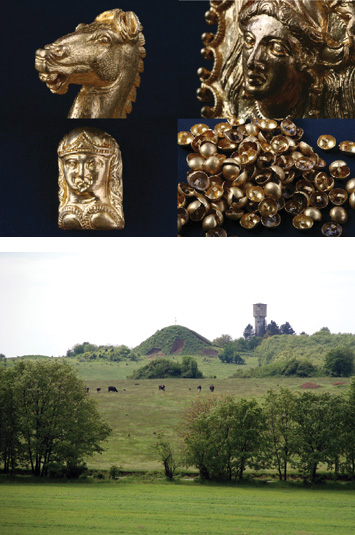

"The Thracians are the most powerful people in the world, except, of course, for the Indians,” wrote the fifth-century B.C. Greek historian Herodotus. In citing the Thracians, he was referring to the group of tribes who inhabited a large part of the Balkans and parts of Western Anatolia—from the Aegean to the Carpathian Mountains, and as far as the Caucasus—from approximately the twelfth century B.C. to the sixth century A.D. Despite their fearsome reputation, relatively little is known about them. Few examples of their writing survive, and what other information we have comes from Greek literary sources and Thracian burial mounds. Many of these mounds have been excavated since the end of the Cold War, when their former lands, Bulgaria and Romania in particular, became accessible to well-trained archaeologists and modern methodology.

This past November, archaeologist Diana Gergova of the National Institute of Archaeology at the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences entered the burial chamber of an almost 60-foot-tall mound in the Sveshtari necropolis, some 250 miles northeast of the Bulgarian capital of Sofia. There she discovered a wooden chest filled with hundreds of gold artifacts. Gergova believes that the burial belonged to a ruler of the Getae, one of the most powerful of the Thracian tribes, who, around 2,400 years ago, were “at their absolute height, politically, culturally, and militarily.”

According to Gergova, the finely crafted gold treasures from Sveshtari help confirm the ancient writers’ accounts of Thracian culture. The craftsmanship also reveals previously unknown stylistic connections to other tribes in the northern and western regions of the Black Sea, providing evidence for a wide cultural ring across Thracian lands. The site could also provide new insight into the Thracian religion, including their belief in the immortal nature of the human soul, which may have influenced early Christianity, says Gergova. “These finds have given us an incredible amount of information about the burial and post-burial practices of the northern Thracians.”