On the night of July 31, 1761, Jean de Lafargue, captain of the French East India Company ship L’Utile (“Useful”), was likely thinking of riches. In the ship’s hold were approximately 160 slaves purchased in Madagascar just days before and bound for Île de France, known today as Mauritius. It had been 80 years since the dodo had gone extinct on that Indian Ocean island, and the thriving French colony had a plantation economy in need of labor. However, though slavery was legal at the time, de Lafargue was not authorized by colonial authorities to trade in slaves.

According to the detailed account of the ship’s écrivain, or purser, as L’Utile approached the vicinity of an islet then called Île des Sables, or Sandy Island, winds kicked up to 15 or 20 knots. The ship’s two maps did not agree on the small island’s precise location, and a more prudent captain probably would have slowed and waited for daylight. But de Lafargue was in a hurry to reap his bounty. That night L’Utile struck the reef off the islet’s north end, shattering the hull. Most of the slaves, trapped in the cargo holds, drowned, though some escaped as the ship broke apart. The next morning, 123 of the 140 members of the French crew and somewhere between 60 and 80 Malagasy slaves found themselves stranded on Île des Sables—shaken and injured, but alive.

De Lafargue had some kind of nervous breakdown, according to the écrivain. First officer Barthélémy Castellan du Vernet took over, and rallied the crew to salvage food, tools, and timber from the wreck and build separate camps for the crew and the slaves. Under the first officer’s guidance, a well was dug, an oven and furnace built, and work on a new boat begun. Within two months, the makeshift vessel La Providence emerged from the remains of L’Utile. Du Vernet, before he sailed away with the crew, promised the Malagasy people that a ship would return for them. And so they waited. The few that survived waited a very long time.

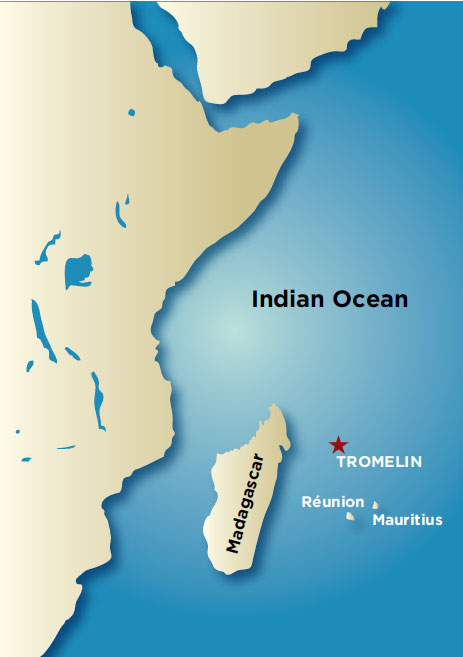

The islet, today called Tromelin Island, lies 300 miles east of Madagascar and 350 miles north of Mauritius. Shaped like a sunflower seed, it is just one-third of a square mile of sand and scrub. Today it hosts an unpaved runway, a staffed weather station, and a wildlife preserve. Hermit crabs swarm across the island in packs at night, and each year hundreds of sea turtles and countless birds arrive to lay their eggs.

Diaries, letters, and the écrivain’s account document the wreck and the two months that the French crew stayed on the island, but the Malagasy castaways left no written records. Their story would have remained almost completely untold but for Max Guérout, a former French navy officer. Guérout had captained an underwater research vessel in the late 1970s, and upon his retirement in the early 1980s founded the Naval Archaeology Research Group (known by its French acronym, GRAN), which has since studied dozens of postmedieval shipwrecks. He heard the Tromelin story from a colleague and, with support from UNESCO, began two years of archival research in 2004. “The history was so interesting that we decided to make an archaeological survey,” he says. Guérout built a team, which included experts from GRAN, the French National Institute of Preventive Archaeological Research (INRAP), and the administration of the French Southern and Antarctic Lands, to travel to the isolated islet four times—2006, 2008, 2010, and 2013—for six weeks at a stretch to examine the wreck site, excavate, and learn something about the lives of the Malagasy castaways, lives undocumented by history.

After four days at sea, La Providence arrived in Madagascar, and the crew were transferred back to Réunion Island and Mauritius. De Lafargue died in transit, leaving du Vernet to face Antoine-Marie Desforges-Boucher, the governor of Mauritius, who was furious with the violation of his prohibition on bringing slaves to his island. Du Vernet repeatedly requested to have a ship sent back to the islet, only to be denied again and again. News of the abandonment even reached Paris and caused a brief stir, but was forgotten in the wake of the Seven Years’ War (1756–1763) and the looming bankruptcy of the French East India Company. According to documents found by Guérout, du Vernet never gave up. “He was probably the only man who tried to save the people who remained on the island,” Guérout says. Finally, in 1772, in response to another request from the first officer, the minister of marine affairs agreed to send a ship. La Sauterelle arrived at Île des Sables in 1775 and sent a small boat carrying two men to the island, but it was dashed on the reef. One man swam back to the ship, the other to the island. Two more ships followed La Sauterelle, but neither was able to make landfall at the reef- and whitecap-shrouded island. At last, on November 29, 1776—more than 15 years after L’Utile wrecked—La Dauphine, captained by Jacques Marie Boudin de la Nuguy de Tromelin (from whom the island gets its current name), made contact. Only seven women and an eight-month-old boy remained.

Guérout believes that most of the 60 to 80 slaves died within the first couple of years. A group of 18 had apparently departed the island not long after they were abandoned, but it is unknown whether they ever reached Madagascar. Some 15 survivors endured for the following 10 years or so. Just months before the rescue, three men and three women, as well as the French sailor stranded from La Sauterelle (who had witnessed two failed rescue attempts himself), had left the islet on a raft with a sail of woven feathers. They were never heard from again. The testimony of the seven remaining women and the records of La Dauphine have been lost. Only the archaeology that has been conducted on the island can reveal their story of abandonment, survival, and, ultimately, community-building.

In 2006, underwater archaeologists examined the remains of the wreck, which amounted to only the heaviest items—cannons, anchors, ammunition, rigging—that were not washed away by centuries of waves and storms. A few hundred feet offshore, the divers found marks in the rocky reef where the ship struck and came to rest, confirming the account of the écrivain.

The ship’s pilot had produced a small map that indicated where the stranded crew and slaves resided, as well as the sites of the furnace and oven. With this map as a reference, Guérout and his team were able to locate bricks used to make the oven, along with dozens of nails, which indicate that boards from the ship had been burned. For the rest of that season, and across three more, the archaeologists followed the progress of the castaways from the wreck to the beach to the site where they eventually settled, at the island’s highest point, about 25 feet above sea level. “But it was also the point where the meteorological station had built its buildings,” says Guérout.

Tromelin Island is in an ideal place to monitor weather, especially cyclones, bound for Madagascar. In 1954, French authorities built a weather station there. (It was destroyed by a cyclone two years later and then rebuilt.) It is still in operation today and consists of a few buildings, cisterns, and concrete footings. Mid-twentieth century accounts of the island note that there were stone walls there extending at least a few feet out of the ground, and that the stone was mined to build the new structures. In 2006, the archaeologists found a piece of buried wall there, consisting of slabs of beach rock and chunks of coral and a layer of bird bones and ash from cooking fires.

That year, the team also found six copper plates or bowls. These items had clearly been salvaged from the wreck, and then possibly hammered into new shapes. More remarkable was how they had been repaired—some up to eight times—over the course of 15 years. “To repair a copper plate is not so easy,” says Guérout. The castaways had to cut pieces of copper from other objects for patches, drill holes through both patches and plates, and then use small rolled pieces of copper as rivets, which they then hammered into place. The repairs are reflections of patience and industry, and reminders of the passage of time.

The next excavation season, 2008, brought the bonanza the team had been hoping for: three intact buildings. “We found what was probably the kitchen, with all things well kept in each part of the building,” Guérout says. In this oval-shaped building with five-foot-thick walls, there was a stack of six more copper vessels, topped with a conch shell, and a deposit of 15 cleverly made spoons. These were cut from copper with small wings at the base that could be folded over a twig to make a handle. In total, 45 domestic objects were found there, and in another building were tools, iron tripods to hold cooking vessels, and big lead bowls—probably made from lead sheets kept on L’Utile to patch holes at sea. The large lead bowls were likely used to hold water, meaning that lead poisoning may have been a problem for the survivors. The archaeologists also found pieces of flint and the metal against which they were struck, which addresses how the castaways started and maintained fires. “Those objects make the only history we can have,” say Jean-François Rebeyrotte, a Réunion Island–based archaeologist who helped the team organize its field seasons.

A detailed analysis of some 18,000 bird bones collected from the site during the 2013 season has revealed much about the castaways’ diet. Most of the bones come from sooty terns. These seabirds once nested on the island in great numbers, but not anymore—hunting by the survivors may have contributed to the colony’s collapse. The castaways also ate bird eggs and some fish, though fishing from the island is difficult, as well as turtle meat, even though killing and eating turtles is taboo to some Malagasy communities, according to Bako Rasoarifetra, a Malagasy historian from the University of Antananarivo who joined the 2010 and 2013 expeditions.

A few small pieces of copper jewelry—a ring, a couple of bracelets, and an eighteenth-century Portuguese coin that may have been worn as a pendant—were also found, along with a pointe-démêloir, or tip-comb, for untangling hair. Slaves usually had their hair cut short, but the castaways would have been able to grow their hair out again. Traditionally, Rasoarifetra adds, a man would make a pointe-démêloir for the woman he loved. These small, personal finds suggest that at some point in their stay, the castaways came to the realization that there would be no rescue and they would have to build lives—a community—on the island. “They have passed the time of strictly surviving and they begin to live a ‘normal’ life,” Guérout says.

One significant mystery remains: the locations of the graves of those who died on the island. In 2008, two sets of human remains, which had clearly been dug up and redeposited, probably in the 1950s, were found. But no more have been located despite the team’s searching. The graves may have been disturbed or built over during construction of the weather station. Another possible explanation lies in the legend of Olivier Levasseur, a pirate known as La Buse (“The Buzzard”), who is said to have left behind a coded note leading to treasure when he was hanged in 1730. Perhaps, centuries later, enterprising workers building the weather station assumed that the coral buildings were a pirate hideout, dug through them for treasure, and cast aside artifacts or even human remains. The additional half-dozen buildings uncovered by archaeologists in 2010 and 2013 appear to support this theory, as they did not contain any artifacts. The archaeologists consider themselves lucky to have found two buildings with material inside them. According to Thomas Romon, an INRAP archaeologist who worked on each field season on Tromelin, there are probably numerous additional structures beneath the modern buildings. “We have only a very partial picture of this set,” he says.

The construction and arrangement of the castaways’ structures say a great deal about life on the island, and in some ways even reflect the psychological experience of it, according to Guérout. At the time, people across Madagascar generally lived in small huts of wood, mud, and thatch, with each family group on its own plot some distance from neighbors. Such materials were not available on Tromelin, so the people there had to make do with what was on hand. The buildings are composed of two layers: flat plates of beach sandstone planted in the ground vertically, topped by coral blocks. This construction style is unlike any Malagasy home, but it does have a direct correlate on Madagascar: burial cists. According to Rasoarifetra, traditionally, all stone buildings would have been reserved for the dead. “Psychologically, it is very interesting to understand,” says Guérout. “The people chose to live in what were, in their minds, tombs.” To Rasoarifetra, it represents another cultural shock: After surviving enslavement, the wreck, and the abandonment, they even had to overcome their own cultural prohibitions.

In addition, the buildings, rather than being separate, shared walls and were clustered in about half an acre, unlike more diffuse villages back home. The archaeologists found that the castaways had, at some point, dismantled buildings to erect a wall approximately 20 feet long, probably after a cyclone damaged the hamlet. In these ways, the structures represent systematic adaptation to the lack of space and the need for protection from cyclones, and they reflect a psychological state: grave-bound, but together, leaning upon one another.

Upon their rescue in 1776, the seven adult survivors and the child were taken to Mauritius. “What is interesting in this history is that between the moment of the wreck and the moment of the rescue, the ideas on slavery were changing,” says Guérout. In 1761, governor Desforges-Boucher had refused to send help. By 1776, the women were freed upon their arrival. The new steward of Mauritius and Réunion, Jacques Maillart-Dumesle, took three of them—the child, his mother, and her mother—into his home and had them baptized. He christened the child Moses Jacques (after himself). His mother, Semiavou, or “one who is not proud,” was renamed Eve, and the grandmother dubbed Dauphine.

The other survivors also settled in Mauritius, but nothing else is known about their lives. Analysis of the archaeological finds, according to Romon, will continue to illuminate the castaways’ technical knowledge and social and religious worlds. The team is planning a detailed publication and a museum exhibit they hope will travel across the Indian Ocean islands.

“In Malagasy belief, the land belongs to the spirits and ancestors,” says Rasoarifetra. “Archaeology is an action that awakens the earth to deliver the past.” With this in mind, at the outset of the 2013 season, Rasoarifetra arranged a ceremony. She asked her ancestors for permission for the scientists to dig on their land, and explained that they were doing it not to destroy, but rather to understand. She poured a little rum into the sand at the northeast corner of the site—the corner that traditionally belongs to the ancestors. Then every team member took a sip.