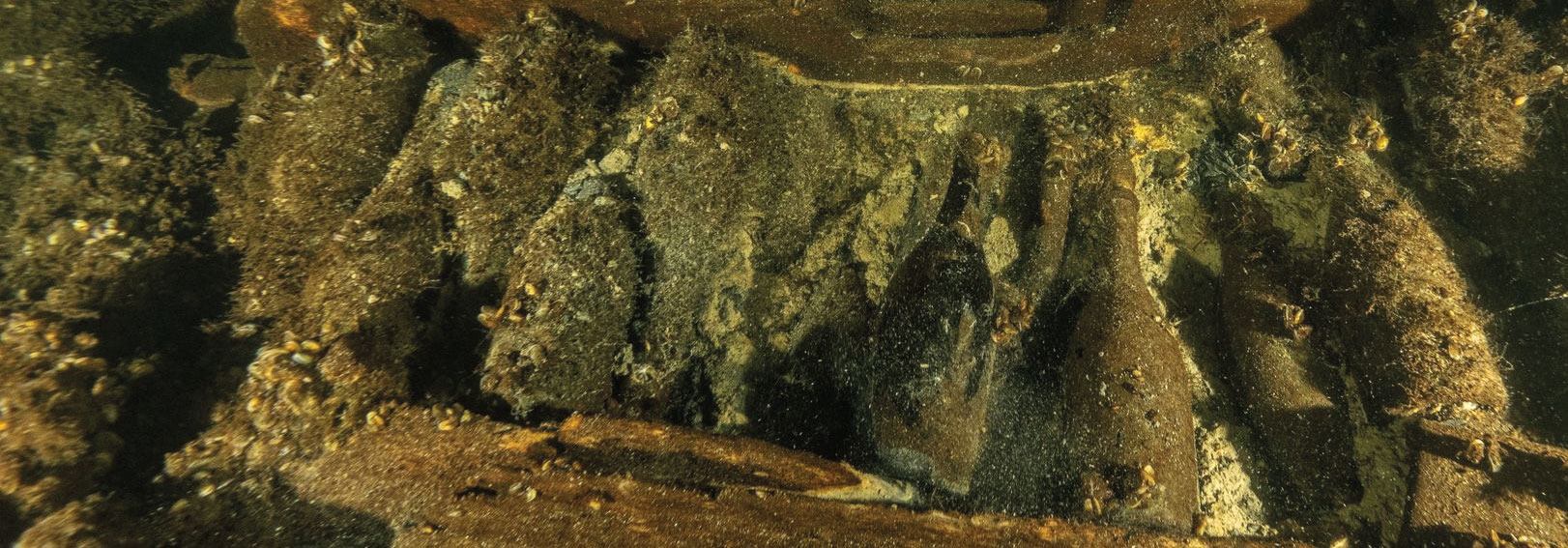

The best known maritime disaster of the past few centuries, the sinking of Titanic is remembered for the failure of an engineering marvel equipped with technological advances that were, at the time, believed to render it “practically unsinkable.” The luxury liner took some 1,500 of its 2,200 passengers, from rich and prominent aristocrats to poor immigrants, with it when it struck an iceberg and sank into waters two-and-a-half miles deep. The disaster has inspired countless songs, memorials, books, and films, as well as laws to prevent other ships from going to sea without enough lifeboats and to compel nearby ships to respond to calls for help. Discovered by a joint U.S.-French expedition led by Jean-Louis Michel and Robert D. Ballard in 1985, the wreck of Titanic proved an irresistible lure for explorers, salvagers, and aficionados. Since 1986, more than a hundred deep-sea dives to the wreck have been made, some 5,500 artifacts have been recovered by a private company for public exhibition, and a variety of films, including the James Cameron blockbuster, have been shot at depths once thought inaccessible. Over the past three decades, a variety of other deep-water projects have discovered other wrecks, from the oldest known one in the Gulf of Mexico—a copper-sheathed, early-nineteenth-century vessel found in 2012—to the German battleship Bismarck and the aircraft carrier USS Yorktown. In addition, the discovery of Titanic sparked tremendous interest from explorers and archaeologists, as it showed that the deep ocean, home to many other more or less intact and highly significant shipwrecks, had effectively been “opened up” for research and recovery. A 2012 scientific mission to Titanic used robotic vehicles equipped with sonar and cameras to create a detailed map of the wreck site, as well as high-resolution three-dimensional documentation of the fragmented ship’s various components. Where the original discovery of Titanic marked the deep ocean as the final archaeological frontier, the 2012 Titanic project signaled that archaeological standards can and must be applied to wrecks no matter where they rest. When George Bass began to excavate Cape Gelidonya in 1960, critics claimed that meaningful archaeology could not be done underwater. The five decades since have proven them wrong, even at astounding depths.