In the fall of 2008, Kevin Thomas, a deputy sheriff in northern Georgia’s Jackson County, was on a routine patrol in the new River Glen subdivision. Then consisting of just a few houses under construction near the banks of the upper Oconee River, the development was still largely pristine, its gently rolling hills covered with oak and hickory trees. As he was driving along the neighborhood’s River Glen Drive, a flash of white in the woods to the east of the road caught his eye. He pulled his patrol car over and walked toward what turned out to be a mound of stones piled a foot high. “I thought, ‘Good lord, these have been here a long time,’” says Thomas. “I’ve seen piles of stones farmers make after clearing a field, and this looked different—more spread out and much older.” Curious, he searched the area and found dozens of other stone piles of various sizes, ranging from a few feet in diameter to one that was up to 30 feet wide. The individual rocks in the piles varied, too, from fist-sized to small boulders, consisting of both a quartz-rich white rock known as gneiss and a darker colored schist. The unusual complex of stone piles spread across about nine acres.

Over the years, Thomas returned to the site during his off hours and continued to find more stone piles as well as pottery sherds and other artifacts eroding out of the earth near the piles. In 2015, Thomas struck up a conversation with Joel Logan, Jackson County’s GIS manager. Logan is responsible for maintaining the county’s geographic data and had recently begun working with Johannes Loubser of the archaeology firm Stratum Unlimited to collect information on archaeological sites in the area. Although Thomas had previously been unable to interest archaeologists in the site, his description of the enigmatic stone piles in the River Glen subdivision piqued Logan’s curiosity. One day in mid-January of 2016, Thomas, Logan, and Loubser paid a visit to the site.

“I wasn’t sure what to expect,” says Loubser. He notes that piled-stone features, also known as petroforms, have often been a source of controversy among archaeologists who study the southeastern United States, many of whom assume they were left by European-American farmers clearing their fields of stones. But, like Thomas, Loubser’s first thought on visiting the site was that it was unusual and that at least the largest stone mound had very likely been made by Native Americans, not by farmers removing stones before plowing.

In researching the River Glen site, Loubser learned that an archaeologist named Gordon Midgette had recorded some of the rock structures in 1967 as part of a survey of the area, but had not made a map of the stones. In the 1990s, another team, led by University of Georgia archaeologist Jerald Ledbetter, noted a nearby turtle-shaped mound of rocks overlooking the Oconee River, but did not find the bigger complex of rock piles recorded by Midgette and later spotted by Thomas. During interviews with Logan, older members of a family that had once owned part of the property on which the stone piles were located reported that, as children in the early twentieth century, they had played among the piles, but had no notion of who had made them.

During the Mississippian period (ca. A.D. 900–1600), ancestors of both the Muscogee Creek and the Cherokee lived in this area of northern Georgia. Mississippian people throughout the Southeast practiced intensive agriculture and lived in towns that grew over time and featured large ceremonial mounds. They also seem to have practiced rituals that involved elements of a belief system shared by peoples living from present-day Illinois to Florida. If the stones had not been piled by European-American settlers, then it seemed likely that Mississippian people had built the mounds.

Loubser alerted archaeologist Russell Townsend of the Tribal Historic Preservation Office of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians to the existence of the site. Given that the stone piles lay in the path of future development, Townsend felt the group should go forward with documenting them. Loubser, Logan, and Thomas worked with a team of volunteers over the course of three seasons to expose and record the site’s 56 piled-stone features. They found that many had an unusual hexagonal shape, while at least seven appeared to be what are known as effigy mounds, which were built to resemble animals or other figures, and in this case appear to represent birds. They also discovered that the 30-foot-wide mound was built around a natural quartz outcropping and outlined the shape of a raptor with its wings folded to the side. The bird-shaped River Glen mounds seemed similar to two larger, well-known stone effigy mounds called Rock Hawk and Rock Eagle that are some 50 miles south of the site in Georgia’s Putnam County. Of uncertain age, these two mounds were also built along veins of rock quartz and had been thought to be the only bird-shaped effigy mounds east of the Mississippi River.

To Loubser’s surprise, the team also discovered pottery sherds in the mounds that suggested they were built during what archaeologists call the terminal Mississippian or Lamar period. Lasting from about 1550 to 1760, the Lamar period was believed to have been a chaotic time during which Mississippian political and social institutions collapsed in the wake of warfare and widespread disease that followed the arrival of the Spanish. During the Lamar period, people moved out of large towns and onto small farmsteads, where researchers thought they lost touch with Mississippian traditions. But Loubser felt that the builders of the River Glen stone features had been animated by a strong sense of purpose. They were likely Muscogee people associated with what scholars call the Wolfskin phase of the Late Lamar culture. The Muscogee who built stone structures on this scale, says Loubser, were a people reinvigorating cultural traditions, not abandoning them.

Efforts by the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians to raise awareness of Native American rock mounds in the Southeast, along with the discoveries at the Muscogee River Glen site, are changing how archaeologists approach piled-stone features in the region. “I’d say that even eight years ago we would have assumed most of these rock features were the result of farmers clearing their fields,” says archaeologist Scott Ashcraft of North Carolina’s Pisgah National Forest. “But with Jannie Loubser’s work and the Eastern Band encouraging us, we are taking another look.” Ashcraft says stone features are sometimes found in the woods of the Southeast in places where farmers are unlikely to have cultivated crops, such as hillsides or mountain passes. “It’s not necessarily convenient for the Forest Service to reclassify these sites,” he says, “but with what we know now, it’s something we really have to do.”

Even prominent piled-stone sites such as Rock Eagle, which has a wingspan of 120 feet at its largest, and Rock Hawk, which was once encircled by a wall 100 feet in diameter, have had their Indigenous origins questioned by locals and some scholars. After many years of excavation by several modern researchers, definitive proof of when the sites were constructed has been elusive. Extensive archaeological excavations also mean that the sites have been heavily disturbed, and, in the case of Rock Eagle, reconstructed to appear pristine in a manner that might not reflect how it appeared hundreds of years ago.

According to local oral history, around 1800 an American settler named Giles Tompkins took possession of the land on which Rock Eagle was situated. He is said to have asked local Native Americans about the site, and they are said to have replied that they did not know what its origin or significance was. “It’s probably fair to say that if they did know,” says Loubser, “they wouldn’t have told a settler.” He points out that many historic accounts suggest that Native Americans in the region made a practice of building or adding to stone piles. Eighteenth-century Irish trader James Adair, who lived among the Chickasaw, a Muscogee-speaking people who inhabited what is now Mississippi, left a detailed account of some of these stone memorials: “To perpetuate the memory of any remarkable warriors killed in the woods…every Indian traveler as he passes that way throws a stone on the place. In the woods we often see innumerable heaps of small stones in those places, where according to tradition some of their distinguished people were either killed, or buried, till the bones could be gathered.”

If the River Glen piled-stone features contained human remains, this would have important consequences. Under Georgia law, sites with buried human remains cannot be developed. Were Loubser and his team to determine that the mounds contained Native American graves, the site would be protected.

Over the course of their three field seasons, Loubser and his team excavated sections of seven of the piles. They found that they were all built above deliberately dug shallow depressions. They also found no traces of a plow zone, or soil disturbed by agriculture, near the mounds. Logan was able to locate a 1944 aerial photograph of the site that showed there were cotton fields in the area, but that a large stand of hardwood trees covered the hill where the mounds are located. “We showed pretty definitely that they were not made by farm clearing,” says Loubser. “I think the farmers avoided the area precisely because removing the stone piles would have been labor intensive.”

When the team excavated in the center of the largest raptor-shaped pile, they uncovered 61 fragments of human long bones. Immediately below the bones, they unearthed stone tools and a Wolfskin-phase bowl fragment. Similar artifacts have been found in Wolfskin-phase burial caches in natural rock outcrops. Such caches contain fragmented human remains, miniature funerary pots, and clay pipes decorated with intricate birds’ heads.

The evidence the team discovered meant that the River Glen piled-stone features constitute a cemetery under Georgia law, and plans to build houses on the site were put on hold. Logan recalls a conversation he had with one of the contractors working on the development who operated heavy excavation equipment. “I showed him some of the stones and explained their significance,” says Logan. “He told me, ‘I bulldoze and destroy stone piles like that all the time.’”

Now protected, the River Glen stone piles join a growing body of sites in northern Georgia that are transforming how scholars think about the history of the people who lived here after Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto made his way through the region between 1539 and 1543. The archaeological record shows that after the introduction of European diseases led to social instability and increased warfare, Mississippian people moved into increasingly smaller settlements and individual farmsteads. Scholars have assumed the population also collapsed around this time. “We’ve always thought that this period marked an abrupt end of Mississippian lifeways and elaborate ceremonialism,” says Loubser. But beginning in the 1990s, researchers noted that in northern Georgia, the population during the Lamar period actually grew, perhaps in part because people were migrating into the area. Five Lamar farmsteads that have been identified within a few minutes’ walk of the River Glen site are just some of the hundreds of such sites that have been located across the counties of northwestern Georgia. Very few European artifacts have been discovered at these farmsteads, suggesting local people may have been refusing to trade for Spanish goods.

The Mississippian-period site of Dyar Mound once stood on the Oconee River south of the River Glen site. Before it was flooded by a reservoir in the 1970s, the mound was extensively excavated. Recent reanalysis of radiocarbon dates from the site by a team that included Chattahoochee-Oconee National Forest archaeologist James Wettstead showed that Dyar Mound was not completely abandoned after de Soto’s expedition reached the area in the early 1540s. (See “Enduring Rites of the Mound Builders.”) It seems that even if inhabitants left the town to live in smaller settlements, they returned to Dyar Mound to practice ceremonies until at least 1670. “The Muscogee retained their cultural practices here for much longer than had been assumed,” says Wettstead. “Loubser has shown that River Glen was a sacred site at the same time.”

Their encounter with the Spanish deeply disrupted ancestral Muscogee and Cherokee peoples’ ways of life, but Loubser suggests these communities eventually rallied around ancient symbols and rituals in an effort to stave off cultural obliteration. “The people in these farmsteads were carefully creating bird petroforms and making elaborately crafted bird-headed clay pipes during a period of severe socioeconomic challenges,” says Loubser. Throughout history, people who have encountered colonizing powers have often responded to rapid social change by building societies that hark back to traditional ways of life. Sometimes they accomplish this by choosing key symbols from the past and adapting them to meet the challenges of the present. Loubser says that for people living along the upper Oconee River during the Lamar period, an important old Mississippian symbol seems to have been a bird with the wings and beak of a raptor, a motif that occurs on many artifacts found throughout the Mississippian world. It’s possible that the raptor petroforms of Rock Eagle and Rock Hawk, which are both just a few dozen miles from Dyar Mound, were also built during the Late Lamar period as part of this revitalization movement.

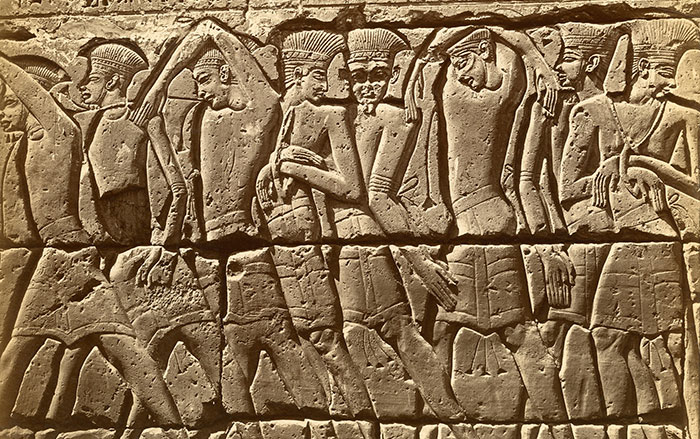

Raptors are known to have played an ancient and central role in Mississippian religious life. The eighteenth-century trader Adair wrote that while Native Americans of the Southeast considered birds of prey unclean, such birds were also believed to be very powerful. The Cherokee thought that a shadow cast by a raptor could cause disease that could only be cured through the intervention of a medicine person. Eagles were especially powerful beings and were thought to be able to either help or hinder a person on their long journey to the “Darkening Land,” or the afterlife. During out-of-body experiences, medicine people were thought to accompany the souls of the dead and to do battle with raptors that sought to prevent the souls from reaching the afterlife. Shell and copper ornaments from Mississippian sites showing raptors confronting other beings, and depictions of men dressed as eagles, suggest beliefs linked to birds of prey were of great antiquity.

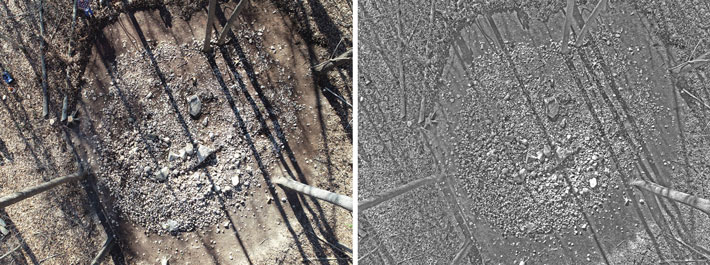

Loubser proposes that the River Glen petroforms could have been made by people from the surrounding farmsteads to memorialize confrontations between raptors and medicine people. The piles, especially the raptor forms, seem to have been constructed to be viewed from a great height, such as their builders might have imagined medicine people reaching during out-of-body experiences. “Their outlines weren’t really clear to us from the ground until we looked at drone images,” says Loubser. “Then the bird shapes jumped out.”

It is also possible that families from different farmsteads came together to pile stones to mark other important events entwined with ancient Mississippian beliefs having to do with birds and the afterlife. Loubser says that as clear as some of the bird shapes seem, the mounds probably remain unfinished. “I think they were making these petroforms until the day they left.”

Jackson County has now purchased most of the River Glen site, and officials plan to preserve the stone piles as part of a historic park. Before that happens, the human remains discovered in the large raptor petroform will be reburied after consultation with the Historic and Cultural Preservation Department of the Muscogee Nation. Discussions are now underway about how to do that properly and respectfully.

Logan often recalls his conversation with the contractor who said he bulldozed stone piles as a matter of routine. “I can’t help but think of the Native American history that is being lost with all the new development happening around Atlanta,” he says. “We were lucky that Kevin Thomas found these stones and watched over them for so long. But there could be sites like this all over the woods of the Southeast, hiding in plain sight.”