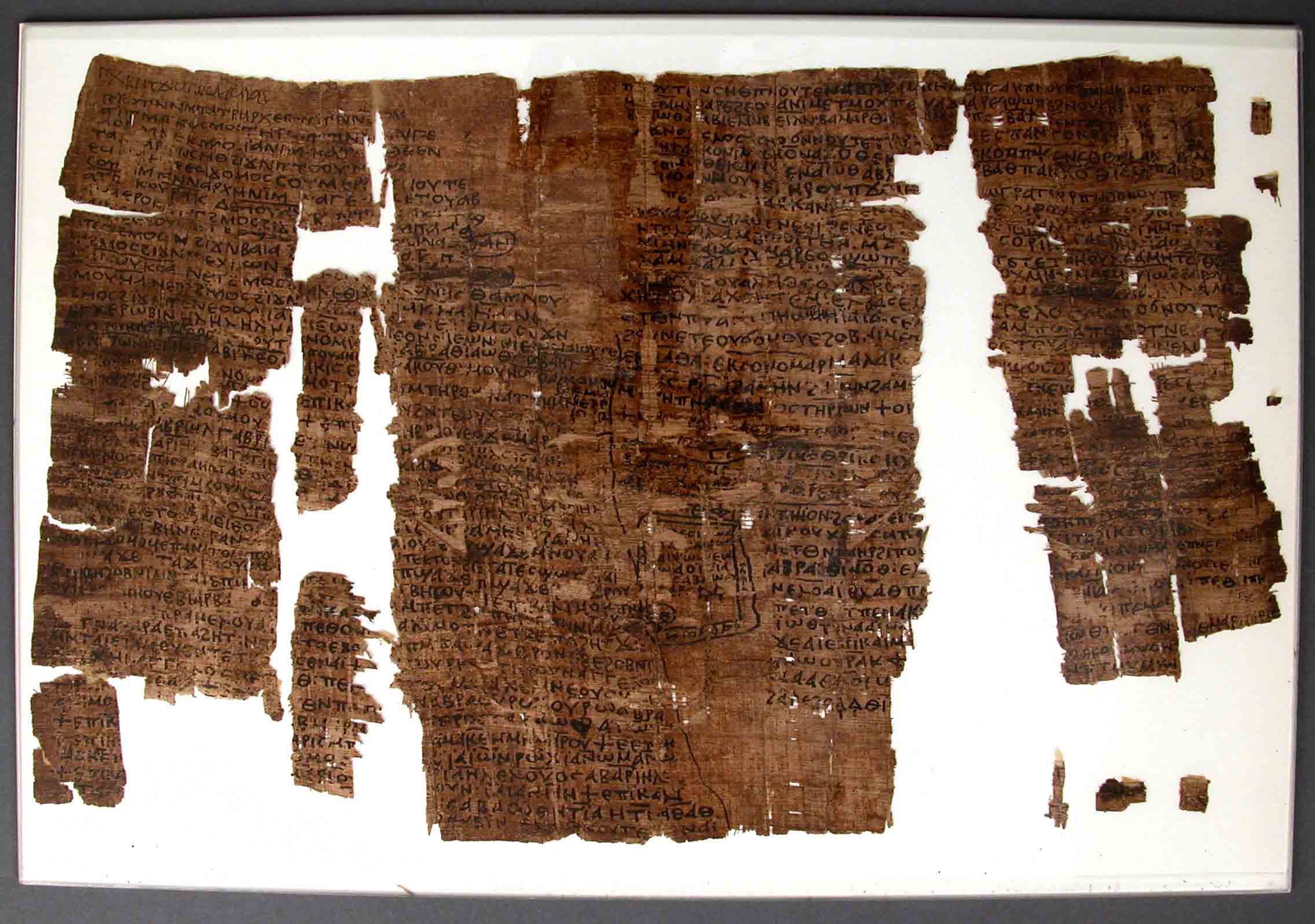

Since at least the twelfth century, indigenous Taino people living on Mona, a small island west of Puerto Rico, ventured deep into its vast network of caves and left images of cemies, or deities, on the chambers’ soft limestone walls. Now a team led by Alice Samson of the University of Leicester and British Museum archaeologist Jago Cooper has found that one of the caves also contains markings left by sixteenth-century Spaniards. “The entrance to this cave is quite difficult to find,” says Cooper. “So the Europeans were probably, at least initially, led there by Taino.” The team has recorded more than 30 historic inscriptions, including crosses, Latin phrases from the Bible, and even the signatures of individuals, such as a sixteenth-century royal official named Francisco Alegre, who had jurisdiction over Mona at one time.

Cooper says that while the European inscriptions were placed close to the indigenous markings, they don’t overlap, leaving the impression that the Spaniards were careful not to deface the Taino rock art. “It’s as if the two traditions were in dialogue with one another,” says Cooper, noting that it is also possible that Taino who had converted to Christianity made some of the crosses. “This is tangible evidence of how people, both European and indigenous, were forging new identities in the Americas. The cave embodies the personal experience of contact between these two cultures.”