As the Nile slices through the barren desert of North Africa, it runs straight north, with the exception of one magnificent curve, reminiscent of a giant S. This stretch of the river winds through northern Sudan approximately 250 miles south of the Egyptian border. Known as the Great Bend of the Nile, it marks the southern boundary of Nubia, a region that stretches from Sudan into southern Egypt and has been home to the Nubian people for millennia.

The modern Nubian town of Kerma sits at the northern end of the Great Bend. It is a bustling riverside community teeming with animated produce markets and fishing boats piled high with six-foot Nile carp. At the center of the town rises a five-story mudbrick tower, or deffufa in the Nubian language, which has kept watch there for more than 4,000 years. Consisting of multiple levels, an interior staircase leading to a rooftop platform, and a series of subterranean chambers, the Deffufa once functioned as a temple and the religious center of a Nubian city that was founded there around 2500 B.C. on what was once an island in the middle of the Nile. Also known as Kerma, it was the earliest urban center in Africa outside Egypt.

Below the Deffufa, archaeologist Charles Bonnet of the University of Geneva has spent five decades excavating Kerma and its necropolis. Much of what scholars know of early Nubian history comes from ancient Egyptian sources, and, for a time, some believed Kerma was simply an Egyptian colonial outpost. The pharaoh Thutmose I (r. ca. 1504–1492 B.C.) did indeed invade Nubia, and his successors ruled there for centuries, just as later Nubian kings invaded and held Egypt during the 25th Dynasty (ca. 712–664 B.C.). The ancient history of Egyptians and Nubians is, thus, closely intertwined. But Bonnet’s excavations are offering a markedly Nubian perspective on the earliest days of Kerma and its role as the capital of a far-reaching kingdom that dominated the Nile south of Egypt. His finds there and at a neighboring ancient settlement known as Dukki Gel suggest that this urban center was an ethnic melting pot, with origins tied to a complex web of cultures native to both the Sahara, and, farther south, parts of central Africa. These discoveries have gradually revealed the complex nature of a powerful African kingdom.

Bonnet began working at Kerma in 1976, some 50 years after Egyptologist George Reisner, the first archaeologist to dig at the site, closed his excavations. As the leader of the joint Harvard University–Boston Museum of Fine Arts Expedition, Reisner had spent many years directing excavations at the Great Pyramid of Giza and working in southern Egypt, where he developed an interest in ancient Nubian culture and in connecting its history to that of the Egyptians. “Reisner thought the place to find new Egyptian art would be in northern Sudan,” says Larry Berman, curator of Egyptology at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. In 1913, by request of the Sudanese Antiquity Center in Khartoum, Reisner was directed to Kerma, which, at the time, was only vaguely known to Westerners from the accounts of nineteenth-century European explorers. He was completely unprepared for what was to come. “When Reisner arrived at Kerma, he accidentally discovered a civilization the scope of which was unknown to the Western world,” says Berman.

In his early years at the site, Reisner focused on excavating the giant Deffufa and investigating tombs in the city’s necropolis two miles to the east. Dozens of royal tombs he uncovered there date to between 1750 and 1500 B.C., when the city was at its height. These tombs contained hundreds of human and animal sacrifices, jewelry crafted from quartz, amethyst, and gold, and preserved wooden funerary beds inlaid with scenes of African wildlife fashioned of ivory and mica. In one of the tombs Reisner unearthed a large, elegant granite statue depicting Lady Sennuwy, the wife of the prominent Egyptian governor Djefaihapi, who ruled a district north of Luxor sometime between 1971 and 1926 B.C. Nearby, Reisner found a broken bust of Djefaihapi himself.

Most artifacts Reisner excavated were distinct from what he had seen in Egypt, which led him to determine that the inhabitants of the site were from a different culture, which he named Kerma after the surrounding modern town. Reisner also recognized that different African cultures had coexisted in the ancient city. One of these he called the C-Group, a somewhat enigmatic culture that would become key to understanding the site’s origins. Despite recognizing that Kerma was populated by ancient Nubians, Reisner did not believe that the Kerma people had been capable of constructing such a magnificent site, and assumed that they had received help from the Egyptians. The Deffufa, he thought, was most likely the palace of Kerma’s Egyptian governor.

Of the thousands of artifacts that Reisner discovered at Kerma, the sculpture of Lady Sennuwy in particular cemented his Egyptocentric interpretations. “The statue was, at the time, the most beautiful Middle Kingdom statue that any American museum had ever found, and its discovery reinforced Reisner’s ideas that Kerma was ruled and influenced by Egypt,” says Berman. “Scholars at the time were completely unprepared to admit the existence of an indigenous civilization in Nubia that could rival that of Egypt.”

Bonnet’s work at Kerma quickly showed that Reisner was wrong. His team’s surveys of the city’s necropolis revealed 30,000 burials in addition to those Reisner had excavated, making it one of the largest cemeteries yet discovered in the ancient world. And after unearthing tombs, buildings, and pottery that predated the 1500 B.C. Egyptian invasion of Nubia, Bonnet realized that Kerma was not merely an Egyptian colony, but had been built and ruled by Nubians. “The country was wrongly believed to have only depended on Egypt,” says Bonnet. “I wanted to reconstruct a more accurate history of Sudan.” In addition to determining that Nubians had founded the city, the team began to identify evidence of other African cultures at Kerma. They discovered round huts, oval temples, and intricate curved-wall bastions that were distinct from both Egyptian and Nubian architecture, and instead mirrored buildings archaeologists have unearthed in southern Sudan and regions in central Africa. “We realized that the tombs, palaces, and temples stood out from Egyptian remains, and that a different tradition characterized the discoveries,” says Bonnet. “We were in another world.”

The Swiss team, now under the direction of University of Neuchatel archaeologist Matthieu Honegger, gradually started to piece together the history of that previously unknown world. They found that beginning around 3100 B.C., driven in part by an increasingly arid climate, people began to settle on the island in the Nile where Kerma would rise. These new arrivals lived in small settlements and used red brushed ceramics of a type that their descendants at Kerma would also use, and placed their huts in a distinctive semicircular pattern.

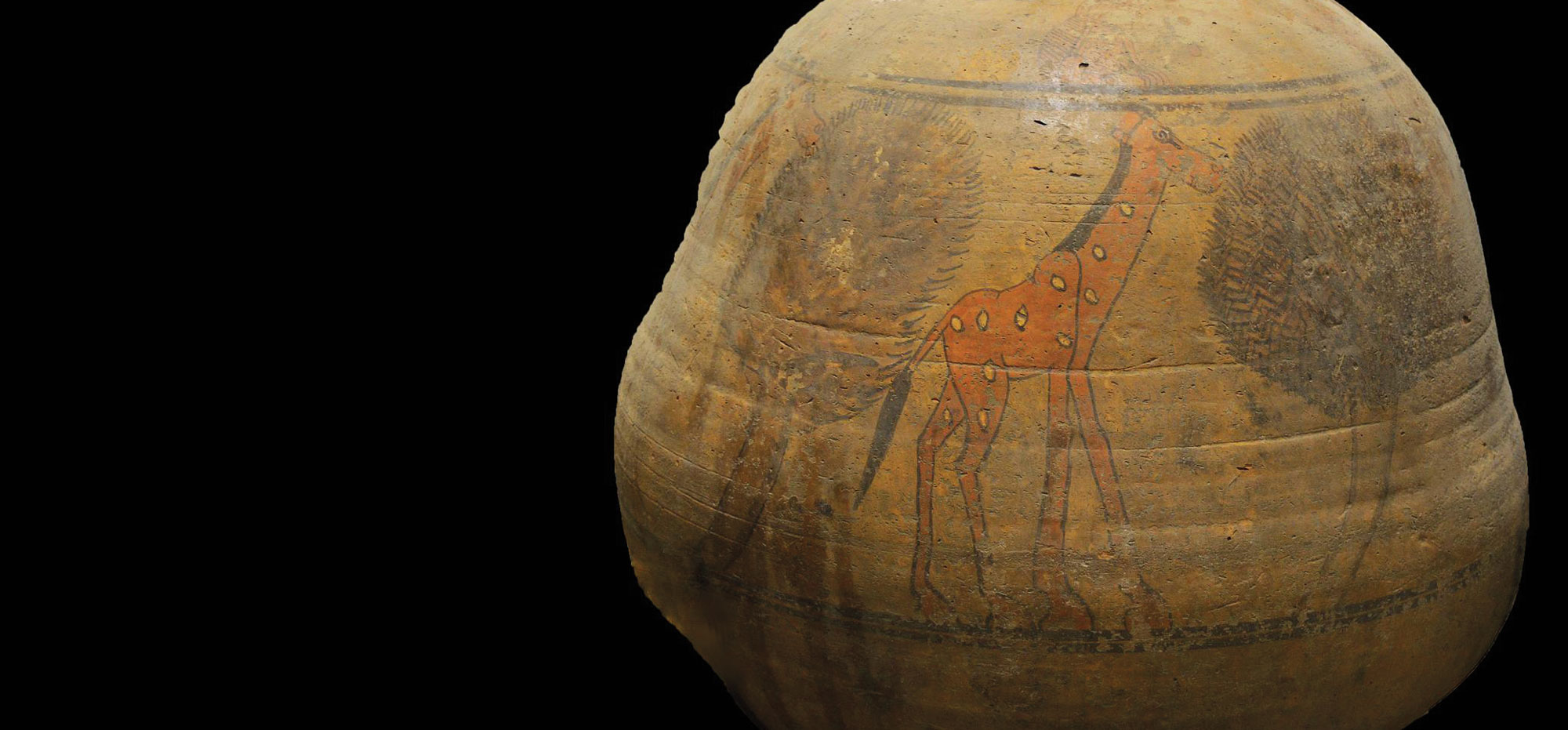

Fortifications that had been unearthed by Bonnet’s team showed that around 2500 B.C., the people of Kerma constructed a large fortress, and that a dense urban landscape quickly grew up around it. The city’s residents built circular huts, larger communal wooden structures, bakeries, and markets. Large ceramic vessels throughout Kerma seem to have provided public drinking water, likely for both citizens and visitors. A small chapel was constructed where the Deffufa would later stand, and the entrance to the city was marked by a mudbrick-and-wood gate built in a style still evident in Nubian houses today. Royal quarters with an elaborate courtyard were constructed near the city center. Around this time, nobles were first entombed in the necropolis to the east of the site. In several ceramic workshops nearby, artisans created a style of ornate dining ware only found in the nobles’ tombs. Bonnet believes these dishes were used during funeral rituals that involved meals held between mourning families and the recently deceased. The discovery of ceramic Egyptian trade seals, faience artifacts, and ivory and jewelry from southern Sudan, shows that Kerma was growing into an important trade center. Farmers contributed to the economy during this time by raising cattle and planting legumes and grain in irrigated ditches surrounding the city walls. Bonnet’s team uncovered well-preserved evidence of this in traces of wooden plowshares, holes dug in the soil for as-yet-unplanted crops, and the footprints of both people and of oxen teams, along with thousands of domesticated cattle prints pressed into the hardened mud as if they had been made only a few weeks before.

In addition to evidence of ambitious building projects and a growing economy, finds dating to early in the city’s history indicate the arrival of the C-Group identified by Reisner, possibly from Darfur in western Sudan or modern-day South Sudan. Their emergence in Nubia, marked by the sudden appearance of incised black-and-white ceramics and distinctive grave decorations, suggests that they immigrated quickly into the region. Shortly after their arrival, these new people rapidly integrated with the local Nubians and began to assimilate into the city’s culture, while maintaining a number of their own traditions.

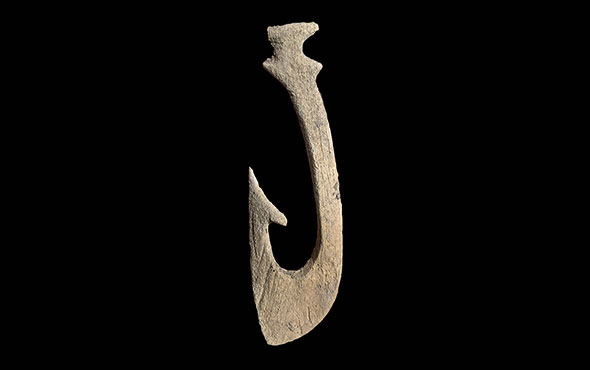

Some of the best evidence that Nubians and the people of the C-Group coexisted at Kerma has been uncovered by Honegger’s team in the necropolis. They found that graves of Kerma people from this early period were generally small pit burials in which the dead were placed in a fetal position on a mat made from either leather or woven plants. Small rows of cattle skulls were often placed in an arc outside the grave, and additional objects such as ceramic vessels, jewelry, and sacrificed animals were arranged around the body. Most men were buried with an ostrich-plume bow, and most women had a wooden staff in their graves.

Honegger’s team has also discovered that during the necropolis’ earliest phases, graves from the C-Group culture were surrounded by multiple stelas, and those of the Kerma culture were covered in a decorative pattern of black and white stones. Honegger was surprised that the style of ceramics found in the graves did not always correspond to the culture suggested by the decorations on the outside. In several instances, Honegger observed that Kerma pottery was found in graves marked by C-Group stelas, and C-Group pottery was excavated from graves marked by Kerma pebbles. For him, the mixture of funerary styles indicates that the two groups not only coexisted, but probably intermarried, and that upon their death, a person could be buried in a way that honored both traditions. Although evidence shows that the C-Group suddenly disappeared from Kerma around 2300 B.C. and moved north toward Egypt, their brief presence helped establish a multicultural foundation that would endure throughout Kerma’s history.

Some buildings Bonnet has unearthed at Kerma suggest that African influences from outside Nubia endured, and that foreign people continued to live at Kerma even after the C-Group departed. To him, the building styles there represent a conglomeration of cultures, with architecture not only influenced by Egyptian practices, but also inspired by other African traditions. In particular, a courtyard in the southern part of the city surrounded by circular structures and a small fort featuring curved defensive walls allude to African traditions that resemble modern architecture in Darfur, Ethiopia, and South Sudan. Much like the C-Group, however, the precise identity of these later African populations at Kerma remains unknown. Little archaeological research has been conducted in southern Sudan, and there are very few known sites with which to compare Kerma.

Kerma continued to thrive after the departure of the C-Group people. Bonnet and Honegger’s excavations in the necropolis show that around 2000 B.C., Kerma’s kings initiated construction of elaborate royal tombs surrounded by thousands of cattle skulls. This signaled the beginning of a new phase in the city’s history as it grew in size and its rulers began to exert their influence across northeast Africa. Bonnet’s analysis of the multiple building stages of the Deffufa shows that it was enlarged from a chapel into a multistory temple and became the city’s religious center. Cults devoted to the sun likely worshipped atop the Deffufa and those dedicated to the underworld practiced rituals in a nearby windowless chapel. Excavations throughout the city show that the number of bakeries, workshops, religious structures, courtyards, and houses increased dramatically at this time. Bonnet also discovered that there was a significant increase in the number of wealthy houses, and that the royal quarters were expanded. The construction of increasingly robust fortifications suggests there were frequent military clashes with Egypt as both powers competed for control of the Nile Valley.

Now firmly established in a fortified capital, around 1750 B.C., the kings of Kerma ordered an even more massive palace to be built. Their royal tombs also became even more lavish. At the southern end of the necropolis, Bonnet and Honegger have unearthed very large tombs, some measuring 200 feet in diameter and each containing more than 100 human sacrifices. An abundance of Egyptian artifacts and the discovery of ceramic trade seals bearing the names of Egyptian pharaohs in Kerma’s necropolis suggest that, despite their military clashes, the two powers maintained close economic connections during this time. According to contemporaneous Egyptian inscriptions, however, this relationship deteriorated for good after a failed invasion of Egypt by Kerma in 1550 B.C. Following that campaign, the Egyptians responded with a series of invasions under Thutmose I around 1500 B.C., and Thutmose II (r. ca. 1492–1479 B.C.) some 20 years later. These resulted in brief Egyptian occupations of Nubia that were subsequently rebuffed by revolts and counterattacks. In 1450 B.C., Thutmose III (r. ca. 1479–1425 B.C.) launched a final campaign into Nubia. He successfully conquered Kerma and established a firm rule over the region. Scholars had long assumed that after the Egyptians conquered Kerma they moved the capital half a mile north to the site of Dukki Gel, where Bonnet and his team have excavated in recent years. The obvious presence of Egyptian buildings at Dukki Gel from the time of Thutmose I and later had always suggested that the city was founded by Egyptians, and that it functioned as a colonial center in much the same way Reisner once assumed Kerma had.

But when Bonnet and his team began digging at the site, they unearthed fresh evidence of African architecture postdating the Egyptian invasion, a find that suggests African traditions continued at Dukki Gel perhaps after Kerma was abandoned. Even more surprising, once the team dug below the Egyptian settlement at Dukki Gel, they uncovered circular African buildings dating to before the Egyptian conquest. These buildings were defended by walls that have no known prototypes in the Nile Valley. Even though ancient cities were rarely built as close together as Kerma and Dukki Gel, for Bonnet the conclusion was inescapable—this was an urban center that dated to the same time that Kerma was at its height.

Bonnet wondered how an entire city built using non-Nubian African traditions and presumably serving a different population could have existed so close to Kerma. He notes that Egyptian sources say that their armies often contended not just with Nubians, but with coalitions of enemies to the south. Perhaps, he suggests, the kings of Kerma occasionally led a kind of federation of Nubians and Africans from farther south against Egypt. Leaders from the south may have brought their armies to Dukki Gel, which they built according to their traditions, and which might have functioned as a ceremonial and military center. Geomagnetic surveys at the site have yielded images of installations that might have been troop encampments, but these have yet to be excavated.

Kerma was only the first capital of what would become the Kingdom of Kush, a Nubian power that reigned across northeast Africa for another 1,300 years. The Kushite kings ruled from the cities of Napata and Meroe farther south. In 2003, while excavating a New Kingdom temple complex near Dukki Gel, Bonnet’s team uncovered a cache of granite statues nearby depicting prominent Kushite kings, such as the great pharaoh Taharqa, (r. ca. 690–664 B.C.) who ruled over Egypt, and one of his successors, King Anlamani (r. ca. 623–593 B.C.). Even though the cache postdates the abandonment of Kerma by 800 years, it is clear evidence that Kushite kings continued to honor the area as the royal site where their ancestors had laid the groundwork for the rise of the Nubian Kingdom.

In fact, some cultural traditions established at Kerma endured throughout the history of Kush—and much longer. Modern Nubians in Sudan still bury their dead on wooden funeral beds in the same style found in Kerma’s necropolis, and graves in the region are still marked with decorative patterns of black and white stones. Public drinking water for thirsty travelers and workers is also provided in large ceramic vessels throughout Nubia, just as it was in ancient Kerma. Archaeologist Salaheldin Ahmed, coordinator of the Qatar-Sudan Archaeological Project, points out that for modern Sudanese, Kerma continues to provide a touchstone. “Kerma culture,” he says, “represents the real roots of Sudanese identity.”

Slideshow: A New Look at Ancient Nubia

Long-term excavations at the ancient cities of Kerma and Dukki Gel in northern Sudan have shown that the people of Nubia and other regions south of Egypt were members of sophisticated cultures centuries before the pharaohs extended their rule south. All images in the slideshow are courtesy of Matt Stirn.