Although today it stands in ruins, Glastonbury Abbey, in Somerset, England, is still a powerfully evocative place, shrouded in history, religion, and mythology. One story claims that Joseph of Arimathea, legendary keeper of the Holy Grail, founded the first Christian church in Britain at Glastonbury shortly after the death of Christ. Another holds that in 1191, monks from the abbey unearthed a hollowed-out log containing two bodies and an inscribed cross that read: “Here lies buried King Arthur and his wife Guinevere.”

The traditions and myths surrounding Glastonbury Abbey are perhaps key among the reasons it developed into one of the most important—and wealthiest—monasteries in Europe. But skeptics have long decried these stories as inventions by medieval monks to fill the abbey’s coffers, especially after a massive fire destroyed the monastery in 1184. Archaeologist Roberta Gilchrist of the University of Reading has recently completed a multiyear project aimed at constructing a new history of Glastonbury Abbey, unencumbered by previous assumptions based solely on myth. “Glastonbury Abbey holds a unique place in the history of medieval monasticism and in the development of English cultural identity,” says Gilchrist. “Yet despite its historical and cultural significance, relatively little was known about the abbey’s archaeology.”

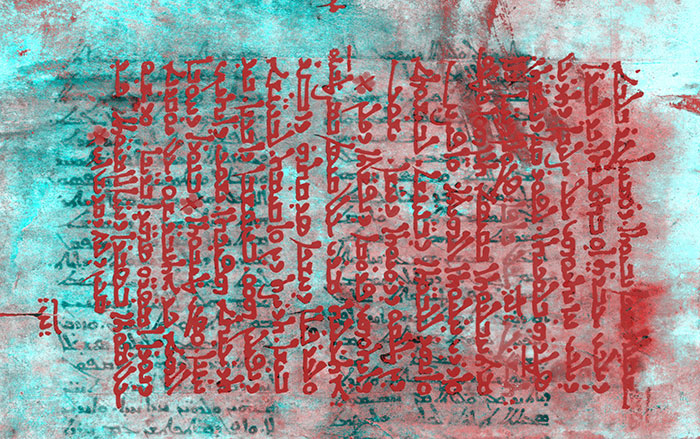

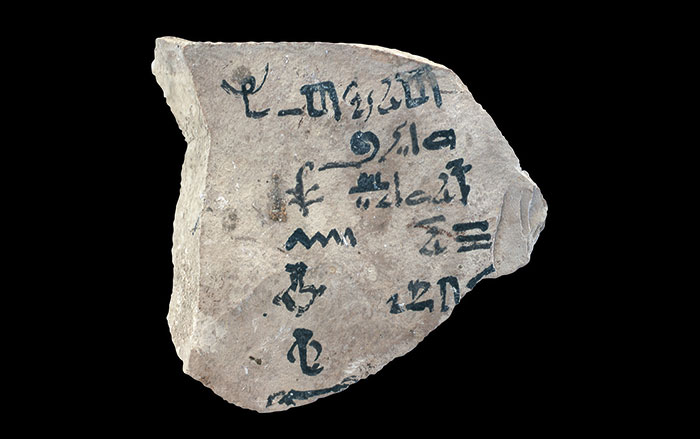

Most of the Glastonbury Abbey Project’s efforts were focused on reevaluating data from previous excavations. From 1904 to 1979, at least 36 excavations were completed, but much of that material was lost or never published. It has also been frequently misinterpreted. Gilchrist and her team have spent several years combing through a century’s worth of archives, as well as conducting new radiocarbon dating and chemical composition analysis on previously excavated artifacts. “Our goals were to assess the scholarly significance of the excavations and provide a new historical source of evidence for understanding the site,” says Gilchrist.

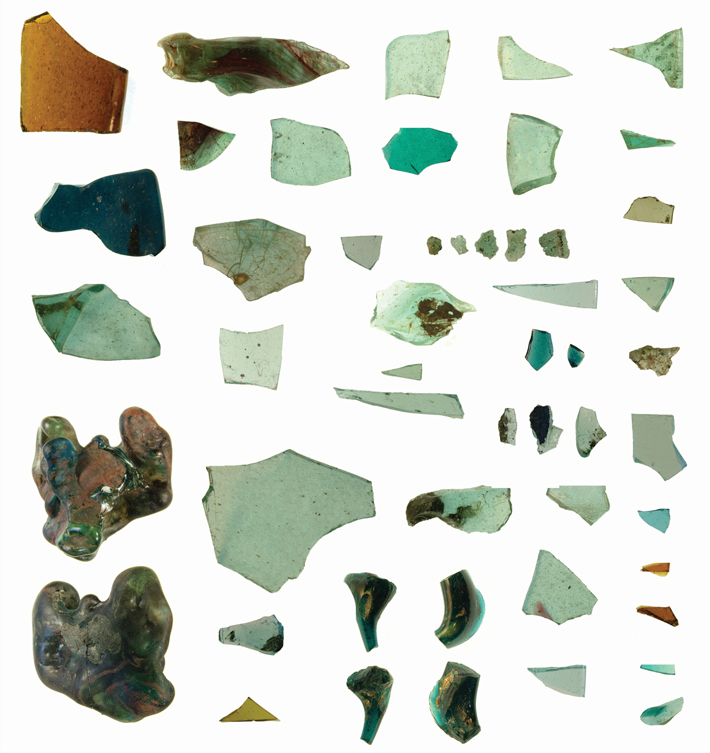

The project’s discoveries underscore Glastonbury’s long and complex history, including newly identified evidence of Roman and Saxon activity that predates the abbey’s foundation. A reassessment of glass-producing furnaces on the site proved not only that Saxon workers were recycling Roman glass imported from Europe, but also that the furnaces are nearly 300 years older than expected and are associated with the construction of the first stone churches around A.D. 700. According to Gilchrist, this would make the site’s glass manufacturing complex among the earliest and most substantial in Saxon England.

Researchers also reevaluated the purported site of King Arthur’s grave. Both the skeletal remains and the inscribed cross disappeared after the dissolution of the abbey in 1539, but archaeologist Ralegh Radford claimed to have found the original burial site when he excavated at Glastonbury during the 1950s and 1960s. Unfortunately, there is little proof connecting that site with the famous king. “Radford may have exaggerated his evidence,” says Gilchrist. “Reassessment of his excavation records shows that this was merely a pit in a cemetery, dating to sometime between the eleventh and fifteenth centuries.”

Analysis of the twelfth-century abbey church indicates that the monks themselves purposefully promoted the site’s historic reputation. As they rebuilt the church after the great fire in 1184, instead of using contemporary architectural styles, they inserted antiquated and retrospective elements, apparently to deliberately feign antiquity.

There is no doubt that many of the myths surrounding Glastonbury Abbey were at least partially created or propagated in both medieval and modern times. However, according to Gilchrist, too much media attention has focused on the new evidence that seems to refute Glastonbury’s mythical traditions. For her, there is room for both archaeology and legend to coexist. “At Glastonbury, people respond on a personal level to the place and its historical, legendary, and spiritual resonances. We didn’t claim to disprove the legendary associations, nor would we wish to,” she says. “Archaeology can help us to understand how legends evolve and what people in the past believed.” In fact, she notes, the project has actually uncovered the first definitive proof of occupation at the Glastonbury Abbey site during the fifth century—when Arthur allegedly lived.