Egypt’s carefully recorded lists of rulers run pharaoh after pharaoh for almost 3,000 years. Except, that is, for a century or so around 1640 B.C. when a new group came to dominate the kingdom on the Nile, throwing the region into turmoil and ushering in a new era in Egyptian history.

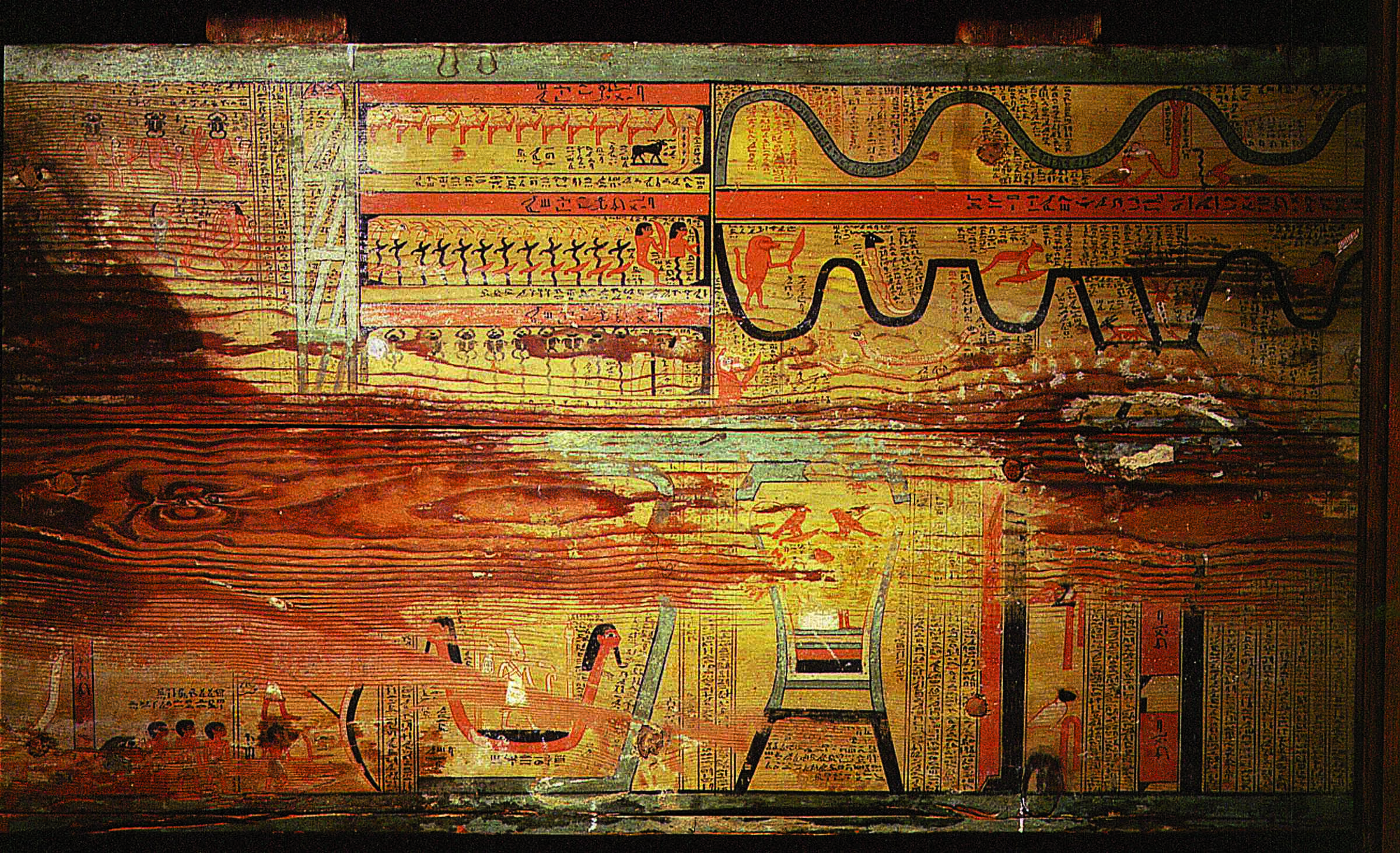

“For what cause I know not, a blast of the gods smote us; and unexpectedly, from the regions of the East, invaders of obscure race marched in confidence of victory against our land,” writes Manetho, a priest and the author of a history of Egypt called Aegyptiaca likely written in the third century B.C. Despite the fact that he is describing events at a remove of almost 1,500 years, and although his writings survive only because they are quoted in even later works, such as the first-century A.D. author Josephus’ “Against Apion,” the account is no less evocative. “By main force, they easily overpowered the rulers of the land; they then burned our cities ruthlessly, razed to the ground the temples of gods, and treated all the natives with a cruel hostility, massacring some and leading into slavery the wives and children of others, and appointing as king one of their number.”

When it came to the story of the rise and short-lived rule of these “invaders of obscure race,” for centuries scholars took for granted Manetho’s account of invasion and disruption as reproduced by Josephus. The tale was supported by other historical accounts, from tables of dynasties, rulers, and reigns found in Egyptian temples to papyrus lists of Egypt’s dynasties. Egyptologists tended to treat the period as a ripple in an otherwise unbroken stream that soon smoothed and vanished, a curious footnote in the three-millennia-long sweep of Egyptian history.

More recently, however, archaeological evidence has shifted the way Egyptologists view these invaders—the Hyksos—and their influence at a pivotal moment. The Hyksos appeared in a chaotic time after the collapse of the so-called Middle Kingdom period but before the blossoming of the New Kingdom, the five centuries of prosperity and territorial expansion familiar to many from the reigns of pharaohs such as Akhenaten and Tutankhamun. New discoveries suggest that these developments may have, at least partially, been a result of this invasion. No longer thought of by some scholars as a brief intrusion, the Hyksos may, instead, have been a force for change, pushing Egyptian civilization forward into a new era.

Hyksos, meaning “rulers of foreign lands,” stems from the manner in which the short-lived dynasty of Hyksos kings referred to itself. Their origins were unknown, and archaeologists had little to go on apart from scattered historical mentions. The Hyksos rulers seem to have written nothing down.

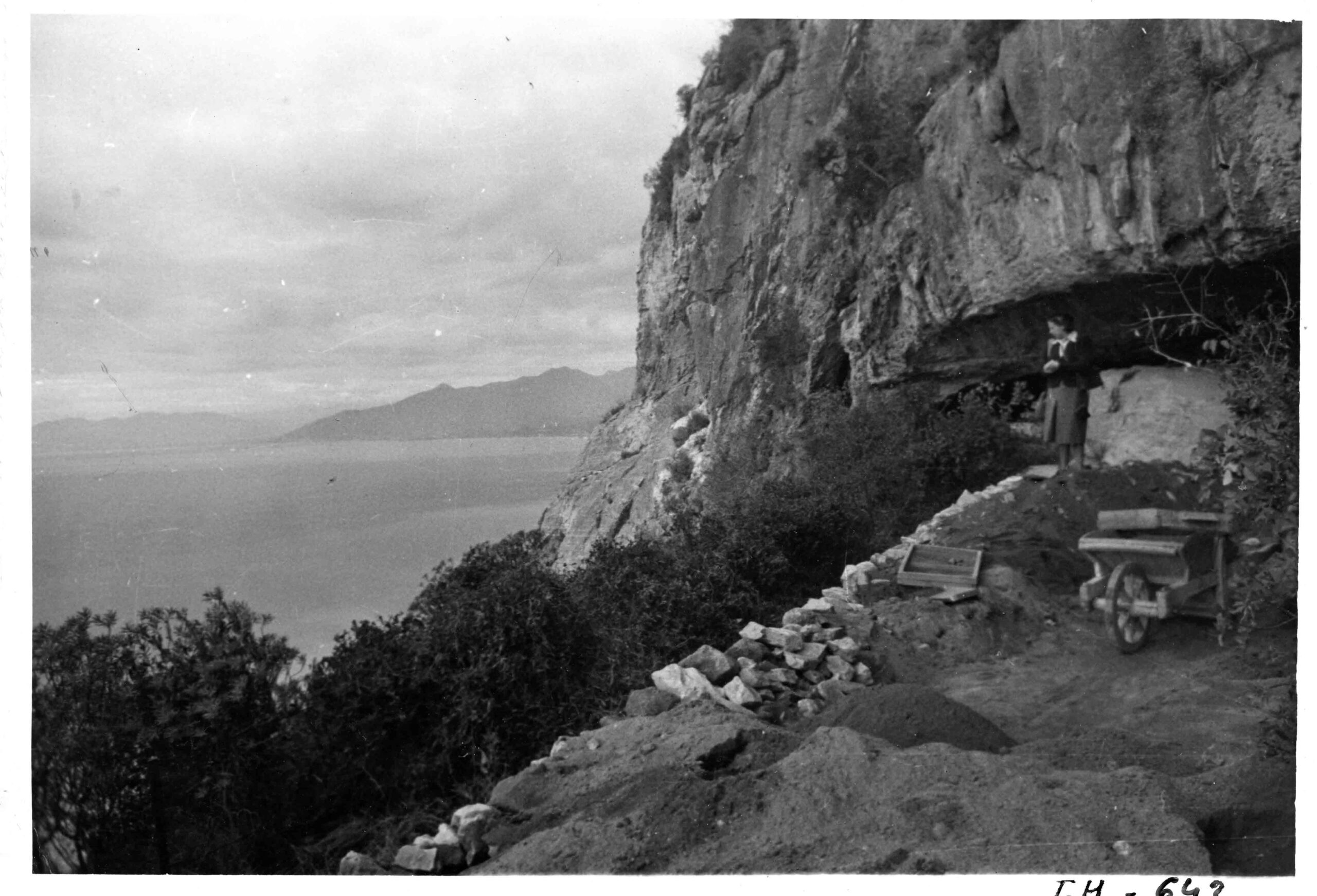

Egyptian histories refer to a Hyksos capital called Avaris. Egyptologists, tantalized by the possibility of learning what “foreign lands” the storied invaders hailed from, began looking for the city in the 1880s. But none of the sites they identified as possibilities, including nearby Tanis, a large settlement in the Nile Delta, and Pelusium, another Delta site, were a match. Some were too late to line up with the Hyksos period. Others were too small to plausibly be the capital of a dynasty that ruled all of Egypt. In the 1940s, Egyptian archaeologist Labib Habachi began digging on a mound in the Nile Delta about 40 miles northeast of Cairo called Tell el-Dab’a. Based on his initial finds, Habachi argued the site was a potential match for Avaris.

Later, Tell el-Dab’a proved to be of interest to a young Austrian archaeologist named Manfred Bietak, who started excavating there in 1966. Year after year, he returned to the site, uncovering more and more evidence of a major Egyptian metropolis that had far-ranging connections to the rest of the eastern Mediterranean. He found pottery and weaponry from the Levant and Cyprus, and statues and seals similar to those from what is now Syria. Bietak spent nearly 50 years digging at Tell el-Dab’a, until security problems following the 2011 Arab Spring in Egypt forced the Austrian Archaeological Institute to halt its excavations there.

Today, Bietak is a professor at the University of Vienna and a researcher at the Austrian Academy. He works together with his team to sort through the decades of data from Tell el-Dab’a as part of an ERC Advanced Research Grant called The Enigma of the Hyksos. He is not alone in his interest in this period of Egyptian history. Also on board are researchers looking at the impact of the Hyksos on later Egyptian culture, their identity as immigrants, how they came to power, and the reasons for their eventual downfall. Another group headed by bioarchaeologist Holger Schutkowski, based at the University of Bournemouth in the United Kingdom, plans to begin analyzing human remains from around the region and hopes to create a data set that will show where the people of Avaris came from and whether they migrated during their lifetime. What Bietak has found has convinced him that Tell el-Dab’a was, indeed, Avaris—and that the ancient accounts and generations of Egyptologists alike had it wrong.

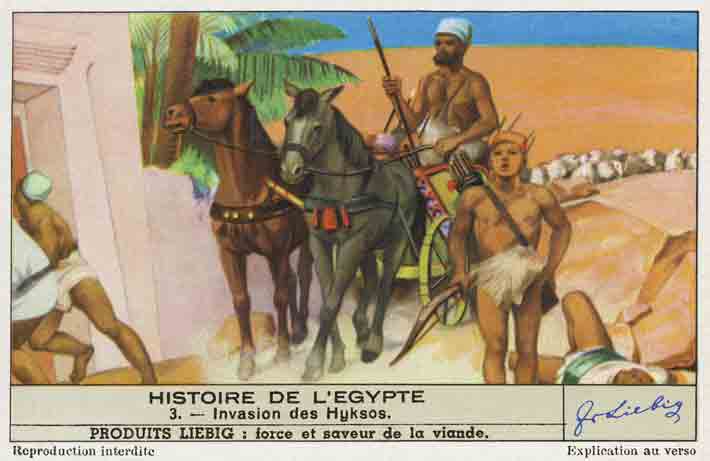

Rather than a tale of foreign imperialism, Bietak thinks the Hyksos rule was a more homegrown phenomenon, a tale of movement for economic and political reasons that would be familiar today. Immigrants from the Levant, not invaders, briefly elevated fellow immigrants, or perhaps a sympathetic elite from abroad—the Hyksos—to rule over all of Egypt. “The histories say they moved into Egypt by force and were very cruel, and led people away into slavery,” says Bietak. “But it wasn’t an invasion. After our excavations, we have no doubt it was a gradual infiltration.” Furthermore, Bietak believes this was done, at least at first, with the cooperation of the pharaohs.

And while Manetho’s bleak account of razed cities and enslaved children paints the Hyksos as a purely destructive force Egypt managed to overcome, evidence from Avaris and elsewhere suggests that they brought important innovations to the kingdom on the Nile, from the horse and chariot to new gods and an openness to the world. “In many ways, the Hyksos period is a groundbreaking period in Egyptian history,” says Kim Ryholt, an Egyptologist at the University of Copenhagen. “It’s the first time you have foreign people with foreign habits ruling in Egypt.”

Understanding the Hyksos phenomenon requires a long view of Egyptian history. The tale, Bietak argues, begins almost 600 years before they took power. Climate records show that around 2200 B.C., the world was gripped by a little ice age. In Egypt, the two centuries that followed were marked by persistent droughts. The prolonged dry spell may have led to political instability that resulted in the fragmentation of ancient Egypt’s Old Kingdom.

But Egypt wasn’t the only place affected by the change in climate. Drought also hit the desert regions to Egypt’s north and west, causing famines that may have spurred migrants from the Levant and the Libyan desert to pick up and head for the relative stability of Egypt’s annual Nilotic floods. This was the beginning of a period of intensive immigration, one the pharaohs tried to control with planned settlements and fortresses. The newcomers probably also brought their own language, which Bietak says was likely a western Semitic tongue related to Canaanite. “From the beginning, the 12th Dynasty [around 1981–1802 B.C.] employed mercenaries from western Asia,” says Bietak. “They moved into Egypt and offered their services to the local ruler in exchange for something to eat.”

Avaris, perched between the Nile’s northernmost tributaries, provided year-round access to the Mediterranean and was perfectly placed to attract these new immigrants. Evidence shows that long before the Hyksos made it their capital, Avaris was a multicultural town that served as one of ancient Egypt’s main military and commercial harbors. Over time, the port city also attracted shipbuilders, sailors, and other immigrants. “It was a local population hub mainly of people from the Levant,” Bietak says. “It blossomed with the blessing of the pharaohs during the late 12th Dynasty. During the 13th Dynasty [1802–1640 B.C.] it became more and more independent.”

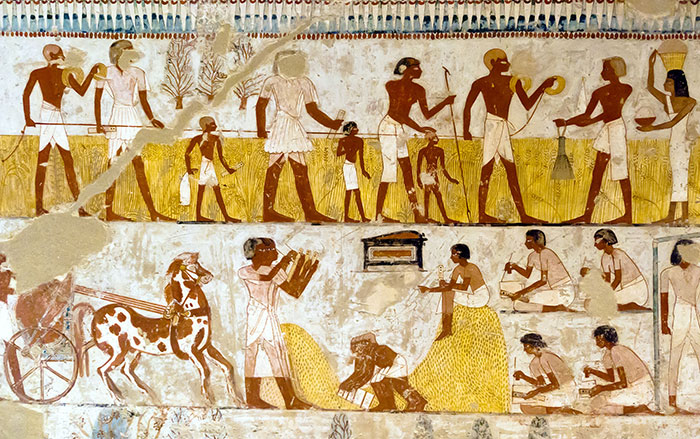

Egyptian reliefs from the period depict these new arrivals as an exotic presence. They have mushroom-shaped hairstyles and wield slings and distinctive duckbill-shaped battleaxes, unlike their lance- and shield-wielding Egyptian counterparts. Nevertheless, evidence from Bietak’s excavations suggests that these immigrants played a central role in shaping the city, including importing pottery styles, ceremonial architecture, dress codes, and non-Egyptian burial customs and religious practices such as interment in the walls of buildings and donkey sacrifices found in tombs and the courtyards of palaces and temples.

Egypt, at this time, was extending its reach to the rest of the eastern Mediterranean. Avaris’ year-round harbor played a key role. Serving as the first port of call for imported trade goods—oils from Cyprus, cedar from the mountains of Lebanon, wine from the Levant—turned Avaris into a boomtown. Cemeteries there dating from the 12th and 13th Dynasties were filled with gold, statuary, and other valuable grave goods, a sign of increasing wealth. Archaeologists have also found evidence of Egyptian influence in other cities around the Near East, perhaps left by trading colonies, embassies, or even political refugees fleeing internal conflicts in Egypt.

The religious landscape of Avaris also provides strong indications of foreign influence. Temples dedicated to storm gods from present-day Syria displaying a distinctive architecture that has little in common with typical Egyptian places of worship were constructed in Avaris beginning around 1800 B.C. For Bietak, it’s clear that the people running the show were from overseas. “The elite decide what kind of temples were constructed, so this shows us where the elite in Avaris come from,” he says. “And this type of temple comes from far, far away.” Meanwhile the city’s population established it as a rival to traditional Egyptian power centers such as Thebes, more than 300 miles to the south along the Nile, and Avaris began attracting people from elsewhere in Egypt. The stage was set for the Hyksos’ ascendance.

What exactly happened next in Avaris is still unclear, but hastily dug mass graves at the site Bietak’s team has excavated suggest that an epidemic swept through the city, perhaps a plague carried aboard one of the many ships that sailed in and out of the harbor. Later Egyptian writers called bubonic plague “the Asiatic disease,” a possible clue that the epidemic may have been introduced by arrivals from the Levant. Bietak’s excavations also show that the local palace burned to the ground toward the end of the 14th Dynasty, around 1640 B.C. It was then that the first Hyksos kings made their appearance in the historical record.

Bietak believes that a small group of foreigners used Avaris and its sympathetic, culturally similar population as a staging ground for a takeover. “There was no conquest, but rather an encroachment and concentration of people from west Asia that had already created a power base for a foreign elite,” Bietak says. From Avaris, the Hyksos rapidly expanded their rule. For a brief period, in the 15th Dynasty (around 1630–1523 B.C.), the Hyksos dominion stretched to envelop central Egypt. The Hyksos’ rise was reflected in Avaris, too. The city’s footprint nearly tripled, and at its height, the city was home to an estimated 25,000 people, spread out over a square mile of bustling, crowded, stinking cityscape. (Archaeologists have found neither plumbing nor toilets there.) “It was one of the largest cities in the ancient Near East, not just Egypt,” says Irene Forstner-Müller, an Austrian Institute of Archaeology researcher who took over the Tell el-Dab’a excavations in 2009 and used remote sensing to map Avaris’ unexcavated stretches. “The size of the town is amazing,” says Bietak.

The Hyksos’ adversaries in Thebes weren’t content with their vassal status for long. The Thebans fought back fiercely, freeing themselves and cutting Avaris off from the rest of Egypt. Fighting between Avaris and Thebes plunged Egypt into a state of civil war. According to contemporary inscriptions and Nubian pottery found in Avaris, the Hyksos seem to have forged an alliance with the Nubians, far to the south in what is now Sudan, in a vain attempt to crush Thebes from two sides. There’s even evidence of Hyksos axes in action. Bietak says the skull injuries on the remains of the Theban king Seqenenre, who ruled during the era of conflict with the Hyksos, are consistent with the duckbilled ax blades wielded by Hyksos warriors.

During one of his last excavation seasons, Bietak made a grisly discovery that dates to this violent moment in Egyptian history. In a series of pits dug near the forecourt of a Hyksos-era palace in Avaris, just in front of the throne room, Bietak found 16 severed right hands. He suggests that the amputated appendages were trophies taken by Hyksos soldiers in battle and redeemed later for a cash reward, a tradition their Egyptian opponents may have adopted as well. Severed hands exchanged for so-called “gold of valor” are a frequent feature on the walls of post-Hyksos Egyptian tombs and victory scenes on temple walls.

Perhaps surprisingly, the Hyksos’ rise to power was actually the beginning of a long decline for Avaris. Bietak suggests that the city was gradually cut off from the trade networks Egypt offered. Without gold, ivory, and precious woods from Nubia or flint from Upper Egypt, the people of Avaris had nothing to offer their trading partners around the eastern Mediterranean. Eventually, the population grew so desperate they looted elite cemeteries in nearby Memphis. “The Thebans closed the connection between the Hyksos and Sudan. There were none of the coveted commodities from Africa that had put Egypt in a strong commercial position,” Bietak says. “That explains why the Hyksos started looting cemeteries.”

To Bietak, the archaeological evidence of Avaris’ decline provides further proof that the Hyksos were locally based. If they were invaders from the Levant, his reasoning goes, they would have continued to trade with their base back home. Instead, they were soon isolated and grew increasingly impoverished. Project ceramics specialist Sarah Vilain says at this time there was a decline in the amount of imported pottery. As if in response, local potters began producing knockoffs. “You have Levantine shapes with Cypriot decoration, but local materials and craftsmanship,” she explains. Even the weaponry used during the Hyksos period was of lower quality. After the city could no longer afford tin imported from the Levant, weapons were made of pure copper, rather than bronze.

In about 1550 B.C., the Theban pharaoh Ahmose (r. 1550–1525 B.C.) launched a campaign to seize Avaris and crush the Hyksos once and for all. Manetho, the same source who had described the Hyksos as invaders, claims Ahmose, the first New Kingdom pharaoh, marched on Avaris at the head of an army 480,000 men strong—yet still failed to take the city. Finally, however, Avaris was captured. According to Manetho, the Hyksos agreed to leave Egypt willingly. According to reliefs celebrating the pharaoh’s victory, though, the dynasty’s end was bloodier. In Ahmose’s temple at Abydos, for example, there are scenes of battles and severed hands. Excavations show Avaris’ central palace was burned again. The defeated city never recovered. “Avaris was conquered and partly abandoned by the 18th Dynasty,” around 1550 B.C., Bietak says. “Its people were not expelled, but distributed all over the country as slaves and soldiers.” Pottery uncovered at Avaris suggests some also stayed behind.

Bietak’s analysis of Avaris isn’t without controversy. His careful dating of the site is based on evidence including cylinder seals, architectural styles, pottery, and papyrus scraps. But when researchers tested grass seeds preserved at the site using radiocarbon dating techniques, the results were off by nearly a century—a significant gap, given the relatively short reign of the Hyksos kings. Bietak is convinced the radiocarbon dates are incorrect, whether because of the samples that were used, the influence of geography on the site’s chemistry, or atmospheric changes. “In historical periods, historical-archaeological methods are more reliable tools,” he says. Ryholt says the dating remains an open question, and that not all Egyptologists share Bietak’s confidence. “Since the site is so pivotal, if we have to redate it, palaces we thought were Hyksos may turn out to be pre-Hyksos,” Ryholt says. “There’s still a lot of research to be done, and some of the questions may be difficult to answer. But that doesn’t mean they shouldn’t be asked.”

Centuries after their rise and fall, the Hyksos were still a bitter memory for the Egyptians. Hatshepsut, a woman who ruled as pharaoh from 1473 to 1458 B.C., boasted in inscriptions that she restored temples neglected under the Hyksos and reinvigorated disrupted trade routes. “The anti-Hyksos propaganda doesn’t begin immediately,” Forstner-Müller says. “It starts under Hatshepsut, almost 80 years later.” Their names were removed from or left off the king lists that feature in many ancient Egyptian temples. Fifteen centuries later, historians such as Manetho and Josephus still fixated on the episode. “The Hyksos came to represent a trauma for the Egyptians, a trauma so heartfelt the Egyptians were still writing about this in the third century B.C.,” Ryholt says. “It would be interesting to know why.”

And yet, as Bietak and his team continue their work, they are discovering evidence that the Hyksos played a pivotal role in linking Egypt to cultural phenomena in the rest of the Mediterranean and in a number of innovations that came to define Egyptian culture in later periods. “The Hyksos had a lasting influence on Egyptian culture and ideology,” says Anna-Latifa Mourad, a researcher who is part of the Enigma of the Hyksos project.

Some of the changes the Hyksos introduced were obvious and dramatic. The earliest horse skeleton ever found in Egypt belongs to a mare buried within a Hyksos-era palace in Avaris, in a corridor directly behind the throne room. “With the horse comes the iconography of the horse, deities, and technology related to the horse, like the composite bow and the chariot,” says Mourad. “Things we initially assumed to be Egyptian innovations might actually have been inspired by interactions in the Delta.”

Other Hyksos influences were subtler than horses and chariots, but nonetheless reached deep into Egyptian culture, politics, religion, and economics. For example, the Hyksos seem to have introduced long-distance diplomacy. Excavations have uncovered Akkadian seal impressions and a letter in a southern Mesopotamian script. And the temples and gods imported from the Near East to Egypt in the centuries leading up to the Hyksos period did not disappear when the “rulers of foreign lands” were toppled. Mourad says clay seals found at Avaris show that the Hyksos introduced gods such as Baal, a deity common in the Near East. Baal’s attributes were combined with the Egyptian god of the desert, Set. “Baal was chosen for his links to trade, kingship, and the sea,” Mourad says. “The evidence strongly suggests the Hyksos looked at him as a patron deity.”

But more than that, the effort it took to defeat Avaris gave the rest of Egypt a strong push toward a new era of openness and assertiveness. The city’s fall marked the beginning of the New Kingdom, considered the peak of ancient Egyptian prosperity and power. Ryholt suggests that the century of fighting between the Hyksos and people from other parts of Egypt also created a new military culture. Before the Hyksos, Egyptian pharaohs had no standing army. “After two or three generations of war, they developed a hierarchy of soldiers and officers and a standing fleet, chariotry, and infantry,” Ryholt says. Once the Hyksos were defeated, Egypt’s rulers began using their newly acquired military might to launch regular, and often successful, invasions of their neighbors. Says Ryholt, “The Hyksos had a big impact. Indirectly, they laid the foundations for the Egyptian Empire.”