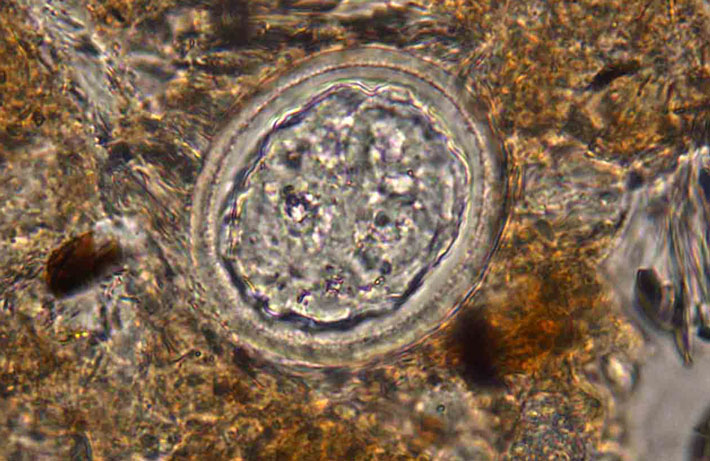

It’s hardly surprising that an Iron Age settlement in which livestock lived alongside people and open pits served as latrines would be overrun with intestinal parasites. As expected, researchers studying sediments from some of these pits at a settlement in present-day Basel, Switzerland, dating to around 100 B.C., found roundworm, whipworm, and liver fluke eggs.

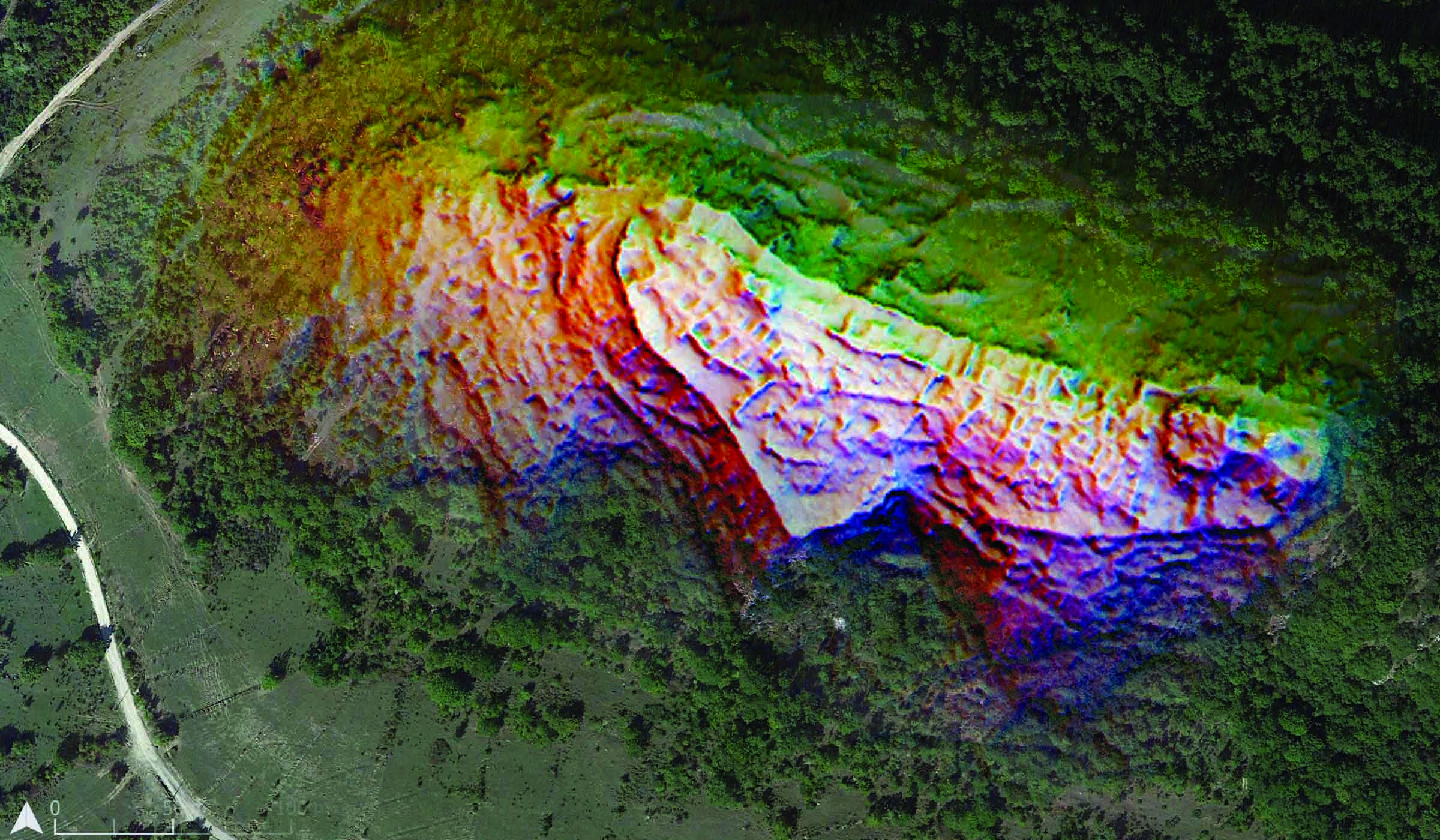

What makes their findings notable is the method they used. Archaeologists typically detect parasite eggs through “wet sieving,” in which soil is moistened and then strained, which allows a large volume of fill to be searched, but provides no information on where the eggs were originally located. Instead, at Basel, scientists have produced very thin slices of sediment that can be studied under a microscope, which preserves the location of the parasite eggs in their original setting. “You would expect the parasite eggs to be close to where the feces were,” says Sandra Pichler of the University of Basel, “but we found that the eggs get washed out by water and spread around. Even sediments without any fecal indicators still had parasite eggs.”