The scene might have been lifted from the pages of a Scandinavian crime novel: Under a steely sky, a half-dozen skeletons emerge from the cold, wet earth. A strip of yellow and blue tape, fluttering in the wind blowing in from the Baltic Sea, holds back curious onlookers. Portable fences, the kind that go up around construction sites, form a protective ring-within-a-ring around the scene. Yellow plastic stakes mark the spots where bodies, some with clear evidence of brutal blows to the head with an ax or other edged weapon, have already been found.

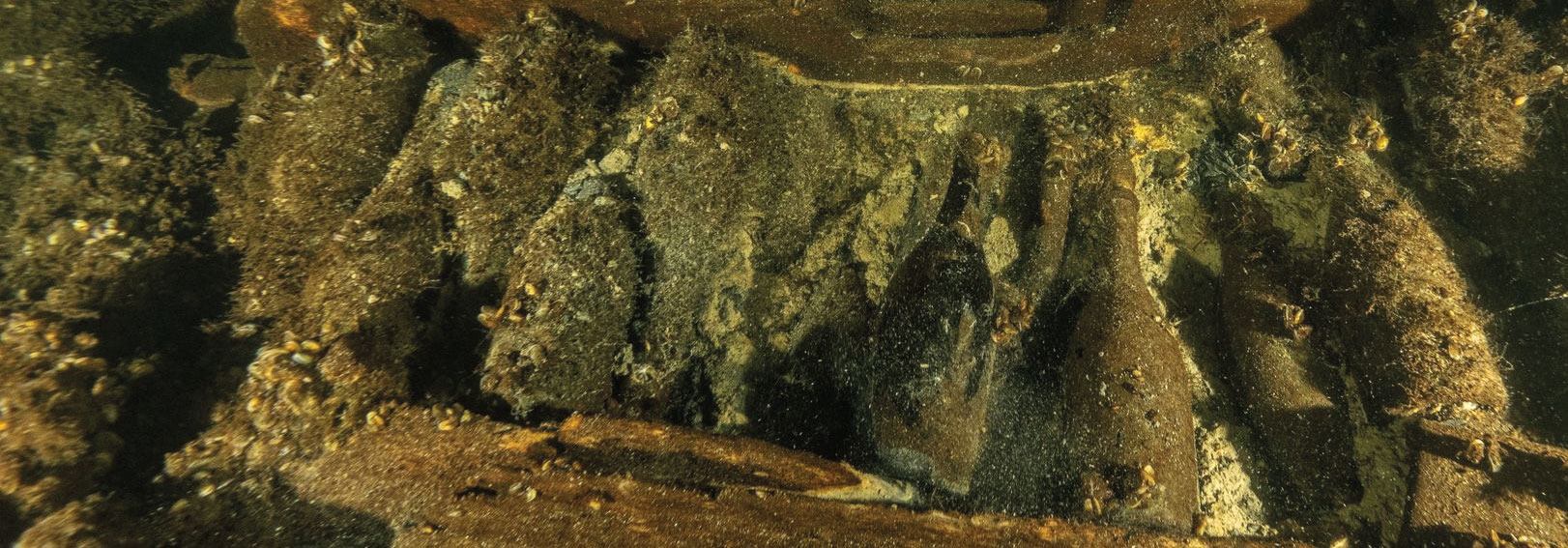

Slowly, trowelful by trowelful, a 12-person team of investigators is excavating the scene of a gruesome mass murder on Öland, an island several miles off the coast of Sweden. In the last five years, they’ve found body after body, sprawled out with many of their bones shattered, on the rough limestone slabs and gravel floor of a 1,500-square-foot house. But it’s a cold case.

The floor is part of a house—the scene of the crime—surrounded by an oval ring of stones and earth, the remains of what was once a wall. Built around A.D. 400, it encircled an area the size of a football field. Now called Sandby Borg, the site is one of more than a dozen similar “borgs,” or forts, on Öland, all built during the Migration Period, a tumultuous era in Europe that began in the fourth century A.D. and hastened the collapse of the Roman Empire. The forts were like safe rooms in case of a siege or surprise attack and could be reached within a few minutes at a dead run from surrounding farms. Sandby Borg’s 15-foot-high ramparts once protected 53 houses and their stores of food. What remains of Sandby Borg’s walls now surround a flat expanse of grass, and aren’t even tall enough to break the strong winds. But 1,500 years ago, Sandby Borg would have been impossible to miss.

Despite its defensive advantages, its end was violent and swift. In a sudden onslaught not long after its construction, its residents were slaughtered, with just enough warning before the attack to hide their valuables. Their bodies were left where they lay, on the floors of their homes and even in smoldering fire pits. The houses were closed up and the place was abandoned. It wasn’t looted after the murders, and neighbors on the densely populated island didn’t interfere with the site, so archaeologists believe that the area was considered taboo for years after the attack. As the turf walls of its houses collapsed, Sandby Borg became a shallow grave, with bones concealed just inches below the surface. It’s unique, says Helena Victor, an archaeologist at the Kalmar County Museum on the mainland just across from the island, because the attack and destruction were so sudden, and the site was never resettled. “This intact moment of an ordinary day is very important, because we know so little about daily life at this time,” she says.

The Sandby Borg project began in 2010 in response to the threat of looting. Researchers at that time had little idea of what they would actually find. Archaeologists testing geophysical prospecting methods in the area noticed that treasure hunters had recently dug pits around the fort, perhaps looking for gold coins. Professional metal detectorists were mobilized to search for anything the looters had missed. They uncovered five different jewelry stashes from houses at the center of the fort. The caches include silver brooches and bells, gold rings, and amber and glass beads. There were even cowrie shell fragments, pierced to be strung on a necklace.

The deposits weren’t randomly placed. Each one was buried just inside the doorway of a house, to the left of the door. Victor, who directs the Sandby Borg excavation, immediately suspected that foul play was behind this arrangement. Her theory was that the women of the fort buried their valuables in predesignated spots. “It’s possible there was an agreement amongst the women—‘if something happens to me, here’s where you’ll find it,’” Victor says. To identify five separate deposits, Victor goes on to explain, is a sign that “something terrible must have happened. These are things you don’t forget or leave behind. Right away we realized they had all died.” Her curiosity piqued, Victor returned to the site in 2011. At that time, she dug three test pits, including one in House 40, a large dwelling in the middle of the fort in which the biggest jewelry stash had been found. On the last day of the weeklong dig, excavators made the grisly discovery of two human feet.

The following year, Victor and her team went back to Sandby Borg and uncovered the rest of the skeleton. It was a man in his late teens, lying on his back. His skull had been split clean open by an ax or sword. To have been hit with that much force in the low-ceilinged houses of the fort, the victim must have been kneeling, his death an execution. Next to him was another young man, lying facedown.

In Sweden, excavations are only funded in case of emergency; for example, if a site is about to be damaged by construction. Because there was no such threat at Sandby Borg, Victor had to scrape together funds for more small digs in the summers of 2013 and 2014. In 2014, they found the partially burned bones of an older man, facedown on top of a hearth. That the body was burned down to the bones in places suggests he was dead when he fell—otherwise he would have moved. “We make these assumptions sometimes,” Victor says. A child’s leg bone was also found not far from the older man, as though more evidence were needed that this had been no ordinary day. “It could have been a grandfather and his grandchild,” Victor says. “It’s a very clear sign someone killed everyone in the fort. Normally, raiders take the children with them [as captives].” The violent deaths deepened the mystery of Sandby Borg—and Victor’s determination to continue digging, at least until House 40 had been fully excavated.

When Sandby Borg was built, Öland must have been a risky and possibly terrifying place to live—it has a seemingly endless coastline for seaborne raiders to land on and no natural barriers to slow down attackers. Even today, the island can be a strange, forbidding place. Twenty times bigger than Manhattan, it is flat, windy, and barren. Yet none of this has stopped people from settling there. The earliest signs of human habitation date back millennia, and the island is still dotted with Bronze Age burial mounds and Viking runestones.

Two thousand years ago, Öland was connected to the mainland by the Baltic, and from there to the Mediterranean via established overland trade routes. Ölanders profited greatly from long-distance trade with the rest of Europe. Archaeological excavations and chance finds have turned up hundreds of Roman coins, bronze statues, glass beads, and vessels dating to the first four centuries A.D., when Öland had extensive contact with the Roman Empire.

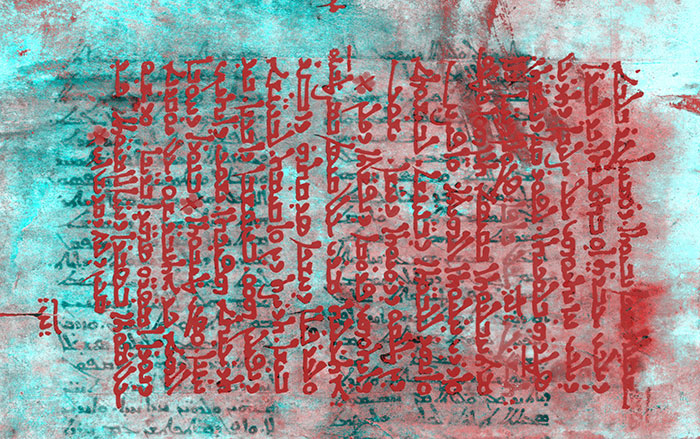

As the empire began to decline, Scandinavian warriors from the islands of Bornholm, Gotland, and Öland found that a set of skills different from what they had sharpened before was now in demand. They had traveled thousands of miles south between A.D. 350 and 500 to work as mercenary bodyguards for the last of the Roman emperors, who paid well to guarantee their loyalty. Ölanders had long brought their wages back to the windswept Baltic island in the form of Roman solidi, gold coins commonly issued in the late empire. The solidi found on the island are distinctive, matching dies that have been uncovered in Rome. “A lot of them are very fresh, in mint condition,” Victor says, without the characteristic wear of coins that have been passed from hand to hand in trade. “There’s a direct link to Rome, and later to Milan and Arles.”

If gold is any measure—and there’s every reason to think it was, considering the tiny holes Öland’s mercenaries drilled in their solidi to check the purity of the gold, and the high concentration of coins found on the island—Sandby Borg was home to some of the island’s most successful warriors. “When we mapped the solidi found on the island, 36 percent were within a mile or so of Sandby Borg,” Victor says.

Then, around A.D. 450, the gold began to run out. The Western Roman Empire was at an end, and there were no emperors left who could pay for imported bodyguards. The latest dated solidi archaeologists have found on the island date to around this time. Archaeological evidence suggests that Öland’s social harmony collapsed along with its economy. Suddenly, the island was full of unemployed soldiers, all of them fingering their swords and eyeing their neighbors’ shining gold and imported glass beads. To protect themselves, people had already begun to build ringforts. In a phenomenon that seems to have been limited to Öland, small farms and hamlets were moved to be closer to the safety of walled borgs that were built to withstand serious assaults. The forts had high earthen walls and gates built using techniques brought home from Rome, with signs of crenellated ramparts and arched gates. The houses were arrayed in a circle along the inner wall and with a central block of houses in the middle. Archaeologists have identified at least 16 borgs on the island, all built at roughly the same time using nearly identical plans.

Much of what archaeologists know about Öland’s ringforts comes from a 1960s dig at Eketorp, a ringfort about 20 miles from Sandby Borg that’s now an open-air museum. As the island’s society crumbled in the Migration Period, many Ölanders abandoned their scattered houses and took up permanent residence behind the tall turf walls of the island’s borgs. Eketorp had been occupied for centuries, from around the same time Sandby Borg was built, to well into the Middle Ages. “After work at Eketorp, the argument was that there wasn’t much more to learn about forts on Öland,” says Ulf Näsman, a Swedish archaeologist who led the Eketorp excavation decades ago and is now a professor at Linnaeus University in Kalmar. “Then came these finds.”

Sandby Borg’s story is, in fact, very different from Eketorp’s. What archaeologists call the “cultural layer” inside the fort, the accumulated trash and debris of daily life, is thin. People lived there for a few months, at most, using it as a shelter rather than a home. “It was obviously built as a refuge and never really occupied,” says Näsman, who is helping excavate House 40’s hearth. That’s a sign that the community that sought protection behind Sandby Borg’s once-mighty walls was an early loser in the unrest that tore the island apart. “When the power struggle started, we think people moved into the fort and brought everything with them,” says Victor. “And then everything stopped. Nothing happened after this massacre.”

Though speculating on how and why the massacre took place is captivating, the event itself is perhaps less important to archaeologists than its suddenness. Because life in the fort was extinguished so abruptly, the site has the potential to illuminate details of daily life in Scandinavia around a.d. 480. The fact that the fort wasn’t looted or burned afterward makes it even more interesting. The killers seem to have left the bodies of their victims where they fell, and then departed, never to return. “It’s compelling because people were killed inside the houses, and then the killers went out, locked the doors, and left,” says Näsman.

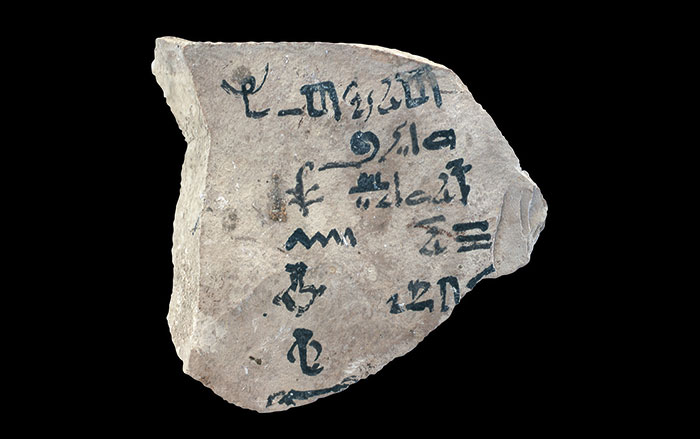

As archaeologists have explored House 40, they’ve uncovered some fascinating details. The team has found lamb bones that place the fort’s final days in the spring. Grains of rye and the earliest mustard seeds yet found in Scandinavia hint at what else might have been on the table. “We’ve even found the skeleton of half a herring, perhaps part of a last meal,” says Victor. “It’s a kind of frozen moment you almost never have.” Clara Alfsdotter, an osteologist at the Bohusläns County Museum in Uddevalla, Sweden, took soil samples from near the stomachs of several skeletons and will send them to a lab in Stockholm. “Hopefully we can see what they consumed before they died,” she says.

For now, though, bodies keep getting in the way. Human remains are complicated and time-consuming to excavate. Part of the reason it’s taken nearly five seasons of digging (albeit only a week or so at a time) to fully explore just one house is that more bodies keep turning up. As clouds and sunshine alternate on a cold June day, Kalmar County Museum archaeologist Frederik Gunnarson squats in the middle of a shallow trench that cuts through the middle of House 40. Bones have been emerging all morning, including what looks like a child’s vertebra, and the team is under pressure. “We’ve got eight people’s bodies here, and six of them are new,” he says. “And we’ve only got two days of digging left. It’s time to make some operational decisions.”

Just two percent of the fort’s interior has been excavated. But the dramatic evidence of slaughter there suggests there may be hundreds more people within the fort’s oval ring wall. “The thing is, this is not the only house,” says Ludvig Papmehl-Dufay, another archaeologist at the Kalmar County Museum. “There must be dead people in the other ones as well. This was quite an attack.”

The most intuitive explanation for such a massacre would be a major battle or siege. At Eketorp, archaeologists found evidence that one of the fort’s gates was badly burned, and the area outside was littered with arrowheads, strong evidence for a failed attack on the fort. But at Sandby Borg, metal detectorists found nothing outside the fort’s walls, likely ruling out a siege or violent assault. And the human remains the team has found thus far are strangely bare—most of the artifacts found were hidden or buried, apparently before the attack. “There is no dress, such as belt buckles [on the skeletons],” Näsman says. “Were they caught unawares at night? Maybe they were nude or in night dress and taken by surprise.”

The assailants didn’t even take the animals. The team has found skeletons of lambs, pigs, and even a horse inside the fort. “Horses are some of the most popular booty, but they left the horse and pigs and lambs behind,” Victor points out. “It’s not normal behavior.” The animals seem to have been locked in and eventually starved to death. Victor argues that the curious abandonment is a sign that the Sandby Borg massacre was perpetrated by someone on the island. “If somebody had attacked from across the sea, residents of Sandby Borg’s neighboring villages would have come and buried them, or at least nicked their sheep,” she says. “There was a struggle on the island, and this is humiliation beyond death. Killing someone is one thing, but forbidding burial is a real demonstration of power.”

As if the gruesome circumstances of the deaths weren’t enough, two of the bodies were found with sheep or goat teeth in their mouths, a nasty twist on the coins typically deposited to smooth a warrior’s way into the afterlife. “It wasn’t enough to kill them and leave them in their houses,” Victor says. “It’s really, really ugly treatment.” Whatever happened at Sandby Borg seems to have left a lasting scar on the island. Villagers in nearby Gårdby remember being told by their parents not to play near the fort’s ruins, and, according to local legend, the town’s churchyard is haunted by ghosts from Sandby Borg.

With help from the Kalmar County Museum, the 2015 excavation was extended a few more days, long enough to fully excavate House 40. The final body count: eight people, including a child between two and six years old. Added to the remains found in neighboring houses, there are 14 known victims of the attack on Sandby Borg. Victor hopes that what she’s found so far, and future research at the fort, will illuminate not just how they died, but also how they lived. Ultimately, that may be a more lasting contribution than the details of the fort’s final hours. After all, “there’s nothing to compare it to,” Victor says. “There’s no ‘normal’ massacre.”