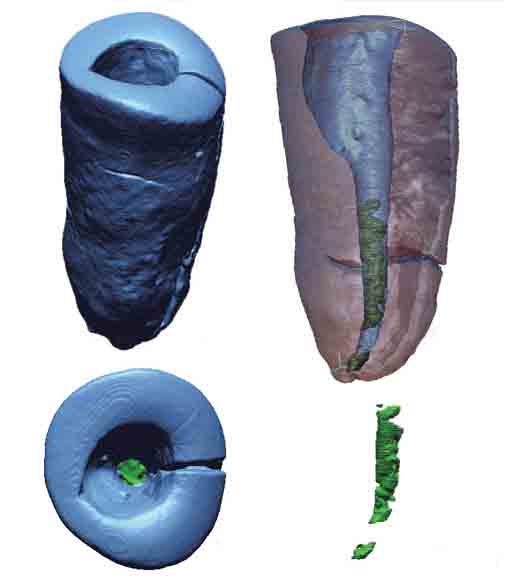

Humans have been passing through the Barrancas River Valley in what is now western Argentina since at least the end of the last Ice Age, some 10,000 years ago. But excavations starting in 2012 turned up only scant traces of early hunter-gatherers, mostly stone projectile points. Then, in 2018, archaeologists discovered that the valley was more than just a way station: They found a grave, and then another in 2023. One burial had been partially preserved—including soft tissue—by the Andean Plateau’s extreme aridity. Dated to 9,700 years ago, that burial is one of the oldest known examples of naturally mummified remains in the world. Fragments of two slippers made of vicuña leather had also survived in the grave. “We’re thinking of this landscape as a transit area, but a constantly used transit area that was very important,” says archaeologist Marcelo Morales of the University of Buenos Aires. For nomads, Morales explains, such frequently traveled routes may have made ideal burial places.

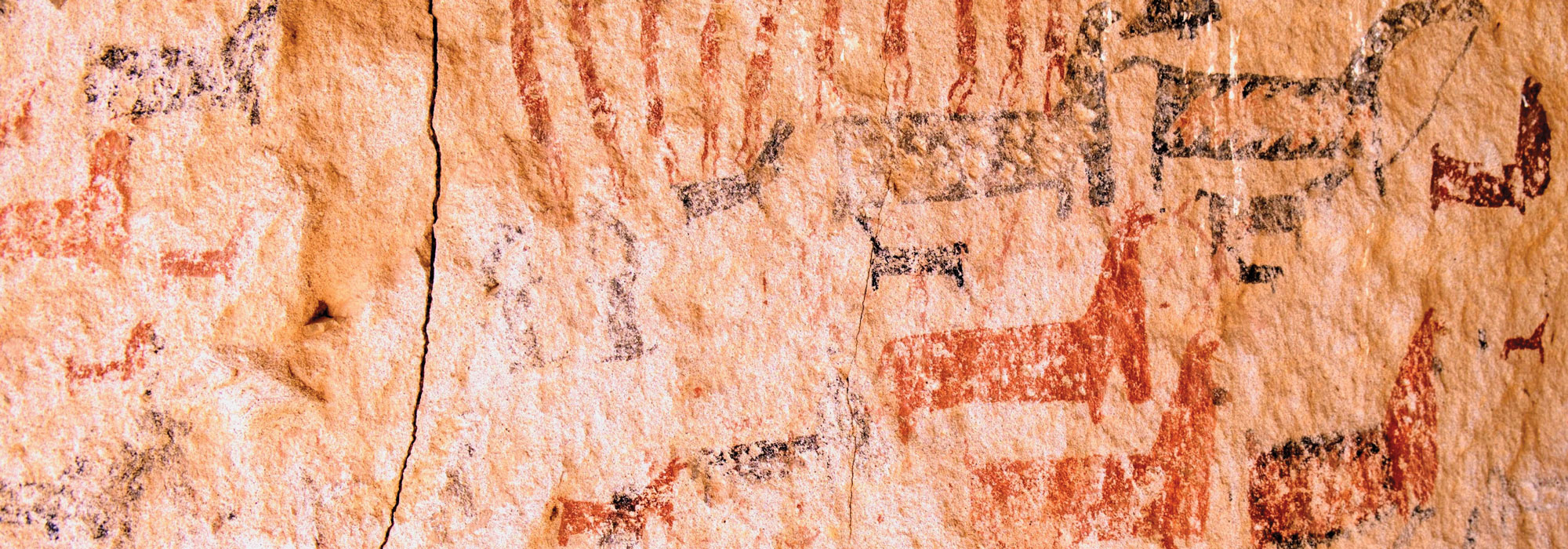

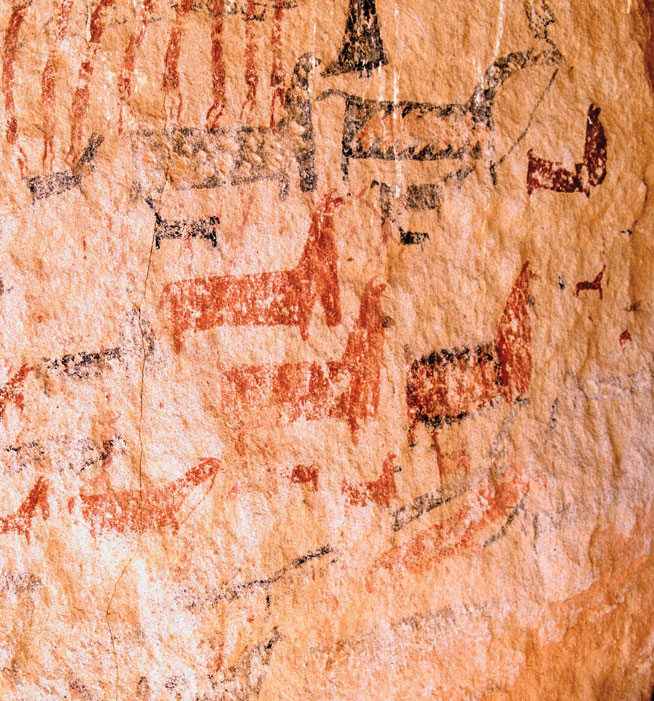

Archaeologists have now unearthed artifacts from many eras, including obsidian tools, smoking pipes, glass beads, and ceramics characteristic of far-off cultures such as the Atacama people of what is now Chile. Newly arrived travelers spent a few nights—or centuries—there to hunt, then to herd, then to trade. For at least 3,500 years, and perhaps much longer, people marked the valley’s cliffsides with paintings and carvings, more than 1,400 of which survive. There are images of condors, snakes, dancing cigar-shaped men, masks from Indigenous mythology, and Christian crosses. Nearly 60 percent of the petroglyphs feature camelids. “Llamas were a sacred animal,” says site guide Blas Alancay, whose family has lived in the town of Barrancas for generations. In just one cramped cave, researchers have identified artworks from seven distinct time periods spanning at least 3,000 years. Blocky red camelids were later joined by more svelte black-and-white patterned animals that appear leashed together and fully domesticated. Perhaps the most imposing single artifact is the “Stone Map,” a six-by-eight- foot boulder engraved sometime between 1430 and 1470, which contains a rural scene of corrals holding llamas, rheas, and canines, along with a tunic representing a man. The finds from the valley reveal how people moved, evolved, adapted, and interacted in the harsh central Andes. “In an area less than seven miles long,” says Morales, “you have a huge amount of evidence.”

THE SITE

Surveys and excavations in the Barrancas River Valley only began in the 1990s. Today, a few hundred people live in Barrancas, where the Center of Archaeological Interpretation opened in 2020. Visitors can find information about the petroglyphs, replicas of pottery, a life-size tableau of a llama caravan, and a 3-D hologram of the “Stone Map.” From the center, you can hire guides to three of the valley’s most spectacular attractions, all unmarked: the “Stone Map,” the “Caravanner’s Cave,” and the “Inca Throne.”

WHILE YOU’RE THERE

At the center, shop for handmade stoneware, wool rugs, and ponchos. You can also try llama empanadas, llama roast, and ulpada, a corn-flour drink, at El Tolar, the best—and only—cafe in town. Visitors, especially those who don’t speak Spanish, may find it easiest to contact the center in advance to arrange both lunch and a guide. On a longer trip to Jujuy and Salta Provinces, far to the north, take a break from hiking through the otherworldly ravines and tasting Torrontés wine to find impressive pre-Inca ruins at the Pucará de Tilcara, pore over another wealth of rock art at Inca Cave near Humahuaca, and see the Llullaillaco mummies at the Museum of High Altitude Archaeology in the city of Salta.