Early this year, on the outskirts of Beiwuzhuang village in northern China’s Hebei Province, someone started dredging a riverbed. It’s not an unusual occurrence in China, a land of fast development and silted channels. But when local archaeologists heard about this particular effort, they came running. “In 2004, our team had discovered a few fragments of Buddhist statues in the riverbed,” says He Liqun, a member of the archaeological team working there. “So ever since, this had been an area of concern.”

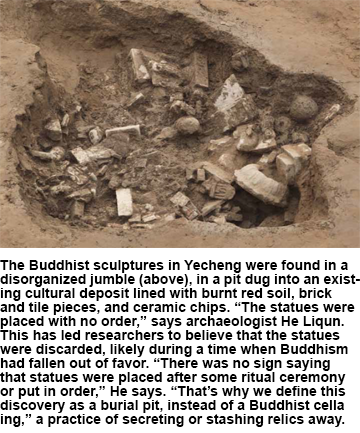

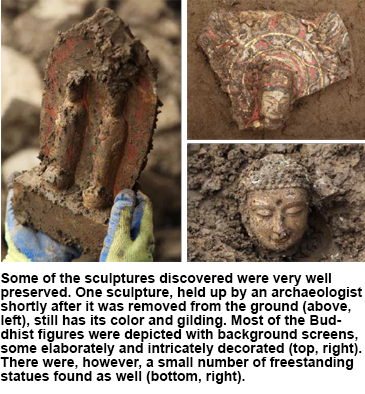

China’s archaeological regulations tend to favor protection over excavation, so the archaeologists had let the riverbank be in 2004. But the dredging made excavation a priority, so this time the team arrived ready to begin exploratory drilling. In January 2012, they hit what He calls a “burial pit”—a roughly dug hole in the ground, five feet deep and 11 feet wide. The burial pit contained no coffins or bones, but rather the largest cache of Buddhist sculptures ever discovered in China. Almost 3,000 (2,895, to be exact) were excavated at the site—some of white marble, others of limestone or ceramic—covering more than 500 years, from the Northern Wei Dynasty (a.d. 386–534/35) into the Tang Dynasty (a.d. 618–907). The sculptures offer archaeologists a glimpse into the place of religion in ancient China and into the politics and history of one of its most influential cities.

The burial site is located on the outskirts of the ancient city of Yecheng, a metropolis that for centuries controlled an important stretch of land north of the Yellow River, and which has been excavated by archaeologists since 1983. During the Three Kingdoms Period (a.d. 220–280), the famous warrior Cao Cao (“China’s Most Notorious Villain,” September/ October 2010) made Yecheng his base. Around 40 years later, during the Western Jin Dynasty, a rebel army occupied the city and set fire to its temples. Its history is one filled with turmoil. “As an ancient capital, Yecheng was an all-encompassing city of palaces, government offices, city walls, city gates, residential quarters, workshops, cemeteries, and gardens,” says He. It had a religious role and, He says, “during the late Northern Dynasties [Northern Wei through Northern Zhou, a.d. 386–581], when it had become a cultural center of Buddhism, Yecheng had an abundance of Buddhist relics.”

Records are unclear on when Buddhism first reached China from India, but the religion was slowly gaining a foothold by the Western Han Dynasty (206 b.c.–a.d. 24). Buddhism offered a spiritual alternative to China’s domestic religions—it focused on individual salvation rather than the service to society prominent in Confucianism, and it had more institutional structure than Taoism. After the decline of the Han Dynasty, as warriors including Cao Cao, Dong Zhuo, and Liu Bei battled for dominance, Buddhism increased in popularity. By the time Yecheng became capital of the Eastern Wei Dynasty (A.D. 534–550), Buddhist temples throughout China were becoming rich from imperial and official grants of land and money. Even as the temples grew wealthy, Buddhism nonetheless held a precarious position. It continued to be considered a foreign religion, it was always subordinate to the secular state, and critics went so far as to accuse the religion of corrupting Chinese society. Chen Fan, a Confucian scholar who lived during the Eastern Han Dynasty (a.d. 25–220), wrote that it caused people to “go bankrupt flattering the Buddha.”

According to Han Sheng, a historian at Shanghai’s Fudan University, there were two reasons that, despite all the opposition, Yecheng was particularly open to Buddhism. First, it was a diverse city, often in the hands of leaders who came from outside the boundaries of China’s dynasties, which made it more accepting of a religion with a foreign origin. Second was the city’s place in China’s ongoing succession of dynastic wars—the tenets of Buddhism provided comfort to a war-weary populace.

“Yecheng was a very important military city,” says Han, “a stronghold during a period of endless war.” It was the capital of a series of brief empires that followed the fall of the Han Dynasty. It was powerful until a.d. 580, when a Yecheng general named Yuchi Jiong opposed the Northern Zhou Dynasty emperor, Yang Jian. “[Yang Jian] had to use all of his power to crush [Yuchi Jiong],” says Han, “and the biggest battle was in Yecheng.” Yang razed the city and forced most of its occupants to move to nearby Anyang. “In [traditional, native] Chinese religions, there was no concept of having a soul,” Han explains.“When so many people were dying, they liked the idea of having ta soul that they could take care of.”

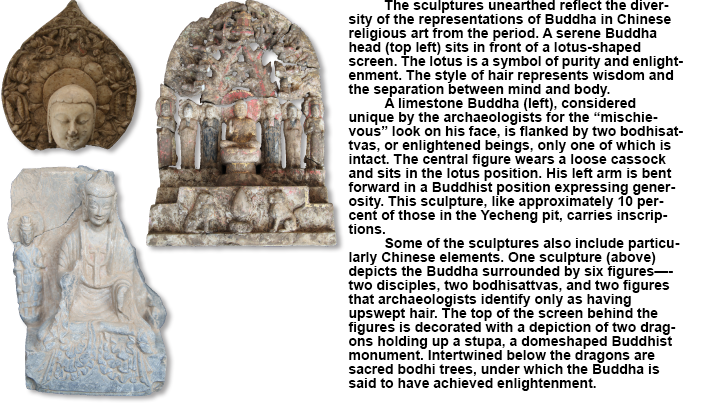

When Yecheng’s wealth was at its peak during the Eastern Wei and the Northern Qi (A.D. 550–577) dynasties, the city was dotted with Buddhist temples, some financed by the city’s wealthy families. Commissioning statues and other sculptures donated to temples in honor of family, friends, or rulers was a common practice. Even during this time, however, there were periodic backlashes against the religion. The first anti-Buddhism campaign started in a.d. 446, when the Northern Wei Dynasty emperor Tai Wudi ordered Buddhist monks to be killed and sculptures destroyed. In A.D. 574, during the Northern Zhou Dynasty, another emperor known as Wudi ordered that all monks abandon their temples. The harshest crackdown, however started in A.D. 841, when Tang Dynasty emperor Wuzong ordered the destruction of countless Buddhist temples.

At the recently discovered Buddha burial site at Yecheng, the majority of the sculptures were made before the city was razed in a.d. 580. A few, however, are from later dynasties, giving archaeologists a glimpse into life in a less powerful Yecheng. Han believes the sculpture deposit may have originated in the Tang Dynasty, when what was left of Yecheng was likely hit hard. The statues were obviously discarded during another attack on Buddhism, but it is not clear who threw them away outside the city. It could have been officials, following raids of local temples, or it could have been monks or citizens attempting to avoid official persecution. “They may have gathered up the statues that they had inside the city, taken them outside the city walls, and buried them,” Han says. “They would have used the same method to get rid of trash.”