Few monuments that survive from antiquity better represent Roman pragmatism, ingenuity, and the desire to impress than the aqueducts built to fulfill the Romans' seemingly unslakable need for water. Around the turn of the second century A.D., the emperor Trajan began construction on a new aqueduct for the city of Rome. At the time, demands on the city's water supply were enormous. In addition to satisfying the utilitarian needs of Rome's one million inhabitants, as well as that of wealthy residents in their rural and suburban villas, water fed impressive public baths and monumental fountains throughout the city. Although the system was already sufficient, the desire to build aqueducts was often more a matter of ideology than absolute need.

Whether responding to genuine necessity or not, a new aqueduct itself was a statement of a city's power, grandeur, and influence in an age when such things mattered greatly. Its creation also glorified its sponsor. Trajan—provoked, in part, by the unfinished projects of his grandiose predecessor, Domitian—seized the opportunity to build his own monumental legacy in the capital: the Aqua Traiana ("Aqueduct of Trajan" in Latin). The aqueduct further burnished the emperor's image by bringing a huge volume of water to two of his other massive projects—the Baths of Trajan, overlooking the Colosseum, and the Naumachia of Trajan, a vast open basin in the Vatican plain surrounded by spectator seating for staged naval battles.

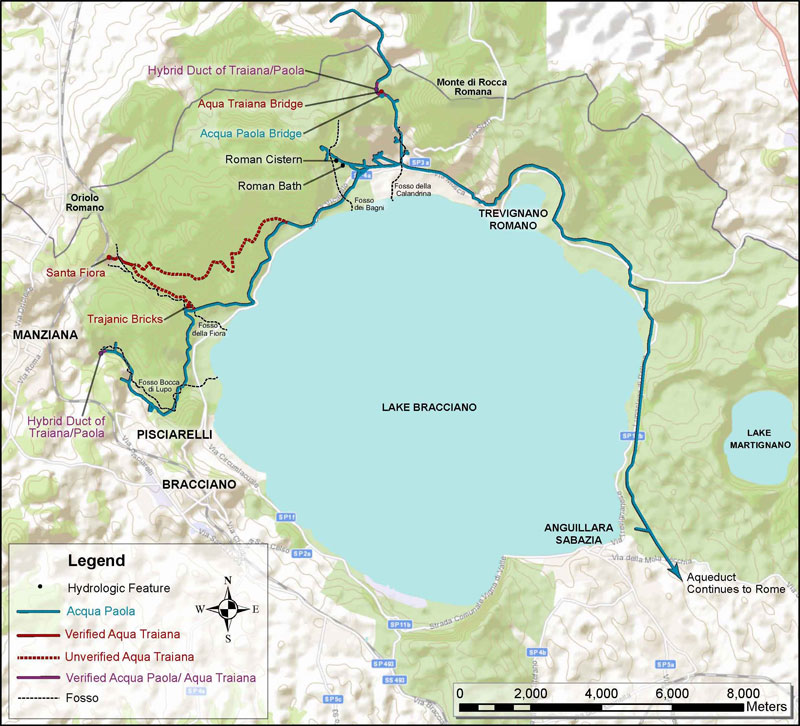

Upon its completion, the Aqua Traiana was one of the 11 aqueducts that, by the end of the emperor's reign, carried hundreds of millions of gallons of water a day. It was also one of the largest of the aqueducts that sustained the ancient city between 312 B.C., when Rome received its first one, and A.D. 537, when the Goths besieged the city and reportedly cut every conduit outside the city walls. At the time of its dedication in A.D. 109, the Aqua Traiana ran for more than 25 miles, beginning at a cluster of springs on the northwestern side of Lake Bracciano before heading southeast to Rome. However, for all the aqueduct's importance to the city, its sources and the architecture that marked them have eluded archaeologists despite centuries of searching. Now, thanks to an unusual set of circumstances that preserved them, the Aqua Traiana's sources are being brought to light at last. And for the first time, a well-preserved, monumentalized aqueduct source associated with a Roman aqueduct

has been identified.

(© The Trustees of the British Museum)

In 2008, documentary filmmakers Ted and Mike O'Neill began a project to reinvestigate Rome's aqueducts. The O'Neills started to review the existing scholarship on the aqueducts and their sources. To these self-described "archive rats," the results weren't at all satisfying. Scholars had repeatedly ignored or misinterpreted valuable evidence from descriptive documents dating from the seventeenth through nineteenth centuries—for example, Carlo Fea's History of the Waters of Rome of 1832. Soon, the Aqua Traiana became the focus of their research, since they knew it had enjoyed an extensive revival centuries after its construction. During the Middle Ages, the aqueduct had fallen into ruin. In the early 1600s, Pope Paul V—an ambitious builder much like Trajan some 1,500 years before him—undertook construction of a massive new aqueduct. At that time, some standing remains of the Aqua Traiana were probably still visible here and there in the countryside. Many of the original springs were still flowing. And it may have been possible to locate buried sections of the aqueduct by following its path underground.

The pope tasked his engineers with locating the still-flowing springs, buying the land on which they were located, and connecting them to the planned aqueduct. Once again, waters were brought to Rome from the slopes above Lake Bracciano, this time under the name Acqua Paola ("Paul's Waters" in Italian). Despite the pope's public assertion that he had relied on the sources and remains of an ancient aqueduct to build the Acqua Paola, nobody had ever been able to verify this claim, much less associate the remains of the Renaissance aqueduct with those of any ancient aqueduct.

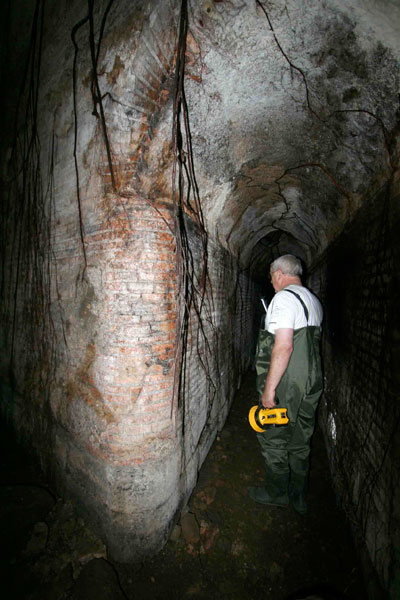

Several above- and belowground sections of the Aqua Traiana are known today, but few of them were directly incorporated into the pope's aqueduct. These ancient remains were built in a style characteristic of the second century A.D., with concrete walls faced with either brickwork or opus reticulatum—stone squares set in a precise diagonal grid. Both above- and belowground, the water channel was vaulted with plain concrete and lined below the vault with opus signinum, a cement that the Romans had used for centuries to waterproof floors, cisterns, and aqueducts. By contrast, the parts of the Acqua Paola still flowing today show no evidence of ancient masonry. In fact, a coating of modern cement entirely obscures what may lie in the walls underneath. The best evidence for the marriage of old and new is in the "dead" sectors of the Acqua Paola, remote branches that no longer contain water and have been mostly ignored by scholars looking for evidence of the Aqua Traiana's sources. In the nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries, the landscape around Lake Bracciano consisted of more open pasturage than today's dense thickets that cover fiercely guarded private lands on the lake's slopes. But even then, sustained searches yielded few traces of the older aqueduct. As recently as the 1970s, archaeologists from the British School at Rome conducted an intensive survey of the area. They were able to document previously unknown fragments of the aqueduct, yet they found no structures that could be identified as marking a source.

After months of searching through archives, the O'Neills realized that scholars had been missing important clues that could lead to sources of the Aqua Traiana and perhaps even to some ancient Roman architecture signaling their presence. Although the post-Roman names of three springs—Matrice, Carestia, and Fiora, near the town of Manziana, on the west side of Lake Bracciano—appear in reports written by the Acqua Paola's engineers, it was always thought that none of these springs had ever contributed to that aqueduct. The Santa Fiora spring had been in constant use for decades by the Orsini family, the dominant local landowners, to power their profitable lakeside mills. But the O'Neills wondered if any of the three had also supplied the Aqua Traiana almost 1,500 years earlier. A few antiquarians in the 1700s and 1800s had claimed as much, but they had said little to help later scholars identify the sources.

While a spring named "Matrice" exists today, it has clearly been in use since pre- Roman times. The spring emerges from an Etruscan irrigation tunnel called a cuniculus, which dates to the sixth or fifth century B.C., but it bears no visible evidence of Roman remains. Because the name "Carestia" is unknown in the region today, the O'Neills focused on the Fiora as the possible source of the Aqua Traiana. They knew that Pope Paul's engineers, Luigi Bernini and Carlo Fontana, had measured the flow of the Fiora's water in the seventeenth century, and it had been the most copious of all the springs in the region at that time. After a quick glance at some maps, including the most recent ones, they noticed a spot labeled "Santa Fiora." To the O'Neills' surprise, however, they could not initally find any detailed description of this place anywhere, whether in modern or older documents, so they resolved to find it for themselves.

Late in 2008, with the assistance of local officials, the O'Neills gained entrance to the site called Santa Fiora, which lies on a small farm at Manziana. What they saw, hidden within a dense stand of trees, astonished them. Under a huge overhanging fig tree, an almost perfectly preserved artificial grotto peered out from the hillside. Just up the hill, they saw traces of a structure that had once stood directly over it. Subsequent visits to the archives would reveal that this was a thirteenth-century church called Santa Fiora, dedicated to the Madonna of the Flower. Although the church had a long, well-documented history, it is almost unknown to scholars. Church records appear in the archives of the Orsini family, the local bishopric, and the hospital of Santo Spirito in Saxia at Rome, which controlled the property from as early as 1238. These documents contain a wealth of information about the church—that it was a hermitage, for example, and that it possessed a miracle-working portrait of the Virgin Mary. To judge from ledges for lamps hacked into the walls, it would seem that the hermits actually lived in the grotto itself.

EXPAND

How a Roman Aqueduct Works

Ancient aqueducts were essentially man-made streams conducting water downhill from the natural sources to the destination. To tap water from a river, often a dam and reservoir were constructed to create an intake for the aqueduct that would not run dry during periods of low water. To capture water from springs, catch basins or springhouses could be built at the points where the water issued from the ground or just below them, connected by short feeder tunnels. Having flowed or filtered into the springhouse from uphill, the water then entered the aqueduct conduit. Scattered springs would require several branch conduits feeding into a main channel.

If water was brought in from some distance, then care was taken in surveying the territory over which the aqueduct would run to ensure that it would flow at an acceptable gradient for the entire distance. If the water ran at too steep an angle, it would damage the channel over time by scouring action and possibly arrive too low at its destination. If it ran too shallow, then it would stagnate. Roman aqueducts typically tapped springs in hilly regions to ensure a sufficient fall in elevation over the necessary distance. The terrain and the decisions of the engineers determined this distance. Generally, the conduit stayed close to the surface, following the contours of the land, grading slightly downhill along the way. At times, it may have traversed an obstacle, such as a ridge or a valley. If it encountered a ridge, then tunneling was required. If it hit a valley, a bridge would be built, or sometimes a pressurized pipe system, known as an inverted siphon, was installed. Along its path, the vault of the conduit was pierced periodically by vertical manhole shafts to facilitate construction and maintenance.

Upon arrival at the city's outskirts, the water reached a large distribution tank called the main castellum. From here, smaller branch conduits ran to various districts in the city, where they met lower secondary castella. These branched again, often with pipes rather than masonry channels, supplying water under pressure to local features, such as fountains, houses, and baths.

Although only the central chamber opens to the exterior, the grotto is divided into three side-by-side chambers of different sizes and shapes, each having its own vault and light shaft. Originally, broad archways pierced the walls dividing the chambers. With the exception of a neatly preserved stone arch across the front of the grotto, almost the entire structure was made of ancient Roman concrete, brick, and mortar. Traces of the original sky-blue fresco also remained on the vaults. A niche centered in the back wall of the middle chamber would have once held a standing statue. It was the focal point of the entire original space and was clearly intended to inspire reverence in the visitor. Although the identity of the statue, which does not survive, is unknown, the likeliest candidates are either Trajan or the resident nymph representing the local waters.

On the wall directly above the niche is a Renaissance-era stucco frame bearing the Orsini family symbol, a five-petaled flower. The correspondence to the name Santa Fiora may be coincidental because the church predates the presence of the Orsini in this area, but the family would have made the most of it. In fact, this frame probably enclosed a frescoed image of the Madonna della Fiora, the wonder-working portrait of the Virgin mentioned in parish records. These records report that the fresco was gradually destroyed

by humidity.

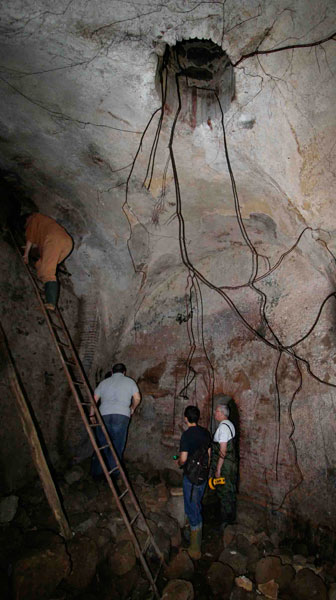

A surprise also lay in the third right-hand chamber, which can be entered through a small rectangular door just below the crown of the right arch. On the other side of the door, the floor falls away to its original level, revealing a pristine Roman springhouse. The room's concrete vault also preserves traces of the original blue fresco, along with a cylindrical light shaft at the center, creating an impressive space that could have been seen from the central chamber. Some distance along the downhill tunnel, the brickwork changes to opus reticulatum, the Aqua Traiana's signature diagonal grid pattern of masonry. At this point, the thick waterproof opus signinum lining also begins. At the juncture of these two points, a large vertical manhole shaft, now blocked far above, penetrates the tunnel's barrel vault. According to the landowners, this sector of ancient aqueduct was still serving Manziana until 1984—yet it has remained effectively unknown to archaeologists.

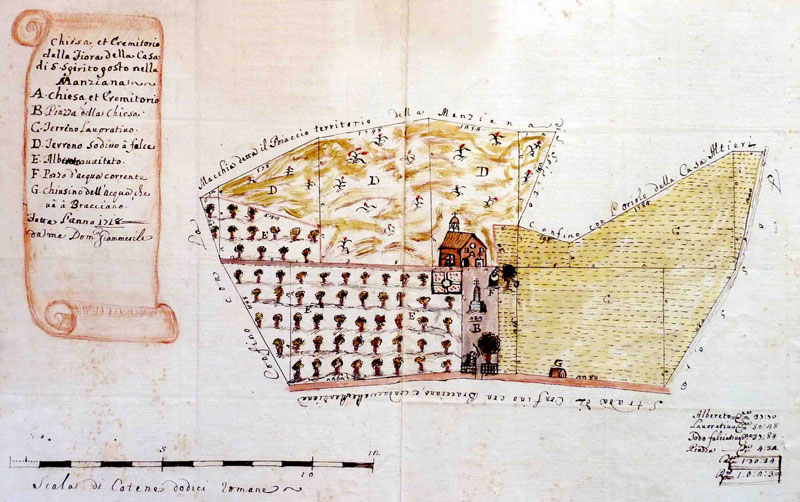

A 1718 map in the state archives at Rome represents Santa Fiora as a modest church with cropland, an orchard, a courtyard, a well with a water-lifting device in an adjacent tree, and a tiny hut near the access road. But not everything is quite as it may seem on the map. The well, which is labeled "well of running water," must be the large manhole that penetrated the aqueduct tunnel, with its water source being the aqueduct itself. Today, the sturdy masonry hut, whose label reads "hatch for water going to Bracciano," is still in place near the road fronting the property. Inside the hut, a stairway leads down to the junction of the Aqua Traiana and a modern conduit, perhaps dating to the eighteenth century, that was built for the town of Bracciano. This conduit originates at another nearby spring. For all his power, the pope could not convince the Orisini family to hand over the Fiora.

In the summer of 2010, the team focused on identifying the lost source called "Carestia," said to be near the church of Santa Maria della Fiora. A 1716 map from the Orsini Archives at the University of California, Los Angeles, had provided an essential clue to its location—an isolated aqueduct section, drawn northeast of the church, labeled "channel that captured the lost waters called the Carestia, and that conducted them to the Fiora." Now knowing to search in the dense forestland to the northeast, the team soon identified another artificial Roman grotto that is nearly the Santa Fiora's equal in size and architectural conception. Here, the vaulted ceiling has split, its cylindrical light shaft neatly sheared in half. The top of a central statue niche peeks out above the forest floor.

Most recently, the team's objective has shifted to the "dead" branches of the Acqua Paola—those that have fallen into disrepair because they are too remote to maintain. Since these dead sections are dry and sometimes even broken, they can reveal more about their construction history than the living branches, as they can be examined in cross-section. The team can even crawl along the channels to look for ancient masonry. It has become clear that little of the Acqua Paola's conduit in these areas was built from scratch. Instead, the aqueduct was a hybrid that sat directly on the remains of the Aqua Traiana wherever possible. In the southernmost branch of the Acqua Paola, on a farmstead at Pisciarelli (the colorful appellation for regions that "piss forth" water), the team found indisputable evidence that the Aqua Traiana had already been there 15 centuries earlier. The lower sections of the conduit, and the manhole shaft piercing it, are built in precise alternating bands of Roman brickwork and opus reticulatum. Across a remote ravine to the north, the team also encountered two aqueduct bridges. One, in the characteristic style of the Acqua Paola, was intact but dry. Yet just downstream, a massive riven chunk of the Aqua Traiana's bridge lay on its side, exposing its opus signinum floor. Part of a Roman arch teetered over the bank above. Violent floods must have washed this bridge out long before the pope's engineers arrived, forcing them to build a stronger bridge just upstream. About a hundred feet of undamaged conduit along the bank revealed the same hybrid construction as the Pisciarelli sector—the floor, walls, and opus signinum lining of the Aqua Traiana were reused wherever possible, and new vaulting was applied where it was needed.

Despite the presence of the sources in the heart of Italy, it is remarkable that they, and indeed many of the remains of one of Rome's greatest aqueducts, had eluded archaeologists' best efforts to find them. Yet the surprising discoveries from the past few years are beginning to uncover a piece of Roman history that has been ignored, misunderstood, and even completely unknown since the Middle Ages . One part of this history arose from a pope's desire to elevate his stature and emulate one of antiquity's great builders, even reusing some of Trajan's earlier aqueduct in the process. Another is the small church of Santa Fiora, which reflects the desire to preserve the holiness of the spring that once fed the Aqua Traiana. As the O'Neills' search continues, there is no doubt even more of this history will be revealed.

Video: The Search for the Aqua Traiana

For the past several years, filmmakers Ted and Mike O'Neill have worked with archaeologists Rabun Taylor and Katherine Rinne to discover the remains of the Aqua Traiana, one of ancient Rome's greatest aqueducts. The short film here shows the team scouring the countryside north of Rome, discovering one of the aqueduct's spring houses, identifying construction materials and techniques unique to ancient Roman builders, exploring one of the aqueduct's channels, and pinpointing one of the locations where the remains of the Aqua Traiana were used to help build a Renaissance-era aqueduct that also fed the city's insatiable need for water.