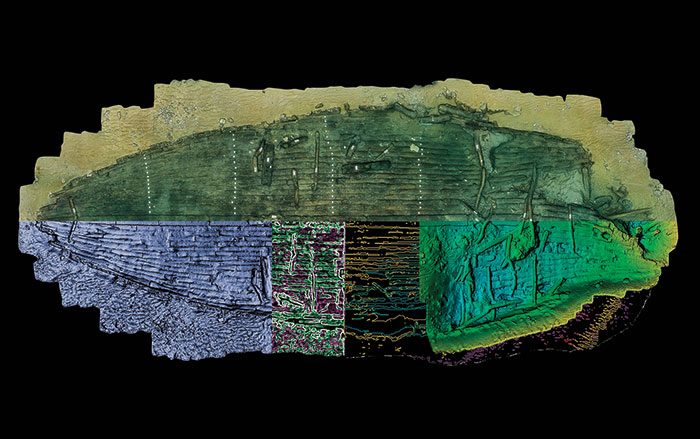

Ultramarine, a brilliant blue pigment, was so dearly coveted in the European Middle Ages that at times it fetched a higher price than gold. The coloring was prepared from the mineral lapis lazuli, which was mined at a single remote location in Afghanistan. A multidisciplinary team was, therefore, surprised to detect an abundance of ultramarine particles embedded in the dental plaque of a woman buried in the eleventh or early twelfth century at a German monastery. “We wondered how on earth a woman at this early date, in a kind of backwater location, came into contact with this incredibly expensive mineral,” says Christina Warinner, a molecular archaeologist at Harvard University and the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

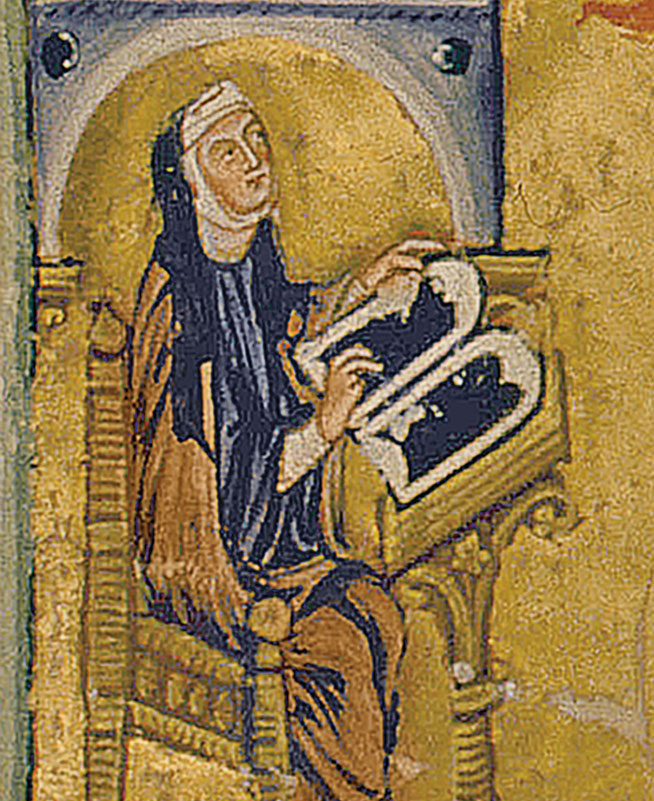

The most likely explanation, the researchers concluded, was that the woman was a scribe who used the pigment to illustrate sacred manuscripts. Their method of analysis may point the way to identifying more early medieval female scribes, who have gone unrecognized because they rarely, if ever, signed their work. “We do have a few surviving manuscripts written by women around the same time period,” says Warinner. “But how many more artists are out there waiting to be found if we just look at their teeth?”