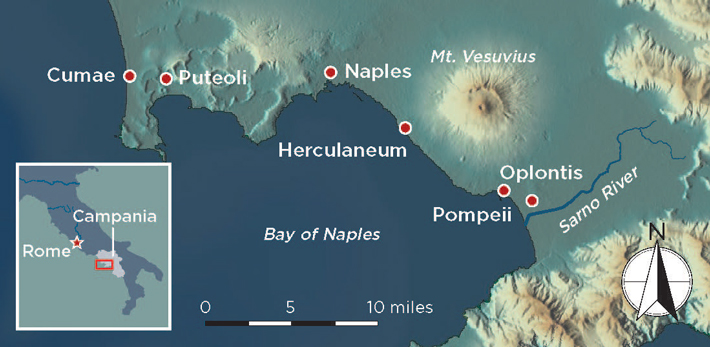

Two rooms in a vibrantly painted house were recently discovered by archaeologists in Regio V, a previously unexcavated part of ancient Pompeii.The emperor Nero is thought to have visited the southern Italian city of Pompeii in A.D. 64, perhaps spending a few nights in the enormous villa his wife, Poppaea, owned in the nearby town of Oplontis. Nero would have seen a city struggling to recover from a devastating earthquake two years earlier. “Pompeii was a city in crisis and flux,” says archaeologist Stephen Kay of the British School at Rome. The Pompeians labored to fix damaged roads, repaint walls whose frescoes had been ruined, rebuild their homes, revitalize the city’s infrastructure, repair its cemeteries, and construct what they were confident would be a new, earthquake-proof temple to their patron goddess, Venus.

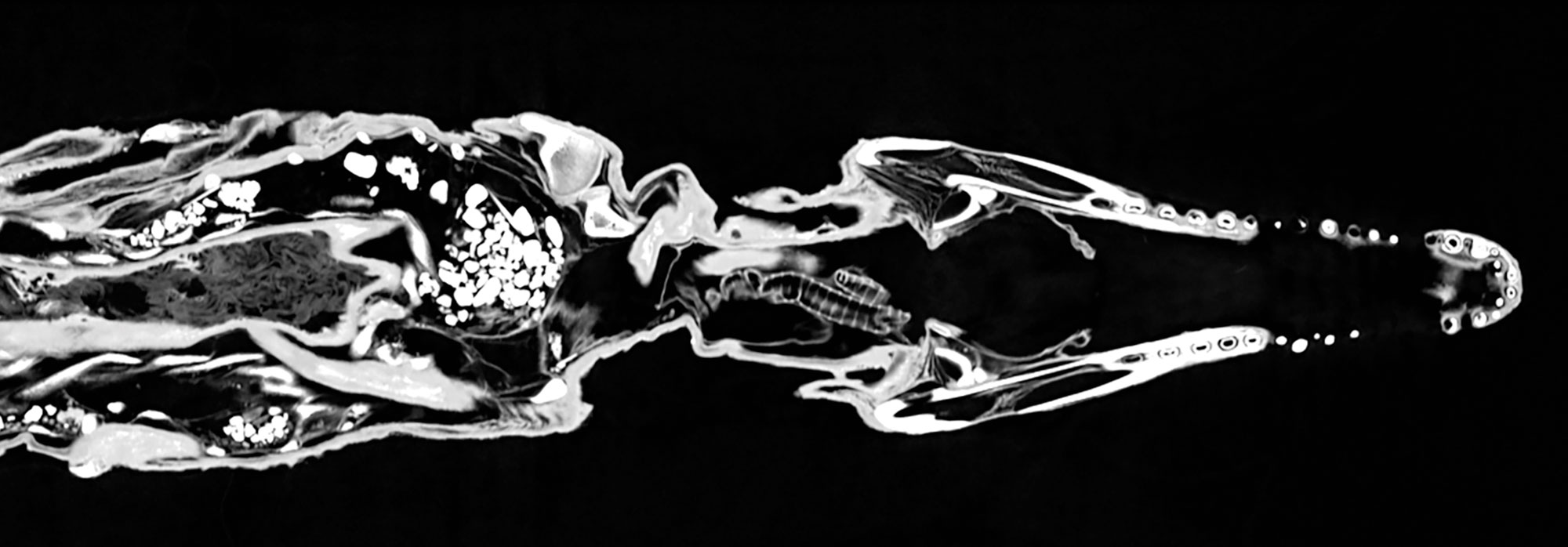

The Pompeians may not have known it, but the A.D. 62 earthquake had been a warning that the volcano looming over their city was waking up after 700 years of dormancy. In A.D. 79, Mount Vesuvius erupted in one of the largest and deadliest volcanic events in history. A dense, high-speed rush of solidified lava called lapilli, volcanic ash, and super-heated gases rushed down Vesuvius’ slopes and buried Pompeii and much of the rest of the region southeast of the mountain in as much as 20 feet of volcanic debris.

There is a tendency to think that Pompeii had always been just as it was in A.D. 79. However, by the first century A.D., it had already undergone as much as 1,000 years of change. “It’s difficult to say who the original Pompeians were,” says archaeologist Marcello Mogetta of the University of Missouri. “But if you dig below the A.D. 79 levels—which is a real challenge because you can’t destroy mosaic floors and knock down frescoed walls—you start to see that Pompeii is a site with a very long history.”

As early as the tenth century B.C., there may have been a small settlement on the site, occupied by descendants of Campania’s Neolithic inhabitants. In the eighth century, when colonists from Greece settled the region, and then in the seventh century with the arrival of the Etruscans from the area to the north between the Arno and Po Rivers, Pompeii grew larger. Before the A.D. 79 eruption, the site overlooked the Sarno River and was nearly a mile closer to the coastline. But the eruption drastically altered the landscape, cutting off access to the Sarno, an important waterway for transporting both people and the plentiful agricultural products cultivated in the area’s fertile volcanic soil, and to the busy harbor that served the city. In the sixth century B.C., a fortified wall that would define the city for the next 600 years was constructed, its shape determined by the lava flow on which Pompeii sits.

Toward the end of the fifth century B.C., Samnites migrated from the mountains of south-central Italy and took over many of the region’s Greek and Etruscan towns, including Pompeii, bringing with them new gods, customs, and building styles. “The Samnites became accustomed to urban life and, from this point on, the city was a kind of melting pot of cultures and really thrived,” says Mogetta. The Samnites remained in control of the city until the late fourth or early third century B.C., when the Romans conquered the region. Two centuries later, Pompeii’s residents felt themselves to be in a strong enough position to demand full Roman citizenship. This demand was rejected, and, in 89 B.C., the Roman general and dictator L. Cornelius Sulla took over Pompeii. In 80 B.C., the city was resettled as the Roman colony of Colonia Cornelia Veneria Pompeianorum, and Latin became the official tongue, replacing Oscan, the language of the Samnites. Pompeii continued to prosper and was a busy, cosmopolitan city of around 10,000 residents at the time of the eruption. During that catastrophe, thousands escaped their homes, but thousands of others would perish.

Pompeii lay entombed for 1,500 years, until its existence was hinted at in the late sixteenth century by small discoveries of ancient remains made by the Renaissance architect Domenico Fontana during construction of an underground water tunnel. No further work took place at the site for almost 150 years, when excavations began in earnest at the direction of Charles of Bourbon, the king of Naples. In 1763, an inscription was found confirming that the site, until then known only as La Cività, or “The City,” was in fact Roman Pompeii.

For more than two and a half centuries, with few interruptions, archaeologists have worked in Pompeii. Early on, these excavations were less scientific explorations than treasure-hunting expeditions aimed at collecting the paintings, sculptures, mosaics, jewelry, and silver that now fill many of the world’s museums. After decades of largely disorganized, poorly documented projects, Italian archaeologist Giuseppe Fiorelli became director of excavations at Pompeii in 1860. He meticulously documented and mapped the site, dividing it into the nine regions (Regio I–IX) that are still in use. Fiorelli also developed the technique of creating casts of people and animals trapped by the eruption by pouring plaster into the hollows left in the volcanic debris by decayed remains. Excavations have continued ever since, halted only by World War II—when Pompeii was bombed—and a powerful earthquake in 1980.

Despite this nearly constant collecting, surveying, mapping, and digging, as of 2018, about a third of Pompeii still had never been excavated. At this point, in Regio V, in the northern part of the city, the layers of lapilli, ash, and volcanic mud started to collapse under their own weight, imperiling excavated properties and adjacent streets. To address this, a new excavation project was begun in a previously unexplored part of Pompeii. “The conventional idea when these excavations started was that they would solve issues of damage control and conservation,” says archaeologist Steven Ellis of the University of Cincinnati. There was an expectation, he adds, that all the typical Pompeian things—wall paintings, shops, mosaics—would be found. “What they’re finding is, in some ways, much more interesting,” Ellis says. “It’s enabling us to see not just the state of the city in A.D. 79, but also what it was like when it first became an archaeological site 200 years ago. It’s a chance to see the Pompeii that the first excavators saw. We’ve never had that before.” This, he explains, is allowing archaeologists to ask questions about Pompeii that haven’t been possible for a very long time. “It’s more than just looking at how the colors of a painting have faded,” he says. “It’s ‘What were these paintings actually like when they were buried? Were amphoras really stacked against the walls the way we often see them now? Is this how the city really looked, or is what we see now a product of the past two centuries?’ If we see the site as an archaeological laboratory, Regio V is an entirely new kind of lab.”

But Regio V is not the only part of Pompeii that archaeologists are investigating. At locations across the city, in its temples, public baths, restaurants, gardens, houses, villas, and cemeteries, they are looking for elusive evidence of Pompeii’s earliest settlements, revising previously held theories about the age of the site, reexamining properties that were excavated centuries ago, and even searching for evidence of what may have become of those who survived the eruption.

-

(Courtesy Marcello Mogetta/University of Missouri)

(Courtesy Marcello Mogetta/University of Missouri) -

(© FU Berlin)

(© FU Berlin) -

(Pasquale Sorrentino)

(Pasquale Sorrentino) -

(Pasquale Sorrentino)

(Pasquale Sorrentino) -

(Pasquale Sorrentino)

(Pasquale Sorrentino) -

(© Villa Diomedes Project. 3D computer graphics: Alban-Brice Pimpaud (archeo3d.net))

(© Villa Diomedes Project. 3D computer graphics: Alban-Brice Pimpaud (archeo3d.net)) -

(Wikimedia Commons)

(Wikimedia Commons) -

(LH Images/Alamy Stock Photo)

(LH Images/Alamy Stock Photo)