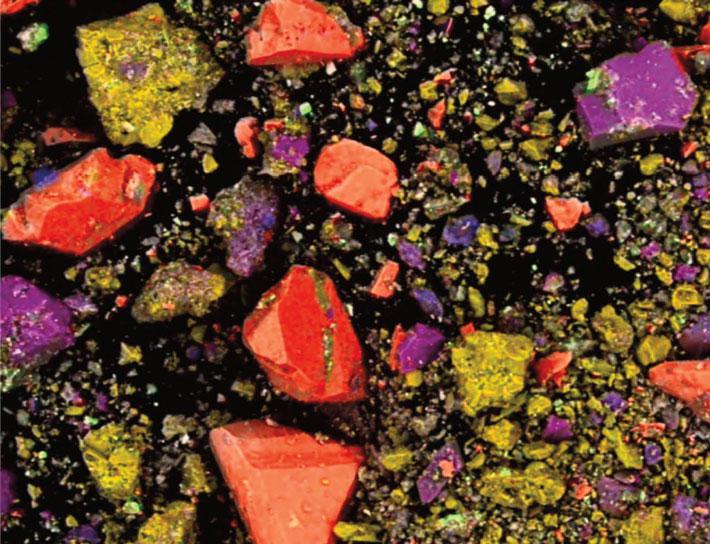

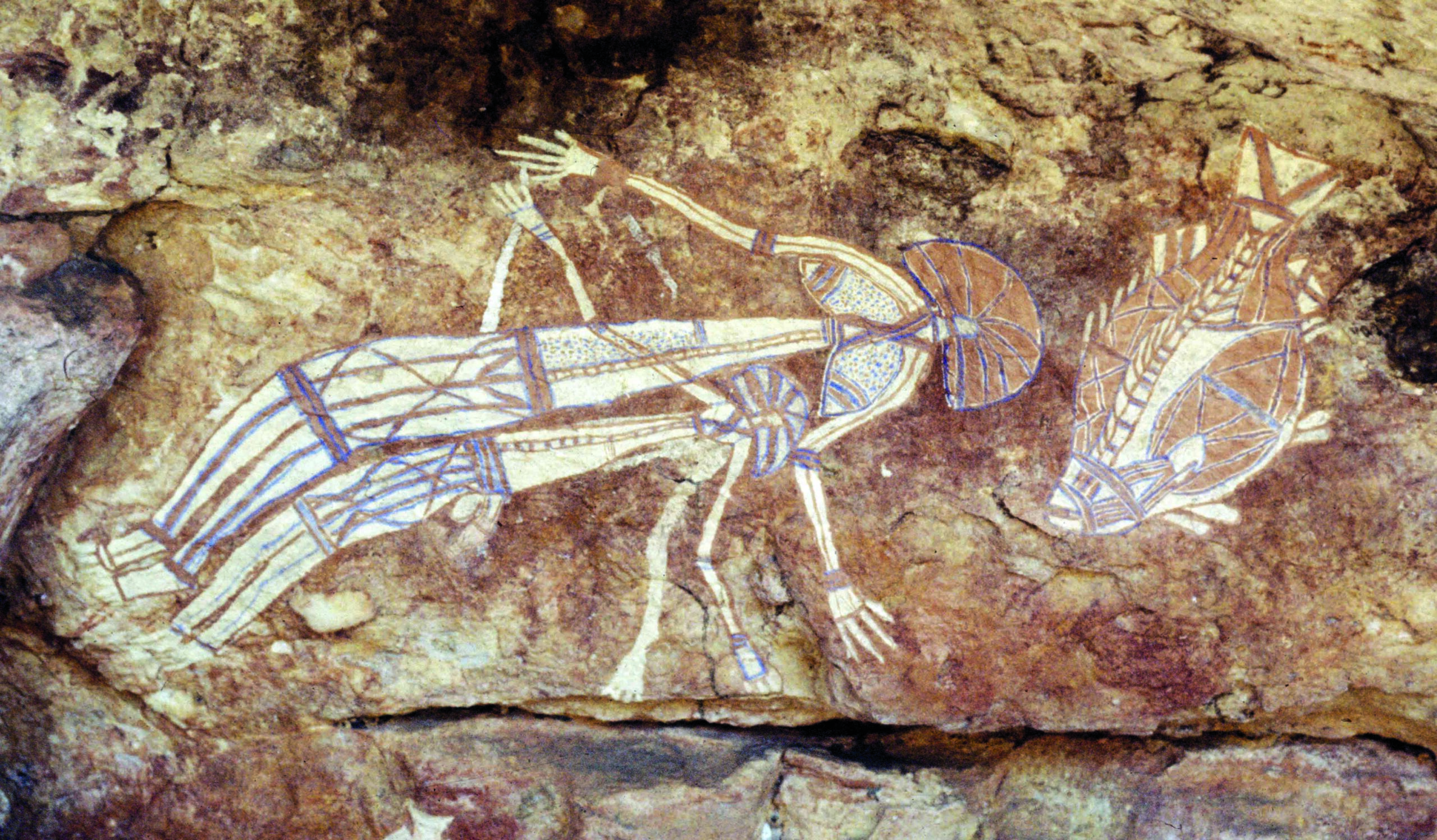

Egyptian blue is known as the world’s oldest artificial pigment, first used more than 4,500 years ago, found on wall paintings at Luxor and sculptures recovered from the Parthenon. The hue comes from a compound called calcium copper tetrasilicate. Over the past decade, museum conservators and archaeologists have taken advantage of its properties to spot the presence of Egyptian blue on antiquities: When red light is shone on the pigment, it reflects infrared light, which can be detected via night-vision goggles or cameras.

Chemists at the University of Georgia (UGA) have now determined that the luminescent quality of calcium copper tetrasilicate is retained even when the compound is reduced to what are termed “nanosheets,” a thousand times thinner than a human hair. “Even if you have a single layer, the thinnest possible, you still get the effect,” explains UGA’s Tina Salguero. At that scale, she believes, you can start thinking about modern applications.

Salguero says that Egyptian blue’s primary molecule could be incorporated into a dye to improve medical imaging, since the infrared radiation it would reflect can pass through human tissue. The pigment’s luminescent quality could also be effective for developing new types of security ink, typically used to secure currencies and other official documents from forgery. Further, the possibilities for a second act for the long-out-of-use coloring extend to devices such as light-emitting diodes and optical fibers, both of which transmit signals using the relatively long wavelength of infrared light.

The UGA team is now looking at another compound, barium copper tetrasilicate, which was also used as an ancient pigment, in this case by the Chinese.