Eretria, one of ancient Greece’s most prominent and influential city-states during the sixth and fifth centuries b.c., lay just off the mainland on the island of Euboea. Meaning “town of rowers,” Eretria was among the first Greek cities to establish colonies around the Mediterranean, including, as early as the eighth century b.c., those at Cumae and Pithecusae on the Bay of Naples. The Eretrians’ most sacred place—and one of the most renowned religious sites in the ancient Greek world—was the Sanctuary of Artemis Amarysia. Every spring, the Eretrians paraded out of their city to the sanctuary en masse to celebrate the goddess’ festival. The first-century b.c. geographer Strabo records that the processions featured 3,000 armed soldiers, 600 cavalry, and 60 war chariots. This parade would have been followed by dancers, musicians, and townsfolk who marched to the Temple of Artemis, or the Artemision, within the sanctuary to sacrifice animals, offer gifts, and perform rituals in the goddess’ honor. In addition to the temple, the sanctuary also housed the city’s sacred treasuries and served as a sort of legal bulletin board, where stelas inscribed with various laws and treaties were erected.

Archaeologists first explored Eretria in the late nineteenth century and discovered some of the city’s monuments, including several temples, a gymnasium, a theater, and sections of the city walls. They also attempted to locate the Artemision. Although several ancient writers mention the sanctuary, Strabo provided the best clue to its whereabouts, noting that it was located in a village called Amarynthos precisely seven stades—a distance equal to about eight-tenths of a mile—from Eretria’s walls. Once archaeologists had uncovered these walls, they had a starting place from which to orient their excavations.

During the first wave of investigation at the end of the nineteenth century and into the early twentieth, a few sites on Eretria’s outskirts seemed promising. All turned out to be dead ends. Strangely, researchers could find no trace of the complex in or around the city. As the decades progressed and evidence of the sanctuary remained elusive, some scholars began to doubt it would ever be found—and even whether it had actually existed. The sanctuary’s location would become an enigma that would vex archaeologists for more than a century.

In the late 1960s, when the search for the Artemision was already more than six decades old, a young doctoral student in classics named Denis Knoepfler joined a Swiss archaeological team working in Eretria. He soon took up the challenge of finding the temple and eventually altered the course of the investigation entirely. “The history of Eretria was particularly interesting to me,” says Knoepfler, who is now an honorary professor at the University of Neuchâtel and professor emeritus at the College of France, “but many questions remained unanswered, or at least shrouded in mystery, especially the location of the Sanctuary of Artemis at Amarynthos.” The quest would occupy him for the next 50 years.

Knoepfler reconnoitered the Euboean countryside for signs of the sanctuary, taking photographs and documenting instances where marble blocks had been reused in medieval constructions, which suggested that ancient buildings were likely buried nearby. He began to focus on the landscape around a village called Vathia, seven miles east of Eretria, where a small thirteenth- or fourteenth-century Byzantine church that was a patchwork of repurposed ancient blocks still stood. Knoepfler wasn’t the first scholar whose interest had been piqued by the area. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, various discoveries were made in the fields near the neighboring towns of Vathia and Kato (Lower) Vathia, especially at the base of a small coastal rise known as Paleoekklisies (“old chapels”) Hill. These included inscriptions bearing the name Artemis and a relief sculpture depicting the goddess, her twin brother, Apollo, and their mother, Leto. However, since this spot was much farther away from Eretria than the one Strabo had described, most archaeologists dismissed it as a possible site of the temple. “These discoveries should have pushed archaeologists to look for the sanctuary in Vathia at the end of the nineteenth century, but nobody did, and I don’t know why,” says archaeologist Sylvian Fachard, director of the Swiss School of Archaeology in Greece (ESAG). “As classical archaeologists often were, they were kind of blinded by Strabo’s text and didn’t want to criticize it.”

After evaluating his own research and that of late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century scholars, Knoepfler became convinced that the Artemision was not in fact immediately outside Eretria. He thought it could only be near Kato Vathia. In 1969, he filed a report with the Swiss Archaeological Mission. “As a result of my investigations,” Knoepfler says, “I believed that the sanctuary must be at the foot of Paleoekklisies Hill and that it was appropriate to undertake surveys there to finally bring to light the Sanctuary of Artemis Amarysia.” His report would have little immediate effect and would not even be made public until 2018.

Despite this lack of recognition, Knoepfler continued his research over the next two decades. His most pressing obstacle was resolving the discrepancy between Strabo’s text and the lack of archaeological evidence. Before persuading archaeologists that the sanctuary might be near Kato Vathia, which lies at the foot of the hill, Knoepfler had to determine how Strabo could have been so misguided. He ultimately proposed an ingenious theory, which he published in a 1988 article. Knoepfler suggested that the acclaimed ancient author’s writing had been wrong—sort of. It was not Strabo himself who had erred, Knoepfler claimed, but rather a medieval monk who must have made a mistake when transcribing Strabo’s Geographica. The problem was rooted in the ancient Greek numbering system. The Greeks didn’t have numerals, but used letters in place of numbers. Alpha—the first letter of the Greek alphabet—was used for the number one, beta for two, gamma for three, and so forth. Strabo’s text recorded that the Artemision was located seven stades from Eretria, seven being denoted by the letter zeta. Knoepfler wondered if instead of zeta (ζ), the original text might have actually contained the very similar letter xi (ξ), which has a much greater numeric value. One letter may have been accidentally swapped for the other, perhaps by tired eyes working by candlelight, and the new manuscript, with the inadvertent typo, was passed down for centuries. Perhaps Strabo’s original text actually stated that the Artemision lay 60 stades from Eretria, not seven. This would place it exactly in the area of Kato Vathia. Archaeologists had been looking in the wrong place for at least 100 years.

Knoepfler’s resolution to the “Strabo problem” wasn’t universally accepted. “The article aroused various reactions,” he says. “Most of them were positive, but others were more critical, and some were even indignant that I would disrespect Strabo by proposing to rectify his text.” In another curious case of indifference, after Knoepfler’s bold theory was published, nothing happened for almost two more decades. “During the investigation, there were inevitably moments of doubt about the possibility of ever finding the sanctuary at Amarynthos,” he says.

Fachard joined the search in the early 2000s. While conducting his own archaeological research in Euboea, he had become aware of an alarming development. The island was experiencing a building boom, with new houses appearing each year, especially in Kato Vathia near Paleoekklisies Hill. Fachard approached Knoepfler about reinvigorating his pursuit of the Artemision before it was destroyed by modern construction. “I said, ‘Let’s join forces and find it, because they’re building around here, and it might be too late in a decade or two,’” Fachard says. “The sanctuary was a must for me.”

In 2003 and 2004, ESAG, in collaboration with Greek authorities, conducted a geophysical survey around Paleoekklisies Hill to identify traces of buried ancient buildings. In 2006, they received a permit to dig in the area of their survey that seemed to have the greatest potential. The team uncovered ancient building material, houses, and graves; however, they were from the wrong time period. There was a long history of settlement on Paleoekklisies Hill dating back to the third millennium b.c. In fact, in the second millennium b.c., the site appears to have been called Amarynthos. A clay tablet found in the ancient city of Thebes that is inscribed in the Bronze Age Linear B script seems to identify the site as a-ma-ru-to, an earlier form of Amarynthos.

The objects and structures unearthed in the test trench by the team all dated to the Bronze Age (3200–1200 b.c.), hundreds of years before the Sanctuary of Artemis was purportedly built. There was nothing there that might potentially be linked with the Eretrians’ Artemision. For Knoepfler and Fachard, the trail appeared to have gone cold. Just when they seemed to be out of options, though, the investigation took an unexpected and intriguing turn. “That’s when the whole Hollywood movie–type thing started,” Fachard says.

Late one afternoon toward the end of the 2006 dig season, a local resident approached Fachard in a car, rolled down his window, and pointed to a construction site near the base of Paleoekklisies Hill. “He said, ‘You should have a look at that villa that they’re building over there. You’ll find interesting stuff,’” Fachard says. He and Knoepfler wandered over to the site at the end of the day after the construction crew had left. Amid a pile of stones and ancient pottery heaped at the edge of the villa’s foundation trench, they noticed a large marble block, roughly five feet long and about a foot and a half high. As they examined and photographed the block, they observed tool marks and could see that its corners had been angled in the same way that ancient Greek builders shaped their building blocks. “I thought that it had surely come from a major building,” says Fachard. “It was the first time since the nineteenth century that such a block had popped up at the foot of the hill. For me, it was a no-brainer—I knew the sanctuary was there.”

Given the late hour, the two decided to return the next day to ask questions and reexamine the block and the property. When they arrived early the following morning, however, all traces of the block were gone. The most promising proof of the temple’s location uncovered in a century of searching had vanished overnight. This was not so unusual. As more and more modern villas were being built in Euboea, construction workers frequently uncovered evidence of ancient structures buried beneath the properties. This sort of material was often surreptitiously disposed of to avoid government involvement, rescue excavations, and possible confiscation of the land. “They did what they have been doing for decades,” Fachard says. “Whenever they found something ancient when they were building a house, they would bury the remains.” Fachard had been fortunate enough, though, to have had the opportunity to quickly assess the marble block. Had he not visited the site the previous evening, the hunt for the Temple of Artemis might have come to an end right then and there.

The team was rejuvenated by what Knoepfler and Fachard had seen. The next year, although they weren’t able to excavate the private property where the block had been briefly spotted, they received a permit to investigate an adjacent parcel of land. For most of their monthlong dig, to their great dismay, they uncovered no additional evidence of the Artemision. “For three and half weeks, there was literally nothing,” says Fachard. It seemed increasingly likely that modern construction had obliterated all that was left of the temple complex. “I began to fear that I wouldn’t live long enough to witness its discovery, either there, in the most likely location, or somewhere nearby,” says Knoepfler. Then, as the team was preparing to end their season and cleaning their trench, a sizable clump of dirt suddenly detached from the side. When the dust settled, ESAG archaeologist Thierry Theurillat saw part of a large marble block protruding from the trench wall, nearly seven feet below ground level. “It was a second stroke of luck,” says Fachard. “If we had put our trench just four inches away, we never would have found this thing.” The block was only a small piece of what was to come—it was actually part of a wall belonging to a 225-foot-long stoa, a type of colonnaded public building, that dates to the fourth century b.c. This was the first in situ evidence that something extraordinary had once stood at the foot of Paleoekklisies Hill. “I was able to witness the miraculous discovery in person after days and days of fruitless excavations,” Knoepfler says. “This was something that filled me with joy and pride.”

However, just as the team was close to finally confirming the location of the Artemision, they hit yet another snag. All archaeological work abruptly ceased as landowners feared for their properties. ESAG’s researchers were left to agonize over the fate of the endangered site. “It was really depressing,” Fachard says. But when they were finally able to return, it would be well worth the wait.

For the past dozen years, the ESAG team and its Greek partners have been excavating in Kato Vathia, which is today officially known as Amarynthos, near the site where they found the stoa in 2007. The team was led from 2012 to 2021 by ESAG’s then-director Karl Reber. The Swiss government has purchased more than a dozen properties near Paleoekklisies Hill in order to eliminate obstacles to excavation imposed by private landowners. As their study area has grown, the team has uncovered a series of structures dating to between the twelfth century b.c. and third century a.d., including an additional porticoed stoa as well as several smaller buildings known as oikoi. At first, though, it remained unclear exactly what they were excavating. “We had very cool stuff, but people were saying, ‘Fine, you’ve got great things, but that could be a deme [a rural village]. How do you know it’s the sanctuary?’” Fachard says. “We didn’t have a temple.”

In 2017, that all changed. The first major discovery came in the form of a seemingly pedestrian artifact—a simple terracotta roof tile. Millions of fragments of roof tiles have been found at thousands of sites across Greece—they are commonplace. This one, however, was not. As archaeologists cleaned the dirt-caked tile, they noticed it was stamped with a tantalizing word—Artemidos, meaning “of or belonging to Artemis” in ancient Greek. This was clear evidence that the site had been associated with the goddess.

Shortly thereafter, as they were excavating a shallow well nearby, they came across a staircase. The stairs leading to the bottom of the well had been constructed during the second century a.d. using ancient stelas and statue bases that had once stood nearby. Some of these contained dedicatory inscriptions to Artemis, Apollo, and Leto. One stela bore a decree announcing a political union between Eretria and the neighboring city of Styra. The last line of the inscription explicitly stated that the stela displaying the agreement was to be erected in a particular place—the Sanctuary of Artemis at Amarynthos. “We had it!” says Fachard. “That was the proof—the tile and the inscription.” At last, the 120-year-old mystery had been solved. But the story wasn’t over yet.

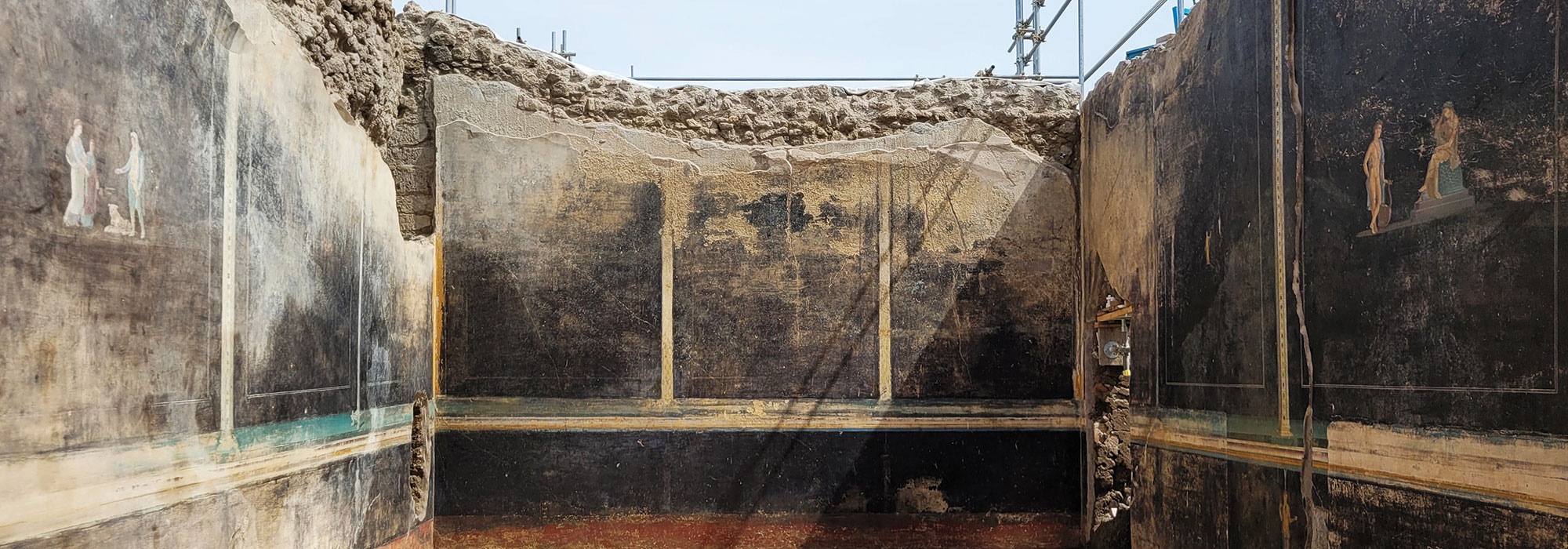

In 2020, at the heart of the sanctuary, the team uncovered the temple that once served as the center of worship of Artemis Amarysia. The ruins had, incredibly, managed to survive the construction of modern villas directly atop them. The site’s earliest known temple to Artemis was a 100-foot-long building with an apse that was erected toward the end of the eighth century b.c., although a smaller structure whose purpose is unknown had existed at the same location several hundred years earlier.

As archaeologists began to excavate the temple, they slowly exposed objects buried within its ruins. The artifacts seemed countless and almost all were completely intact. The team would eventually uncover a trove of more than 700 objects. “It’s an unimaginable discovery that impressed us all,” says ESAG archaeologist Tamara Saggini, “on the one hand because of the state of preservation and, on the other hand, because of the size of the deposit, its exceptional variety, and the rareness of many of the objects discovered.”

The relics had all been left as gifts for the goddess in the early temple, but this building was destroyed by a massive fire toward the end of the sixth century b.c. When a new, rectangular temple was constructed, the Eretrians collected the votives strewn around the ruined building, added more offerings, and buried them in the ground, sealing them beneath the floor of the new temple. Archaeologists found ceramic and bronze vases of all shapes and sizes, small terracotta figurines, weapons and pieces of armor, and jewelry, including pendants and beads made from silver, gold, ivory, faience, amber, and glass. There were even remnants of a trunk full of fabric. “I think what really stands out in the deposit is the textiles,” says Saggini. “It’s so rare to retrieve this kind of perishable material and even more so to be able to gather more than one hundred pieces of fabric.”

One of the more expertly carved artifacts is a foot-tall limestone statue of a woman holding what appears to be a fawn. This may represent an Eretrian woman coming to the sanctuary to offer the animal as a sacrifice to Artemis, or it may depict the goddess herself, who was often portrayed as a huntress and was commonly associated with deer. Fachard believes the statue could be an important piece of evidence in understanding how the Eretrians viewed and worshipped Artemis Amarysia.

The quantity of objects in the votive deposit and their excellent condition has afforded archaeologists an unprecedented look at the kinds of activities that took place in the sanctuary and at who participated in the rituals and sought the goddess’ favor. While Artemis would have been worshipped by people from across the Eretrian countryside, it seems that women had a particularly intimate link with her cult. “Like the gift of linen and clothes, or the giving of jewelry, most of the objects and activities are related to the sphere of women,” Fachard says. The sanctuary would have had close connections to important rites of passage in a woman’s life, such as entering adolescence, marriage, and childbirth. Thus, Artemis was seen by Eretrians as much more than simply the goddess of the hunt. Fachard imagines that the delicate statue of the woman holding the fawn can be interpreted as Artemis sheltering a young animal and, consequently, as a metaphor for her special role as a protector of Eretrian youth, especially girls.

The search for the Artemision has been a long and extraordinary journey, requiring ingenious thinking, tremendous persistence, uncanny timing, and more than a little bit of luck. Had Knoepfler and Fachard not acted so quickly to investigate the tip about the marble block at the construction site, the pursuit of the Sanctuary of Artemis Amarysia may have ended more than a decade ago. “It was a window of literally just a few hours,” Fachard says, “and without that discovery, the sanctuary would probably still be buried underground.” Once teetering dangerously close to destruction by modern development and potentially being lost forever, the Eretrians’ most sacred place of worship is now secure.

Slideshow: Offerings to Artemis