"God wills it,” cried the crowd gathered on November 18, 1095, in the northern French city of Clermont in direct response to Pope Urban II’s entreaty that they come to the aid of their Christian brethren in the east. The Byzantine emperor Alexius I Comnenus, threatened by the growing power of the Seljuk Turks—who had already captured the important Christian cities of Antioch and Nicaea—had requested the pope’s help to defend his territory and keep the Turks from his capital at Constantinople. What began with a request for military assistance turned into a campaign to defend Christendom and reinstate Christian control over Jerusalem, which had been ruled by Muslims for more than three centuries.

Tens of thousands of people—from armored knights on horseback wearing tunics emblazoned with red crosses to ragtag bands of poor peasants, some of whom branded their flesh with the sign of the cross—set off the following year on the arduous trek of nearly 2,000 miles to the Holy Land. Only a century later did they become known as Crusaders, from the French term for “way of the cross,” and this first wave of Europeans was dubbed the First Crusade. After winning back Antioch and Nicaea, the Crusaders eventually seized Jerusalem on July 15, 1099, massacring all of its Jewish and Muslim residents—30,000 by one account—and leaving the city, holy to all three faiths, awash in blood.

The famously intolerant invaders established control over an area roughly the size of today’s Israel and West Bank, which they called the Kingdom of Jerusalem. In their wake, an array of Europeans—nobles, mercenaries, criminals, and pilgrims, among others—primarily from France and Germany, flooded into the Near East. For the next nearly 200 years, their power waxed and waned.

In the first century that they were there, they crowded into the region’s cities and established farms and vineyards in the countryside. Then, in 1187, they surrendered Jerusalem to the Muslim military leader Saladin. For the second century of their occupation, they were largely confined to a thin coastal strip along the Mediterranean Sea. By the time the often-fractured Muslim forces united to drive out the last Crusader in 1291, the Europeans had launched six major assaults on the Levant. This violent collision of European Christians and Middle Eastern Muslims took a terrible human toll and created a deep-seated antipathy that reverberates to this day. It also exposed a provincial western Europe emerging from the Dark Ages to a wider world filled with ancient cities, erudite scholars, and a vibrant new religion. In turn, the Crusaders left an indelible mark in the form of nearly 100 castles found across the modern states of Cyprus, Egypt, Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, Syria, and Turkey.

These medieval fortifications, coupled with the few written accounts left by Christian and Muslim sources, have long painted the Crusaders as little more than aggressive invaders focused on murder and plunder and uninterested in creativity or innovation, says Adrian Boas, an archaeologist at the University of Haifa. But he and a new generation of excavators are now uncovering a more nuanced picture of Crusader life from digs in castles, rural settlements, and urban areas, learning what they built, ate, and drank, how they fought, and even how they were buried during their long sojourn in the East.

EXPAND

The Frankish Settlements

Among the warriors and pilgrims who arrived in the Middle East during the Crusades were European immigrants eager to begin a new life in a new land. Historians have long assumed that the vast majority of these people, typically called Franks though not all were French, huddled in well-protected towns and avoided the potentially dangerous countryside. Five previously excavated but newly reexamined Crusader-era settlements, all located just north of Jerusalem, are now beginning to reveal how these Europeans made their homes in rural areas as well. These towns have long puzzled archaeologists, who in recent decades have exposed twelfth-century homes built of sturdy stone walls, some more than six feet thick, packed together along a central road facing the street. This layout is unusual in the Near East, where central courtyards are the norm, and homes are rarely built against one another except in cities. The structures often had two stories and barrel-vaulted ceilings, rather than the one-story buildings with domed or flat roofs typical of the region.

Since the 1940s when these small towns were first excavated, archaeologists theorized that they were built during the twelfth century when the Crusaders were at their peak of power and a measure of peace prevailed around Jerusalem. But archaeologist Elisabeth Yehuda of Tel Aviv University noticed that the buildings were themselves designed as miniature forts, with second stories accessible only by way of a narrow staircase or removable ladder, and therefore easy to defend from attack. She argues that the second stories were, in effect, temporary refuges in times of trouble.

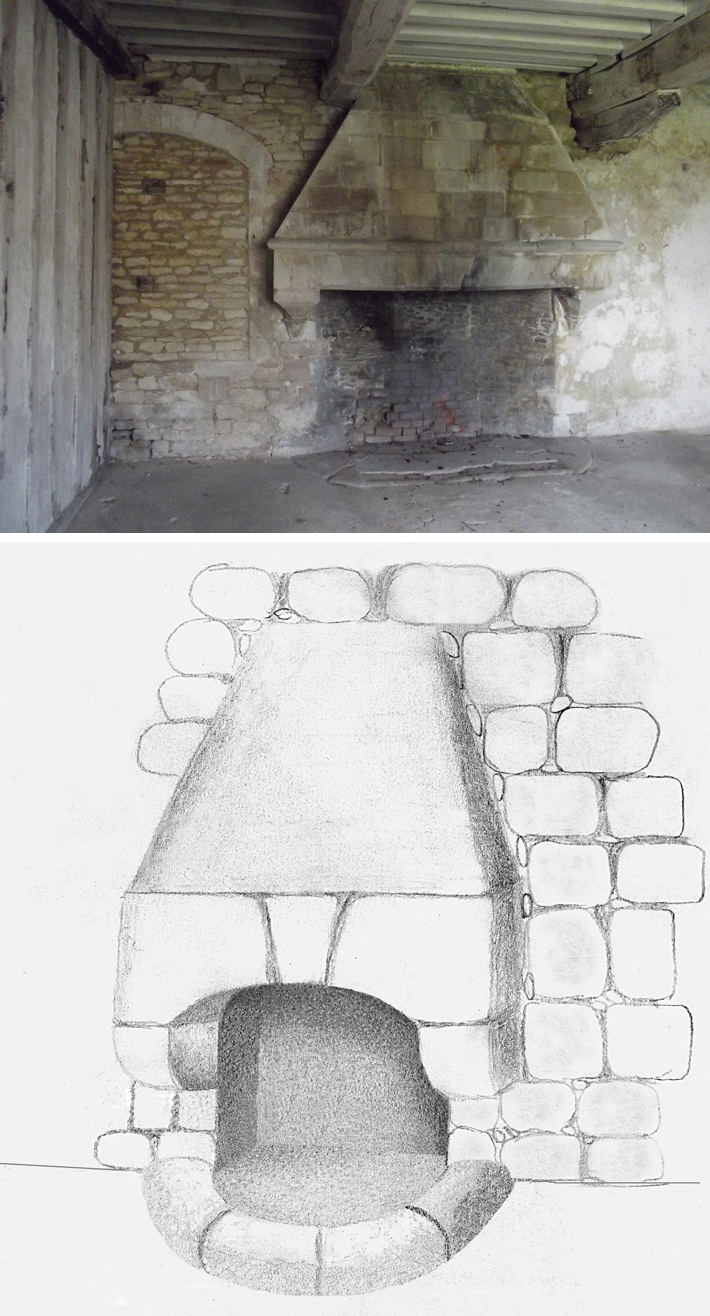

While conducting research in European archives, Yehuda found examples of stone houses of similar design in urban Europe also dating to the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. Though not quite as fort-like as the Crusader structures, they reflected the growing prosperity of artisans and merchants through their sturdy construction and careful attention to detail. She then focused on the decorative corbelled fireplaces in the main room on the first floor of many of the Frankish dwellings. These are unique in the Middle East, and she discovered they matched those of some well-to-do homes of the era in France and Germany. Used for heating and cooking, they signaled the wealth and sophistication of the owner at a time when open fireplaces were the rule. “They were showpieces,” Yehuda says. “It was the first thing you would see when you walked in the door.” Excavations also showed that residents of the settlements dined on fine tableware imported from around the Mediterranean.

The inhabitants of the Frankish settlements were neither peasants nor knights, says Yehuda, but skilled artisans and traders who intended to make this new land their permanent home. They also planned to maintain their European identity. “The settlers didn’t fuse with the local environment. They flouted their otherness in remarkable ways such as building in stone to say that they were here to stay,” she adds. They made a conscious choice to live in the countryside rather than living in the Crusader cities notorious for crowding and disease.

In the summer of 1187, Saladin’s forces assembled on the shore of the Sea of Galilee 75 miles north of Jerusalem. The king of Jerusalem, Guy Lusignan, in turn, gathered his troops at a spring at Sepphoris to prepare for the battle. Sepphoris was considered the traditional site of the birth of Jesus’ mother Mary, at which time it was a thriving Roman city, and it served as a strategic watering hole for Greek, Roman, Byzantine, Arabic, and Ottoman travelers and armies through the millennia. Crusaders had used the area on and off for more than a century.

As some 20,000 cavalry and infantrymen readied themselves, the barons argued over whether to venture out on the plain to the east to attack Saladin, or to remain in the easily defended camp. The king chose to attack, and thousands of men set out on an extremely hot July day, carrying a standard containing a splinter of what they believed to be the True Cross. Raymond III, Count of Tripoli, had argued against the attack, possibly because he had a covert agreement with Saladin to support him as the next king of Jerusalem.

Outnumbered, exhausted, and short of water, the Crusaders were quickly crushed. Accounts note that, after heavy fighting, Raymond and his men fled north to safety.

Guy Lusignan was imprisoned at Damascus, and by October, Saladin had captured Jerusalem, although he refrained from massacring the city’s Christian population. Instead he expelled the Crusaders, who retreated to their coastal castles in Tyre and Tripoli in modern Lebanon. Europeans would never again regain full control over the holy city. When Pope Urban III heard the news, he is said to have died of grief. His successor promptly called for another Crusade to recover Jerusalem.

One of their most ambitious—and peculiar—works is located about 22 miles inland from Acre, the main Crusader stronghold on the coast. The castle, which sits high on a mountain, was built by the warrior monks of the Teutonic Order in the 1220s, a time when the Crusader kingdom was under increasing pressure from Muslim armies. These German men, who were typically of high status, had organized in Acre in 1190 to protect and care for Christian pilgrims to the Holy Land. They named the castle Starkenberg or “Strong Mountain,” although today it is known by its French name of Montfort. It was designed not to protect the surrounding area, but to serve as a private headquarters, archive, and treasury for the wealthy order.

EXPAND

An Unexpected Cemetery

Athlit Castle, which was built by the Knights Templar in the early thirteenth century, now sits inside the perimeter of an Israeli Defense Force training camp on the coast between Haifa and Tel Aviv. Its cemetery, the largest known Crusader resting place in the Middle East, lies just outside the camp’s fence. Here, over a period of about eight decades, the remains of thousands of people were buried in an orderly rectangular space a football field long, and almost as wide.

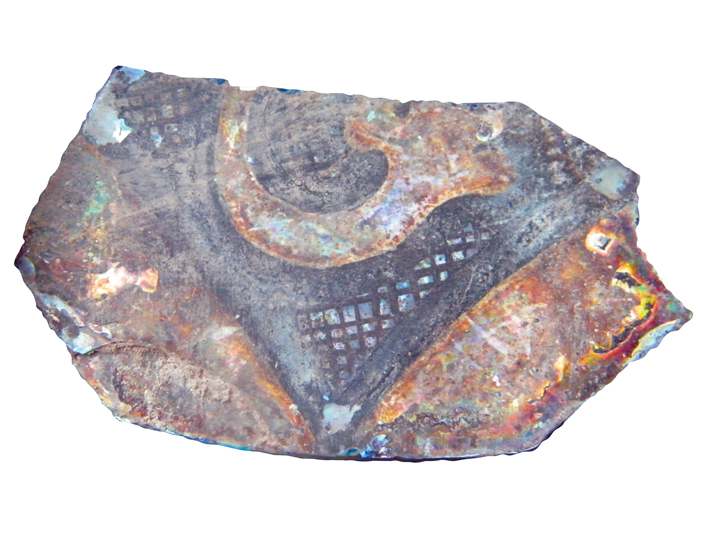

There are many unusual features of the Athlit cemetery that seem to contradict conventional thinking about European burial practices of the time. In the thirteenth century, the castle stood above a thriving town to the east and the fertile countryside beyond, but, unusually, the cemetery was located some distance away, close to the beach. Furthermore, all other known Crusader cemeteries, with the exception of one against Jerusalem’s walls, include a church or chapel—but not Athlit. In a 2006 survey, archaeologist Jennifer Thompson, then of Cardiff University, speculated that the cemetery was in use before the town and its church, which may never have been completed, and remained the sole place for burial through the life of the community.

And while Crusaders in other locations—like most medieval Christians—typically were interred with their feet facing east, in anticipation of Christ’s return from that direction, Yves Gleize of the University of Bordeaux, who has been excavating the cemetery for the past four years, notes that the Athlit burials are generally oriented with their heads to the castle and their feet to the northeast.

It is the number of burials, however, that is most exceptional. British archaeologist C.N. Johns, who excavated the site in the 1930s, counted 1,700 graves, but Gleize puts the number at a minimum of 5,000, and perhaps as many as 8,000. “That means an average of five or so dead per month, which is too many for just the castle or even town inhabitants,” he says.

There is little doubt the graves are from the brief period between 1218 and 1291, given the thirteenth-century coins and potsherds Gleize has uncovered, but where all those people came from remains unclear. They were almost certainly Europeans, as Gleize has determined that the Athlit dead were primarily buried in shrouds and lowered into pits that then were covered with a lid anchored with stones, the common method in France in that period. Some may have been pilgrims who chose to be buried at Athlit, perhaps due to the proximity to relics in the castle’s chapel, as might be the case of a man in his 50s found with his arms folded over his chest and his hands in what may have been an attitude of prayer. Metal pieces found next to his skeleton likely were part of a staff, a common accessory for pilgrims and the first example found in the region. Others may have been victims of violence, such as a man with a bashed skull and an arm injury that seems to have been inflicted by a heavy sword. Gleize speculates he could have been a Templar victim of a Muslim siege.

Haifa University’s Boas launched an effort in 2011 to excavate Montfort, which today is found in the middle of an Israeli national park just south of the Lebanese border. A previous expedition had been undertaken in 1926 when New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art sent a team to recover a suit of armor for the collection of its Department of Arms and Armor. That effort failed.

The sprawling complex of Montfort sits at the top of a rock-cut road, deeply scored to prevent carts carrying building stones that could weigh up to 10 tons from rolling downhill, according to Rabei Khamisy of the Israeli Antiquities Authority, who grew up in a nearby village and now directs the excavations. It was partially demolished less than a half century after its construction by Muslims intent on preventing a Crusader return. By digging through tons of debris and rock, the team has documented the castle’s design and decoration and cataloged a collection of small artifacts. The material they found contradicts the conventional view of Crusaders—and particularly of these warrior monks—as existing in crude conditions. Montfort, they discovered, was a formidable place of stylish living comparable to the fine manor houses and wealthier monasteries of its day in Europe.

The castle’s central keep is now just a wide stone platform with a few ruined walls made of gargantuan stones, but it once soared another 100 feet into the sky. Underneath, the archaeologists uncovered deep cellars for stocking supplies. Above the cellars they traced the remains of a finely plastered white floor and decorative pilasters of a large hall, as well as a chapel with an elegant apse that is still partially intact. The third floor once held sumptuous apartments for the order’s highest officer, the Grand Master. These boasted vaulted ceilings and frescoed walls decorated with gilded wood and punctuated with stained-glass windows, shards of which were found in the debris. “These were luxury accommodations,” says Khamisy. In a courtyard below the central keep a stone-carved wine press large enough to fit a small car still sits, evidence that local vineyards covered at least some of the terrain in the thirteenth century.

Along the southern section of the castle’s long outer wall, excavators working in a round tower in 2016 found an array of day-to-day artifacts, including iron waste from a forge and evidence of a workshop that turned bone into buttons and other objects. The discovery showed that there had been a thriving community of on-site artisans who supplied the knights with manufactured goods. The team also recovered a large number of glass fragments from delicate drinking vessels, a board for Nine Men’s Morris, a strategic game similar to checkers, along with the game pieces, and bones of European domesticated pigs, presumably brought by the knights to provide a taste of home.

On the mountain’s northern slope, the outer fortifications are topped with the only surviving Crusader wall crenellations known in the Middle East. Near the gate in the outer wall, which included a portcullis that could be lowered in case of a threat, the excavators uncovered remains of elaborate rooms complete with flagstone flooring and high ceilings supported by double-arched wood beams. The rooms were littered with rusty bits of horseshoes, horseshoe nails, bells, spades, axes, and saddling buckles and bells, along with thirteenth-century coins. Clearly, these were the castle’s stables. “Even the horses here lived well,” adds Khamisy.

Despite their seemingly impregnable mountaintop position, the end for the Teutonic knights at Montfort came quickly. The sultan Baibars, the Mamluk ruler of Egypt who had previously defeated the Mongol army at the Battle of Ain Jalut in 1260, took up Saladin’s campaign to rid the region of Crusaders. By this point, the Crusaders’ territories had contracted to just a few havens on the coast, and the castle was an isolated and vulnerable European outpost. Promised safe passage to Acre, the knights abandoned their headquarters after a two-week siege. Boas’ team has unearthed more than 40 stones weighing more than a ton each that were hurled at the castle by the sultan’s forces in 1271, as well as indications that some walls were undermined. The sultan had his men destroy much of the castle by burning so much wood that the resulting heat caused the building to collapse.

As the defeated knights marched to Acre under the watchful eyes of their Egyptian guards, a rival Christian order known as the Knights Templar still clung to control of an even larger and more ornate fortress. Built 50 miles south of Acre, on a rocky outcrop jutting into the Mediterranean, the structure, begun in 1218, was variously known as the Castle of the Son of God and Pilgrim’s Castle, and today is commonly called Athlit.

The Knights Templar, an organization far wealthier and more powerful than the Teutonic Order, was created in 1119 to guard and care for Christian pilgrims. These European knights maintained their headquarters on Jerusalem’s Temple Mount, known to Muslims as the Noble Sanctuary, until they were ousted in 1187. Nevertheless, they continued to expand their domain in the Levant throughout the Crusader era. They eventually became key financiers who garnered tremendous wealth and power in the Near East and in Europe until they were disbanded in 1307 by a jealous French king, Philip IV. Drawn to the area’s fertile fields, vineyards, and woods, and to the strategic harbor formed by a tongue of rocky land once used by Phoenicians more than 2,000 years before, the Templars built Athlit, a massive complex. To separate the mainland from the castle, they dug a wide, deep ditch that could be flooded with seawater from either side for defense, and then constructed a nearly 20-foot-thick wall that towered almost 50 feet high and was studded with watchtowers. An inner wall, twice as thick and reaching twice as high, protected the castle keep, which, according to contemporary sources, could house 4,000 soldiers.

Unlike their treatment of other Crusader forts such as Montfort, the Holy Land’s Muslim rulers left Athlit largely intact after the Europeans departed for the last time in 1291. Its impressive walls, though damaged by earthquakes and stone robbers, are still plainly visible along the train line linking Haifa with Tel Aviv. Until recently, however, the site has been as inaccessible to archaeologists as it once was to the Muslim armies who, for nearly a century, sought to capture the European stronghold. The castle’s ruins now sit inside the fences surrounding an Israeli naval commando base and are off-limits to civilians. Except for a brief British excavation in the 1930s, little research has been done on what Boas calls “the most remarkable and most notorious of Templar castles.” In 2017, Vardit Shotten-Hallel of the Israel Antiquities Authority gained access to Athlit after lengthy negotiations with the Israeli military.

The only contemporary description of Athlit comes from Oliver of Paderborn, a German chronicler and religious leader during the Fifth Crusade (1217–1221). He writes in his Historia Damiatina that Athlit’s builders had conducted their own sort of archaeological excavations. They stumbled on an ancient wall and found, “by the generosity of God,” a hoard of Hellenistic or Roman silver coins that helped pay off the cost of construction. The fortress, Oliver adds with maddening brevity, included a chapel, a palace, and “several houses.” He also shares that the Templar Grand Master resided for a time at the castle, and that the French queen Margaret of Provence—the only woman to lead a Crusade, after her husband, the king, was captured in Egypt—gave birth there around 1250. The queen’s apartments have yet to be identified. Later accounts mention that Athlit was the site of the Templar’s prison in the Holy Land, where, according to a contemporary report, two men accused of sodomy were sequestered in irons. Shotten-Hallel’s initial survey of the castle’s eastern tower revealed a long, narrow room with walls pierced by holes. Bar-Ilan University historian Yvonne Friedman suspects this may have been the prison, and that the holes accommodated iron shackles.

Devout pilgrims may have formed the largest group of visitors to Athlit. With Jerusalem inaccessible to Christians during much of the thirteenth century, the castle may have served as an alternate pilgrimage destination. Nobles, soldiers, and mercenaries accounted for only some of the Europeans who traveled to the Middle East in this era. In addition, thousands of pious pilgrims, from well-heeled merchants to penniless peasants, made the difficult journey in creaky ships threatened by storms and pirates in order to reach the Holy Land. The Catholic Church encouraged this flow by granting indulgences—remission of sin in the afterlife—to those who visited sacred sites there. According to the recollections of one pilgrim, the relics of the martyr Saint Euphemia were housed in the castle chapel at Athlit following their “miraculous translation” from Constantinople. After studying the chapel, which remains partially intact, Shotten-Hallel theorizes that it might have served as a kind of substitute Church of the Holy Sepulchre. The design, with a rotunda and twelve columns, resembles the Jerusalem shrine marking the place where Jesus is said to have been crucified and where his empty tomb is located. “It is as if they were creating a synthetic image of the holy city,” she says.

Athlit survived two major sieges and outlasted even Acre in the waning years of the thirteenth century as Muslim forces closed in on the increasingly isolated Crusaders. After the 1291 surrender of Acre, Athlit’s Templar defenders finally evacuated their fortress. They were among the last Europeans to leave the Holy Land. Most returned home, though a few Crusaders clung to the city of Tartus on the Syrian coast for another decade. The Kingdom of Jerusalem lingered on the island of Cyprus for another century or two, but efforts to use it as a launching pad for new Crusades failed. Those castles not destroyed by Muslim forces were repurposed to fend off future invasions. It would be another five centuries before a European army, this time led by French leader Napoleon, would again land on eastern Mediterranean shores.