According to the Roman historian Suetonius, Augustus boasted that he had found Rome a city of mudbrick and left it a city of marble: “Marmoream se relinquere, quam latericiam accepisset,” in his words. It has become one of the first emperor’s better known quotes, and has seemingly been corroborated by historical and archaeological evidence. The Forum of Augustus, the Temple of Apollo Palatinus, the Theater of Marcellus, the Baths of Agrippa, and the Ara Pacis are just some of the religious buildings, monuments, and infrastructure that were completed under his reign. But just how accurate was his declaration that he transformed Rome into a city of marble? A recent project led by Diane Favro, of the Department of Architecture and Urban Design at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), has reinvestigated the topography of Augustan Rome using digital technology. “As an architectural historian, I wanted to examine the literal impact of Augustan interventions on Rome’s ancient residents,” she says. The results are surprising—Rome may not have been as visibly clad in marble as Augustus claimed.

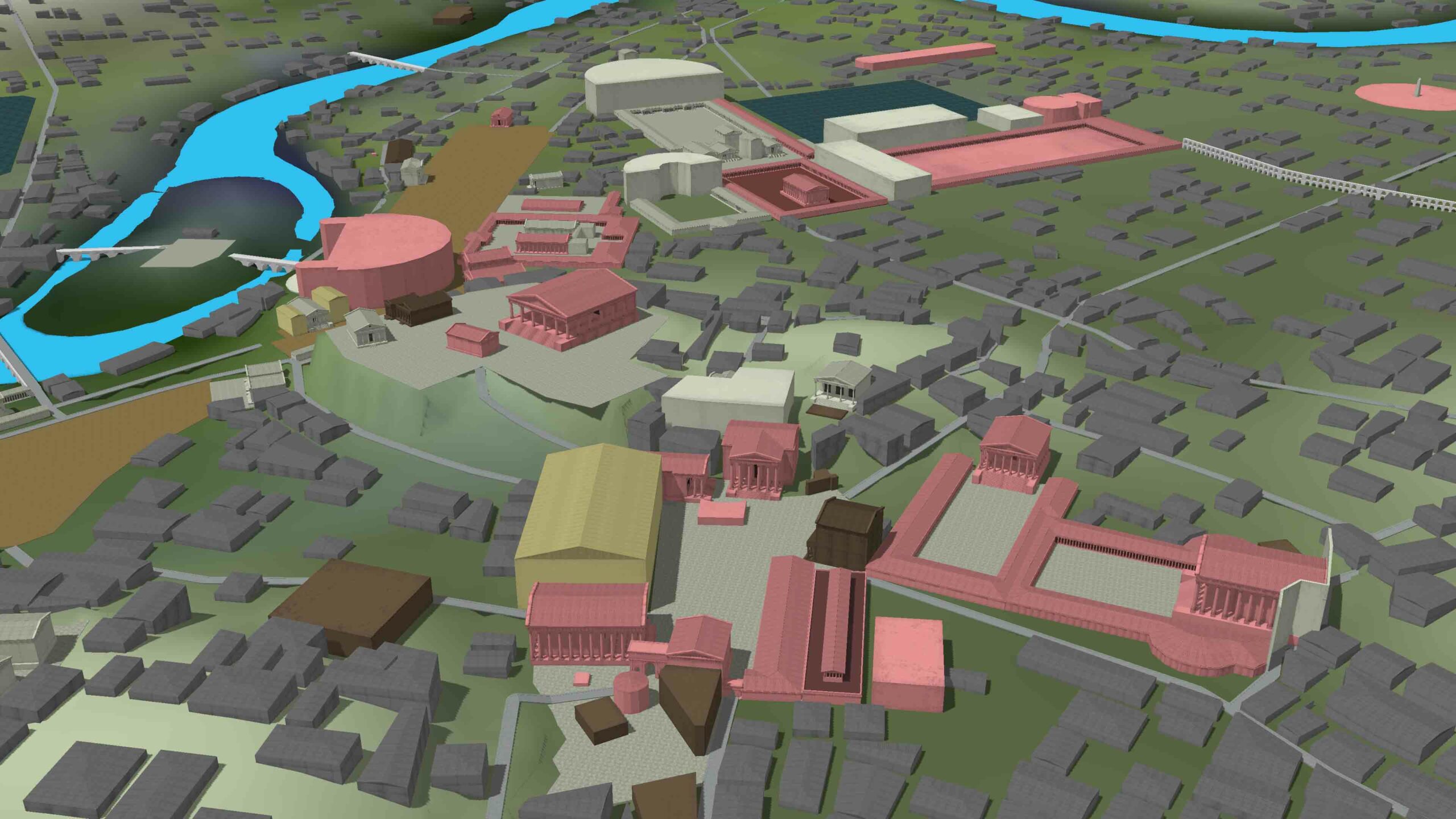

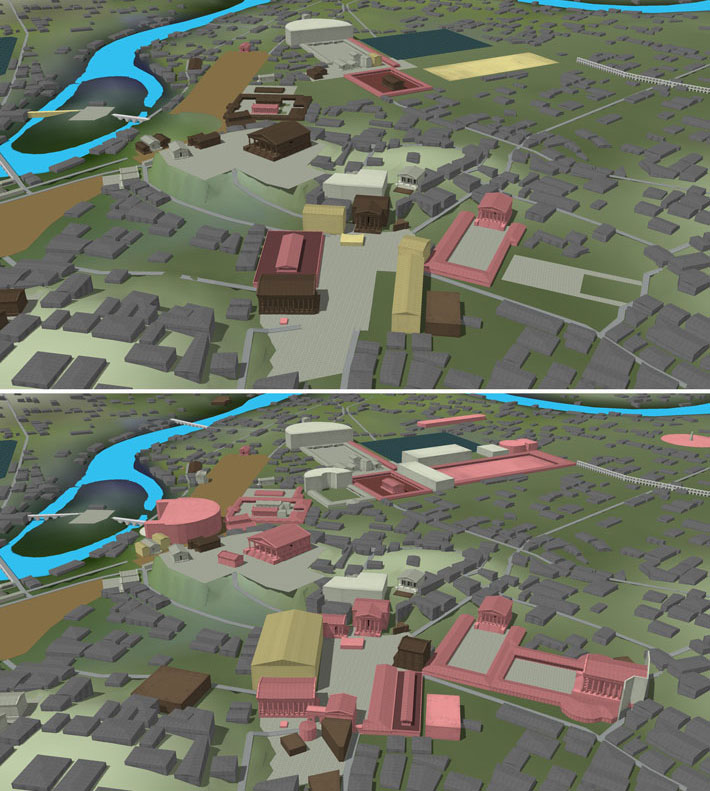

Favro and her team from UCLA’s Experimental Technology Center re-created Rome using procedural modeling, a rule-based technique commonly employed by contemporary urban designers. Relying on archaeological, literary, and historical data, the project researchers created a dynamic database of architectural information that includes the construction dates, measurements, materials, and locations of 400 known Augustan-era buildings. They then added the hypothetical designs and distribution of more than 9,000 additional infill structures, such as houses and shops. The result is a 3-D, Google Earth–type map and model that also demonstrates changes over time. Marble buildings are depicted in red, brick buildings in brown, and buildings under construction in yellow. Users can also view how Rome changed between Augustus’ rise to power in 44 B.C. and his death in A.D. 14. The interactive experience allows users to view Augustan Rome from a variety of perspectives, from street level to high above, from the pyramid of Cestius to the Mausoleum of Augustus. A click of the mouse over an individual building reveals associated information and underlying metadata. It is even possible to assess how light and the angle of the sun affected Rome’s appearance at different times of day.

The digital model has led Favro to conclude that the marble structures of Augustus’ building program actually had little visual impact for Romans walking the streets of the ancient city. The hilly terrain and density of Rome’s urban topography interfered with sight lines and made many of Augustus’ new marble structures difficult to see. Rather, the sights and sounds of incessant construction, as opposed to the completed buildings themselves, may have given the illusion of a newly marble-clad city. “Marble blocks piled high at the city’s edges, showy processions of large building blocks, and the noise and dust raised by the continuous working of hard marble stones at building sites compelled urban residents to believe a pan-urban material transformation was, indeed, under way,” says Favro.

Some scholars have argued that Augustus’ statement was meant to be more metaphorical than literal, and refers to his political transformation of Rome and the foundation of the empire. But there is no doubt that he consciously initiated a building campaign to celebrate Rome’s rebirth. This new digital model provides a cutting-edge way to see, through the eyes of the average Roman citizen, the changing cityscape over which Augustus presided.