United States Army Air Forces 2nd Lt. William J. McGowan was 23 years old when he died near the village of Moon-sur-Elle in northern France. McGowan had grown up in the small town of Benson in western Minnesota, where he loved to ski. He attended Benson High School, St. Thomas Military Academy, and then the Missouri School of Journalism, where he received his degree in 1942. He worked as a journalist and editor, first for the United Press news service in Madison, Wisconsin, and then for his hometown paper, the Swift County Monitor-News, of which his father was the editor and publisher.

In 1943, McGowan was called to Eagle Pass Army Airfield in southern Texas for training. In December, he earned his pilot’s silver wings and his commission. A month later, he moved on to Harding Airfield in Baton Rouge for flight training on the P-47 Thunderbolt, the beloved workhorse of World War II American aviation. There he married Suzanne “Suki” Schaefer of Winona, Minnesota, and two months later was sent to England aboard Queen Mary. On May 15, he joined the 391st Fighter Squadron, 366th Fighter Group. Between May and June 5, McGowan made 10 sorties and flew four combat missions.

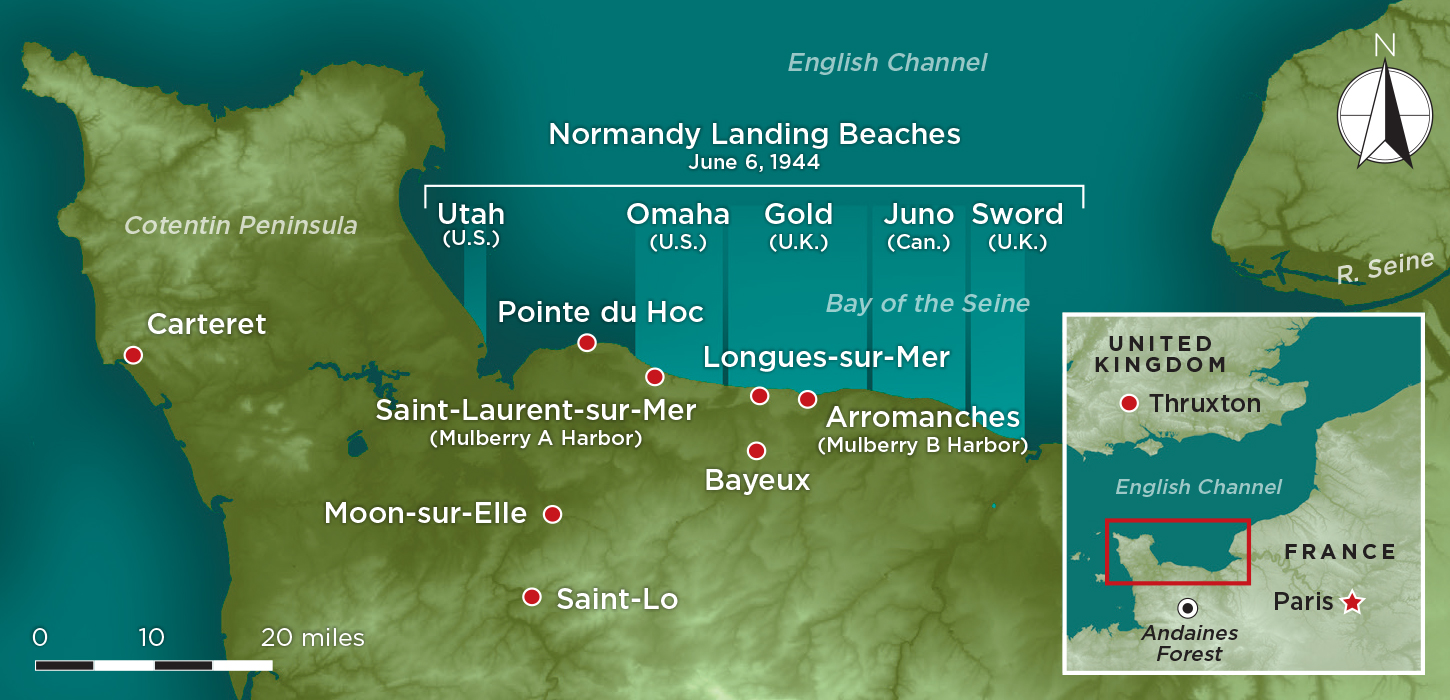

At 3:15 p.m. on June 6, 1944, D-Day, McGowan set out from Royal Air Force Thruxton in Hampshire in southern England on a mission to target the Lison train station and enemy convoys moving northeast toward Bayeux. According to the Missing Air Crew Report given by his wingman, Flight Officer Paul E. Stryker, the next day, after they seized “a target of opportunity” and dropped their fragmentation bombs on a passing German train, McGowan’s Thunderbolt was hit by antiaircraft fire at 500 feet, too low for him to safely parachute from his plane. “I was taking evasive action and about 1000', I noticed his plane was in flames and was going into a spin,” relayed Stryker. “He spun it to the ground and the whole ship burst in to flame.”

Three years later, a team from the American Graves Registration Command (AGRC) visited an area where French civilians described having seen a downed aircraft burning for a full day in a field near Moon-sur-Elle. The AGRC team removed pieces of the wreckage, some of which was embedded up to four feet in the ground, and identified the plane as McGowan’s using a serial number on one of its machine guns. Tiny pieces of charred human remains villagers had found in 1944 and buried under the plane’s propeller had disintegrated. The villagers had also located McGowan’s dog tags, and had given them to American troops setting up antiaircraft batteries in the field. McGowan was declared unrecoverable and the AGRC recommended “no further action be taken.”

But, more than 60 years later, on a return trip to Moon-sur-Elle in 2010, a team from the Joint POW/MIA Accounting Command (now the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency, or DPAA), resurveyed the wreck site, reinterviewed witnesses, and found additional aircraft debris. Upon learning that the land where the crash site is located had been put up for sale, DPAA recommended that it be excavated and invited archaeologists and students from the forensic aviation course at Nova Scotia’s Saint Mary’s University to Normandy. During their one-month field season in the summer of 2018, the team excavated 861 square feet of cornfield, where they unearthed human teeth, small pieces of bone, fragments of aircraft, 350 .50 caliber projectiles and casings, and an Army Air Corps officer’s collar insignia pin. Using the pin and dental records, the remains were eventually identified as McGowan’s. And, while the effort to identify missing World War II personnel in all theaters continues, much depends on testimony of eyewitnesses, few of whom survive, and such successes, particularly in the European Theater, are rare.

The archaeology of D-Day and the Battle of Normandy is not confined to a search for downed aircraft and missing persons. Given the colossal military, engineering, and personnel scale of the D-Day landings and the subsequent battle for France that raged for 80 days until the liberation of Paris on August 25, vast amounts of evidence of men and materiel survive for archaeologists to explore and document. Concrete gun emplacements, bunkers, and batteries of the Atlantic Wall still pepper the battle-scarred coastline and fields of Normandy, and rusted amphibious vehicles that sank or were stranded before reaching Omaha Beach still lie in the Bay of the Seine. Artifacts including tanks and jeeps, tins of food and tubes of shaving cream, weapons, ammunition, and helmets are collected in the museums that dot the Normandy shoreline, the buildings’ large glass windows framing views of the bay and beyond, to England. And tens of thousands of soldiers and civilians are buried in the region’s cemeteries, and some, perhaps many, still lie in its rich soil.

The landscape, too, provides archaeological evidence of the campaign. Individual foxholes and millions of bomb craters pock the forest floor of the woodlands where the Germans set up their supply depots. Disjointed remnants of the artificial harbors at Arromanches and Saint-Laurent-sur-Mer jut from the bay, especially at low tide. And there is even evidence of D-Day in the sands of Omaha Beach. On that six-mile stretch of light-gray sand, where 34,250 American troops landed, researchers have identified shrapnel as well as iron and glass beads created by munitions explosions nearly eight decades ago, minuscule pieces of evidence of the cataclysmic events of that day.

Archaeologists studying D-Day and the Battle of Normandy face many challenges, not least of which is that the erasure of material evidence began the day after the war ended, says archaeologist Vincent Carpentier of France’s National Institute of Preventive Archaeological Research. The rebuilding of towns damaged in the war, urban development, and agriculture have obliterated evidence of battle sites. Coastal erosion, sea level rise, and weather threaten the remnants of the Atlantic Wall and artificial harbors. And thieves have taken artifacts and damaged sites. Nonetheless, what began in the 1960s and 1970s as “bunker archaeology” conducted by amateurs is now a rapidly growing discipline focused on survey, documentation, excavation, and protection.

In light of successful archaeological studies conducted across Europe at World War I sites and the recent passing of that conflict’s 100th anniversary, scholars’ attentions have shifted to the next great twentieth-century conflict. “The Second World War, like the First, was once thought to be so well documented historically that archaeology could add nothing and that these events were too recent to be excavated,” says University of Bristol archaeologist Nicholas Saunders. “We now know that nothing could be further from the truth—the First World War has led the way, but the Second is catching up fast. We are on the cusp of time where history becomes archaeology and the last eyewitnesses are passing on.”

Yet World War II archaeologists are confronted by a different landscape. “The landscape legacy of combat operations in the Western European Theater of World War II is very different from that of World War I,” says University of Toronto geographer and archaeologist David Passmore. “Instead of static and heavily cratered trench lines, World War II’s combination of mobile warfare and air power left abundant earthwork field fortifications for shelter and combat alongside shell and bomb craters, even well behind the front lines. Despite the massive damage done to the landscape during the war, though, there is very little to see of the actual battles in the modern landscape.”

In May of 1942, Hitler decided that in order to defend Fortress Europe against an Allied invasion, he needed a 2,400-mile wall stretching from Scandinavia to Spain. More than 4,000 acres of concrete and 5 percent of Germany’s annual steel production—equal to that used for all the tanks built that year—were employed to build portions of the Atlantic Wall in preparation for the anticipated Allied landings in France. Up until then, the Germans’ emphasis had been on defending ports such as Calais where they were confident the landings would take place. But Field Marshal Erwin Rommel, who had taken over supervision of the wall’s construction in 1943 and harbored, along with many of Hitler’s military advisers, grave doubts about its efficacy, focused instead on the poorly defended lower Normandy coast. There, the Germans erected hundreds of steel defensive obstacles and built batteries, bunkers, and casemates, some of which were even painted in trompe l’oeil to look like houses, seaside cafes, and bars overlooking the coast’s sometimes sunny but often stormy beaches.

Archaeological investigation of many Atlantic Wall sites has focused on construction methods, gun locations, and how complete these defenses were on June 6, which was, Carpentier says, “often very different from the official standards detailed in the archives.” Using information gathered during geophysical survey and excavations, archaeologists have showed that, although the Second World War marked a high point in the production of weaponry and military installations, many of the Atlantic Wall structures were hastily built using a restricted range of available materials. For example, explains Carpentier, contrary to German propaganda, concrete was actually used more sparingly than brick, wood, and stone. Researchers have also been able to create a typology and chronology of techniques and materials employed across many Atlantic Wall sites. Far from serving just as a catalog, this has enabled them to identify variation between structures built between 1940 and 1943 and those built after 1943, whose construction Carpentier describes as “anarchic”—a clear product of Hitler’s increasing paranoia over the threat of invasion.

One of the best preserved of the 30 German batteries that defended the landing beaches is at Longues-sur-Mer. It consisted of four massive concrete casemates built in 1943 about 1,000 feet inland from the coastline between Gold and Omaha Beaches. Each casemate housed one 155 mm gun. Unlike most other metal armaments, which were removed for the raw materials or stolen after the war, one of these guns remains in situ.

In the end, Hitler’s wall was an arrogant folly. Most of the coastal batteries were disabled by bombing runs before the landings or quickly overrun, and the Atlantic Wall was breached in a single day. The most harrowing breach came at Pointe du Hoc between Utah and Omaha Beaches. At 5:50 a.m., the U.S. Navy started to bombard the point. Less than an hour and a half later, men of the 2nd Ranger Battalion disembarked from their landing craft and began to scale the 100-foot cliffs under enemy fire, reaching the top by 7:40 a.m. Although the Germans had previously moved the massive guns pointed directly at Utah Beach, the Rangers soon located them hidden in the thick hedgerows known as the bocage and destroyed them.

The story of the Allied victory in Europe is often told as one of air superiority. At no time was this advantage more manifest than just before, during, and immediately after D-Day. Between June 5 and 6, the Allies dropped 18,000 tons of bombs on the Normandy coast, countryside, and forests, killing and wounding thousands of soldiers and civilians, and destroying or disabling fortifications, road and rail networks, and supply facilities behind the beachheads. But unlike the agricultural fields, where large bomb craters were quickly filled in after the war, “it is in the woodlands and forests where archaeological evidence of combat can still be found,” says Passmore. “Here is a landscape that is telling you something, and you have to try to understand it.”

Much of Passmore’s work has focused on large, well-preserved German ammunition and fuel depots in several of Normandy’s larger forests. Passmore says that, at first, he and his team, which includes geographer Stephan Harrison of the University of Exeter and historian and geographer David Capps Tunwell of the University of Caen, were surprised to see that the huge earthwork bunkers that are the distinctive archaeological signature of these facilities still existed. Due to the danger of unretrieved live ordnance and French laws governing management of national forests, there has been no opportunity for archaeologists to excavate these structures. But by using noninvasive field mapping, survey, and lidar, the team has been able to determine the number and geographical distribution of fuel and ammunition bunkers at several depot sites and to compare their findings with German army logistics records. In Andaines Forest, for example, nearly 900 individual earthwork features, including storage bunkers, trenches, and vehicle shelters, have been mapped in Lager Berta and Lager Martha, among the largest fuel and ammunition depots, respectively, in Normandy prior to D-Day.

The landscape of Andaines Forest also helps illuminate the dominance of air power in the Normandy campaign. “We have very well-preserved bomb-crater evidence of Allied air raids conducted during June and July of 1944,” says Passmore. “It’s interesting to look at the narratives around the campaign and at what assumptions were being made, especially about how well, or poorly, supplied the Germans were. There’s a fascinating story starting to emerge of where the Germans stored the fuel they did have, of how the Allies gathered intelligence, and of how successful they were at targeting these sites.” For example, extensive cratering around Lager Berta testifies to the effectiveness of aerial attacks, and it is known from German records that the fuel depot had to be abandoned a few days after a major raid on June 13 conducted by the U.S. 397th Bomb Group in B-26B Marauders. “It’s interesting to note that Allied intelligence failed to properly identify or target Lager Martha, and that this major ammunition depot continued to operate until being overrun by American forces on August 14, at which point it still held substantial stocks of ammunition,” says Passmore. “These lines of evidence illustrate the difficulties faced by the Allies both in gathering intelligence on the supply depot network and in accurately striking those targets concealed in large forests.”

Bomb-cratered landscapes can also tell the heartrending tale of the civilian cost of Allied air operations over Normandy. In the daily operational records of air squadrons, it is rare to find any acknowledgment that attacks on targets in towns, villages, and the surrounding countryside may have incurred civilian casualties, Passmore says. But it is becoming clear as research continues that as many as 60,000 to 70,000 French civilians died as a result of air attacks in support of the Normandy campaign and later operations across France. “This narrative warrants more attention,” says Passmore, “and archaeology can make a significant contribution by carefully documenting the survival of landscapes that testify to the extent, range, and intensity of the attacks that brought civilians in harm’s way tens, or even hundreds, of miles behind the front.”

The D-Day landings were only the beginning of the Battle of Normandy. As the Allied soldiers advanced beyond Omaha, Utah, Sword, Gold, and Juno Beaches, an astonishing engineering project was undertaken in the same waters across which tens of thousands of troops had traveled from England. Codenamed Mulberry, two artificial harbors, one off Omaha Beach at Saint-Laurent-sur-Mer (Mulberry A) and the other off Gold Beach at Arromanches (Mulberry B) were constructed by the British in just 12 days after the landings. These harbors, composed of concrete caissons and steel roadways that had been made in the United Kingdom in secret and towed across the Channel, along with ships to scuttle and steel-reinforced caissons to sink to create breakwaters, were swiftly operational. Mulberry A was so severely damaged by a storm on June 19 that it had to be abandoned, but Mulberry B was used for 10 months, allowing more than four million tons of supplies, half a million vehicles, and more than 2.5 million men to land on the continent.

For the 60th anniversary of the D-Day landings in 2004, a concerted effort was begun to document and conserve the remains of the harbors, which had been threatened by looting for six decades, and more recently by sea level rise. By diving and using sonar, archaeologists have surveyed more than 1,200 acres and documented more than 600,000 tons of concrete remains, 3.5 miles of jetties and dikes, 33 landing platforms, and nine miles of floating pontoons, along with sunken vehicles, including at least 30 Sherman tanks once destined for the roads to Berlin.

By day’s end on June 6, the Allies had gained a foothold on the continent, but at tremendous cost—2,499 American soldiers lost their lives that day. For more than seven decades, one of these soldiers, 2nd Lt. William J. McGowan, lay in the field where he had died. But in 2021, following his family’s wishes, the Air Medal and Purple Heart recipient will be buried at the Normandy American Cemetery in Colleville-sur-Mer overlooking Omaha Beach. McGowan’s uncle, for whom he was named, is also buried in France, at the Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery north of Verdun, where 14,246 men who died in World War I lie.

McGowan will likely be the last American soldier to be interred in the Colleville-sur-Mer cemetery’s hallowed ground, as the rules for burial there are strict, and it has become difficult for the military to verify details of service. A bronze rosette will be placed next to his name on the cemetery’s Wall of the Missing to signal that he has been accounted for—only the twentieth such marker for the 1,557 missing soldiers of D-Day and the Battle of Normandy who are listed there. In many ways, McGowan’s story since the evening of June 6, 1944, embodies the archaeology of D-Day. There are primary sources such as military records and photographs and eyewitness testimonies including Stryker’s report and the memories of the villagers. Surveys and excavations have uncovered artifacts, including pieces of McGowan’s plane, and the site has been heavily disturbed by decades of farming. And the impending sale of the land compelled the most recent fieldwork, which used the latest scientific techniques.

In 2011, near the spot where his remains were found, villagers dedicated a stone monument to McGowan. In attendance at the ceremony were Agnes de Puthod and Pierre Labbé, both of whom, as children, had witnessed McGowan’s P-47 Thunderbolt crash, and both of whom described seeing him directing his plane toward the field to avoid hitting the village.

The inscription on the memorial plaque reads:

Lest We Forget

En homage à l’aviateur Americain

Lt. William J. McGowan

Age 23 from Benson, Minnesota, USA

Who gave his life near this location

D-Day 6 June 1944

“Let there be Peace on Earth, and let it begin with me”

At the end of World War II, nearly 79,000 U.S. service members were missing. At the time the announcement that McGowan’s remains had been identified was made in January 2020, 72,639 were still unaccounted for. At least 30,000 of them are thought to be recoverable.