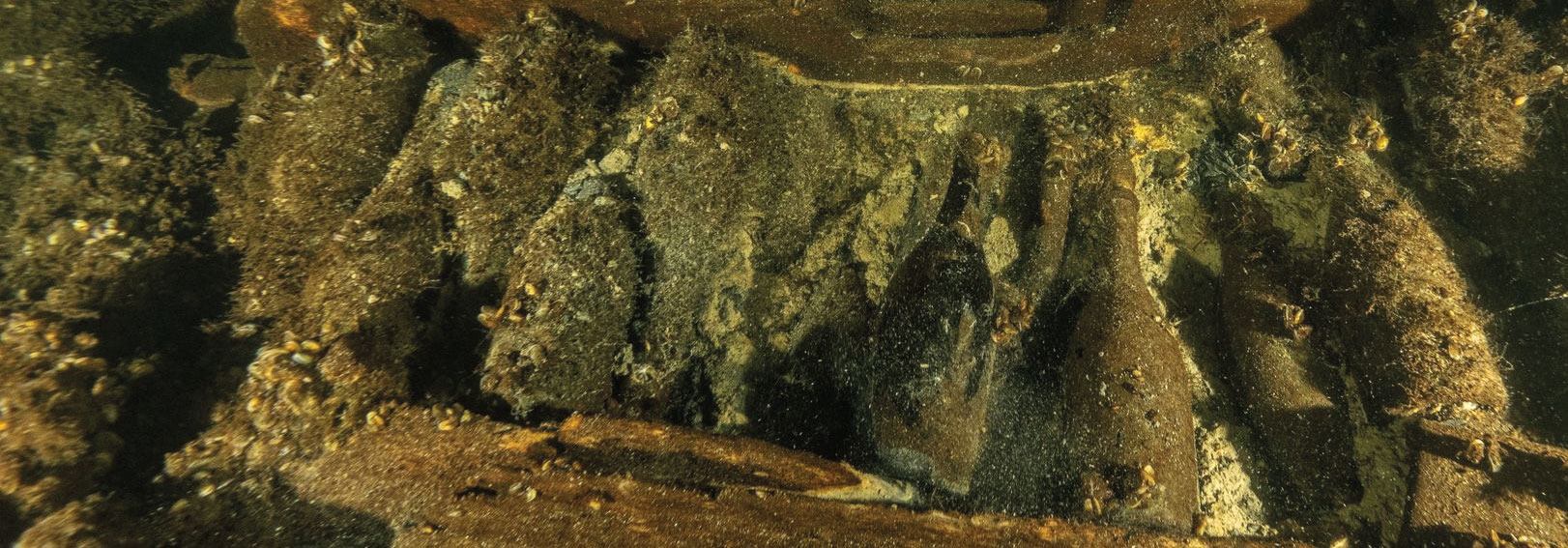

A multinational team led by the University of Oxford’s Pitt Rivers Museum is revealing a previously unknown story about elephant ecology in West Africa by analyzing ivory from a 500-year-old shipwreck discovered on Namibia’s coastline. The Portuguese vessel Bom Jesus sank in 1533 while en route to India loaded with valuable cargo that included copper from Central Europe, German faience, and more than 100 West African forest elephant tusks, the largest ivory cargo ever found in a shipwreck. Genetic analysis of the tusks showed that the elephants were from 17 distinct herds in West Africa, some from areas not traditionally associated with the ivory trade. To the team’s astonishment, four of these herds still exist today, made up of descendants of those who were hunted to fill Bom Jesus’ hull.

In addition to helping ecologists understand the history of West African elephant populations, information gained from the shipwreck is providing fresh insight into elephant behavior. While nearly all modern forest elephant herds spend their whole lives in thick jungle, likely pushed there by confrontations with humans, isotope analysis of the wreck’s ivory has demonstrated for the first time that herds in the past often thrived in open savanna as well as forested areas. “As archaeologists, we have an important role to play in sharing our data and connecting its relevance to modern people and habitats,” says project codirector Ashley Coutu of the Pitt Rivers Museum. “Archaeological data not only tells us about the long-term histories of endangered or extinct species, but also informs us about how animals and humans coexisted in the past, which is directly relevant to managing human-wildlife conflict.”