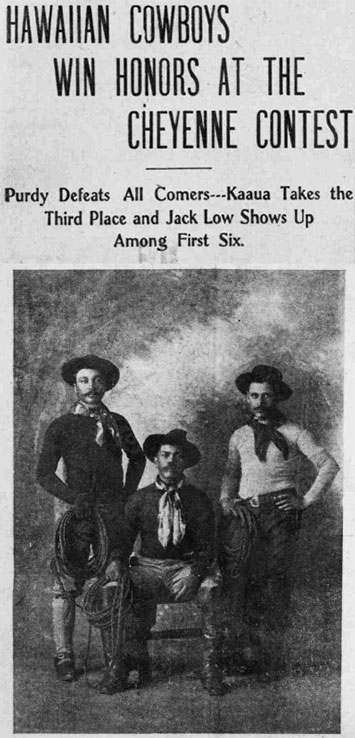

The Frontier Day Rodeo in Cheyenne, Wyoming, in August 1908, brought together some of the best riding and roping champions from across the Americas, from Alaska to the Argentine Pampas. Among them were three unusually dark-skinned cowboys who, according to a newspaper report, were initially mocked by other competitors. But after two days of steer roping, Ikua Purdy, Archie Ka‘au‘a, and Jack Low finished first, third, and sixth—with Purdy cementing a claim as the champion steer roper of the world.

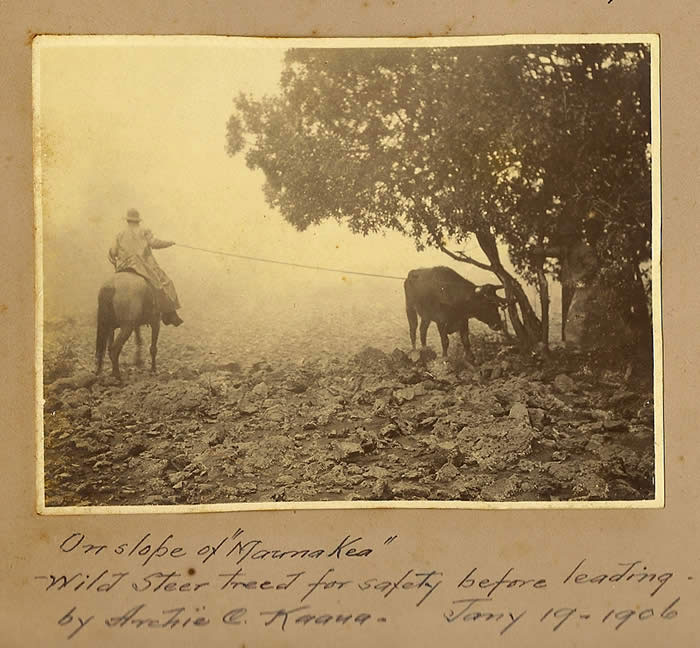

What the other competitors didn’t understand about these cowboys was that they had earned their spurs roping irritable feral cattle on the unpredictable terrain of a dormant volcano: Mauna Kea. The rodeo proved to the mainland what Hawaiians, who greeted the returning heroes with a parade, already knew: that Hawaiian cowboys, called paniolo, are some tough customers.

The Hawaiian monarchy had been overthrown in 1893, and the island chain was annexed by the United States five years later, so the paniolo who beat the mainlanders at their own game became a great source of native pride. They were cowboys, to be sure, but also Hawaiian by blood, culture, and temperament. The paniolo folk tradition evolved over decades, entwining European, Hispanic, and Asian influences with Hawaiian roots. Archaeologists and anthropologists have a term for the creation of a new cultural identity: ethnogenesis. “I think it’s one of the best examples of ethnogenesis,” says Peter Mills, an archaeologist at the University of Hawaii at Hilo, who has studied the history and archaeology of ranching on Mauna Kea for more than a decade. By surveying and excavating ranching stations on the volcano’s slopes, Mills and his colleagues have added a new layer of understanding to the oral history, journals, and ledgers that document the ethnogenesis and life of the paniolo.

You don’t have neck problems, do you?” says Mills as he guides a 4x4 along the first of a series of increasingly harrowing dirt tracks through the ranchlands of Mauna Kea, on the Big Island. After a stop at the palatial headquarters of Parker Ranch—one of the United States’ largest and oldest—for permission to enter its holdings, Mills guides the truck along the lower north slope. The destination is the Humu‘ula district, around 250,000 acres halfway up the mountain’s eastern flank. Humu‘ula has been an important site for Hawaiian ranching since it began in the mid-nineteenth century, and is home to all the ranching stations Mills has studied.

After a few minutes, the clouds part and a crown of white spheres appears briefly on the volcano’s peak, collectively the world’s largest astronomical observatory, nearly 14,000 feet above sea level. Native groups are opposing the construction of another, the massive, sophisticated Thirty Meter Telescope, because Mauna Kea is considered by native Hawaiians to be the islands’ most sacred place. Hawaii’s tallest peak has a long history of visitors from across the ocean, and the earliest of these international migrants—cattle—completely reshaped its landscape.

The first cattle arrived in 1793, when British naval officer George Vancouver made a gift of cows and sheep to King Kamehameha I, with the idea that they might help provision ships. The king accepted the gift—he even ferried some of the cattle ashore in his own canoe—and placed a 10-year kapu, or customary restriction, on hunting them. The cattle thrived and sometimes ran roughshod through villages. The king eventually allowed limited hunting, and not long after his death in 1819, the monarchy began to pay foreigners called “bullock hunters” to track, trap, and shoot feral cattle for the trade in hides, tallow, and salt beef. These men didn’t ride horses or throw lariats at first, but they were the source of Hawaiian cowboy culture.

Mills pulls up next to a field piled with thick, pillowy kikuyu grass, native to Africa and one of the state’s most important pasture grasses. After sliding carefully between strands of barbed wire and high-stepping through knee-deep pasture, Mills arrives at the remains of a stone house that wouldn’t look out of place in County Galway. It was the home of Irishman Jack Purdy, who arrived in Hawaii in the 1820s or 1830s and hunted cattle for the monarchy. He built a house in a markedly Western style, with stone walls, coral lime mortar, and a roof of imported slate at a time when local accommodations were thatch. “I see Ireland when I look at the architecture,” says Mills, “but when I look at the lifestyle, I see something completely different.” Purdy twice married Hawaiian women and started the kind of mixed family that would form the foundation of paniolo culture, which would include his grandson, rodeo champion Ikua Purdy. Mills and archaeologist Adam Johnson of the National Park Service recently used lidar to scan the standing remains, which include the house, stone corral, family graveyard, giant cistern, and more. “Nothing else has been done with this site at all,” says Mills, who hopes to organize a field school, with the permission of the Purdy family and Parker Ranch, to study it in more detail.

Back in the truck, Mills pushes on through clouds, a series of gated fences, and laconic herds of burly cattle, perhaps descendants of Kamehameha’s, to the Humu‘ula area. His paniolo project, co-led by Carolyn White of the University of Nevada, Reno, begins up here, between 4,000 and 7,000 feet above sea level. Since 2001, the project has surveyed 15 sites and dug eight of them. “Plenty of people who grow up here never see this landscape,” Mills says. It’s easy to see why the cattle like it. It’s cool and lush and there are no swarms of gnats or mosquitoes. “There are a lot of things people hate about the outdoors that they don’t have at 6,000 feet.”

The sun comes back out and the trail becomes more precarious and less traveled. The next stop is Lahohinu (literally, “Greasy Scrotum”), the site of the homestead of another early bullock hunter, Englishman Ned Gurney. Like Purdy, Gurney married two Hawaiian women, but, unlike Purdy, he married both at the same time and built his home in the local style. It has since disappeared under the kikuyu. (Gurney also had a memorable run-in with David Douglas, the Scottish botanist of fir fame who, after having breakfast with Gurney, died when he fell into a bullock trap—occupied at the time). Lahohinu also has a site from the next phase in paniolo history. A massive, sprawling koa tree grows out of the stone foundation of a building that was used as a commercial ranching station in the 1870s.

Around 1830, more and better horses arrived, and native governor of the island Kuakini improved the roads. Business connections with the mainland made the hide and tallow trades increasingly profitable. The monarchy invited experienced Hispanic cowboys from the Mexican territory of Alta California, men with names such as Joaquin Armas, Miguel Castro, and Frederico Ramon Baesa, to round up cattle more effectively. These cowboys, or vaqueros, figure prominently in the history of ranching across North America. Unlike the bullock hunters, they came on horseback and didn’t shoot cattle; the blasts scared off other cows and bullet holes decreased the value of hides. The vaqueros lassoed ’em, hamstrung ’em, and finished the job later. If the first bullock hunters provided the genealogical roots of many paniolo, their skills and style came from vaqueros.

Over time many of the Hispanic cowboys returned to the mainland, leaving the ranching work to native Hawaiians and immigrants from Europe and Australia. This community inherited from the vaqueros braided lariats, adorned saddles, bright ponchos, long spurs, bandanas, and floppy wide-brimmed hats. The island cowboys even took their name from Spanish. “I just love that ‘paniolo,’ which means ‘Español’ or ‘Spaniard,’ can come to mean ‘Hawaiian,’” says Mills. But they also maintained and adapted Hawaiian traditions, and incorporated cultural influences from around the world. One can imagine the paniolo working in uncomfortable, isolated places, sharing danger, camaraderie, and ideas—all adding up to “a new version of what being a cowboy is,” says Ben Barna, who worked on a paniolo site for his Ph.D. at the University of Nevada, Reno.

The transition from the monarchy to Western-style land ownership in 1848 opened the way to the construction of more traditional ranches and lowland plantations. By the 1850s, there were 12,000 wild cattle and 8,000 tame cattle on the mountain, fetching between $1.00 and $1.25 a hide. The Gold Rush, the whaling industry, and new plantation laborers made beef a more important and valuable commodity. In Humu‘ula, organized industry took the form of the Waimea Grazing and Agricultural Company (WGAC), which leased the land in 1861.

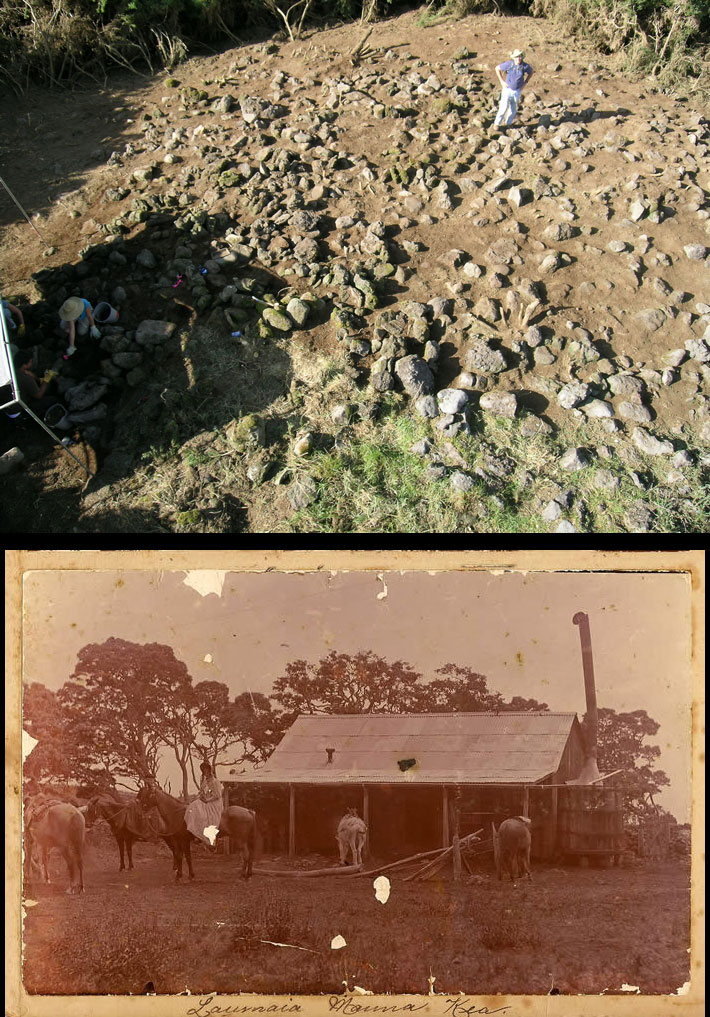

WGAC established ranching stations, including the one at Lahohinu. Mills has excavated part of the site and found records of its construction in an 1868–1869 WGAC ledger, a detailed resource on company operations. It was only used for a brief period, resulting in a modest archaeological assemblage. “The paniolo sites reflect the transience of the population,” says White. “The sites are small and have diverse material culture, but they contain evidence of short-term, even ephemeral, occupation.” For all the official documentation and oral history, archaeology is probably the only source on how day-to-day paniolo culture emerged and developed. The next station along the road is the largest and richest WGAC site, Keanakolu, or “Three Caves.” It is named for a cluster of lava-tube caves nearby that likely provided shelter well before the cattle arrived, when the mountain was roamed by bird-catchers collecting feathers for Hawaii’s dramatic royal cloaks. In a gentle depression are the remains of a stone cabin next to a sprawling landscape of black lava corrals, including the remains of an “80-fathom” perimeter wall built by a Hawaiian laborer in 1868 and documented in the WGAC ledger. Mills and his team surveyed the site in 2003 and excavated the cabin in 2005. “This is one of the richest, densest sites for household items,” says Mills.

In the cabin were patent medicine bottles, such as Perry Davis’ Painkiller and Brown’s Pain Destroyer, usually containing opiates, which suggest physical hardships, self-medication, and even addiction. Percussion caps from rifles dispel the idea that paniolo never used guns, though they may have been used to keep wild dogs at bay. The ammunition also contained fulminate of mercury, certainly a health risk when combusted more or less directly in someone’s face when they were firing a rifle. None of these items are unusual for a ranching site, on the mainland or anywhere, but there are also distinctively Hawaiian artifacts, such as fish bones and seed casings from kukui nuts, both of which must have been brought up from the lowlands and don’t appear in the company ledger. In the lowlands, the oily kukui nuts were burned for light, but the ranching stations were provisioned with kerosene. Mills theorizes that the nuts were used to waterproof leather jackets, chaps, and boots.

There are also artifacts that present mysteries, such as two late nineteenth-century bottles, each with a hole carefully drilled in it. They might have been used as smoking pipes or to measure gunpowder. The cabin itself would have been occupied by a luna, or overseer, and it contained some surprisingly expensive materials, such as a copper embossed lion and a cognac bottle. The pendulum from a wall clock speaks to the commercial nature of the site—after all, time is money.

Finally, Keanakolu also had remains of the Asian influence that arrived on the mountain after the vaqueros left. Immigrant laborers—first from China, then Japan—were brought in to work the lowland plantations. Eventually some were moved seasonally to help with sheep-shearing and other tasks at ranching stations, where they commingled more freely with the paniolo, and where some even made it to horseback. At Keanakolu, the Chinese influence appears in the remains of stoneware food jars imported from Guangdong.

Several hours further along the road, the flora changes dramatically from koa and kikuyu to the uniform, bristly dark green of gorse, a spiny, noxious weed from Scotland, by way of New Zealand, that has consumed large swaths of the volcano. Hidden from view beneath it are the remains of two consecutively occupied ranching stations, separated by a gulch and a decade, and both called Laumai‘a, or “Banana Leaf.” The older one, which the archaeologists dubbed Old Laumai‘a, was used as early as the 1850s and into the 1860s. The later one, Laumai‘a Cabin, was used from about 1880 into the 1950s. “The presence of the two sites so close to each other,” says White, “suggests the flow of people across the landscape and the need for places to stay while on the mountain, as opposed to camping out in the rough.”

Old Laumai‘a was one of the first WGAC stations. After crawling through the gorse to conduct a survey, and returning later with reciprocating saws to clear the area, the archaeologists excavated the site in 2011. They found artifacts typical of a rugged ranch camp, such as pipe fragments, trade beads, burned bone, bottle fragments, and lead waste. But they also found another side of paniolo culture: a thin, delicate, faceted glass ring, buttons with floral designs or faced in jet, a piece of a patterned teapot, and a cologne bottle. “You might be kind of hard-pressed to say there are cowboys up here,” says Barna. According to White, who is interested in expressions of gender in such predominantly male frontier sites, “Masculine fashion does not always reflect our modern sense of masculinity.” There appears to have been a certain sense of style, even flamboyance, among the paniolo, flourishes that came from both vaqueros and Hawaiian culture. The use and appearance of flowers in Hawaii, for example, is not associated with either gender. “But what the hell is that glass ring doing out here?” Mills says. “You start to build a much more complex picture of who was here and what they were doing.”

White is leading the ongoing study of the more recent Laumai‘a Cabin site. In 1876, WGAC had sold the lease to the Humu‘ula Sheep Company, which built the later cabin. One significant change in the period between the two stations was the arrival of Japanese laborers in 1885. In a garbage dump behind the cabin the archaeologists found remnants of tea or sake cups. Barna says they are evidence that the different cultural groups may have been drinking together socially. At several other sites on the mountain are the remains of furo, or Japanese bathhouses built to allow a fire to be lit under a tub. Many Hawaiians today are still familiar with the term.

All these cultural influences accreted in the paniolo: a group of people—mostly men—on a nineteenth-century frontier, with Hawaiian language and values, a Western capitalist economy, Hispanic-American horseback skills and style, and strong Asian influences. It never became a static, mature culture, but was rather, by its nature, in a constant state of becoming, of adding layers of cultural complexity. “You can picture those early cowboys getting together in this communal space and creating this communal culture,” Mills says.

The nature of Hawaiian history and culture were central to making this happen. “The sites underscore the long history of multiethnic interactions in Hawaii and the important roles that Hawaiians played,” says White. The monarchy was strong when colonialists arrived, and Hawaiians were willing and able to adopt outside influences without losing their own identity. The story of the paniolo defies the traditional frontier narrative of “cowboys and Indians,” as well as the traditional colonial narrative of the noble, resistant indigenous society overwhelmed by Western capitalism and exploitation. “The archaeological evidence points to the ways that colonialism and ethnogenesis are organic, and develop in ways that are unpredictable,” says White. Mills and White plan to explore a few more sites and establish a heritage management program, especially as reforestation projects are implemented to control gorse and undo the landscape changes that two centuries of cattle helped cause.

The success of the three paniolo in Wyoming in 1908 secured the place of the paniolo in Hawaiian tradition. Following the overthrow of the monarchy and annexation of Hawaii by the United States in the 1890s, paniolo culture continued to evolve, incorporating more influences from mainland cowboys. Eben Parker Low, one of the great nineteenth-century paniolo, who sponsored the Wyoming trip, had English and Germanic surnames, King Kamehameha I’s blood in his veins (on his mother’s side), and drove cattle at Laumai‘a using vaquero techniques and style. He was known as “Rawhide Ben.” He grew up on the Parker Ranch, and eventually owned a ranch of his own. He met Teddy Roosevelt at the White House. In 1892 he badly injured his hand in a roping accident, and walked six miles to Hopuwai Camp, where the first doctor to attend to him was a Japanese plantation physician.

“I cannot compare the cowboys of this age to what they were fifty or sixty years ago,” he wrote in 1941. “Time has changed the environment and the life of everything and it is difficult to write these lines and believe that I am stating the exact and unadulterated facts. The difference to me is like cheese and chalk to compare the past to the present.”