The elegantly dressed woman ran her eye around the large, empty living room that had once been filled with richly hued silk-and-wool carpets made in Lahore, finely carved furniture, and calf leather–bound books. She thought of the large dining table set for so many parties with shiny silver goblets and blue-and-white Chinese porcelain, and she wondered what her life would be like in the future. She had spent decades in this far-off land, but it was time to leave. Her belongings had been packed in four heavy chests weeks before, sent ahead to arrive and be put away before she and her family even embarked on the ship that would bring them home. She thought about how happy and relieved she would be when she saw some of her precious personal items again. There was the red velvet purse with silver embroidery she carried to special events, the finest pair of silk stockings she owned, her ivory comb and pig-bristle brush, the little standing mirror she used to take a last look at herself each morning and evening, and two priceless dresses, one of which she treasured most of all.

Who was this woman? No one knows.

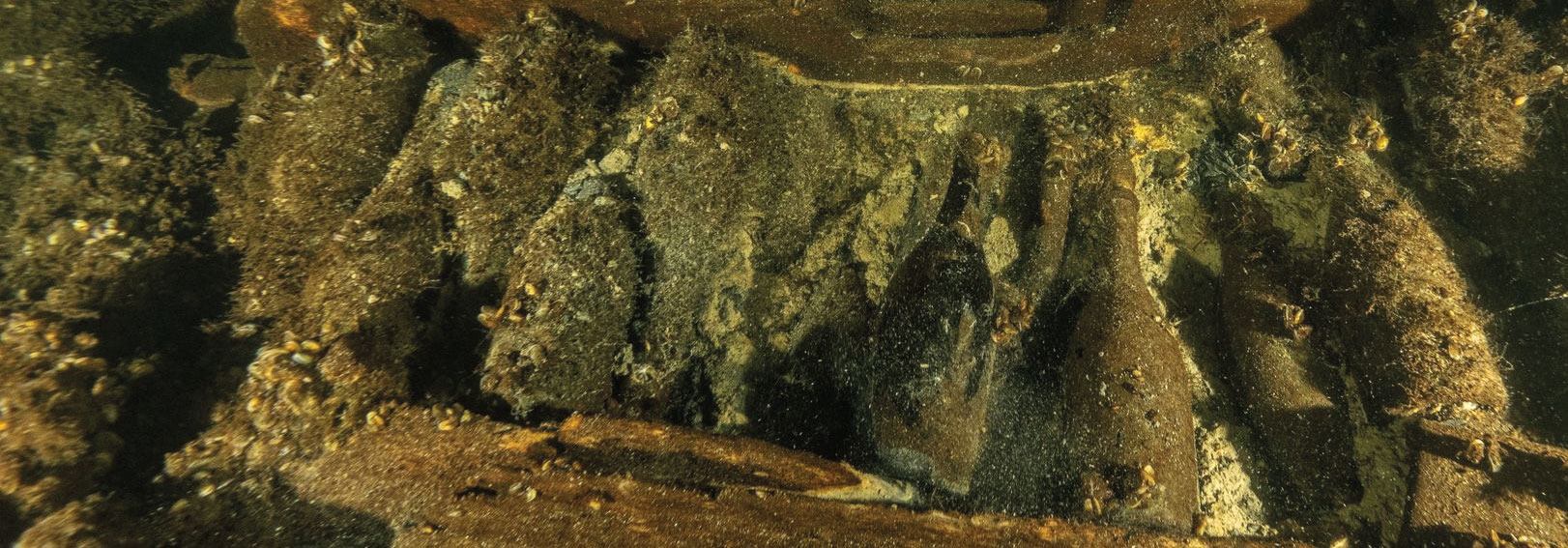

Nearly 15 years ago, off the small Dutch island of Texel in the Wadden Sea, recreational divers spotted a shipwreck 30 feet below the surface. Some five years later, the sands that covered the wreck had shifted and more of the ship began to appear. Divers quickly removed some of the ship’s contents. (For an in-depth report on the excavation, go to “Global Cargo”) The shipwreck came to be called the Palmwood Wreck for its cargo of unworked wood. As archaeologists, historians, and conservators continued to study the ship, which remains on the seafloor, and the more than 1,500 objects—including carpet fragments, wooden furniture, books, everyday and fancy dishware, and silver vessels—that were recovered, it became clear that the ship had been transporting more than just a valuable raw material used to make chess pieces and musical instruments.

EXPAND

Knit One, Purl Two

In addition to the silver and red dresses, inside one trunk recovered from the Palmwood Wreck was an extraordinary pair of patterned silk stockings. These garments afforded researchers an unprecedented look at the skill of seventeenth-century knitters and a chance for an unusual experimental archaeology project that curator Alec Ewing of the Museum Kaap Skil says was much more fruitful than he expected. One of the scholars working on the artifacts from the wreck asked volunteers from across the Netherlands to try to re-create the stockings. “The stockings look brand new,” says Emmy de Groot, textile conservator and lecturer in textile conservation at the University of Amsterdam. “By re-creating them, you can discover how they were made—and the kinds of difficulties encountered in doing so.” For example, the researchers learned that it was simple enough to knit a similar pair of stockings using wool that would have been suitable for everyday wear. However, once the volunteers started to use the type of very fine silk yarn that would have been imported from the Far East in the seventeenth-century, it became clear that it would have taken hundreds of hours to make the single pair. The researchers also had to figure out whether it was necessary to degum the silk—a process used to remove the gelatinous protein sericin to improve the material’s color, texture, and sheen—before or after knitting the stockings. This step requires submerging the yarn or the finished product in very hot water, thus shrinking it. Would the stockings still fit?

Despite their enthusiastic attempts, almost all the volunteers were unable to make a stocking matching the quality of those retrieved from the shipwreck. A few of the volunteers did, however, produce whole stockings that Ewing says would not look out of place next to the originals, although they found it an exhausting and highly complex operation. “We wear socks every day and think nothing of it,” he says. “But these stockings are so fancy. It defies imagination to think that you could have something on your feet worth thousands of dollars in labor hours—who does that anymore?"

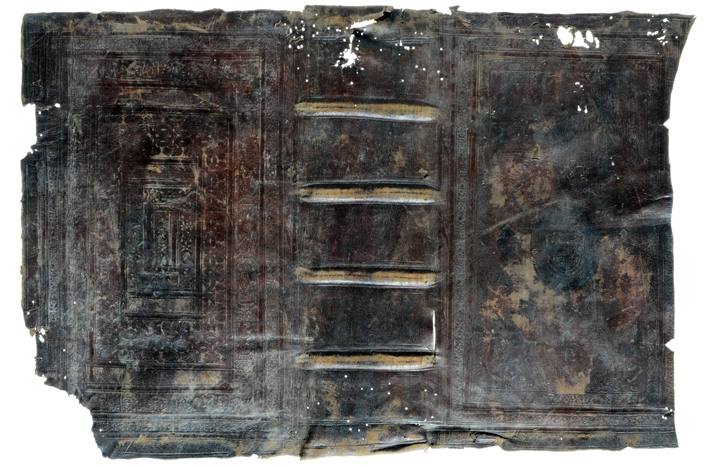

Among the contents of one trunk was a collection of textiles and garments, some of the rarest artifacts dating to the seventeenth century ever recovered. “When I was first invited to look at a seventeenth-century dress from a shipwreck, I didn’t really believe it,” says Emmy de Groot, a textile conservator and lecturer in textile conservation at the University of Amsterdam. “There was a huge number of textiles, and not just one, but, we eventually learned, two dresses.” The first was a red dress of patterned satin embellished with silver thread along its edges and seams. It had, surprisingly, retained its shape after nearly four centuries under the sea. The second, even more lavish garment, took shape over several years. “At first we didn’t immediately recognize it as a dress,” says de Groot. “When we started sorting through the over one hundred pieces of textile, some of which were quite small, we slowly started to realize that there were fragments that appeared similar, that these pieces would make another dress. It didn’t look very nice because the sewing had come apart and the fabric appeared gray, brown, and stained.”

When it was pieced together, the dress was even more exceptional than the researchers had imagined. Upon examining the pale silk under a microscope, de Groot’s students learned that tiny strips of silver had been woven into the fabric to create the silk’s interlocking braided heart pattern. “When you use your imagination,” says de Groot, “you can see how truly spectacular the dress must have been.” The garment could only have belonged to an extremely wealthy woman at the highest echelons of society and been intended for only the most special occasion. “Such an extravagant gown would have been worn on the most important days of your social calendar, like a coronation or a day at court,” Ewing says. But the dress may have been made for an even more unique, and more personal, event. “The textile researchers think it was likely a wedding dress,” he says. “And if you save just one dress, it is your wedding dress.”

For 350 years, the dress had been on the bottom of the sea in a dark and oxygen-free environment covered with the tremendous pressure of many feet of water and sand. “As soon it was brought to the surface, we were worried it would begin to change radically,” de Groot says. “I’m convinced that we started to lose silver while bringing it up through the sea. And some of the smaller fragments that were salvaged did in fact turn to dust. We were very worried and thought it—and the rest of the textiles—might degrade very rapidly and be gone in a year.” The silver wedding dress, along with the red dress, stockings (see “Knit One, Purl Two”), and other textiles from the trunk, including a red caftan that researchers have identified as originating in the Ottoman Empire, are now displayed in pressurized-nitrogen cases. Thanks to these new cases, which provide an oxygen-free environment, scholars believe the degradation will be slowed as much as is possible. “We get sensor readings from the cases in our email every day,” Ewing says, “and I can confirm that they are operating very well.”

Although some questions about the Palmwood Wreck now have answers, the mystery of who owned the trunks and their contents persists. Researchers have not been able to identify the ship by name or find documentation of a family or noblewoman whose luggage was lost. “There are records of things like this because these ships and their contents were insured,” Ewing says. “These records often survive because people make claims, but we haven’t found any records for this cargo or for a family on such a journey in the archives.” Nevertheless, according to Ewing, the wedding dress holds at least a possible clue to the woman’s identity. “When we really tried to understand what the dress would have been like, it was mesmerizing and so extravagantly expensive that it changed our understanding of this whole collection,” he says. “Who owns a dress like this?”

The dresses and other textiles have made that query even more complex because they were already 30 or 40 years old when the ship sank. “It says something that these people kept chests full of garments of all different sizes and from different cultures—some Ottoman, some from Amsterdam or London,” Ewing says. Scholars believe that they likely belonged to the wife of a Dutch consul, diplomat, or representative of a merchant family in, for example, southern Turkey, who spent years living there before returning to Amsterdam. Yet even without a face or name for the woman who got married in the silver dress, Ewing says it’s possible to understand something about her. His other favorite object from the wreck is the table mirror that must have once sat on the woman’s vanity. “I love that artifact because I can picture sitting in front of that mirror and seeing the image of that 400-year-old missing lady like I am peeking over her shoulder,” he says. “Although the glass is corroded and doesn’t reflect clearly anymore, she’s so close.”

Slideshow: Lost and Found At Sea

This is an assortment of artifacts retrieved from the wreck of a seventeenth-century Dutch merchant ship that was discovered in the Wadden Sea off the small island of Texel. Credit for all photos is Courtesy Museum Kaap Skil.