Not every notable discovery consists of a single extraordinary artifact, a previously unknown structure, or a newly revised date for an ancient technology. Some of the most significant discoveries result from ongoing work that allows archaeologists to fully comprehend a site’s scope and importance over time. Novel realizations can change what researchers thought they knew.

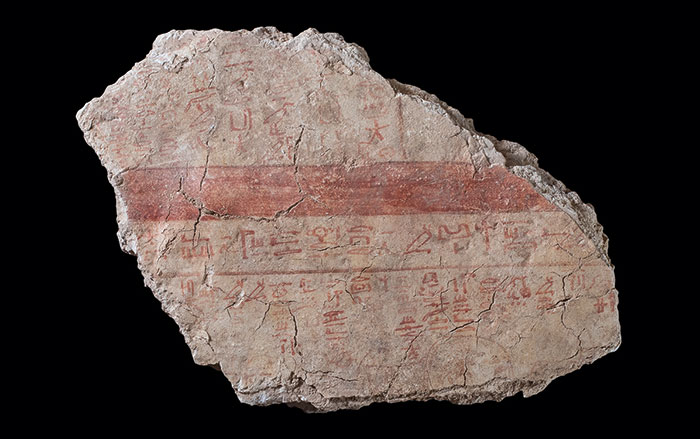

In 2019, Egyptologist Patrizia Piacentini of the University of Milan began to work at a site outside the thriving ancient frontier city of Aswan in southern Egypt. It would take five years for her to truly appreciate the site’s import. In their first season, Piacentini’s team, in cooperation with the Egyptian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities, noticed a few tombs cut into a hill on the banks of the Nile that had been looted in antiquity. Upon closer inspection, Piacentini saw dark patches in the yellow sand clearly indicating the presence of mudbrick. “Let’s try here,” she said. “I think there’s a tomb.” There was, indeed, a huge tomb containing the remains of 46 men, women, and children dating from the second century b.c. to the second century a.d., along with artifacts such as statuettes and brightly painted cartonnage, the layers of plaster and linen used to encase mummified people.

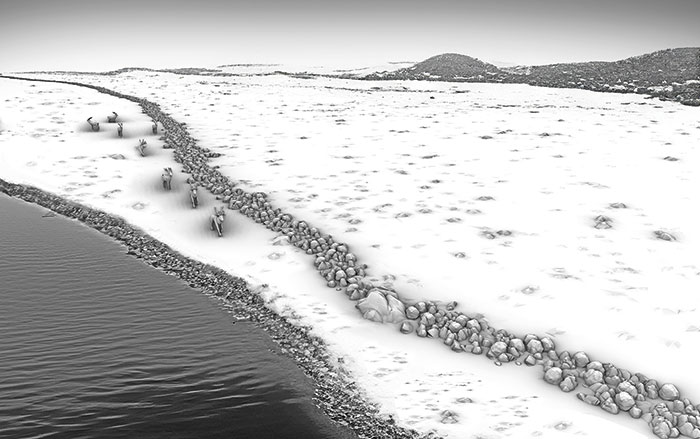

These individual finds began to create a picture of an enormous, previously unknown necropolis that the team eventually determined extends over 25 acres. “We knew the people of the Greco-Roman period in Aswan had to be buried somewhere, but we didn’t know where,” Piacentini says. “Now we do.”

It was only in 2024 that it became clear that the necropolis is unique in Egypt. While Egyptian necropolises were usually constructed on two or three levels to accommodate many burials over a long period of time, the builders of the Aswan necropolis outfitted it with no fewer than 10 levels. The necropolis includes more than 400 tombs containing the remains of thousands of people. The team has learned that, while the top levels were reserved for wealthy people, including the chief of the Egyptian army in the second century b.c., the lower levels explored in 2024 were used to bury members of the middle class. “We want to understand who these people were and how the necropolis was organized,” says Piacentini. Like many great discoveries, the answers to these questions will be the cumulative result of past and future work.