On the outskirts of Fukui, a city of a quarter of a million people in central Japan, a handful of shops and restaurants, a smattering of homes, and a few rice fields line the Ichijo River as it snakes its way through a narrow valley protected on three sides by mountain ranges. Locals as well as tourists enjoy the valley’s scenic beauty, but on the surface there’s nothing particularly noteworthy about the spot. However, a deep history lurks beneath the serene landscape. Few places in Japan are less populated today than they were five centuries ago—but the Ichijo Valley is one of them. It may be difficult to imagine that this was once the location of the lively city of Ichijodani, where events that helped alter the course of Japan’s history took place.

Once a year, in August, festivals attended by thousands transform this placid valley into the thriving metropolis it was from around 1471 to 1573, when the powerful Asakura clan ruled the province of Echizen from Ichijodani, one of medieval Japan’s largest cities. On festival nights, 15,000 lanterns illuminate the dark sky, reflecting what the valley may have looked like 500 years ago, when it was home to as many as 10,000 people. One of the highlights is a procession of men wearing traditional samurai armor and bearing traditional samurai arms in an homage to these elite warriors.

Under the Asakura, Ichijodani grew to rival even the imperial capital of Kyoto, the center of the nation’s art and culture, which had been home to the emperor of Japan and the imperial court since a.d. 794. Though the memory of Ichijodani is kept alive today by the festival honoring its past, there is very little mention of it in history books. History is written by the victors, as they say, and Ichijodani was on the wrong side of history. In 1573, when the city was at its zenith, it was razed by the armies of Oda Nobunaga, one of the most celebrated figures in Japanese history, who helped unify the country and bring to an end a tumultuous century known as the Sengoku or Warring States period (1473–1573).

Obscured under rice fields for 400 years, Ichijodani was only rediscovered by archaeologists in the 1960s. The city was known from medieval letters and court documents, and some Buddhist statues and stone grave markers had remained visible aboveground over the centuries. Nonetheless, archaeologists were stunned by what they encountered beneath the valley floor. The site’s extent and state of preservation were incomparable; Ichijodani was a time capsule preserving a bygone era. After more than 100 excavation campaigns carried out over six decades, some of which continue today, archaeologists can finally resurrect Ichijodani’s past. In the process, they have revealed the most complete picture ever formed of what life was like in a late medieval Japanese samurai city. “Ichijodani is the only site where a wide range of artifacts and archaeological features provide insights into the culture and lives of citizens and lords during the Warring States period,” says Daichi Yamaguchi, curator of archaeology at the Ichijodani Asakura Family Site Museum. “The site’s comprehensiveness has provided us with a wealth of materials to re-create the medieval world.” Ichijodani also offers an in-depth look at the consequences of two samurai armies meeting on the battlefield—only one can claim victory.

Japanese samurai are among the world’s most storied warriors. Known for their disciplined code of conduct, their deadly fighting skills, and their katanas, a type of curved sword, samurai were an integral part of Japanese culture for almost 1,000 years. They originated as lower- to middle-class servants who were hired as mercenaries by aristocrats, but eventually developed into a distinctive warrior class—one that become so powerful that samurai began to overshadow even the emperor himself. Japan’s legendary first emperor, Jimmu, is said to have founded the imperial dynasty in 660 b.c. in the Yamato region of southern and central Japan. For centuries, a series of emperors expanded their territory and rule outward until, by the eighth century a.d., their domain encompassed most of the modern nation. By the twelfth century, the emperor’s influence had waned as the power of the samurai increased. The first samurai shogun, a hereditary title given to Japan’s top military leader, was appointed in 1192. While the emperor remained the official head of Japan’s government, it was the shogun and his army of loyal samurai who actually ruled the country.

During the Warring States period, the shogun’s influence weakened as well, and Japan’s central government in Kyoto collapsed, leaving control of the country in the hands of ambitious regional warlords known as daimyo. The daimyo amassed armies of samurai and frequently fought among themselves in an internecine struggle to attain power and territory. The samurai who lived during this era knew only unceasing battle. At this time of anarchy, civil war, and social upheaval, some warrior families rose up and overthrew their superiors. One of these families was the Asakura.

By 1471, the Asakura, who originally served the leading family of Echizen Province, had ousted their overlords and seized control of the region. They would go on to rule the province for five generations. Persistent warfare throughout the period spurred the rise of what are known as castle towns. Initially, these were defensive fortresses, but they soon grew into administrative centers and military headquarters for the regional daimyo. The Asakura needed a castle town from which to operate and monitor their new territory. Takakage Asakura, the first head of the dynasty, looked to the Ichijo Valley, where his family had owned property for centuries, to build his castle. Although the valley’s off-the-beaten-path location may have made Takakage’s choice an unorthodox one, its natural advantages made it the ideal place to construct his castle town, which became one of the largest such settlements of its era. The valley is around two miles long and only about 260 feet wide at its narrowest point. It could be sealed off to intruders and protected by defensive gates at either end. Watchtowers built atop the 1,400-foot mountains that rise above the settlement would provide sweeping views in all directions and enable the Asakura daimyo to anticipate any signs of incoming danger.

The Asakura chose not to build their fortified castle in the middle of the town, as was the custom, but on a mountaintop high above the city. Even today, the site is difficult to access. Archaeologists are using airborne lidar to survey the steep terrain and locate structures concealed by dense mountain vegetation. “Lidar has proven especially helpful for studying the fortified structures around Ichijodani,” says Yamaguchi. The Asakura castle was a complex of buildings and defensive features including guardhouses, embankments, earthworks, moats, and a network of more than 140 trenches, as well as residences and temples. The castle would have been nearly impossible for an advancing army to assault, and the Asakura daimyo appear to have envisioned it as a final place of refuge—for themselves—during an invasion. It is so high above Ichijodani, however, that it was ineffective in defending the city itself. This would later prove costly.

Like all Warring States daimyo, the Asakura’s true strength lay in their army of vassals and retainers. “The Asakura family implemented an existing system in which samurai warriors became retainers, serving their masters while also handling administrative affairs and legal proceedings under their orders,” says Yamaguchi. After taking power, Takakage ordered his samurai to relocate to Ichijodani from across Echizen Province. It’s difficult to estimate how many of these warriors actually lived in the city, but contemporaneous historical records say that Asakura lords could mobilize as many as 12,000 troops. Scholars are certain, however, that the daimyo’s most trusted and highest-ranking samurai lived close to their leader. Over the past few decades, archaeologists have excavated a number of samurai estates located in Ichijodani. These properties are recognizable by their expansive rectangular plots enclosed by earthen walls with gated entranceways. The compounds often contained living quarters, entertainment spaces, wells, gardens, and outhouses, although not a great deal survives apart from their stone foundations. In excavations of some of these properties, archaeologists are uncovering objects of daily life that are enabling them to reconstruct the lives of the samurai. Among the artifacts they frequently find are parts of swords and pieces of armor, personal items such as combs, hairpins, mirrors, writing implements, and chopsticks. They have also unearthed coins and gaming pieces the samurai used to play the chess-like game shogi, as well as a wide variety of ceramics, including tea paraphernalia used to entertain guests.

Archaeologists have been surprised to learn how prevalent tea culture and elaborate tea ceremonies were in Ichijodani among not only the highest-ranking rulers and lords, but even among lower-ranking samurai and townspeople. “The tea ceremony is emblematic of Japanese culture. It’s very refined, very calm and meditative, and is connected to the history of the samurai in intriguing ways,” says historian Morgan Pitelka of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. “Finding these types of ceramics in Kyoto isn’t surprising, because we know that’s where tea culture developed, but finding them in Ichijodani and other provincial capitals shows that this was becoming a practice spread throughout the whole archipelago.”

Discovering evidence of such high-culture objects in a provincial city such as Ichijodani may not be so out of the ordinary, however, given the circumstances of the era. The Warring States period, and especially the Onin War, a struggle for succession that began in 1467 and lasted for a decade, left much of Kyoto in ruins and forced many of its citizens to flee. Ichijodani was only a three- or four-day journey north of the capital and soon became a haven for crowds of refugee monks, artists, poets, intellectuals, and craftspeople who brought elements of Kyoto’s cosmopolitan culture with them. Ichijodani may have been a wartime city that was built as a result of the era’s martial necessities, but it grew into a diverse and bustling metropolis. During an epoch defined by chaos, Ichijodani seems to have been a model of stability and prosperity.

Since most Japanese cities dating to the medieval period are still occupied, it has often been difficult for archaeologists to access deep layers that might provide clues to what they looked like hundreds of years ago. Yet the circumstances surrounding Ichijodani’s destruction have made it an invaluable source of information about medieval urban life. Thus far, archaeologists have recovered more than 1.7 million artifacts, which, Yamaguchi says, provide exceptional evidence of what type of people lived in each building.

As they investigate the city, archaeologists are learning that the citizens of Ichijodani engaged in a variety of industries. There were metal casters, potters, bead makers, gunsmiths, textile dyers, lacquerers, brewers, and woodworkers. The city even had at least one resident doctor. While excavating a particular property, archaeologists found utensils for mixing and grinding medicines, as well as rare fragments of a thirteenth-century Chinese medical text. Ichijodani’s doctor and other residents would have had access to a wide range of foreign goods via river trade routes that connected the city to the Sea of Japan 20 miles away. Archaeologists have discovered evidence of infrastructure attesting to a thriving community of traders and merchants. In 2017, for example, they unearthed a section of stone pavement that might have been used to access a river port. “Due to the city’s advantageous location,” says Yamaguchi, “there was a vibrant exchange of goods and information in Ichijodani.”

At the heart of Ichijodani sat the Asakura palace, or yakata. This enormous complex was protected on three sides by earthen walls and a moat. Today, a ceremonial gate constructed later, during the Edo period (1603–1868), to honor Yoshikage Asakura, the last Asakura daimyo, still stands at the site. Spread across 87,000 square feet, the yakata matched the size of the one belonging to the shogun in Kyoto, a fact that was unlikely to have been coincidental. “The Asakura were highly influenced by the Kyoto shogunate,” Pitelka says.

While the yakata was the primary residence of the Asakura lord—where he slept and conducted his daily activities—the sprawling complex served many other functions. Archaeologists have uncovered thousands of artifacts that reflect the public and private activities that occurred within its gates. “Excavations at the Asakura yakata have shown that there were different uses of space based on social status,” says Yamaguchi. “There were distinct areas for retainers and the Asakura family.” The complex had guardhouses, stables, parade grounds, kitchens, sleeping quarters, bathhouses, reception halls, and performance spaces. There were also four gardens, including one that contains remnants of the oldest Japanese flowerbed ever excavated.

Formal ceremonies, banquets, and feasts would have been an important part of life in the yakata, and archaeologists have unearthed many artifacts related to these events on the property. These include imported ceramics, especially from China, that must have been among the Asakura clan’s prized possessions and would have been prominently displayed throughout the residence and reserved for special occasions. Some of the more unique objects are small circular boxes called magemono that were made from thin strips of wood and used to serve seafood delicacies.

Archaeologists have also found an entirely different kind of pottery in great quantities throughout the yakata: small, inexpensive, unglazed earthenware dishes called kawarake that were sometimes used as oil lamps. “You very rarely see these objects in museums,” says Pitelka. “They’re not well documented because they’re not really special. Archaeologists are the only people who have ever really paid attention to them.” These unassuming cups played an integral role in the feasts and toasts of high-ranking samurai such as the Asakura.

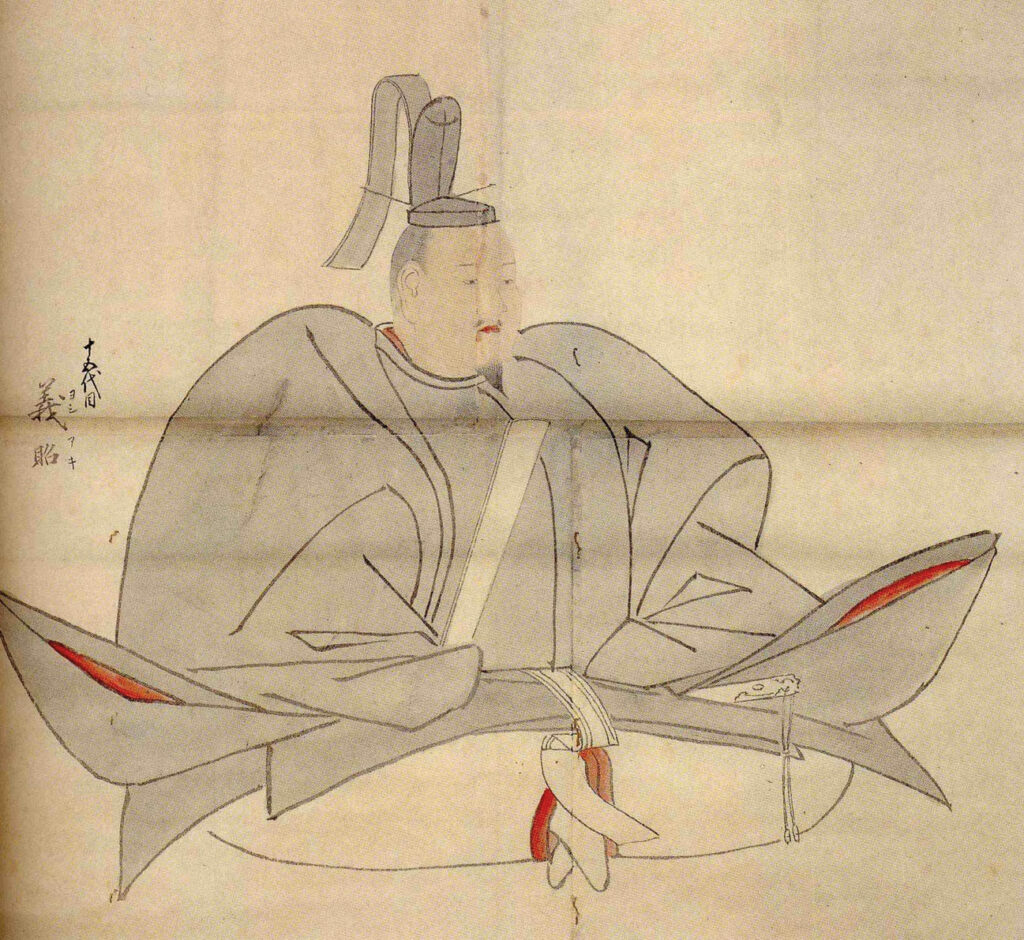

More than a ton of kawarake fragments have been found in the moat surrounding the yakata. Traditionally, these vessels were only used once, then broken and discarded. It was a special honor, and a sign of status and respect, for a host to offer a guest food or a drink in a dish that had never been used before and never would be again. Hundreds, if not thousands, of kawarake may have held food and drink at the most elaborate banquets hosted by the Asakura. “The palace was renowned for its hospitality,” says Yamaguchi. “For Warring States–period daimyo, demonstrating generosity and hospitality was essential to maintaining prestige.” The Asakura household’s generosity would be on full display beginning in 1567. At this time, Yoshikage welcomed his most illustrious guest: Yoshiaki Ashikaga, the heir to the shogunate in Kyoto.

Members of Yoshiaki’s clan, the Ashikaga, had served as shoguns since 1336. However, his family had lost much of its influence during the Warring States period, and in 1565, Yoshiteru Ashikaga, the reigning shogun and Yoshiaki’s brother, was assassinated. This forced the young heir to flee to the provinces. “I think Yoshiaki probably said, ‘Where can I go without exposing myself to the possibility of kidnapping or murder? What’s not too far away, and where do I have people who have shown support for my family in the past?’” says Pitelka. He chose Ichijodani.

For nine months, Yoshiaki lived in a temple compound just outside the city’s southern gate. During his stay, Yoshikage hosted him at various social events, none more important than Yoshiaki’s genpuku, or coming-of-age ceremony, which took place at the yakata. This would have been an ostentatious display attended by as many as 200 guests. Toasts would have been made, food consumed, and gifts such as long swords, suits of armor, and horses exchanged. Hosting the genpuku was a sign that the Asakura clan’s influence was growing. Ichijodani’s future appeared bright. But just five years later, the city was erased from existence.

For reasons that scholars still do not fully understand, a short time after the genpuku, a rift developed between the presumptive shogun and Yoshikage. Having gained momentum during his residence in Ichijodani, Yoshiaki departed the city and planned to return to Kyoto to establish himself as the rightful shogun. He asked Yoshikage to join him on his campaign, but the Asakura lord refused. The young heir turned to another powerful daimyo, Oda Nobunaga, a ruthless military leader who had risen up from his origins in nearby Owari Province and was fast becoming the most powerful warlord in Japan. Nobunaga did, in fact, help restore Yoshiaki as shogun, yet his ambitions knew few limits. Nobunaga’s influence became so great that the new shogun became his puppet. But that wasn’t enough for Nobunaga. “He wants to be the guy in charge,” says Pitelka, “so he starts to emerge as this tyrant.”

Daimyo across Japan, including the Asakura, formed an alliance to counter Nobunaga and his army of supporters. “To put it very bluntly, they chose a side,” says Pitelka, “and they chose wrong.” Nobunaga resolved to eliminate the Asakura and their allies. After a series of clashes over three years, his forces inflicted a decisive blow against Yoshikage in 1573 at the Battle of Tonezaka, around 30 miles from Ichijodani. With his army scattered, Yoshikage fled to his capital city, but remained there only a day before retreating farther inland.

Nobunaga pursued Yoshikage’s trail to Ichijodani, not knowing that he was already gone. At this point, the city would have had few defenders, and Nobunaga showed little restraint. On August 18, 1573, his forces torched the city. “Archaeological evidence of fire has been discovered everywhere,” Yamaguchi says. “During excavations of the yakata, layers of burned soil were found directly above each archaeological feature, and foundation stones and paving stones were all visibly burned red.” The people trapped in the city must have panicked and many of them perished. “It was just a bloodbath,” says Pitelka. Contemporaneous sources say that the fire burned for three days, after which there was nothing and nobody left––no houses, no shops, no townspeople, no samurai. Over the ensuing centuries, the Ichijo Valley reverted to a sleepy and idyllic landscape. Ichijodani was buried and largely forgotten.

Shattered and betrayed by those close to him, Yoshikage committed seppuku, or ritual suicide, essentially ending the long-distinguished line of Asakura samurai. “There were many moments in the years leading up to their destruction when things could have gone the other way for the Asakura,” says Pitelka. “If one major battle had gone against Nobunaga, they would have been betting on the right horse—and the entire history of Japan would have been different.” Instead, Ichijodani was fated to become a footnote in the annals of history, a casualty of the march toward Japanese unification. Nobunaga ultimately deposed Yoshiaki as shogun and forced him into exile, ending the Ashikaga shogunate’s 237-year rule.

Nobunaga and his two successors, Hideyoshi Toyotomi and Ieyasu Tokugawa, brought to a close more than a century of unrelenting war by conquering and unifying Japan. In 1603, Tokugawa reestablished the shogunate, which his heirs would control for next 265 years, until the late nineteenth century, when the modern Japanese government abolished the title of shogun and the entire samurai class. So ended the Age of the Samurai.