While a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Cambridge, Melanie Pitkin became interested in a particular Egyptian limestone stela held by the university’s Fitzwilliam Museum. She had been working with the Fitzwilliam Egyptian Coffins Project, during which time she and her colleagues found that the practice of recycling wood from older coffins to make new ones was much more common in ancient Egypt than previously known. Pitkin was curious as to how the practice of reusing objects translated to other materials. Her Fitzwilliam colleague, Egyptologist Helen Strudwick, encouraged her to investigate the limestone stela, also known as a false door, which had been used for the tomb of a woman named Hemi-Ra during the First Intermediate Period (ca. 2150–2030 B.C.). This was a time of political breakdown and disruption, during which control of Egypt was divided between rival power bases in Herakleopolis in northern Egypt and Thebes in southern Egypt.

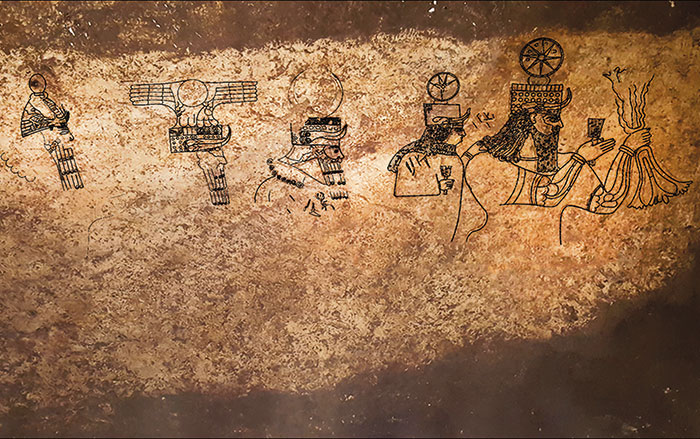

False doors were intended to serve as portals that allowed the ka, or life force, of the deceased to move back and forth between the tomb and the afterlife. “Family members and priests would come to the tomb where the false door was standing and they would recite the name of the deceased and his or her achievements and leave offerings,” says Pitkin, who is now senior curator of antiquities at the University of Sydney’s Chau Chak Wing Museum as well as an affiliated researcher at the Fitzwilliam Museum. “The ka of the deceased would then magically travel between the burial chamber and the netherworld. It would come and collect the food, drink, and offerings from the tomb to help sustain it in the afterlife.”

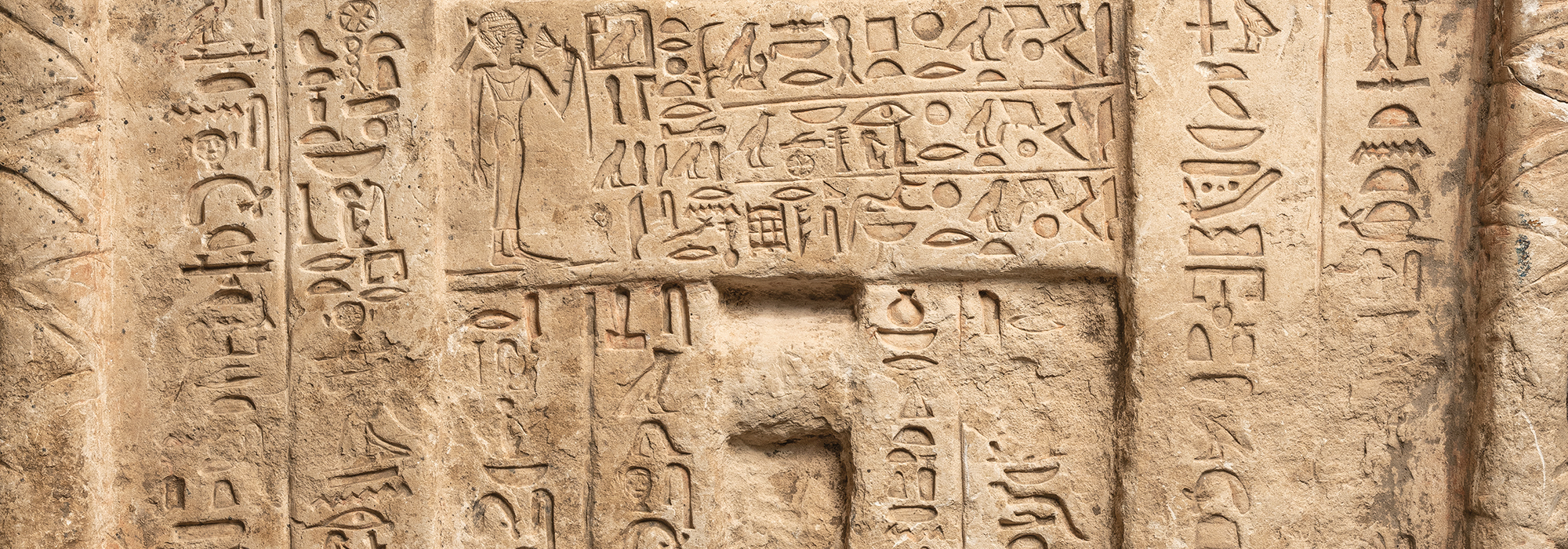

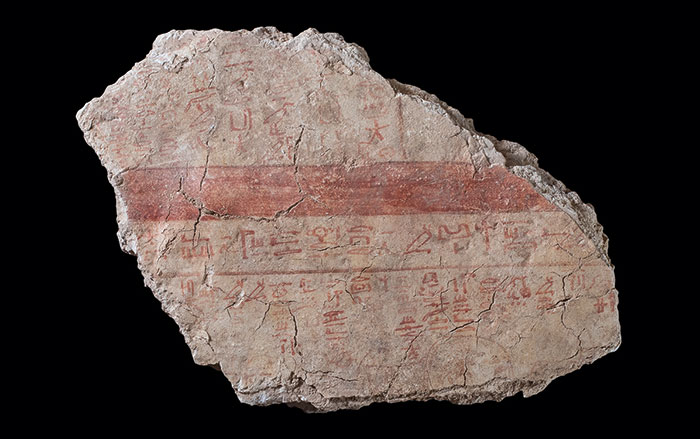

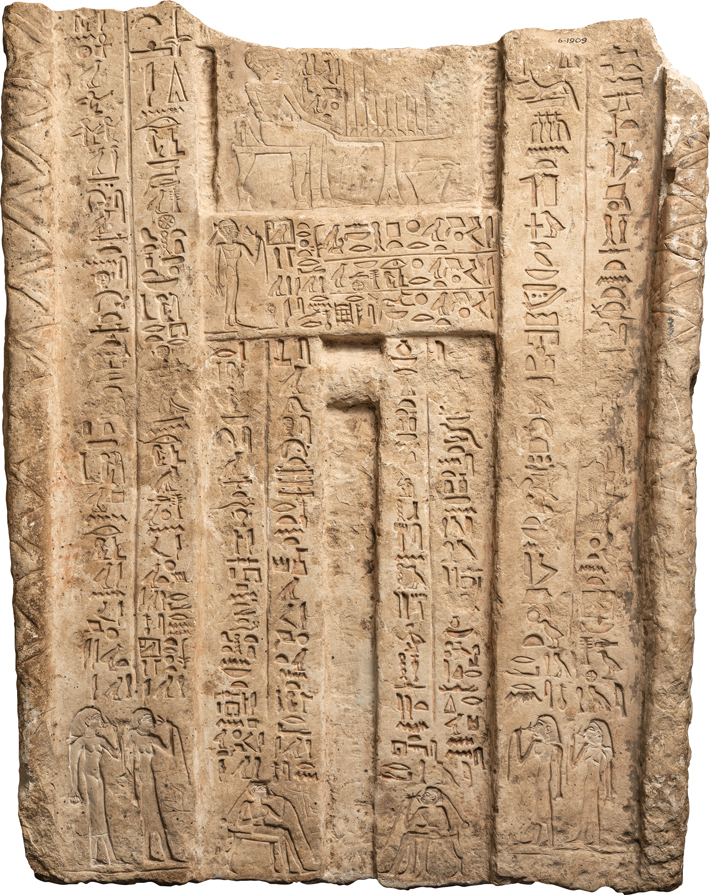

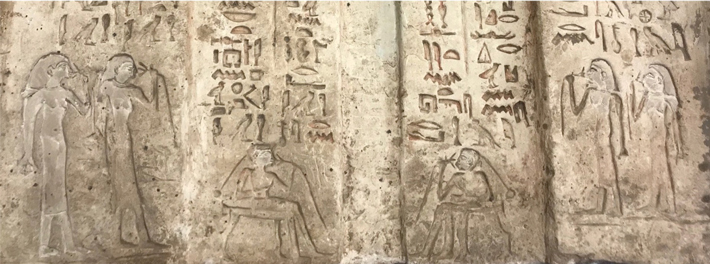

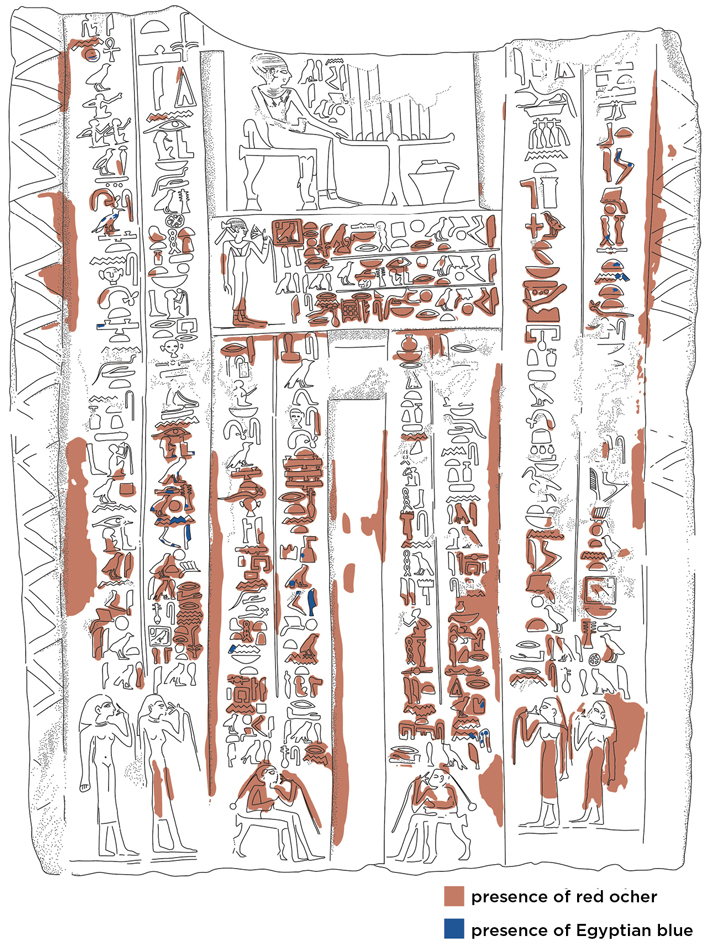

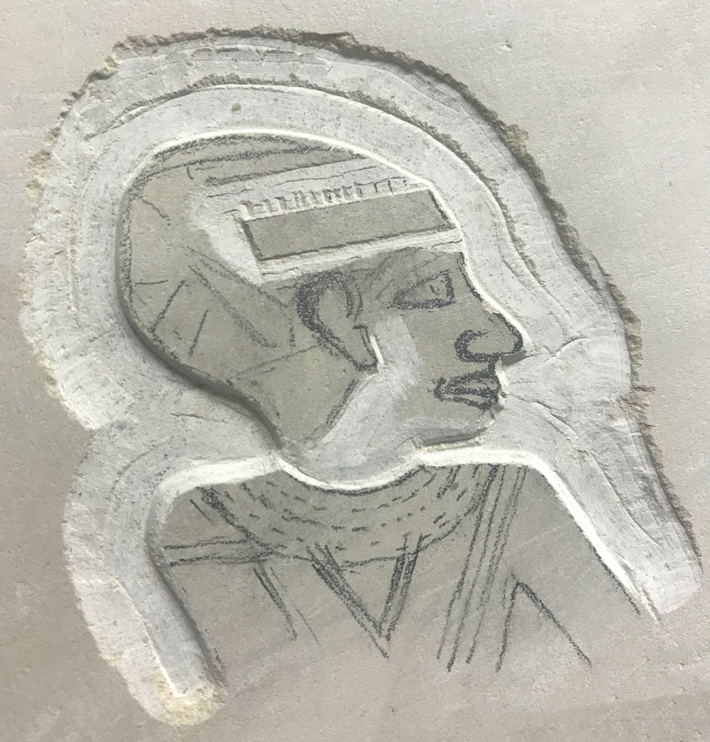

By closely examining the false door from Hemi-Ra’s tomb, which measures 32.5 inches tall by 26 inches wide, Pitkin and her colleagues could see that areas of the limestone appeared to have been smoothed and that some parts of the surface were much paler than the rest, suggesting that they had been recarved after the stela was first crafted and had not weathered to the same degree. When she looked at the door under a microscope, it became clear that it had once been painted with red ocher, most likely in an attempt to make it resemble much more expensive red granite. There was also evidence that some of the stela’s hieroglyphic text had been colored with a pigment known as Egyptian blue. However, certain parts of the door showed no sign of pigment at all. “There were no traces of red in some of the figures, but we could see red at their edges,” Pitkin says. “That was what made us really think, ‘OK, this has been tampered with.’” Her investigation ultimately revealed that Hemi-Ra’s false door was likely significantly altered not only in antiquity, but also much more recently, probably by a forger with an eye to modern sensibilities. In order to deepen their understanding of the stela, Pitkin and her colleagues attempted to re-create portions of it using periodappropriate tools, and received a crash course in the level of skill required to craft such an object—or to modify it in a way that might pass muster in the eyes of ancient Egyptians or modern connoisseurs.

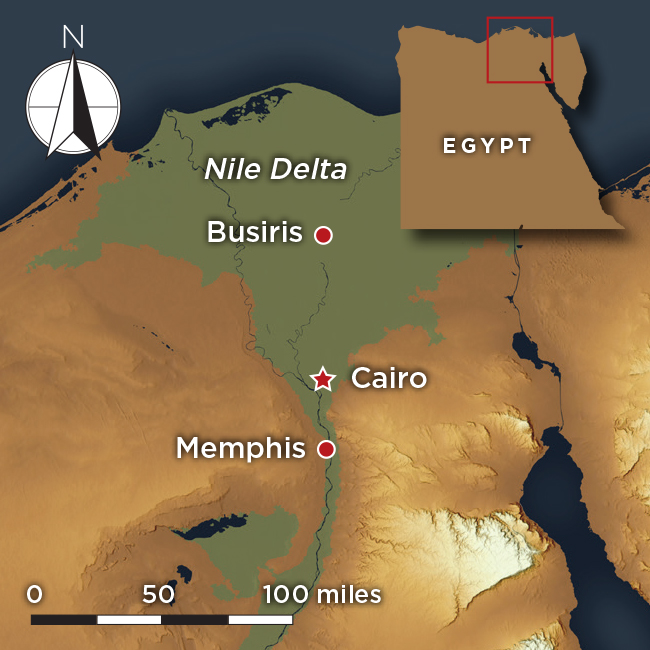

Even before delving into the question of whether the false door had been refashioned, Pitkin noted that certain qualities of the stela and the prevailing interpretation of it didn’t quite add up. Metropolitan Museum of Art Egyptologist Henry Fischer, the first researcher to write about the door, in 1976, posited that it came from Busiris, a major cult center of the funerary god Osiris in the Nile Delta. He seems to have drawn this conclusion from sections of the door’s hieroglyphic text referring to Hemi-Ra as a “priestess of Hathor” and “one revered of Hathor, the lady of Busiris.” However, Pitkin points out that this is the only known instance of this title. She suspects that this may have been a scribal mistake as the usual rendering would be “one revered of Osiris, the lord of Busiris.” There are a number of indications that the door is actually from the Memphis area, possibly the Saqqara necropolis, such as the prominence in its inscriptions given to the god Ptah-Sokar, whose cult center was located in Memphis.

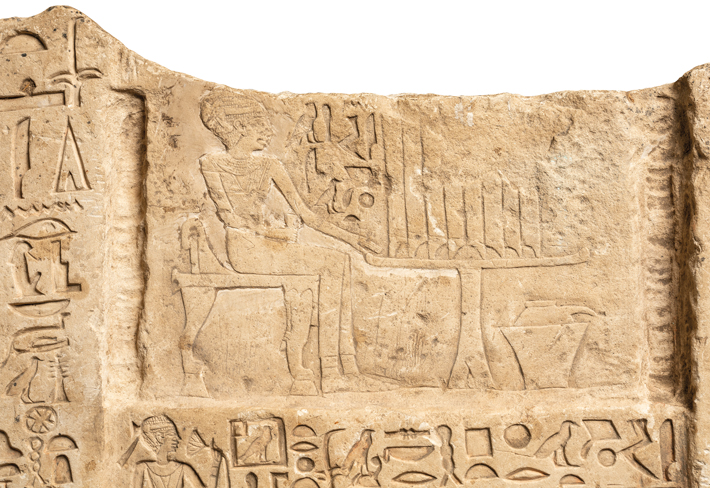

Hemi-Ra’s false door is unusual for a number of reasons, including that it was made for a woman. Of 680 known false doors and funerary stelas dating from the twentythird to twenty-first century B.C. studied by Pitkin, just 101 were designed for women. According to Fischer, the door features representations of Hemi-Ra at three distinct stages of her life. In the central panel near the top of the stela, she is depicted as a woman in her prime sitting before a table laden with offerings. At the bottom of the door, in the center, she is portrayed as a seated young girl, and as an older woman with drooping breasts on the outer edges. This is highly unusual, says Pitkin, as the deceased was typically represented only at the peak of vitality and health.

While scrutinizing the different representations of Hemi-Ra, Pitkin noticed that several have features that are not usually associated with women in ancient Egyptian art: Some of the figures at the bottom of the door have clenched fists, hold handkerchiefs, and their legs are spaced apart, all characteristics typical of men. She and other members of her team began to suspect that the door had, at least initially, been intended for the tomb of a man but was then repurposed for Hemi-Ra. This necessitated that some of the figures at the bottom be recarved to add feminine features such as longstemmed lotus flowers and longer hair. This touch-up work, however, was done sloppily, leaving some of the masculine features still visible.

Higher up the stela, in the extensive hieroglyphic inscription, Pitkin says, there is no sign of modification and Hemi-Ra’s titles are written in the feminine form. And, while the central panel does show signs of having been altered, the figure of Hemi-Ra there does not have any typically male features. Thus, Pitkin believes the stela was carved starting at the bottom and only a small portion had been completed at the time it was transferred to Hemi-Ra. “Perhaps it started to be made for a man who commissioned it and then he didn’t want or need it anymore,” she says. “Presumably, it would be cheaper to buy something like that and finish it for yourself rather than starting from scratch. The door may also have been made for a relative of Hemi-Ra, so it was available to her.”

Pitkin believes that the door was colored red only after its preparation for use in Hemi-Ra’s tomb had been completed. She argues that those parts of the door that lack traces of red ocher were likely altered in recent times, when the original coloring was no longer visible to the naked eye, and that whoever made the alterations would have had no idea that the color had ever been present. “If you wanted to keep the door looking authentic, you would repaint those areas in red—if you knew the door had been red,” says Pitkin. “But the red paint had already faded so much by that time that the person doing the recarving didn’t even know that was an issue.”

Among the areas that appear to have been recently modified, Pitkin singles out the figures at the bottom of the door with full-frontal breasts—a perspective that is extremely uncommon in two-dimensional ancient Egyptian art. She believes these changes were carried out in an effort to make the artifact more alluring by a dealer named Michel Casira who is now known to have been involved in forging antiquities and from whom the Fitzwilliam Museum acquired the door in 1909. “The breasts are something that would have triggered interest in the market because they’re so unusual,” says Pitkin.

To learn even more about how Hemi-Ra’s false door was created and altered, in December 2021 Pitkin and her colleagues at the Fitzwilliam Museum reproduced sections of it from scratch. They sourced blocks of limestone from Egypt matching the type used to make the stela and employed replica tools to carve the different parts. For Pitkin, the exercise provided an object lesson in how much painstaking work First Intermediate Period artisans expended. “The key thing we demonstrated is that there is a gross underestimation of art from the First Intermediate Period, which is too commonly dismissed as being inferior. The circumstances were very different at this time because there was no singular central royal court dictating the style of art,” she says. “There was greater opportunity to be more expressive in terms of what people wanted to depict and how it was depicted. While the style is slightly more naive than what you find during the peaks of the kingdoms, the craftsmanship involved in carving these objects and the attention to detail is mind-blowing. When you actually try to do it yourself, you get a whole new level of appreciation for the skills and dedication of the ancient craftspeople.”