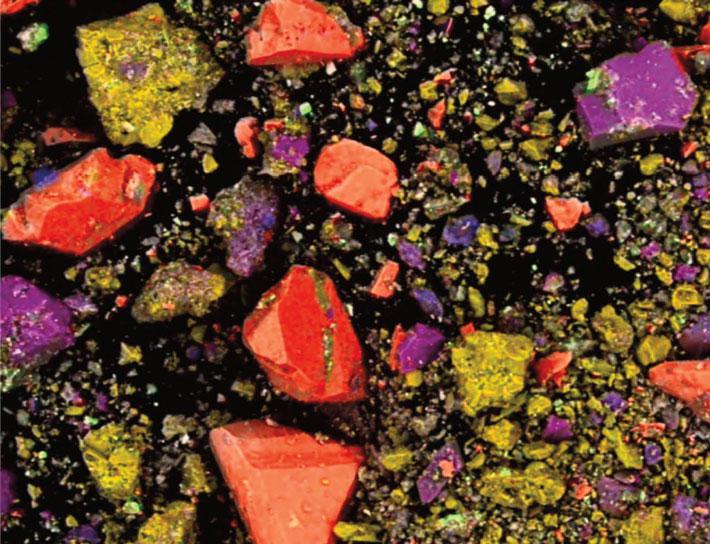

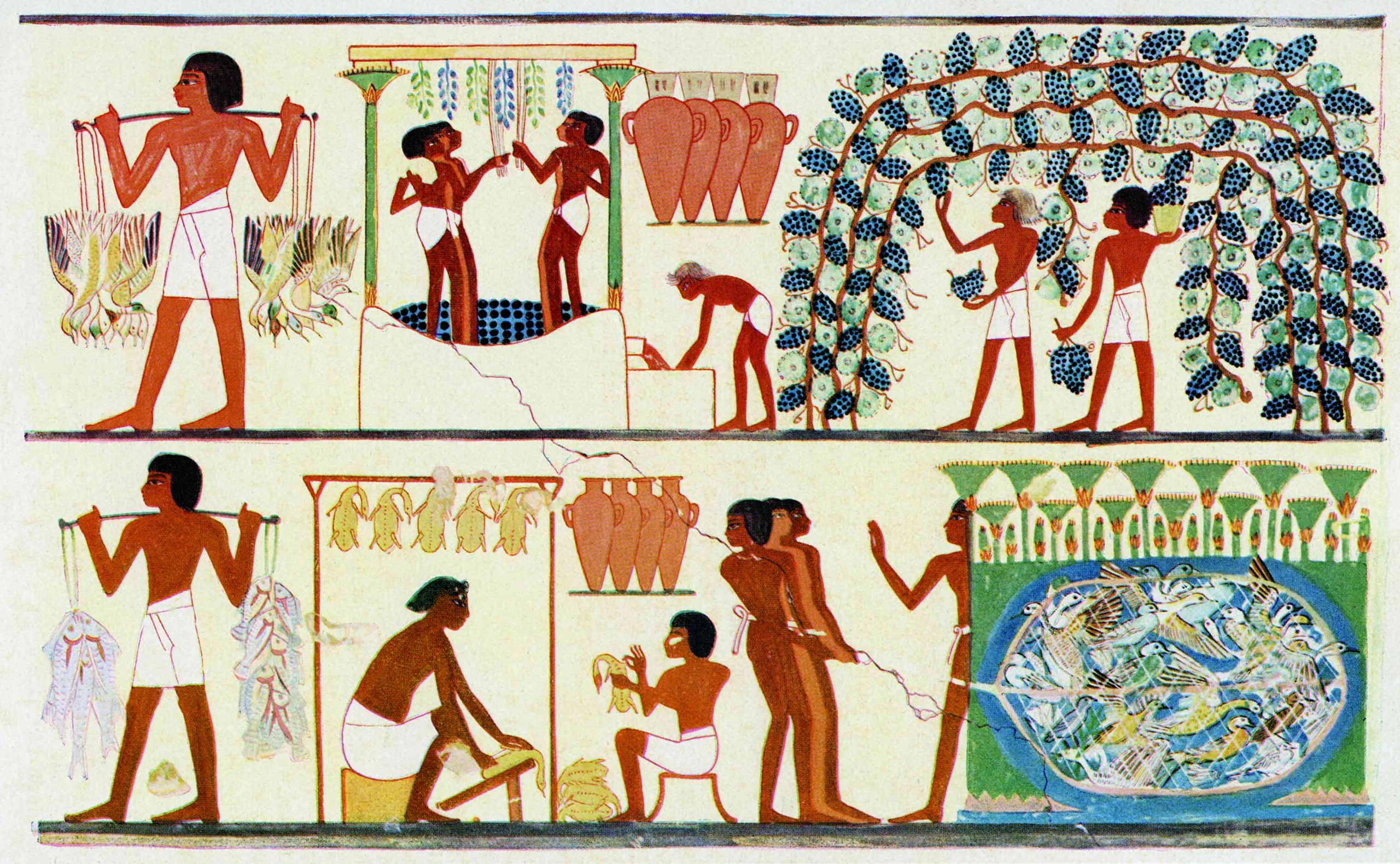

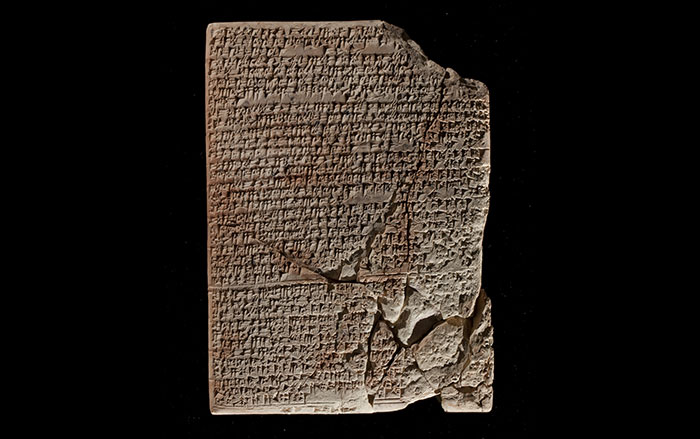

Cuneiform tablets list myriad plants imported from around the Near East that were cultivated in the gardens of Mesopotamian kings during the first millennium b.c. Since the Akkadian and Sumerian names for these plants differ from those used by modern botanists, identifying ancient flora has proven difficult. A sun-dried brick made of mud gathered near the Tigris River is now offering researchers an unprecedented peek into the variety of local plants in northern Iraq some 2,900 years ago.

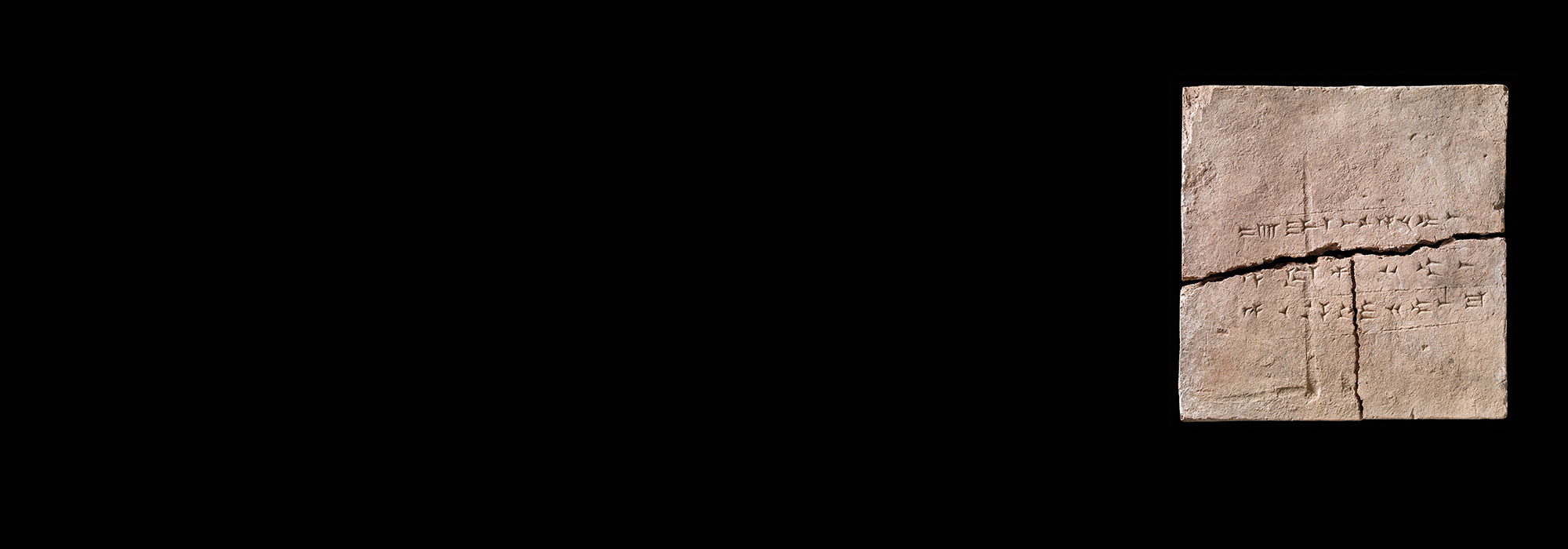

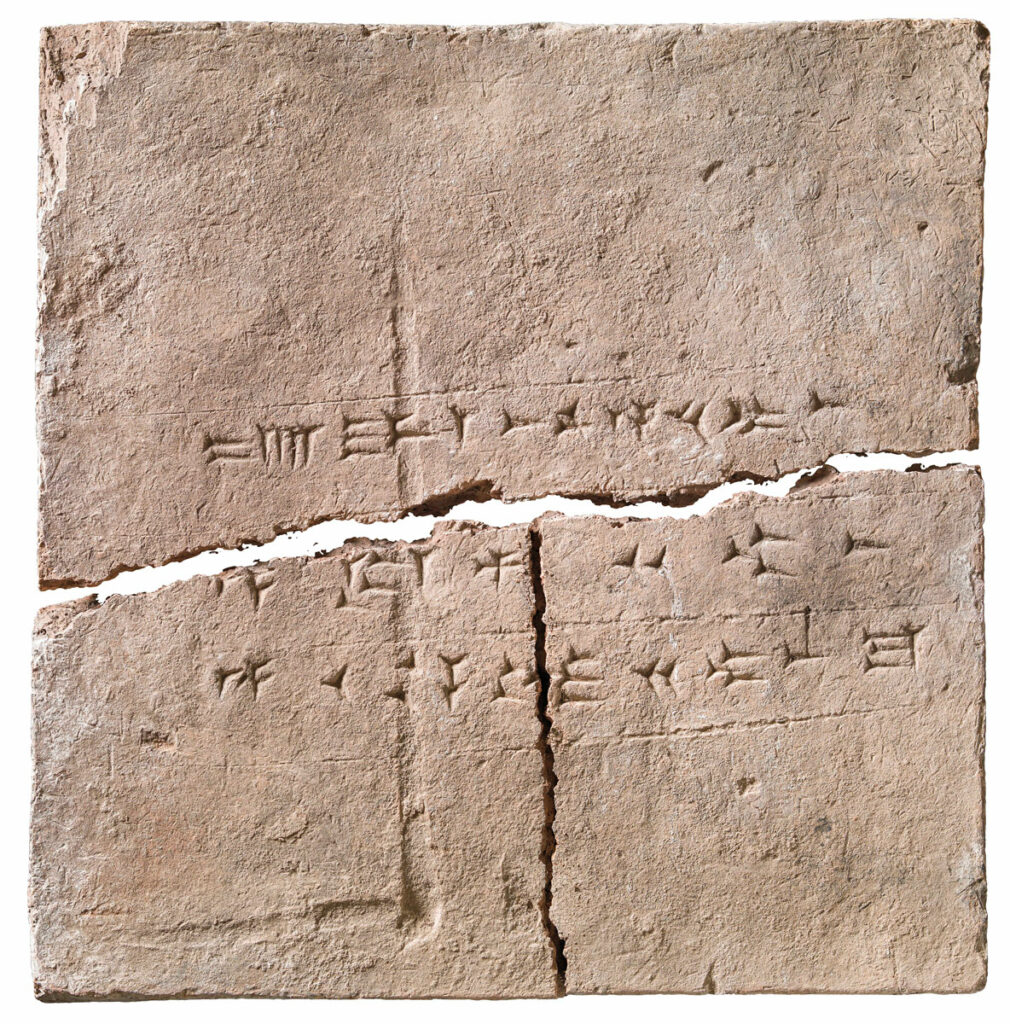

The brick, which is held by the National Museum of Denmark, was excavated in the ancient city of Nimrud. An Akkadian inscription on its surface reads, “Palace of Ashurnasirpal, Assyrian king,” referring to Ashurnasirpal II (reigned 883–859 b.c.). The text identifies the brick as having been used in the ruler’s grand palace, which was built beginning in 879 b.c., after the king made Nimrud the new capital of the Neo-Assyrian Empire (883–609 b.c.). A vertical split in the brick’s lower half presented a unique opportunity for an interdisciplinary team of researchers to study the artifact. They found traces of straw in its clay core. “This led us to wonder if sampling for ancient DNA might reveal the origins of the materials used to manufacture the brick,” says Assyriologist Troels Pank Arbøll of the University of Copenhagen.

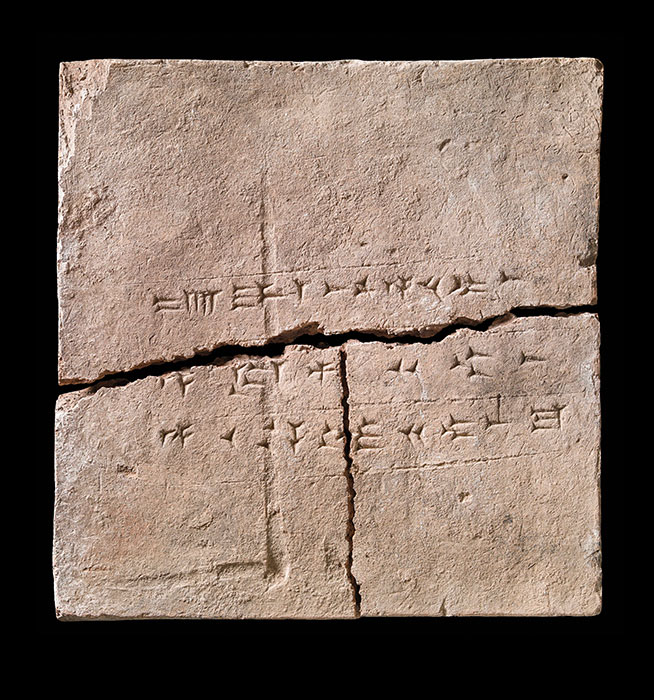

By adapting a methodology developed to extract genetic material from porous substances such as bone, researchers including biologist Sophie Lund Rasmussen of the University of Oxford were able to remove and sequence ancient plant DNA from the brick—the first time this had ever been accomplished. The team identified 34 distinct plant groups, including species of heather, birch, laurel, cultivated grasses, and umbellifers, members of a family of aromatic flowering plants including parsley. A particularly large number of samples belonged to the Brassicaceae family, evidence that cabbage grew in ancient Nimrud. “It’s currently impossible to determine with certainty whether the cabbage was wild or domesticated,” Arbøll says. “If it’s the latter, this would be an important new lead in the unresolved discussion about where and when cabbage was domesticated.”