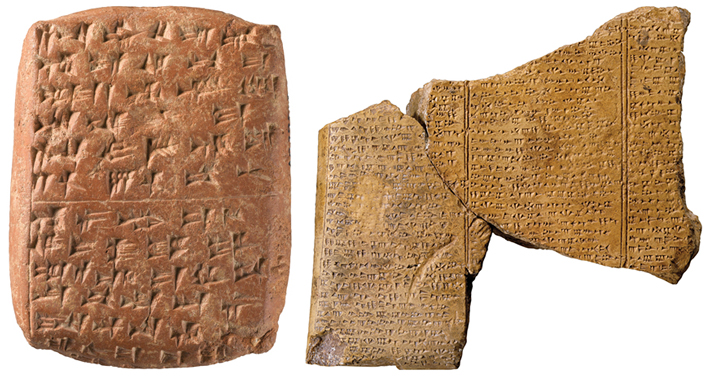

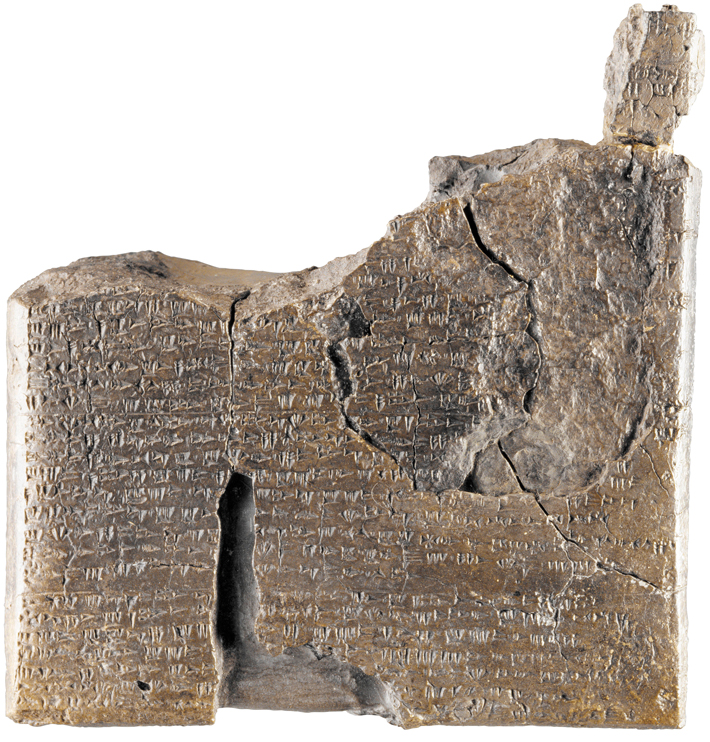

Urtenu was a Late Bronze Age merchant of some status. From his town house in Ugarit, on the coast of Syria, he ran a trading firm that conducted business on behalf of the state. Beginning sometime before 1200 B.C., he kept letters, accounting ledgers, and administrative texts documenting the export of copper ingots, wood, and other goods from the interior of Syria and the import of wares from Cyprus and Egypt. Urtenu also sent and received diplomatic letters and had an impressive list of contacts. Among the 650 baked clay tablets found in the ruins of his house thus far, archaeologists have turned up missives to and from the kings of Egypt, Assyria, Beirut, and the Hittite realm in what is now Turkey. Urtenu corresponded with these potentates in the name of the king of Ugarit. He seems to have been a cultured man, too. Archaeologists found passages from the ancient Mesopotamian poem the Epic of Gilgamesh in his house, written, like almost all surviving texts in Ugarit, on densely inscribed tablets.

Between 1200 and about 1185 B.C., Urtenu’s correspondence took on a more ominous tone. Polite requests for help turned into increasingly desperate pleas as severe drought and famine began to upend life in the kingdoms and city-states around Ugarit. The tablets speak of biru, “hunger” in the Akkadian language, which was widely spoken in the Levant, spreading across the landscape. “If there is any goodness in your heart, then send even the remainders of the [grain] staples I requested and thus save me,” pleads a Hittite official. Food shortages were becoming dire. “In the land of Ugarit there is a severe hunger. May my Lord save it, and may the king give grain to save my life…and to save the citizens of the land of Ugarit,” wrote Ugarit’s king Ammurapi (ca. 1215–1190 B.C.) to the Egyptian pharaoh Seti II, who ruled from about 1200 to 1194 B.C.

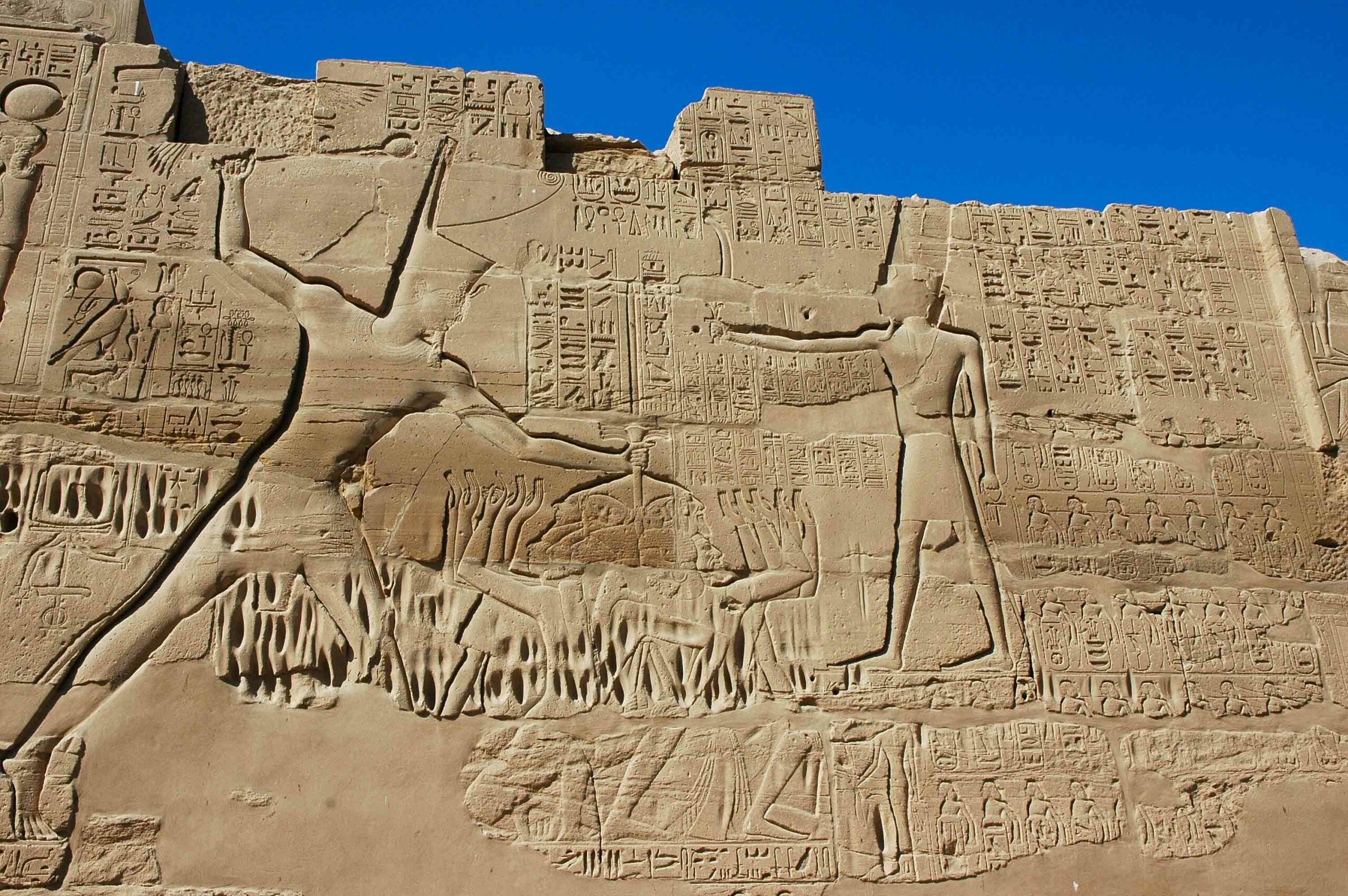

War was also coming. One letter, likely one of the archive’s last and probably never sent, speaks of invaders appearing off the coast and establishing a beachhead at Ra’su, barely five miles from Ugarit. In the letter, Ammurapi begs the viceroy of the Hittite vassal city-state of Carchemish, “Send me forces and chariots and may my lord save me from the forces of this enemy!” The enemy was almost certainly the so-called Sea Peoples, maritime marauders whose identity remains unclear and who overran Ugarit and burned it to the ground. It did not fall alone. At the same time, across the eastern Mediterranean, cities and trading networks were threatened by drought, invasion, mass migration, and possibly local insurrection. Egypt’s dynastic system survived a cataclysmic battle with the Sea Peoples in 1177 B.C., but Mycenae and Pylos in Greece, and states in Cyprus, Canaan, and Turkey were all obliterated in what scholars have termed the Late Bronze Age collapse.

The Urtenu archive, which was discovered in 1973 and is still trickling into publication, documents life in Ugarit from its moment of greatest plenty through the subsequent famine and violence that engulfed it. From the 1930s to the 1970s, archaeologists excavating the ruins of Ugarit’s royal palace, where Urtenu’s patron ruled, unearthed more than 1,000 tablets, but no archive yet discovered has the range and impact of Urtenu’s trove. “The archive allows us to see clearly what formerly we could only glimpse,” says archaeologist Yoram Cohen of Tel Aviv University. “We see how these semiofficial traders operated and how they acted as engines for the state of Ugarit. And it shows how the enemy came from the sea and destroyed the city at one go.” Like most Ugaritic scholars, Cohen has never visited the site, which was partly covered by a Syrian military base until the 1980s and which has been difficult for non- Syrian archaeologists to visit since civil war broke out in 2011. French epigraphers published translations of 130 tablets from Urtenu’s house in 2016, and Cohen believes there are perhaps as many as 100 more sitting in storerooms and museums in Syria, awaiting decipherment. Syrian archaeologist Khozama al-Bahloul, current codirector of the research project at Ugarit, says that excavation has continued uninterrupted throughout the civil war, and that the fighting has not damaged the site. Recently, she has been excavating the city’s ancient military defenses, including the fortifications and ramparts that proved unable to stop the Sea Peoples’ onslaught.

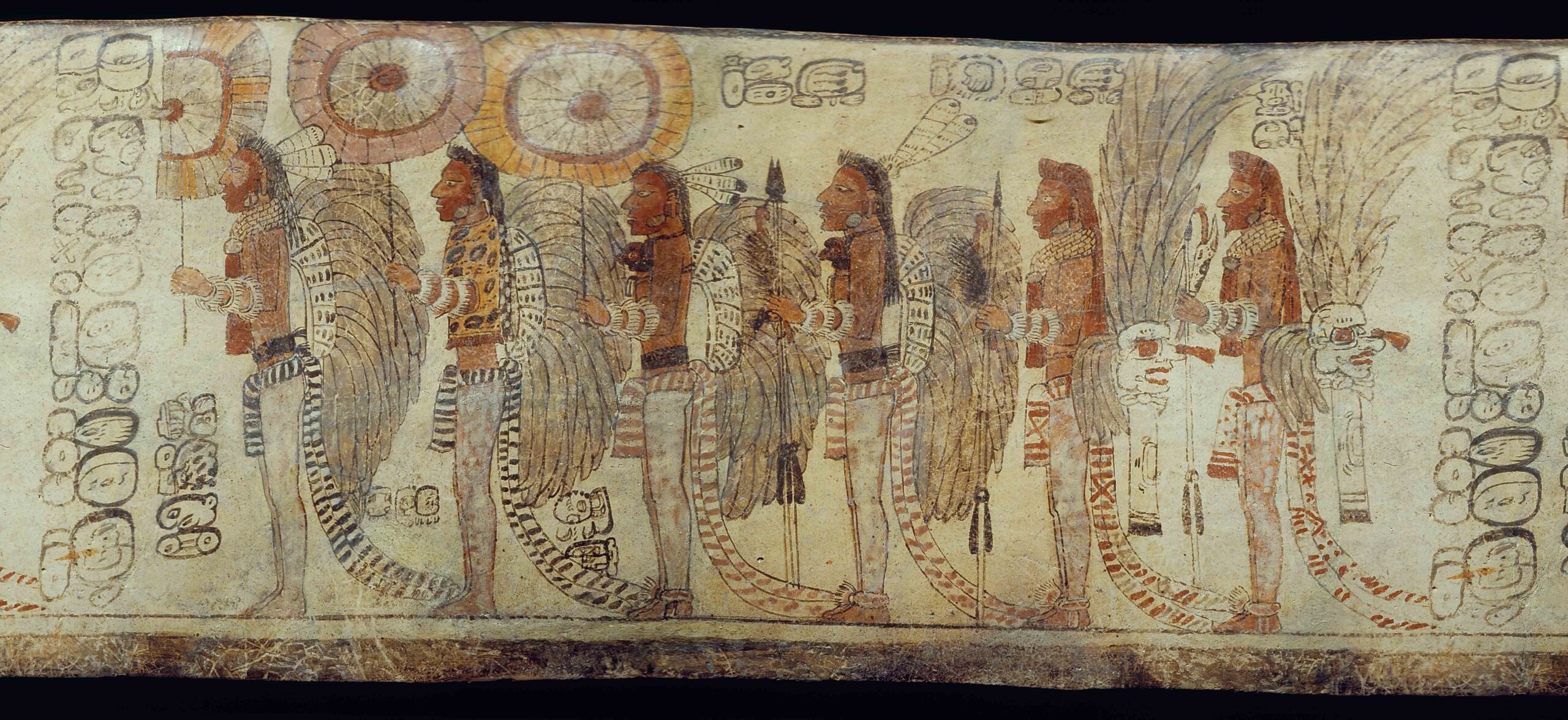

During nearly a century of excavation, archaeologists have discovered nine major tablet stores in Ugarit, some in administrative buildings, others in what were clearly private homes. The archives are spread around the city and reflect a culture of meticulous, even obsessive, record-keeping as Ugarit’s trade ties grew and flourished. The archives have also illuminated how these trade networks and writing developed side by side. Ships and donkey caravans that carried textiles or grains also carried skilled laborers, including sculptors, potters, metallurgists, and carpenters—along with scribes from Egypt and Iraq whose writing systems were among about a half dozen used in Ugarit. Sumerian cuneiform and Egyptian hieroglyphs appear in the same archives, along with a Cypro-Minoan script that modern scholars have not been able to decipher. The most common form of writing the scribes of Ugarit employed was Babylonian cuneiform, which has turned up in all the archives, even sometimes on the same tablet with other scripts.

EXPAND

Women in Ugarit

Ugarit’s culture was distinctive in ways apart from its homegrown script. Women had an unusual degree of autonomy compared to other contemporaneous cultures, and were allowed to own property, participate in rituals, and, says archaeologist Yoram Cohen of Tel Aviv University, were almost certainly trained as scribes. A census document shows women as the heads of households, listing among the residents of one neighborhood “a preeminent wife in the house of Artthb; a wife and her two sons in the house of Iwrpzn; a wife and an unmarried woman in the house of Ydrm; [and] two preeminent wives and an unmarried woman.” Ugarit’s queens were also in charge of their own estates and had prominent diplomatic roles. One queen, named Thariyelli, personally sacrificed a bull on the city’s acropolis, an honor usually reserved for men. Tablets also record the scandalous divorce of Ammistamru II (r. 1260–1235 B.C.) and his wife, a niece of the Hittite king. Ammistamru’s wife, whose name does not appear, was accused of causing him some unspecified “trouble,” banished from the city, and then ordered back to be subjected to further punishment.

In the last century before the seaborne invaders leveled the city, Ugarit’s residents made their own contribution to the list of scripts in use, adding alphabetic cuneiform, which they quickly adapted to represent their spoken language, Ugaritic. It was a unique innovation that presaged the dominance of alphabetic scripts in the centuries to come and the decline and eventual disappearance of other writing systems. “By the thirteenth century B.C., there are five writing systems and eight languages all present at the same time in this one cosmopolitan city,” says Carole Roche-Hawley of France’s National Center for Scientific Research (CNRS), who has worked extensively in Syria. “One of them is the script they invented, and they write their own spoken language, as well as all their local literature, in this new script.”

The city of Ugarit dates from the beginning of the second millennium B.C., when Amorite tribes are believed to have migrated from the arid Syrian interior into the area, where they mixed with Canaanite coastal peoples. Lacking military power but possessing a good harbor, the residents of Ugarit built up their wealth by trading wood from timber forests in coastal ranges. Tin from Afghanistan, dried fish from the Nile, Mycenaean pottery from mainland Greece, and furniture crafted from Syrian wood all passed through Ugarit’s harbor, where they were tallied up on clay tablets and then bartered at ports across the Mediterranean. By 1400 B.C., Ugarit stood at the boundary between the two superpowers of the day, Egypt and the Hittite Empire. Trade ties flourished among the eastern Mediterranean’s centralized, palace-based states, all of whom jockeyed for a strategic and commercial edge, a state of affairs that Ugarit was in prime position to take advantage of. The city’s rulers adroitly played the Egyptians and Hittites against each other. “Hittite-Egyptian relations went back and forth between friendliness and fighting throughout the Late Bronze Age,” says archaeologist Kevin McGeough of the University of Lethbridge. “Ugarit acted as a pivot both between them and between the Aegean and Mesopotamian worlds. They all interacted and came together there.”

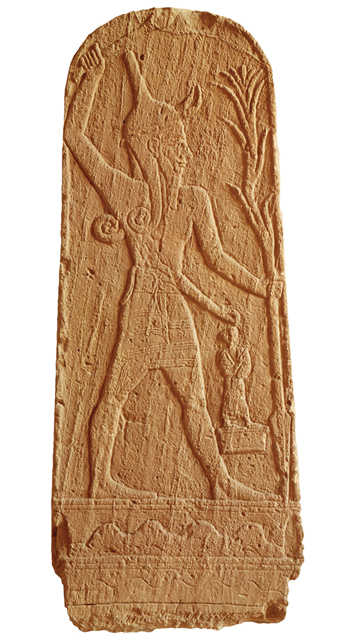

The first archaeologists at Ugarit unearthed evidence of Egyptian influence and concluded that it had been an Egyptian colony, but later research showed that all those scarabs, statuettes, and sphinxes had been found only in high-status contexts. Ugarit’s elites, it appeared, liked Egyptian-made finery. By combining the information gathered from nearly a century of archaeological research with that from the more than 5,000 tablets that have been excavated, translated, and published thus far, scholars have been able to reconstruct Ugarit’s history of Bronze Age mercantilism and power politics in close detail. People arriving by sea passed through a monumental gatehouse into the city and soon saw the city’s royal complex, spread out over more than two acres. A temple to Ugarit’s patron deity, Baal, towered 150 feet over the city, and may have also been used as a lighthouse. Inside the temple, priests ran their fingers over ivory replicas of cow livers inscribed with incantations, hoping to read the future. Almost to the end, the city’s residents remained fascinated with Egypt. A tablet dating to around 1210 B.C. records that the king of Ugarit asked the pharaoh Merneptah (r. ca. 1213–1203 B.C.) to send his artists to chisel an image of the Egyptian ruler in stone. Certainly, replied Merneptah, “as soon as they finish…fulfilling their duty to the great gods of Egypt,” by which he meant working on his own monuments. Ugarit’s upper echelons thought nothing of dividing their loyalties between Egypt, their cultural lodestar, and the Hittite Empire, to which they owed political allegiance.

Outside the royal precincts, the city was a warren of streets and alleys, some barely three feet wide, with multistory apartment blocks where neighbors shared common olive-oil presses and textile-weaving equipment. Bards recited epic poems as popular entertainment. (See “A Poem for Ugarit.”) Local craftspeople made imitation Mycenaean and Egyptian pottery for the masses, while the upper class had the real thing.

Perhaps surprisingly for such a well-connected figure, Urtenu lived in one of these out-of-the-way neighborhoods. The French and Syrian archaeologists who have excavated his house since 1986 have found that it was constructed with cobblestones instead of higher-class ashlar masonry, although it did have an ashlar floor. “Had there been no tablets, the archaeologists would have said this is a mediocre house,” says Robert Hawley, who teaches Ugaritic studies at the Practical School of Higher Studies in Paris. Scholars have puzzled over why such an ordinary dwelling was the site of so much official correspondence. The answer may be that the distinction between private and official activities was blurry, and that Urtenu’s trading firm was overseen, at least nominally, by queen Thariyelli’s son-in-law Shipti-Baal, who was a wealthy merchant. (See “Women in Ugarit.”) Tablet stores have been found in four other private homes, all dating from roughly the same period, around 1200 B.C., leading Roche-Hawley of CNRS to theorize that unsteady or untested leadership at the palace might have led courtiers to steer official business to domestic spaces. “It’s a period of transition at the end of the thirteenth century when the king dies and we have a new king—a young king—so people from the administration are taking business outside the palace,” says Roche-Hawley. “There are more letters addressed to the king at Urtenu’s house than were found at the palace. That says something.”

Urtenu’s house wasn’t only used for storing official records. It may also have functioned as a scribal school, where people learned to read and write Babylonian cuneiform and Ugarit’s own alphabetic script. Archaeologists have discovered pedagogical tablets there, with both scripts side by side, similar to those found in larger quantities elsewhere in the city. Ancient scribes used those tablets to learn the new script and, in the 1930s, archaeologists did so again to decipher Ugaritic.

The local script appears abruptly and fully formed on tablets, almost overnight in archaeological terms, says Philip Boyes, a philologist at the University of Cambridge. It probably arose from a deliberate policy of Ammistamru II’s (r. 1260–1235 B.C.) or another king in the second half of the thirteenth century, as “a top-down project imposed by fiat,” says Boyes, although he adds that the new script may have been tested on perishable materials before being etched in clay. Some scholars compare the move to Kemal Atatürk, the founder of modern Turkey, imposing the Latin alphabet on Turkey in the 1920s, or the state of Israel reviving ancient Hebrew to create a national language. Ammistamru’s motives are not as clear. Cuneiform, in which each character represents an individual word, was a flexible script that had existed, in different forms, for more than 1,000 years. It could be adapted to almost any language, including Semitic ones such as Ugaritic or Indo-European tongues such as Hittite. But with about 650 different characters, cuneiform was hard to teach, and some scholars believe Ugarit’s thriving, quasi-official merchant class wanted a simpler way in which to record transfers of goods and movements of laborers and skilled artisans.

EXPAND

A Poem for Ugarit

Of the thousands of texts from Ugarit, none shows the ancient Syrian city’s vibrant cosmopolitanism and civic spirit like the poem modern translators have called “Ritual of National Unity.” The text—fragments of which have been found inscribed in baked clay tablets using Ugarit’s own alphabetic script in six different parts of the city, suggesting it was widely known— includes specific references to nations that traded with Ugarit and whose citizens lived in the city. It decries slights against these foreigners and against the city’s most marginalized citizens.

The poem begins with an appeal to the “rectitude of the son of Ugarit”—or daughter, in some versions. It then calls for “the well-being of the foreigner…be it according to the statement of the Hittite / Be it according to the statement of the Alashian.” Hittites and Alashians were Mediterranean peoples who traded with Ugarit and are known from other texts to have had migrant communities in the city. Similar shout-outs follow for other groups, some obscure today. The poem then pays homage to “your oppressed ones [and]… your impoverished ones,” and some versions call for “the well-being of the woman.” Scholars have interpreted those lines as an expression of consciousness of class and gender rarely documented so clearly in ancient texts. The poem also includes what appear to be stage directions. “Here is the donkey!” it says, perhaps a prompt for someone to lead a donkey into view. The work was obviously meant to be performed, says Philip Boyes of the University of Cambridge.

Evidence from other tablets found in the city points to suspicion of foreigners, and “Ritual of National Unity” might have been less a celebration of diversity than a reflection of a belief that mistreatment of foreigners and the poor could bring bad consequences. “It shows social consciousness,” says Andrew Burlingame, a professor of Hebrew at Wheaton College, but also a belief that “mistreatment of an individual or group of nonlocal origin could interfere with the favor of the city’s gods.”

Alphabetic scripts had begun to be used a few centuries earlier in southern Canaan and the Sinai, but had not spread far. They were based on pictographic symbols associated with sounds. For example, a symbol that resembles a human head represented a sound like “r” because local Semitic words for head, such as rosh and ras, began with that sound. These scripts had only about 20 characters, enough to represent almost any consonant used in local languages, and were simple enough for even a child to learn. Exactly how Ugarit’s merchants came across the alphabetic concept is unknown, but with typically Ugaritic pragmatism, they used cuneiform signs as letters and created a script with 30 characters. These included written vowels, which earlier alphabetic systems lacked. “Alphabetic cuneiform could be considered the first alphabetic script to take account of vowel differences,” says Boyes. The new vowel renderings were little more than breathing marks next to consonants, “closer to syllabic signs rather than vowels per se,” he adds. But a key innovation had taken place—an alphabet that included vowels came into being, an event that Hawley calls “the alphabetic leap.”

The new script proved very popular. Scribes wrote down local myths, poems, and religious texts using it, jotted administrative records, and scratched it on everyday objects including axes, jar handles, weights, and spindle whorls, sometimes to indicate ownership, says Boyes, but other times, according to Hawley, apparently because they were practicing the new script--or reveling in it. Nearly half of all the texts from Ugarit appear in the new script, every word of them written in the city’s final century. Hawley believes that even if it started as a top-down project, Ugarit’s lettered classes took to the new script enthusiastically because it spoke to their need to affirm their identity in a globalized world. “There was an emotional attachment to this alphabet,” says Hawley. “One, it was easy to learn. Two, it was theirs. We have seals that have the word ‘seal’ inscribed on them. They’re fascinated with this local alphabet. They’re excited about it. The scholars who were training themselves to write Babylonian and Sumerian—we have the tablets with school texts that they were copying—would doodle the new alphabet in the margins.” Only a small percentage of Ugarit’s residents could read and write texts, though many more could write well enough to scribble basic records.

There are other signs, too, that Ugarit’s citizens, despite, or perhaps because of, their bustling trade ties, grew even more prickly about asserting their identity and more suspicious of foreigners in their midst during the city’s last decades. Foreign merchants, especially from Anatolia, now modern Turkey, were barred from owning property in the city or, in some cases, even overwintering there. Officials kept careful records on foreign residents, and laws restricted the amount of debt that local people could owe to foreign creditors. “They wanted foreigners coming and bringing things, but they also wanted to police how much power they had,” says McGeough. “Elders in the community didn’t like the fact that merchants from another city owned property in the community when local people were in debt.”

Yet all did not go as hoped for the kings and merchants of Ugarit, and trouble was already looming on the horizon before the appearance of the Sea Peoples. In the fourteenth century B.C., King Niqmaddu II (r. ca. 1350–1315 B.C.) had signed a treaty establishing Ugarit as a Hittite vassal city-state. He may have been bowing to the inevitable as Hittite armies gobbled up weaker states across northern Syria. But the Hittite rulers afforded Ugarit a high degree of autonomy—they allowed the city’s residents to maintain their lucrative trade ties and its rulers to continue to bring in Egyptian craftspeople and marry their children into the Egyptian royal line, as long as they sent annual tribute and soldiers to the Hittite capital of Hattusha. This had fateful consequences when the Sea Peoples invaded. “Ugarit was expected to participate in war efforts and send troops when requested by the Hittites,” says archaeologist Caroline Sauvage of Loyola Marymount College, who was last able to excavate at Ugarit in 2009. “Apparently this was the case before its destruction, and it might have left the city somewhat unprotected.”

In its final years, in the last decades of the thirteenth century B.C., the city’s population of about 10,000 seems to have increased, possibly due to drought in the surrounding farmland putting stress on food supplies and causing people to move to denser settlements. The Hittite capital in Hattusha was under assault either from foreign invaders, internal tumult, or some combination of the two, and soon Ugarit faced its own attackers. Archaeologists have found spearpoints—evidence of hand-to-hand combat— and traces of fires that burned simultaneously all over the city. At some point, the city seems to have been completely abandoned. Unlike nearly all other cities in northern Syria, which were soon reoccupied, Ugarit shows no sign of large-scale repopulation for at least three centuries. “Writing stops, everything stops, and no one comes back,” says archaeologist Eric Cline of George Washington University. “They didn’t even come back to dig up their buried hoards. Maybe they were all killed. But then, we don’t have any mass graves, and there’s no mention of them being enslaved.”

If he escaped the chaos of invasion, Urtenu does not seem to have ever returned to the ruins of his humble home. On the first floor, French archaeologists found a decorative alabaster chariot pommel, an object that signified prestige and royal favor for its owner. Urtenu never retrieved this treasured possession. The house’s second floor, where Urtenu kept his tablets on neat shelves, collapsed onto the first and both remained buried beneath rubble until archaeologists arrived in 1986. The alphabetic script that scribes had scratched into clay at Urtenu’s house seems to have died with Ugarit, Boyes says, although its use may have continued elsewhere for a time on materials that have decayed and are invisible in the archaeological record. A few centuries later, new alphabetic scripts, forerunners of our own alphabet, appeared in port cities on the coast of modern-day Lebanon controlled by the Phoenicians, who had been among Ugarit’s main trading partners. Scholars cannot draw a straight line from Ugarit to Phoenician writing, says Boyes, but “they’re siblings and very much part of the same regional network of culture and writing practices, so I’m sure they operated in an environment of mutual awareness and influence.” Alphabetic writing also took hold in the Aramaic kingdoms of northern Syria and, later, the biblical cities of Canaan. Old Mesopotamian cuneiform withered away. “Something happened between the thirteenth and the ninth centuries to make alphabetic writing catch on,” says Hawley, “but those intervening centuries are simply undocumented. Ugarit was a precursor and announced what was going to happen.”