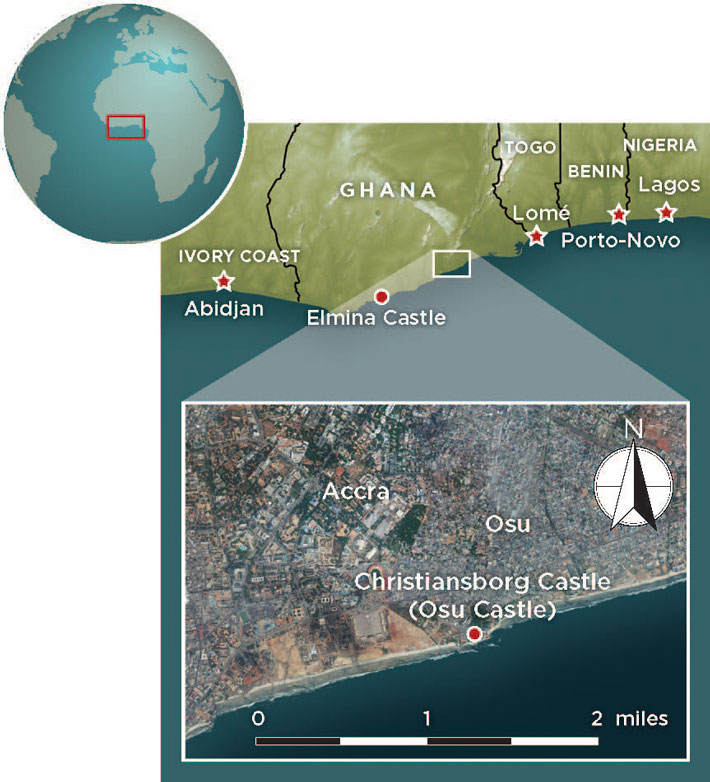

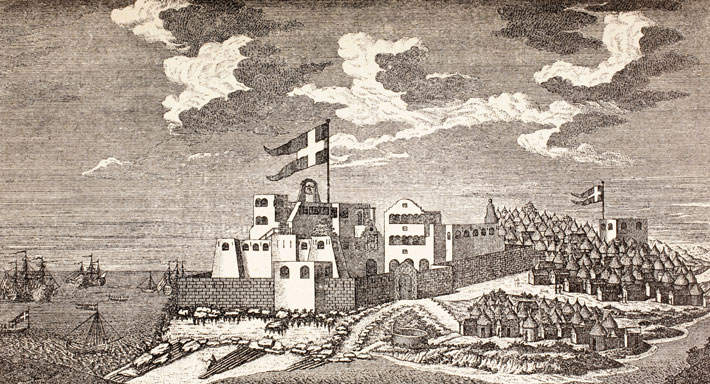

Along a stretch of the West African coast known to European explorers and traders as “White Man’s Grave” due to its association with death from malaria, yellow fever, dengue, and heat exhaustion, Danish soldiers and merchants built a fortified structure called Christiansborg Castle in 1661. The building survives to this day in what is now the city of Accra, Ghana, where it is known as Osu Castle, after the district in which it stands. Since 2014, archaeologists led by Christiansborg Archaeological Heritage Project director Rachel Ama Asaa Engmann have been working at the castle. They have uncovered evidence of a Euro-African community made up of European men who worked at the castle, African women they married, and the children of their unions. The primary business in which this community was engaged was the transatlantic slave trade. With only a few brief interludes, from the construction of the fort until 1803, when Denmark began to enforce its abolition of that trade, an estimated tens of thousands of enslaved people were held in Christiansborg Castle’s dungeons before being taken to the Danish West Indies, which included the Caribbean islands of Saint Croix, Saint John, and Saint Thomas. At least 100,000 captives were transported during the Danish transatlantic slave trade.

Europeans began formally trading with West African peoples in the last quarter of the fifteenth century, nearly 200 years prior to the construction of Christiansborg Castle. The Portuguese built Elmina Castle, the first permanent European trading post in West Africa, on the same stretch of coast as Christiansborg Castle, some 85 miles west, in 1482. Over the next 300 years, European nations, including Portugal, the Netherlands, England, France, Spain, Sweden, and Denmark, constructed around 80 castles, forts, and trading lodges within the borders of modern Ghana alone. This territory represents a fraction of the entire region of West Africa where Europeans traded with African groups and acquired captives, a massive area Europeans called Guinea, which stretched from roughly modern Senegal to modern Gabon.

In the late fifteenth century, Europeans encountered a diverse and ancient sociopolitical landscape in West Africa. “You are looking at a region that had developed a very sophisticated organizational network of cities, kingdoms, emerging states, and full-fledged states,” says archaeologist Akin Ogundiran of the University of North Carolina at Charlotte. “People had extensive political structures, and the region was thriving and bustling politically.” West Africans were accustomed to interacting, and even intermarrying, with people who looked different from them and spoke different languages, including Arabs and Berbers. “The only difference is that Europeans were coming across the ocean instead of across the Sahara,” says Ogundiran.

In the mid-seventeenth century, the Ga people of Ghana lived in and controlled the area where the Danes built Christiansborg Castle. However, not unlike much of Europe during the period, land regularly changed hands through warfare and intermarriage intended to solidify political alliances. The Ga’s rival for political supremacy in the region around Christiansborg at the time was a group called the Akwamu. “The Akwamu and other ethnic groups also sent royalty and emissaries to the coast because Europeans were there,” says Engmann. “They, too, wanted access to trade.”

Christiansborg’s Euro-African community, Engmann and her team are discovering, reflects a system of trade and cross-cultural exchange that had matured along the coast of West Africa by the seventeenth century. When Europeans first arrived, they brought objects that appealed to West African elites, including silk and satin textiles, glass beads, carpets, and bangle bracelets. Later, they introduced flintlock muskets and products from plantations in the Americas, including tobacco and rum. These goods became highly sought after and could be traded for large numbers of captive Africans. However, Engmann says, contrary to the misperception that Africans consumed any and all products the Europeans brought, European traders often shipped in goods that local people actually did not need or want. Fashions for textiles in particular changed rapidly. Wares would regularly be stored indefinitely as dead trade or otherwise go unsold.

At Christiansborg Castle, the Danes created a cosmopolitan settlement, where Euro-African families furnished their homes with goods from Europe, Asia, the Americas, and across the African continent. Contemporaneous written accounts suggest that the children of Danish men and African women formed complex personal identities, sometimes traveling to Copenhagen to be educated and often working for Danish interests at Christiansborg Castle while still maintaining a strong connection to the local Ga community. The design of the castle, with its cannons facing both out to sea and toward the interior, is evidence of the violent atmosphere of the time. Competition for supremacy in the transatlantic slave trade raged among European nations.

In their seven years of digging, Engmann’s team has worked to uncover the large precolonial settlement in the present-day garden area inside the castle walls. “Unlike in the Americas, when we say ‘precolonial,’ we mean before the British colonial period—not before contact with Europeans,” Engmann says. “I have to remind people that the colonial period in Ghana is when the British were here.” The Danish settlement site dates to the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. During that period, up until the British established their colony, in 1874, the region was under the control of various African powers. Ghana gained its independence in 1957. “Europeans could not build trading fortifications without permission from local warlords and chiefs, to whom they had to pay rent and from whom they sought help when they were in conflict with other European powers,” says Engmann. “When the Dutch, Portuguese, English, Danish, or whomever did not do what local rulers wanted, those rulers could easily stop the flow of trade provisions and valuable commodities such as gold, ivory, and captives coming in.” The Danes purchased the land to build Christiansborg Castle from the paramount chief of the Ga people, Chief Okaikoi, for the sum of 3,200 gold florins.

The Danes faced an unforgiving, dangerous environment. “They were small players facing up against the Dutch and the English in particular,” Engmann says. “When you read historical accounts, various governors are always complaining that they’re being sent the wrong goods to trade, that there aren’t enough men, that there isn’t enough money. Especially in the early days, they’re dropping like flies, they’re dying in large numbers, because they aren’t protected against local diseases, their diet is quite poor, and there’s rampant alcohol consumption.”

Men who established relationships with local women fared better and likely lived much longer than those who did not. “In the beginning, when the Danish first arrived, they had a law against establishing such relationships,” Engmann says. “But, over time, this changed because they realized that those relationships brought certain advantages.” Upon quitting their posts in Africa, some Danish men left their African wives and mixed-race children behind, but others brought their children to Denmark to be educated. According to historian Sandra Greene of Cornell University, local Ga people would have had their own reasons for arranging relationships with Danish men. “Very often marriages weren’t individually decided,” she says. “A political leader who wanted to make an alliance and establish good relationships, even with an individual trader, might marry off a daughter to seal that relationship.”

On occasion, business-minded Ga women sought out relationships with Danish men who could give them access to goods and commodities that they would not have been able to acquire otherwise. Intermarriage could also be a useful tool for the Ga to exert social control. “Europeans in West Africa during [the precolonial] period were not settlers, they were tenants, and those Ga families who decided to give their daughters to these European men were being strategic,” says Ogundiran. “When you have visitors who have certain kinds of power and knowledge that you don’t have, but you want to acquire, intermarriage is an effective way of bridging that gap, and also of domesticating outsiders, keeping a close eye on them.”

Europeans first traded with West Africans directly offshore, from their ships, before building simple trading lodges. As they were made from adobe, these structures are difficult to identify in the archaeological record. Later came the heavily fortified castles that allowed Europeans to establish a permanent commercial presence on the coast. The greatest concentration of these outposts was along the coast of what is now Ghana. Among them was Christiansborg Castle, which, in the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, contained a courtyard, a chapel, a school for educating the children of European men and African women, a warehouse, storerooms, residential quarters, dungeons, and a bell tower. Contemporaneous records show that among the personnel were a governor, a bookkeeper, a physician, a chaplain, a full garrison of Danish and Euro-African soldiers, and enslaved Africans who worked inside the castle, but lived outside.

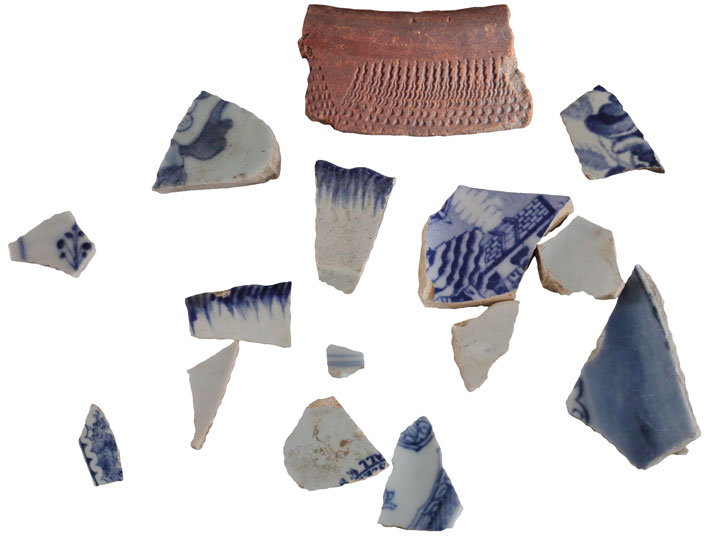

Engmann and her team have discovered that Danish men and their Ga wives established a community that reflected the interconnectedness of the seventeenth- and eighteenth-century mercantile world. “We know that many Danish men traded on their own private accounts,” says Engmann, “including trading captive Africans, to supplement their salary.” She says it’s difficult to establish through the archaeological record alone which objects were used by the Danes, Africans, or Euro-Africans in particular because everybody used objects made both locally and abroad. “They had European-made wardrobes, they had writing desks, pots, pans, Chinese porcelain, and Danish ceramics and pipes,” Engmann says. “But we can’t say it was just Danes that used them.”

The team has uncovered the foundations of several houses that were part of the settlement, including those of what is thought to be a kitchen containing charcoal and three stones for balancing a cooking pot. They’ve also discovered what are commonly called African trade beads, which were manufactured in Italy and Holland, and cowrie shells used as currency. A large assemblage of ceramics found at the site includes Chinese porcelain, as well as English, Dutch, and local pottery. The team has uncovered an abundance of Dutch, German, English, and Danish pipe bowl and stem fragments, as well as some local African smoking pipes, evidence that tobacco was widely consumed at the castle. These artifacts speak to the importance of trade in imported tobacco, particularly from Brazil, in the area at the time.

“As soon as the slave trade really took off in the early seventeenth century, the materials from the tropical world coming in—tobacco, rum, aguardiente, and other kinds of alcohol—began to change the landscape of commerce in West Africa,” says Ogundiran. In the late seventeenth and particularly the eighteenth century, a number of groups in the region began to aggressively expand their territory. “At this time, for instance, the Asante Empire expanded northwards and southwards, producing many prisoners of war, many of whom became captives for the slave trade,” Greene says. Europeans did not necessarily incite local political disputes, but they did provide weapons that helped fuel them and then purchased prisoners of war taken during the armed conflicts that ravaged the region. “There was a lot of political turbulence because of the transatlantic slave trade,” says Engmann. “Not to say that everyone was living harmoniously before, because they were not, but a lot of fighting, kidnapping, and abduction was due to a constant European demand for humans.”

Pawning was another way that some Africans and Europeans acquired human beings to trade. People pawned family members, and sometimes themselves, as collateral in order to obtain imported items. Once they had sold the goods, they would pay the brokers and reclaim those who had been pawned or free themselves. The Danes, however, were careful to avoid trading in pawned people because they needed to maintain good relationships with the Ga.

Archaeological evidence for the experience of enslaved people within the castle is spare, often limited to the remains of spaces, such as Christiansborg’s dungeon cells, in which people were kept for days, weeks, or even months before being transferred to slave ships bound for the West Indies. Under the castle, Engmann’s team has identified the entrance to a tunnel leading to Richter House, a nearby residence once owned by a successful Danish-Ga slave trader. The tunnel, Engmann says, was designed so that captive Africans could be transported from the slave trader’s house directly onto ships without giving them an opportunity to escape or drawing unwanted attention from neighbors. Slavery was not just limited to the confines of the fortress itself. “Many of the people who were growing the crops and selling them in the markets were also enslaved,” Greene says. “They just belonged to local people, instead of being sold to Europeans for export.” Captives bound for the Americas faced a rapid transition from political prisoner to enslaved person. “When an individual arrives in the dungeon, they are still a political prisoner, but then that individual goes through the conversion to Atlantic slavery,” says Ogundiran. “In that space, the material component of an individual’s personality, of an individual’s life, is stripped away.”

Engmann’s team is made up of Danish-Ga descendants of people who worked in the castle and lived close by from the seventeenth through the nineteenth centuries. Some of their ancestors may have built the very settlement the team is excavating. The project, Engmann explains, is a collaborative effort, uncommon in that researchers are conducting excavations of one of their own ancestral communities. This allows them not only to learn about their history, it also provides the opportunity to reframe narratives of Christiansborg Castle and the Danish-Ga settlement that were written from a Eurocentric perspective and left out the voices of local people. Within the project, local knowledge is valued, and oral history is given equal weight alongside the written record.

Engmann has a particularly personal connection to Christiansborg Castle. After taking the advice of an aunt, she visited the castle, where she confirmed that she is not the descendant of a Danish missionary, as she had previously been told, but of a man named Carl Gustav Engmann, who was the governor of Christiansborg Castle from 1752 to 1757 and who later worked for the Danish king in slave trading operations. During his time in Ghana, the governor married a woman named Ashiokai Ahinaekwa, the daughter of Chief Ahinaekwa of Osu, from whom Engmann is also descended. “My experience is much like many other experiences of Danish-Ga people,” Engmann says. “We know we have this heritage and ancestry, and we know we have our surnames, but we don’t often talk about it publicly.”

Plans are in place to develop Christiansborg Castle into a museum where Engmann hopes that artifacts uncovered during the excavations can be displayed and community members can continue to learn about their past. Team member and Danish-Ga descendant Godfred Wulff-Cochrane echoes this sentiment. “There is also a saying,” he says, “that if you don’t know your past, you don’t know where you are going. So, for me to know my past, it gives me the assurance that I am going somewhere.”