On the 8:20 a.m. boat to Alcatraz, no one gawks at the spectacular views of San Francisco along the shore of the bay. It’s cold and overcast, as is typical for late spring. The conversations are familiar and collegial—this ferry is limited to people who work on the island, including National Park Service rangers, volunteers, and maintenance personnel. The 22-acre rocky island of Alcatraz is less than two miles north of downtown San Francisco, so the journey lasts only about 10 minutes. Since the maximum security Alcatraz Federal Penitentiary closed in 1963, after just under three decades of operation, the prison’s picturesque location and former celebrity inmates have generated reams of tourism-industry copy, inspired numerous Hollywood films, spawned urban legends, and made Alcatraz Island one of America’s most popular National Park Service sites. Yet few know about the island’s pre-prison history.

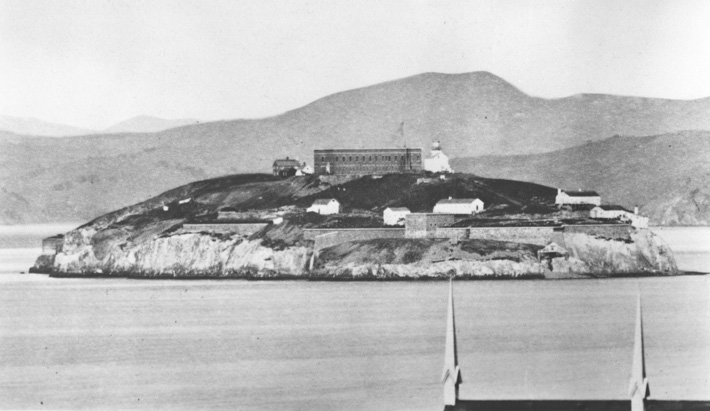

The first European to visit Alcatraz is thought to have been the Spanish explorer Juan Manuel de Ayala, who sailed his ship San Carlos into San Francisco Bay in August 1775 and named one of its islands Isla de los Alcatraces, “Island of the Pelicans” or “Strange Birds.” In the mid-nineteenth century, the island became home to Fort Alcatraz, one of the first U.S. military fortifications constructed on the West Coast. It was also the site of the West Coast’s first lighthouse.

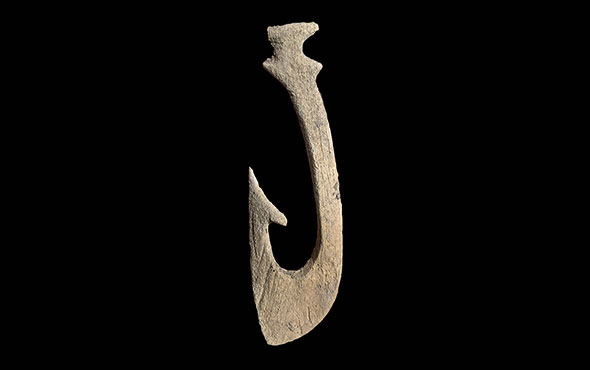

San Francisco Bay was formed only 10,000 years ago, as sea levels rose following the last Ice Age. Since then, the inhospitable Alcatraz Island has offered little to entice humans away from the temperate climate and abundance of natural resources on the mainland surrounding the bay. Except for an obsidian tool that archaeologists are nearly certain came to Alcatraz in imported soil, they have not found any artifacts dating from before Europeans first arrived in the late eighteenth century. An American army officer once described the island as “entirely without resources within itself and the soil is scarcely perceptible, being rocky and precipitous on all sides.” In 1847, Alcatraz’s first surveyor, W. H. Warner, wrote, “This Island is chiefly composed of irregularly stratified sandstone covered with a thin coating of guano. The stone is full of seams in all directions which render it unfit for any building purposes and probably difficult to quarry.”

On occasion, Alcatraz has been called White Island, most likely because of the bird droppings covering it. “There was nothing here, just a desolate rock in the middle of the bay covered in bird guano,” says archaeologist Peter Gavette, one of the passengers on the early morning ferry. Gavette is responsible for managing the cultural resources of the 130-square-mile Golden Gate National Recreation Area (GGNRA), of which Alcatraz is a part. Over the past decade, he has been part of a team from a wide range of institutions specializing in geophysics, geology, architecture, and preservation, led by Timothy de Smet, director of the Geophysics and Remote Sensing Laboratory at Binghamton University, that has scientifically explored one of America’s most (in)famous islands. In particular, the team has searched under the prison’s recreation yard for the defensive walls and traverses—protected passages connecting different gun positions and magazines—that were covered over during construction of a military prison, which was completed in 1912. Using noninvasive techniques including ground-penetrating radar, terrestrial laser scanning, and computer-generated 3-D reconstruction, they have revealed some of the secrets lying just beneath Alcatraz’s well-trodden surface.

The techniques used at Alcatraz may help archaeologists learn more about other important sites without disrupting the soil or structures. Mark Everett, a near-surface applied geophysicist at Texas A&M University, worked with de Smet at Alcatraz and on several other archaeological projects. “Geophysics is widely used among archaeologists because it gives you a map of the cultural resources without having to destroy anything,” he says. “The idea is that you look for disturbances associated with past human activity and then see what you find. That’s what geophysicists do; whether it’s oil exploration or looking for gold, we put the X on the map.”

Mexico ceded California to the United States in 1848, after the Mexican-American War. That same year, the discovery of gold at Sutter’s Mill, about 130 miles northeast of San Francisco, set in motion a series of changes that dramatically transformed the city almost overnight. According to Gavette, in 1847, the dusty, muddy shantytown of tents and wooden structures then known as Yerba Buena—the city’s name was not officially changed to San Francisco until later that year—had a population of just 459. In 1849, 50,000 people arrived on their way to seek their fortune. The shantytown, which had been ravaged by multiple fires, was replaced with solid buildings made of brick and stone, their construction fueled by the flow of money from the gold fields, explains Gavette.

By 1860, San Francisco was the fifteenth largest city in the United States and the largest west of the Mississippi. “Ships would arrive and lose their crews to gold fever and lay empty or be reused for storehouses, hotels, and jails in the cove,” Gavette says. “This area was ultimately filled in and became the reclaimed land in what is now the Financial District.” These ships’ hulls, which once served as shelters, are still being uncovered today on construction sites in what is one the West Coast’s leading commercial centers.

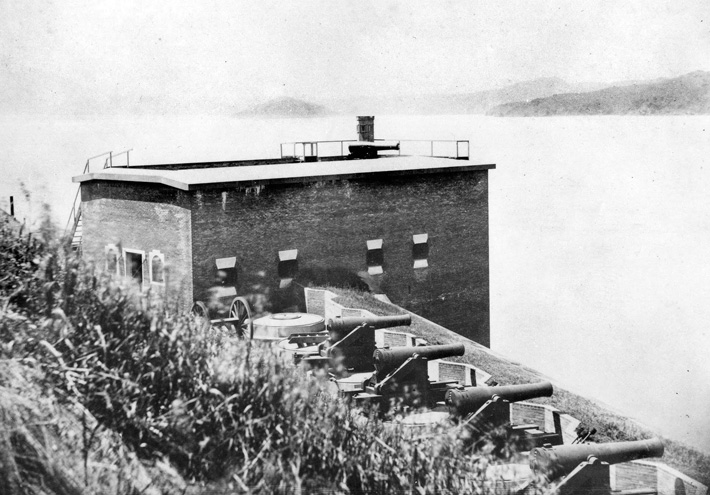

The commercial and trade boom that resulted from the Gold Rush demanded that the Union’s newest state be properly defended. California was the first state on the Pacific Coast, and as the Bay Area’s strategic importance increased, the need for defense grew even greater. Construction of Fort Alcatraz began in 1853, and its first military fortifications were intended to defend the bay against maritime attack. While not very welcoming in terms of weather or landscape, Alcatraz Island nevertheless occupies a key strategic location. One hundred and eight heavy cannons were mounted along the fort’s walls, designed to prevent hostile vessels from passing through the Golden Gate, the strait that connects San Francisco Bay to the Pacific Ocean. Potential threats included foreign attackers, and, not long after, as the first rumblings of the Civil War were heard, Confederate raiders or their affiliates intending to disrupt commerce, engage in piracy to fund the southern insurrection, inflict military damage, and generally sow chaos along the West Coast.

When the passengers disembark from the ferry at 8:30 a.m., the wind feels much sharper than it did on the mainland. On the narrow paths between buildings, the frigid gusts carry the smell of guano and seaweed. Volunteers have landscaped the island with brightly colored flowers in a more-than-century-old tradition dating back to the days of the fort. Cleaning crews spray the rocks with high-pressure hoses—the island contains protected nesting grounds for seven species of seabirds, and a lot of droppings accumulate.

The only structures built on the island since the closure of the prison are a bookstore and bathrooms. On arrival, every visitor must pass through the fort’s former sally port, the heavily fortified entrance where rifle slits once defended against possible invaders advancing up the main road from the wharf and into the fort. Below the sally port and in front of the guardhouse is a defensive dry moat and a basement cell used to hold prisoners, both military and civilian, starting in 1859. These included the crew of the schooner J. M. Chapman, perpetrators of the first and only attack executed in California by Confederate sympathizers during the Civil War era. In 1863, the Knights of the Golden Circle, a shadowy secret society with the stated goal of annexing all of Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean to form a proslavery “Golden Circle” in conjunction with the Confederacy, formed a plot to arm the schooner and raid vessels along the Pacific Coast. On the night before it was due to set sail, J. M. Chapman was seized by the U.S. Navy after its captain bragged about the scheme in a local tavern.

Farther up the road from the guardhouse is the lighthouse, which was moved to its current location in 1877 and rebuilt in 1909 after sustaining some damage in the 1906 San Francisco earthquake. Next to it is the prison’s main cell house, which is the largest building on the island. It was the fort’s citadel until that structure’s upper two floors were torn down to build the cell house. The citadel, which was once reached by a drawbridge, was the fort’s main military building and was equipped with three-foot-thick masonry walls. It is the only known nineteenth-century defensive fortress on the West Coast whose walls were strong enough to resist both rifle and shell impacts, as well as infantry attacks. Its storerooms, privies, and a complex of water cisterns remain under the prison but are off-limits to the public. When the citadel was converted into officers’ quarters in 1882, three prison cells in one of the towers were closed off, dumbwaiters were installed, and windows were punched through the walls. Six kitchens and six servants’ rooms were created in the basement. The army, though, still occasionally used the old basement as dungeons, or “dark cells” for unruly prisoners. The Federal Bureau of Prisons used the cells for the same purpose, but ceased doing so around 1938. Underground magazines once used to store arms and ammunition remain intact. An underground tunnel 180 feet long was drilled in 1873 to allow secure communications across the northwest end of the island from the vicinity of the North Caponier, a masonry structure that could provide flanking fire, to Batteries 1 and 2. From there, the tunnel leads to the bottom floor of the prison-era New Industries Building, which was built in 1940.

By 10 a.m., the first of an average of 4,000 daily visitors have arrived. All tours are taken with audio headsets, so the scene in the main cellblock is somewhat surreal, as thick crowds of visitors wander the enormous main hall of the prison in total silence. Passing through a brick tunnel at the bottom level of the former citadel, which is not accessible to the public, Gavette dismisses the pop-culture Alcatraz hype. “These passages have contributed to a lot of the theories about hidden dungeons and tunnels on Alcatraz,” he says. “All the movies with fantastical stories of escapes and all the hidden, mysterious places—it’s really the result of misunderstanding the construction history and the fact that a portion of the citadel was left intact below the cell house, a location that most visitors don’t see.” Some of these misconceptions also date back to early twentieth-century media accounts that falsely described the foundation of the citadel as the relic of a prison built by the Spanish.

On the side of the hill below the recreation yard and the cell house that overlooks the bay, Gavette stands in a field of bright yellow and magenta wildflowers. He points to a steel door in the side of a concrete base, which provides entrance to one of the fort’s magazines. High-velocity rifled cannons deployed during the last half of the nineteenth century were capable of quickly damaging and destroying masonry-walled forts. Several of these, such as Forts Morgan and Sumter, were destroyed during the Civil War. But new types of artillery had the capacity to shatter even brick and stone fortifications, spraying shrapnel at soldiers in the batteries. At Alcatraz, this danger was compounded by the steep slopes of rock behind the batteries, which were liable to explode on impact and shower down on the defenders. Military engineers thought it was better for the guns to be more widely spaced and protected not by rigid walls, but by mounds of earth that would absorb the force of the incoming ordnance.

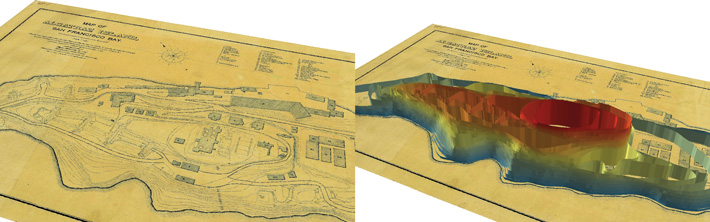

“Due to the improvements in armaments, including rifled cannons with increased velocity that shattered the vertically walled masonry forts on the East Coast during the Civil War, military engineers started placing soil in front of the defensive walls to absorb the impact of the artillery,” Gavette says. The parts of Alcatraz Island that were altered most noticeably are two large, conspicuously flat areas, which became the parade ground and the penitentiary’s recreation yard. “This is really dramatic when you compare and contrast the 3-D reconstructions and visualize the changes,” he says. But military engineering could not keep pace with technological advances in artillery and munitions, and, says Gavette, Fort Alcatraz’s defenses were more or less obsolete by the end of the Civil War, just over a decade after they had been constructed. By December 31, 1901, according to the annual armament report, the last of the fort’s 108 cannons were gone.

In 1969, six years after the prison was closed and the island was abandoned, activists from the American Indian Movement (AIM) came to Alcatraz as part of a symbolic occupation that soon became an actual occupation that lasted 19 months. The movement wanted to symbolically claim the island as a protest against U.S. policies toward Native peoples. During the occupation, some 100 activists organized themselves into a community and lived in abandoned buildings on the grounds, including apartments on the parade ground that were once inhabited by prison personnel. When the protesters left in June of 1971, the General Services Administration destroyed these structures rather than risk having them reoccupied. Much of the parade ground today is covered with rubble resulting from this destruction that has sat undisturbed for almost 50 years. “It’s very expensive to get it off the island,” says Gavette. All that remains of the occupation is some of the AIM occupiers’ graffiti, which has been restored and repainted by the National Park Service in an effort to preserve the movement’s legacy.

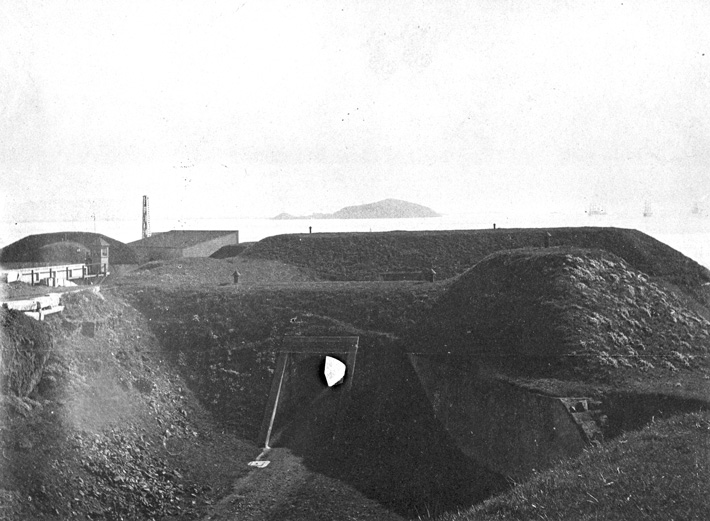

The recreation yard where prisoners exercised and played horseshoes and handball also conceals its own story. This is where the archaeological team focused their efforts to locate underground structures. Gavette explains that they were attempting to find whether there were any remnants of the “Third System” fortifications—a nationwide series of masonry forts built as part of a seacoast defensive plan funded by Congress from 1812 to 1867. It was the first American fort system to employ standardization in design and planning and represents an important transition in military construction techniques from vertical brick walls to reinforced earthen structures.

Unlike Fort Alcatraz, most Civil War–era military fortifications were destroyed during that war. “We don’t have a representative idea of what those structures looked like in general throughout the country, and at Alcatraz, we didn’t even know if they still existed,” says Binghamton University’s Timothy de Smet. “One of the amazing things we found by integrating the data from terrestrial laser scanning and ground-penetrating radar was that not only are the traverses still there, but that they are incredibly intact and right beneath the surface, six inches below your feet.” The team also discovered how these elements had been altered over time. At some point after they were built, the traverses were coated with a thin layer of concrete. “We think that that was due to wind and erosion, and that the earthen traverses would have melted if they hadn’t put that layer of concrete on,” de Smet adds.

At Fort Cronkhite, less than 10 miles north of the Golden Gate, the archaeological lab and storage facility for the GGNRA—and Peter Gavette’s office—is located on a secluded stretch of beach in the former U.S. Military Enlisted Men’s Club. All artifacts found at Alcatraz are processed, cataloged, and stored here. The Military Enlisted Men’s Club is a wooden structure built in 1940 during the rapid military buildup for World War II, and a large hall still contains the stage where musicians performed for the Coast Artillery Regiments that operated the 16-inch gun batteries nearby. Here the men played table tennis, drank beer, and danced with women bused in from nearby Sausalito.

Most of the enormous room is filled with six-foot-high flat file cabinets for storing artifacts. Each drawer of artifacts from Alcatraz holds carefully labeled objects, mostly dating to the prison era, including plastic bags full of handballs, metal horseshoes, and small plastic and glass toys used by guards’ children. One drawer is entirely filled with battered tin cups, glass jars, and soda bottles. Wood pallets on the floor hold cannonballs, large artillery shells, corroded ship parts, and other objects that don’t fit in the drawers. Some of the cannonballs were found in Kirby Cove, directly north of San Francisco, having been shot across the Golden Gate for target practice from Fort Point, which is located under the southern span of the Golden Gate Bridge and which was established around the same time as Fort Alcatraz. In black-and-white photos from the days of Fort Alcatraz, women in long dresses pose sitting on piles of cannonballs neatly stacked in geometric patterns.

On the stage are heavy metal cabinets of drawers from which Gavette removes large historical military maps printed on Tyvek that he has copied from originals at the National Archives. Looking at the rich variety of dates, angles, and directionals, it’s hard to imagine many other places that have been so precisely analyzed and documented in such detail over such a long period of time. Gavette explains that a great deal of work is now being done to georectify old maps and aerial imagery on top of new maps to see if changes over time might be identified. Georectification is a process by which images, including aerial and satellite photographs, geophysics data, or scanned maps, are coordinated in order to determine the exact location of structures or landscape features. The technique is especially helpful for visualizing how places change over time, particularly when building remains are absent or overgrown, or when the topography of an area itself has shifted due to human intervention or natural events. “We’re lucky to have a wealth of cartography for the island because of its military history, so we are able to look at it through multiple layers and levels,” Gavette says.

In his office, which adjoins the main hall, Gavette demonstrates the GIS software used for cartographic analysis and reconstruction. The program can display elevations visually using varying colors. Historical buildings can be added or removed. In this way, the spatial relationships and topographical changes between current ground surfaces and previous constructions can be readily perceived and evaluated. Using similar technologies, Gavette hopes to create a virtual-reality experience for visitors. “With all the buildings that have been on the island and that are no longer there,” he says, “it would have looked much different than what you see now.”