In many ways, the story of the Erechtheion is the story of Athens. “The Erechtheion was a means to encompass, within its footprint, relics of early Athenian myth and religion,” says classical art historian Jeffrey Hurwit. It was there that the memory of the dispute between Athena and Poseidon over the patronage of the city was preserved in what the Athenians regarded as the impression of the god’s trident, visible through a hole left in the floor of the north porch. That foundational legend was also preserved in the tales of a sea he caused to well up during the contest, long believed to be under the building, and in the olive tree that Athena caused to sprout on this spot and that marked her victory. And in this location was kept the olivewood statue of Athena Polias (Athena of the City), the Athenians’ most sacred relic, an object so ancient that not even they knew where it had come from.

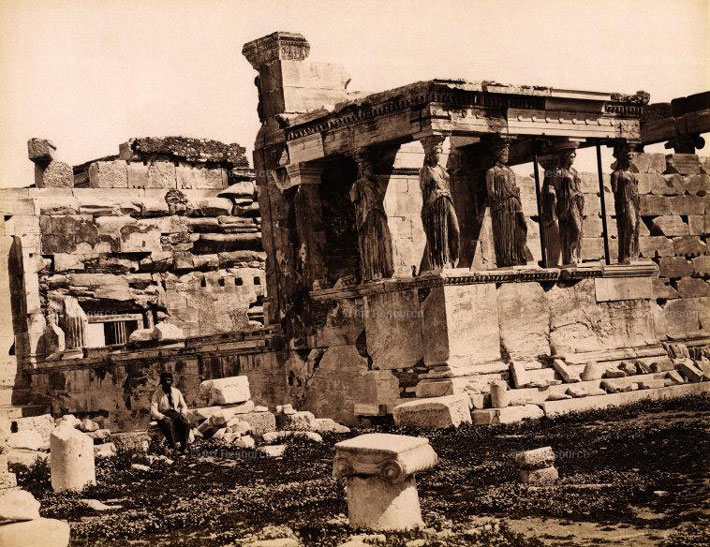

Since its construction on the Acropolis’ north side between 421 and 406 B.C., when it replaced an earlier temple to Athena, the Erechtheion—named after Erechtheus, king of Athens and foster son of Athena—has had a complicated history of use, reuse, destruction, and renovation that mirrors the history of the city. In the fifth century B.C., the unique, asymmetrical structure—its highly unusual shape largely determined by the irregular terrain—served not only as a temple to both Athena and Poseidon, but also as home to the cults of the god Hephaistos, Erechtheus, and the hero Boutes, Erechtheus’ brother. The building underwent its first major repairs after it was burned during the Roman general Sulla’s siege of Athens in the first century B.C. Since then the Erechtheion has been a church (in the early Byzantine period), a palace for the bishop (during the Frankish period), and a dwelling for the harem of the Turkish garrison commander (in the Ottoman period). Between 1801 and 1812, sculptures, including one of the six caryatids that held up the south porch, were removed to England by Lord Elgin, and during the Greek War of Independence, the ceiling of the north porch was blown up.

The Erechtheion was the first building that Nikolaos Balanos addressed during his Acropolis restoration project, and thus the first place where he employed the techniques that were to prove so disastrous—the use of corrosive iron to reinforce fragile architectural members, the cutting and removal of ancient stones, and the haphazard placement of random fragments to fill in and restore missing sections of the ancient buildings. As a result of Balanos’ interventions and the building’s repeated recasting, much about its ancient appearance is lost. But between 1979 and 1987, 23 blocks of the north wall that had been incorrectly used to restore the south wall were replaced in their original positions, and new blocks were made for the south wall. This raised the height of the north wall by four courses, bringing it closer to its original height. Because scholars haven’t yet discovered a way to protect the surface of the marble that makes up the Acropolis’ major monuments, the remaining caryatids that supported the south porch were removed in 1978 and all were replaced with copies. The originals now sit in the Acropolis Museum, where they were recently cleaned using pulse laser ablation, the same technique that was used on the coffered ceiling of the caryatid porch and on the west frieze of the Parthenon. This technique, explains Demetrios Anglos of the Foundation for Research and Technology at the Institute of Electronic Structure and Laser in Crete, who oversaw the efforts, involves directing the laser for a short time in a highly focused way and concentrating it on a small volume of material so the dirt is removed in a nondestructive manner. “We do this to clean the marble,” Anglos explains, “and to reach a place that is acceptable from both a materials and aesthetic point of view.”