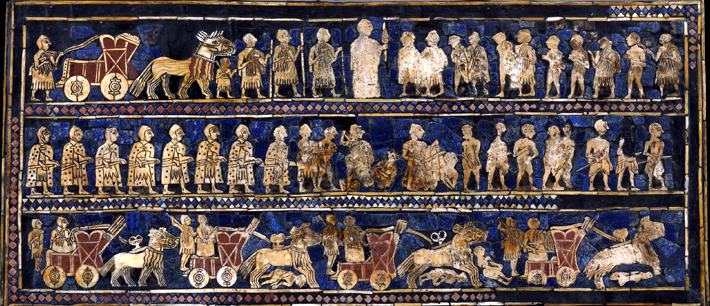

One of the most vivid glimpses into the mind of an ancient ruler was unearthed in 1928, at the royal cemetery of Ur, in modern-day Iraq. The so-called Standard of Ur, dating to around 2500 B.C., is a foot-and-a-half-long trapezoidal wooden box decorated with mosaics made of lapis lazuli, shell, and red limestone that depict a flourishing Mesopotamian city-state. On one side of the box, average citizens dutifully line up to offer produce, sheep, and other livestock as taxes to the king, who is shown with his retinue feasting on the revenues. On the opposite side, the king’s army, funded by tax levies, is seen smiting Ur’s enemies. Both scenes illustrate a king’s-eye view of a highly idealized government functioning with great efficiency thanks to what has become a universal human experience. “Everybody gets taxed,” says University of Michigan historian Irene Soto Marín, who studies taxation in Roman-era Egypt. She points out that the archaeological record is replete with documents recording the typical person’s tax burden. “Many of the texts that survive from the ancient world aren’t literary works, but mundane tax receipts,” Soto Marín says. “They’re the most direct way to get insight into the policies of ancient states and the impact those policies had on people’s daily lives.” A vast body of eclectic evidence reveals how rulers administered taxes on everything from crops to labor, how people complied with their mandate, and how taxes could contribute to the well-being of the state. But these artifacts also show that while the powerful had ambitious plans to extract revenue, at least in some cases, taxpayers themselves did not behave with the perfect compliance of the subjects depicted on the Standard of Ur.

-

(Lanmas/Alamy Stock Photo)

(Lanmas/Alamy Stock Photo) -

(Stefano Ravera/Alamy Stock Photo)

(Stefano Ravera/Alamy Stock Photo) -

-

(Photo By DEA/G. DAGLI ORTI/De Agostini via Getty Images)

(Photo By DEA/G. DAGLI ORTI/De Agostini via Getty Images) -

(Courtesy Zhenhong Yang)

(Courtesy Zhenhong Yang) -

(© The Trustees of the British Museum/Art Resource, NY)

(© The Trustees of the British Museum/Art Resource, NY) -

(History and Art Collection/Alamy Stock Photo)

(History and Art Collection/Alamy Stock Photo) -

(Album/Alamy Stock Photo)

(Album/Alamy Stock Photo)