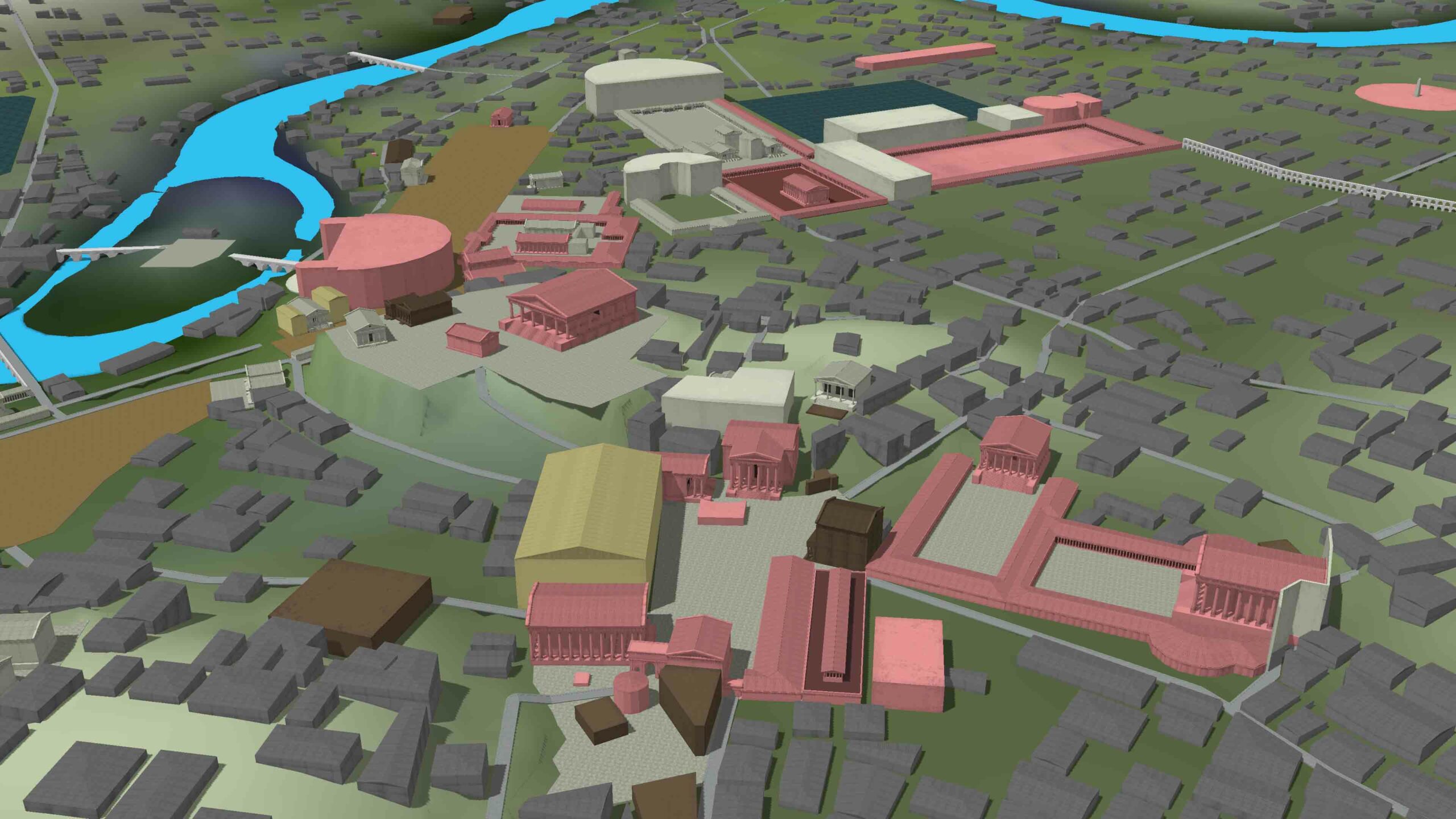

Can an acellular slime mold mimic the Roman road network in the Balkans? It’s not a riddle, but the subject of a new study by researchers in Greece and the United Kingdom.

That slime mold, called Physarum polycephalum, consists of a single large membrane around many cell nuclei, and has drawn the attention of a wide range of scientists because of its uncanny ability to solve almost impossibly complex computational problems.

Through rhythmic contractions of its membrane, called shuttle streaming, the slime mold grows out in search of food. If you put a P. polycephalum into a maze with two food sources in it, over a few days the organism will grow toward the food sources and retract from everywhere else except the shortest path between them. Mathematicians and network analysts call this the “shortest path problem.” When presented with additional food sources, the slime mold forms ever more complex and efficient networks. These “Physarum machines,” as they are known, may help in the understanding of communication, road, and transport networks, which also, over time, come to balance complexity and efficiency.

The new study applied the power of a Physarum machine (and a computer program that simulates its behavior) to landscape-scale archaeology, specifically Roman roads in the Balkans. Researchers placed a P. polycephalum in a petri dish containing 17 little bits of food representing 17 urban centers in the Balkans from the Roman imperial period. The slime mold “imitated rather spectacularly the two main military roads of the area, the Via Egnatia [across Macedonia] and the Via Diagonalis [from central Europe to Constantinople],” says archaeologist Vasilis Evangelidis of the Hellenic Ministry of Education. This was a test case, but future experiments with P. polycephalum might reveal previously unobserved patterns in complex networks of human settlement, trade, and migration.