruses. They found that genes inherited from Neanderthals by modern Europeans react with RNA viruses such as HIV, influenza A, and hepatitis C, which indicates the genes may have helped modern human ancestors combat ancient RNA viruses. Enard also examined the sequenced genome of a Neanderthal man who lived in Siberia some 50,000 years ago, and found that he carried stretches of modern human DNA that also corresponded with human-virus-interacting proteins. These genes may have offered him some protection from viruses introduced by modern humans. For more, go to “Decoding Neanderthal Genetics.”