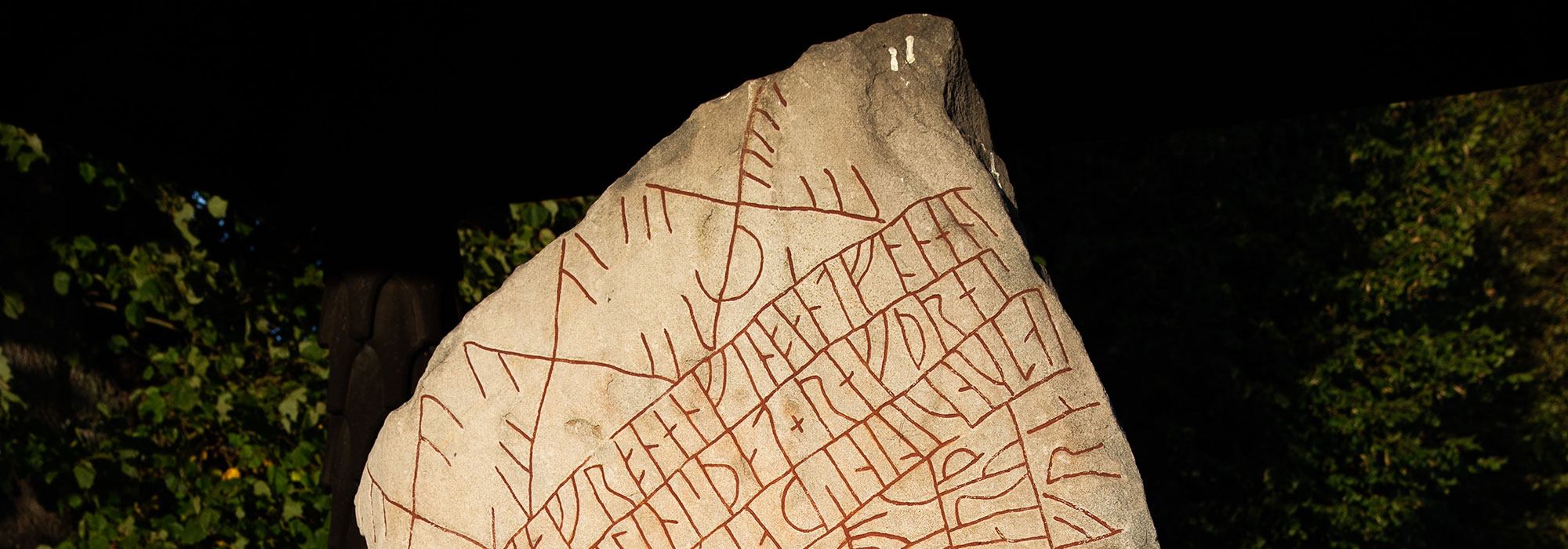

In the language of the Vikings, Old Norse, rök means “monolith,” and no other runestone stands out from its peers in more ways than Sweden’s Rök. The five-ton stone measures eight feet tall and its five sides are covered with the longest runic inscription in existence—some 760 runes divided into 28 lines. And, while the vast majority of runestones date to after the mid-tenth century A.D., the Rök was inscribed much earlier, around A.D. 800. “It’s the emperor of runestones,” says Henrik Williams, a runologist at Uppsala University. “Nothing can compare with it.”

Although scholars are united in recognizing the Rök’s singularity, with regard to its meaning all they can agree on is that it was set up by a local chieftain named Varinn as a memorial to his son Vamoth. The stone’s inscription has defied attempts at interpretation since the mid-nineteenth century, when it was transcribed after the Rök was removed from a structure into which it had been built centuries earlier. Decoding the inscription is made especially difficult as it features several styles of writing, including the earliest form of runes, called Elder Futhark, and two types of cipher. It’s not clear in what order the sections of the text are supposed to be read—or if it was even intended to be understood by mortals at all. “I don’t think this was ever meant to be read by humans,” says Bo Gräslund, an archaeologist at Uppsala University. “It was only meant for the gods.”

Now, a team composed of Williams, Gräslund, University of Gothenburg linguist Per Holmberg, and Stockholm University historian of religion Olof Sundqvist has developed a new interpretation of the inscription that ties it to themes in Norse mythology and to a devastating sixth-century climate crisis. The very beginning of the inscription—scholars generally agree it is the beginning—describes Vamoth as “death-doomed.” While most runestones memorialize the dead, says Williams, this phrase is unique to the Rök and suggests that the young man was fated to die for a particular reason.

Based on a number of allusions strewn throughout the inscription, the researchers believe that Vamoth perished so he could join the army of the chief Norse god, Odin, in Ragnarok, the apocalyptic battle pitting the Viking gods against their enemies, the giants. In one section, the researchers have detected a reference to one of the chief giants, the monstrous wolf Fenrir, swallowing the sun, the act that sets Ragnarok in motion. Another section describes Fenrir facing off against 20 kings—members of Odin’s army—on the Grove of Sparks, a name for the Ragnarok battlefield. And, near the end of the inscription, the team has gleaned a reference to Odin’s son Vitharr, who vanquishes Fenrir after the creature kills his father. Only then can the sun’s daughter take her mother’s place in the sky.

For the team, another key to the inscription’s meaning is found in a line that mentions someone “who nine generations ago lost their life.” Given that the runestone dates to around A.D. 800, and allowing 30 years per generation, this event would have occurred in the early sixth century. The scholars believe the line describes the death of the sun and refers to a period beginning in A.D. 536 when a series of volcanic eruptions is known to have blocked sunlight for several years, leading to mass starvation.

This reference to events of nearly three centuries earlier, the researchers suggest, was likely prompted by a number of happenings reminiscent of those harrowing times. “We know that there were solar storms that turned the sky red and would have caused very cold summers,” Williams says. “And there was a near-total solar eclipse that would have scared the hell out of people.” With the threat of a crisis looming, Vamoth is described on the runestone as having been cut down before his time in order to help Odin’s army defeat the giants, ensuring that the sun would continue to shine.

Video: Reading the Rök Runestone

To watch a video of Henrik Williams reading the Rök runestone’s inscription, click below.