From the twelfth to the seventeenth century, the MacDermots ruled the kingdom of Maigh Luirg in the Irish province of Connacht from a small island in Loch Cé (now Lough Key) known as the Rock. They were the right-hand men—and sometime rivals—of the O’Conors, the kings of Connacht, whose power center lay at the modern village of Tulsk, some 20 miles away. It was Diarmait, king of Maigh Luirg from 1124 until his death on the Rock in 1159, who gave the MacDermot clan its name.

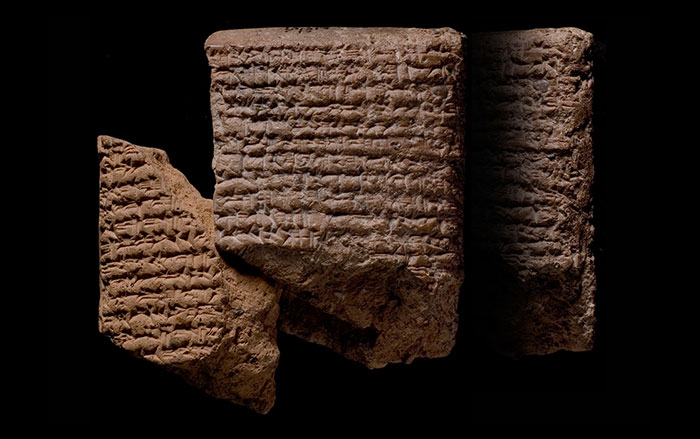

In the sixteenth century, the king Brian MacDermot commissioned the Annals of Loch Cé, which remain among the most important written records of medieval Irish history. They are the primary source for the history of the kingdom of Maigh Luirg (Anglicized as Moylurg), which occupied roughly the same territory as the northern section of the modern county of Roscommon. The Annals, which survive in only two manuscripts written primarily in Early Modern Irish, with some sections in Latin, were compiled using earlier Irish annals as sources. They record more than five centuries of political, ecclesiastical, and military events, succession and land disputes, and even notes on the weather. They begin with the Battle of Clontarf in 1014, a contest that pitted Brian Boru, the high king of Ireland, against a coalition composed of the king of Dublin, Sigtrygg Silkbeard; the king of Leinster, Máel Mórda; and a force of Vikings from across the region. The Annals end in 1590, when most of the Gaelic families in Ireland, including the MacDermots, were thrown off their lands by the Anglo-Normans—the ruling class of England after the Norman Conquest in 1066—who had invaded Ireland centuries earlier, in 1169.

Surprisingly, there are relatively few references to the Rock of Loch Cé itself in the Annals, or in other contemporaneous historical works. In 1187 (or 1184, scholars are not certain), the Annals record that lightning struck the island, causing a fire. In 1207, the king Tomaltach MacDermot died on the Rock. A further reference is made to a siege of the island in 1235 by an Anglo-Norman force. During the attack, the invaders used siege engines called perriers and fireboats made from demolished wooden houses. The siege forced the MacDermots to abandon the island for a decade. Then, over the next three and a half centuries, the Annals record periodic attacks on the Rock, countless clashes over succession, and the deaths of numerous MacDermot kings. But with only one exception—the mention of a “great, regal house” that was built on the Rock in 1578 by Brian MacDermot—nowhere are the buildings of a royal residence ever described.

The sand-colored stone walls, turrets, and empty windows that can be seen on the Rock today, though picturesque, are not the remains of a MacDermot stronghold, but a product of the imagination of John Nash, the nineteenth-century Welsh architect of Buckingham Palace. In the seventeenth century, an Anglo-Irish noble family named the Kings took possession of the Rock. More than a century later, Robert Edward King commissioned Nash to build the Gothic-style folly, the ruins of which are now visible on the Rock and on guidebook covers, restaurant walls, and travel posters. But it is the MacDermots’ much earlier castle—hidden, perhaps, by crumbling walls, creeping vegetation, and feet of mud—that archaeologist Thomas Finan of Saint Louis University has now set out to find.

Finan and his team are searching not just for the remains of walls, but for an entire way of life. Scholars know very little about how the Gaelic kings lived, and what they do know derives primarily from Irish annals and other historical sources, many of which carry the bias of the Anglo-Norman rulers hailing from the opposite side of the Shannon River, which splits the west of Ireland from the east. So little is understood about the kings of Maigh Luirg—and other royal families, including the O’Conors, O’Flahertys, and O’Reillys—largely because Irish archaeology has been dominated by the study of Neolithic, Iron Age, and early Christian Ireland, as well as Anglo-Norman castles, which, unlike Gaelic sites, are easily identifiable in the landscape. And, over the past three decades, urban archaeology tied to construction projects has skewed the evidence in favor of medieval city dwellers who were not, it seems, the lords of the country.

Furthermore, unlike the Anglo-Normans, the Gaelic kings did not keep detailed estate inventories and accounts. Coupled with the absence of archaeological evidence to the contrary, this has tempted many scholars of medieval western Ireland to agree with the twelfth-century historian Giraldus Cambrensis, who argued that the Gaelic kings did not build castles. Whether Giraldus’ words were a poorly disguised attempt to portray the Irish as uncivilized in contrast to his Anglo-Norman patrons, or an accurate appraisal is debatable. “Giraldus wrote that the Irish were all living in timber huts and went into battle with little or no armor,” says Finan. “‘They don’t build castles, they don’t do this, they don’t do that’—and this narrative was accepted until things started to change a few decades ago.” In fact, explains Finan, no high medieval power center, or caput, from the Latin for “head,” of which there are many in the west of Ireland, has ever been fully excavated. At Lough Key, Finan and his team are just starting to create a picture of what a residence for a family as high status as the MacDermots—their castle—might have looked like. “We aren’t rewriting history here, we are writing it,” says Finan. “We can now start to link the archaeology to these historical sources. It’s really starting to happen. This site is like a text to me, and the archaeology is creating the narrative.”

In 2007, archaeologist Niall Brady of the Archaeological Diving Company undertook the first underwater archaeological survey of the waters around the Rock. He wanted to find out whether the island is a natural one or an artificial crannog, as well as what types of archaeological material lay on the lakebed. Brady’s team found that the western half of the island was naturally formed of rocks and large boulders. He had expected to identify timber pilings or other indications that, like its eastern half, the entire island was artificially constructed. “In this way the site is unusual in Ireland because, unlike most lake islands, it isn’t a crannog per se,” says Brady. The team also recorded a great deal of animal bone, some of it butchered, along with more recent champagne bottles and other debris that can, says Brady, be assigned to the feasts of nineteenth-century—not medieval—lords.

EXPAND

The Castle of Heroes

The modern poet W.B. Yeats (1865–1939) was one in a line of centuries of Irish bards who, like the personal poets of the MacDermot kings, wrote about the Rock of Loch Cé. Yeats called the Rock the “Castle of Heroes” and envisioned it becoming a utopian community that would function as a kind of living shrine to the Irish past and a place to practice what he termed “a ritual system of evocation and meditation to reunite the perception of the spirit of the divine, with natural beauty.” In his description of this ritual system, Yeats combined his worship of the mystical might of Ireland’s past and his belief in the occult with his political agenda—in particular, Irish nationalism and an ardent desire to drive the English from the country.

Medieval Irish poets, too, had functions and powers beyond pure entertainment and delved into both religion and politics. “The medieval Irish bards were the tabloid reporters of their day,” says National University of Ireland Galway archaeologist Daniel Curley. In addition to reciting traditional songs, poems, and myths, medieval Irish bards were kingmakers—and breakers. “There were praise poems and satirical poems,” explains James Schryver of the University of Minnesota Morris, “and your greatest fear as a king is that your poet will satirize you and make it clear that you are no longer fit to be king.” Incidentally, adds Schryver, a poet could also raise blisters on the king’s face through his recitations. In the Middle Ages, as for Yeats, there was political power—and magic—in the words of poets.

At the same time, Finan, Brady, and Kieran O’Conor of National University of Ireland Galway surveyed the remains on the island, which had just been privately acquired and cleared of vegetation, making the ruins more visible than they had been in a century. O’Conor concluded that there was evidence for a tower house, which was recognizable by the presence of windows and arrow slots, two well-known features of such structures. Tower houses, common at later medieval lordly sites, were multistory fortified residences built at a time when the ruling classes of Ireland both west and east lived in fear of what they perceived as generalized lawlessness and danger posed by their subjects. Although it is known that these secure structures were built in locations where Gaelic lords already had settlements, “people were surprised about the Lough Key tower house,” says archaeologist James Schryver of the University of Minnesota Morris, who is part of Finan’s team. “They didn’t expect it to be there.”

Finan thought that the tower house had been built in the Late Middle Ages (A.D. 1200–1450) and wasn’t able to identify any earlier structures on the Rock. It seemed that, despite the centuries-long prominence of the MacDermots, they had had no castle at their lordly residence, or even a large building, until the construction of the tower house. Perhaps the island had only been lightly defended with timber fortifications or a simple stone wall in the High Middle Ages (A.D. 1000–1200). Perhaps all the high medieval castles in Ireland were built in the east and the south by the Anglo-Normans. Perhaps Giraldus Cambrensis had been correct all along. But Finan had his doubts. “You could explain the absences either by saying Giraldus Cambrensis was right or, more interestingly, by saying maybe he was right in one sense, in that the Gaelic lords didn’t live in traditional European castles, but that that doesn’t mean they didn’t build well-fortified stone structures and have their own architectural language. He didn’t actually see what they were living in, and didn’t pick up on the fact that their language of power and authority was different.”

It is clear, for example, judging from the copious stone monasteries and churches that were constructed at the time, that the Gaelic lords were more than competent builders. “One of the key features of Irish lordship and one of the ways you achieved legitimacy was by building on the landscape,” says Finan. Exactly what the medieval Gaelic kings were building is an open question. In Anglo-Norman Ireland, and across medieval France, Germany, and the Holy Land, kings, lords, and Crusaders constructed the type of large, walled, often moated fortified stone buildings that immediately come to mind with the mention of a castle. “Those types of castles are intimately tied to and are a function of the social structure of those places, which is to say, feudalism,” says Finan. In medieval Europe, the feudal system governed the relationships between the king and nobility, and between the nobility and peasants with respect to land tenancy, serfdom, and the exchange of lands for military service, all of which were centered on the castle.

However, explains Finan, feudalism was not the dominant social system in western Ireland, including Connacht, which remained in Gaelic hands. Instead, there were multiple kings at one time and professional classes of historians, clerics, lawyers, and poets, along with the peasants who worked the land. “If you are looking at the whole landscape of high medieval Ireland, it includes these dynastic professions, one of which was a learned class of historians who composed works like the Annals of Loch Cé,” says Finan. One such family of historians, the O’Malconnors, was set up in a settlement south of the Rock and became part of the MacDermots’ retinue. “I thought, what is an Irish castle, if one were to be found?” says Finan. “Does it look enough like a European castle to call it a castle, but reflect an entirely different social structure that is native and local?”

With this in mind, Finan returned to Lough Key in 2018. “We have this high-status site that’s very visible, but actually not all that well known,” says Finan. “It’s mentioned in the Annals and it’s surrounded by three important monasteries located on other islands in the lake, by agricultural fields, and a church—all the hallmarks of the Middle Ages—but where was everyone, including the kings, living?”

The first step was a geophysical survey of the island’s western side that detected the presence of buried structures, including a possible floor surface or entranceway. The following year Finan began to excavate. He was concerned that the builders of the nineteenth-century folly had scraped the island clean and thrown everything—much of which Brady had seen in his underwater survey—over the side before leveling it out for the new construction. “We anticipated having to dig through mounds of nineteenth-century construction fill and stone,” says Finan. But the fill wasn’t nearly as deep as he expected, and what the folly builders had actually scraped off were the remains from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, no evidence of which was found apart from a single pipestem. “Six inches from the surface, and we were in the Middle Ages,” says Finan.

In their first excavation season, Finan’s team uncovered evidence of what he believes was the MacDermots’ castle. This includes two possibly high medieval structures, one with a clay floor, and, underneath the buildings, what may be the entranceway that was part of an earlier fortification suggested by the geophysical survey. The archaeologists have also found that the stone wall surrounding the island appears to have had three or even four phases, the earliest of which predates the structures. Taken together, their finds are beginning to suggest the presence of a large stone fort with a 10-foot-wide wall that may have had a much higher timber superstructure. This wooden feature may have accounted for one of the numerous fires recorded in the Annals, evidence of which Finan’s team has identified in the ground, in the form of bits of burned wood. As surprising as the identification of the Rock’s tower house may have been, the discovery of signs of a castle has been much more so. It seems the MacDermots may indeed have built, lived in, and defended an Irish castle. “It changes everything,” says archaeologist Daniel Curley of the National University of Ireland Galway. “Gaelic archaeology needs a reset button because there are still so many basic questions about culture, lifestyle, and economics. To have excavated a lordly site is massive.”

In addition to monasteries, castles, and agriculture, other integral elements of medieval European life included feasting, hunting, games, and poetry and genealogy recitations. (See “The Castle of Heroes.”) Late sixteenth-century woodcuts by the English artist John Derricke show scenes of Gaelic life that include Irish lords feasting, although they are depicted doing so outdoors, not in a hall or castle. Like Giraldus Cambrensis, however, Derricke likely sought to promote a negative vision of Gaelic lordship. Feasts are mentioned in such sources as the medieval national epic, the Cattle Raid of Cooley (see “Medieval Cattle Raiders”), and in this and other myths a good leader is measured by his generosity, including sharing the best cuts of meat. “This isn’t a world for introverts,” says Schryver. “Kings have social duties, including hosting feasts, and you aren’t going to make it if you don’t.” Until the recent excavations on the Rock, very little archaeological evidence of feasting had been found at any Gaelic lordly settlement. Now, however, Finan’s team has uncovered a vast amount of pig and cow bone, including many joints providing evidence that the kings saved the choicest cuts for their feasts. In the medieval period, as it does today, the mostly rural county of Roscommon had some of the most fertile land in Ireland, and the wealth of the Irish kings, much as the wealth of the modern county, lay in cattle. The kings used cattle as a food source and for raw materials, of course, but the animals’ importance transcended the utilitarian. “Cattle are the coin of the day, the means to buy high-value and high-status gold objects,” says Schryver. “They are also the way status is measured and conferred.” Farmers were ranked according to how many head of cattle they owned, and categories of wealth were established using, for example, the value of a female slave or of so many head of cattle, which varied depending on whether the animals were cows or more valuable bulls.

Along with the pig and cow bones, Finan’s team has found a tusk from a very large boar that was likely hunted on MacDermot lands and then taken to the Rock to be butchered and eaten. The team has also identified fish bones, more evidence of what the MacDermots were eating. “Now we will be able to say something about the dietary habits of the high-class Irish lords, which is something we have never been able to do before,” says Finan.

EXPAND

Medieval Cattle Raiders

It was not enough for medieval Irish lords to own cows, they also had to steal them. “Stealing cows was important in this society,” says archaeologist Daniel Curley of the National University of Ireland Galway. “It was a ready source of wealth, a slight to opponents’ honor and power, and a pseudo-martial sport.” In fact, pilfering the animals is the central theme of Ireland’s national epic, the Cattle Raid of Cooley, which was composed in the seventh and eighth centuries. It tells the tale of a conflict between the kings of Connacht and the kings of Ulster over the Brown Bull of Cooley, which was owned by Daire, an Ulster chieftain.

Medb, the warrior queen of Connacht, and her husband, the king Ailill, were very competitive about their assets, explains University of Minnesota Morris archaeologist James Schryver. “Much of their pillow talk involves arguing about their possessions, including which of them has the best bull.” Ownership of an impressive white-horned creature named Finnbhennach wins Ailill the argument. Determined to be richer than her husband, Medb plans to steal the famous brown bull from Daire and leads her army from Connacht to seize the animal. To settle the score, the teenage hero of Ulster, Cuchulainn, meets Medb’s greatest warrior—and Cuchulainn’s closest friend—Ferdiad, in combat. After four days, Cuchulainn wins the contest, defeats Medb’s army, and captures the brown bull. In the end, the brown bull vanquishes Finnbhennach—after which its heart bursts and it dies—and peace is finally declared.

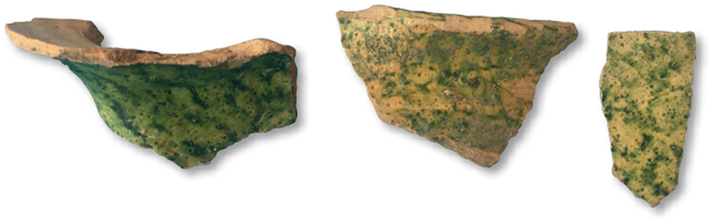

Another lacuna in the archaeological evidence of high-status medieval Ireland has been objects of daily life, or even of special events. “It’s amazing how few artifacts there are at most sites,” says Finan. “This has played into the narrative that there is nothing to find—but maybe we haven’t been looking in the right places.” Chief among these absences has been pottery, the mainstay of archaeological artifacts. “It’s very strange that after the Bronze Age there is so little pottery until the very late medieval period,” says Curley. “We know they are using it, or think they are, but where is it?” At Lough Key, however, Finan’s team has discovered thirteenth-century green-glazed pottery, a type rarely if ever found at a medieval Irish site, that was used for drinking wine. The pottery was discovered sealed in clay under a burn layer dating to 1320, when the O’Conors set fire to the island during one of their regular clashes with the MacDermots. The vessels, along with the wine, may have been imported through the English city of Bristol. “Having this kind of pottery and drinking imported wine is evidence of the MacDermots’ adopting a status symbol well-known in the Anglo-Norman world,” says Schryver. “This isn’t out of the Irish milieu, but maybe they did it for particular guests to whom owning such items would have been impressive. At the most basic level, it’s also evidence that the kings were able to access trade networks that we weren’t aware they were part of.” In contrast, a silver pin found by the team is traditionally Irish, as are several other artifacts, including a bronze pin, a gaming piece, and a bone comb. Clearly the Irish kings sought to balance fidelity to their own culture and identity with a desire for imported objects and traditions that may have been both politically and financially advantageous.

The MacDermots’ contact with the world outside Connacht was also brought into focus by the discovery of a late thirteenth- or early fourteenth-century English silver penny that, says Schryver, challenges the entire story of how the Gaelic kings interacted with the Anglo-Normans in Ireland. “If you follow the dominant discourse about Gaelic Ireland up until the last decade—and even to the present in some fields—the idea is that the Gaelic kings weren’t interacting with the Anglo-Normans at all, that they were separate, and also at war with them, so they shouldn’t be using their money.” But the penny, combined with a similarly dated one found on MacDermot lands nearby, and others found at the ecclesiastical complex of Kilteasheen just eight miles away, make it clear that these English coins had made their way into the landscape. “Every trowel scrape reveals something we didn’t know,” says Schryver, “or makes us question something we thought we knew.”

The MacDermots, like all the other medieval Irish lords who were their sometime allies and sometime enemies, found themselves in a precarious position. On one side, just across the Shannon, were the Anglo-Normans, who made regular incursions into Gaelic territory. Closer to home were the O’Conors, O’Kellys, O’Dowds, and other families, all vying with each other for control. To fortify their claim to power, the MacDermots needed a castle, one that reflected their own social structure and values. “They could probably see that everyone else was building castles,” says Schryver, “and, because they were quite quick on the uptake, they understood not only the practical but also the symbolic value of having a castle.” Finan is now confident that he has uncovered evidence of just such a fortified medieval castle on the Rock of Loch Cé. “The Gaelic kings don’t give up their secrets easily,” says Finan. “We have to go and find them.”