Two Medicine River in western Montana flows from a glacial lake high in the Rocky Mountains to cut through some 90 miles of rolling prairie on the Blackfeet Indian Reservation. Its banks form gentle slopes in some sections, and steep, low cliffs in others. From a promontory known as the Magee site that overlooks a sudden, vertiginous drop into the river valley, both types of riverbank are visible. Archaeologists now know that sometime around A.D. 1500, the ancestors of the Blackfoot, a culture known to archaeologists as the Old Women’s Phase (after a Blackfoot mythological figure) arranged thousands of stones on the approaches to this high bit of prairie to enable large groups of men, women, and children to drive dozens or even hundreds of buffalo across the landscape to this spot. The buffalo driven to the edge of the promontory would fall to their deaths, making it possible for a tribe to feed themselves through another season and creating a surplus of meat that would have been a valuable trading commodity. University of Arizona archaeologist Maria Nieves Zedeño and her team spent weeks here searching through short fescue grass and blue grama looking for subtle signs of rock rings, cairns, and other stone alignments that are clues to one of the most effective hunting strategies ever devised.

The buffalo jump, as it is termed, is surprisingly sophisticated. Romantic nineteenth-century paintings depict Native American men urging improbably vast buffalo herds off gigantic cliffs. In reality, buffalo jumps are often modest bluffs. They sit at the end of complex sequences of natural and constructed landmarks, called drive-line systems, that can stretch for many miles, linking buffalo watering holes to other points on the prairie with the intention of drawing the buffalo ever closer to the cliff itself. Archaeologists have long recognized that nomadic prehistoric Native Americans such as the ancestral Blackfoot (“Blackfeet” refers specifically to tribal members now living in Montana) constructed cairns whose function was to funnel buffalo herds toward cliffs. But Zedeño believes that here in the northwestern plains, where the prairie and the Rocky Mountains meet, the elaborate and dense stone architecture constructed by the people of the Old Women’s Phase requires that our vision of them as simple bands of opportunistic buffalo hunters needs to change. “What happened here is an anomaly,” says Zedeño as she looks across the valley toward another jump site, known as Stranglewolf. “We have 11 separate, elaborate drive-line systems in just a 20-mile stretch of Two Medicine River. That took coordination and a level of planning for the future that haven’t normally been associated with nomadic people in this part of the world.”

Previously, many scholars thought that with the coming of horses, guns, and long-distance trade in the eighteenth century, the Blackfoot were able to accumulate wealth and constitute themselves into well-organized tribes with full-time chiefs who were supported by secret societies whose rituals assured success in the hunt. But Zedeño and her colleagues argue that these social changes came as early as A.D. 900, when a dramatic increase in precipitation converted the northern plains into lush grasslands, leading to a surge in the buffalo population in this part of Montana. She explains, “We think this climatic bonanza attracted hunters to colonize these areas, and that what you see with the jumps that begin to be built around this time is really landscape engineering that would have required a complex system of leadership.”

The Old Women’s Phase people did not leave behind elaborate burials or evidence of long-term storage facilities, signs that archaeologists have typically used to measure the social complexity of prehistoric societies. Scholars therefore believed that these buffalo-hunting people were essentially simple foragers, without any of the complex political arrangements that organized farmers to the east or the fishing cultures of the Northwest Coast had. “Bison hunters have been dismissed as being not as sophisticated as other cultures,” says Royal Alberta Museum archaeologist Jack Brink, who excavated at Canada’s Heads-Smashed-In, a noted buffalo jump. “There was this idea that they were opportunistic hunters skulking across the northern plains. But what we’re finding is that their way of life was complex and thought out in ways that reflected powerful social controls.”

Zedeño says that the very landscape these people left behind shows they were not simple bands of hunters, but members of a culture who could organize themselves periodically in large groups to accomplish a higher goal. She says that previous generations of scholars have focused on buffalo jump sites in isolation, without putting them in the larger context of the stone monuments that surround them. As a consequence, they haven’t appreciated the scale at which these prehistoric people engineered their landscape and have thus underestimated just how complex their society was.

“What Maria has found at Two Medicine River is unparalleled to my knowledge,” says Brink. “It’s great evidence for complexity that doesn’t exist elsewhere. But then again, no one has looked in one area with the same intensity as Maria. It’s as if she’s looking through a small window and has found this massive kill zone, but there could be others on this scale elsewhere in the northern Great Plains. We just don’t know.”

When I first saw the place, there were at the foot of the cliffs tons and tons of buffalo horn tips, the most time-resisting of any portion of a buffalo’s anatomy. —James Willard Schultz, 1916

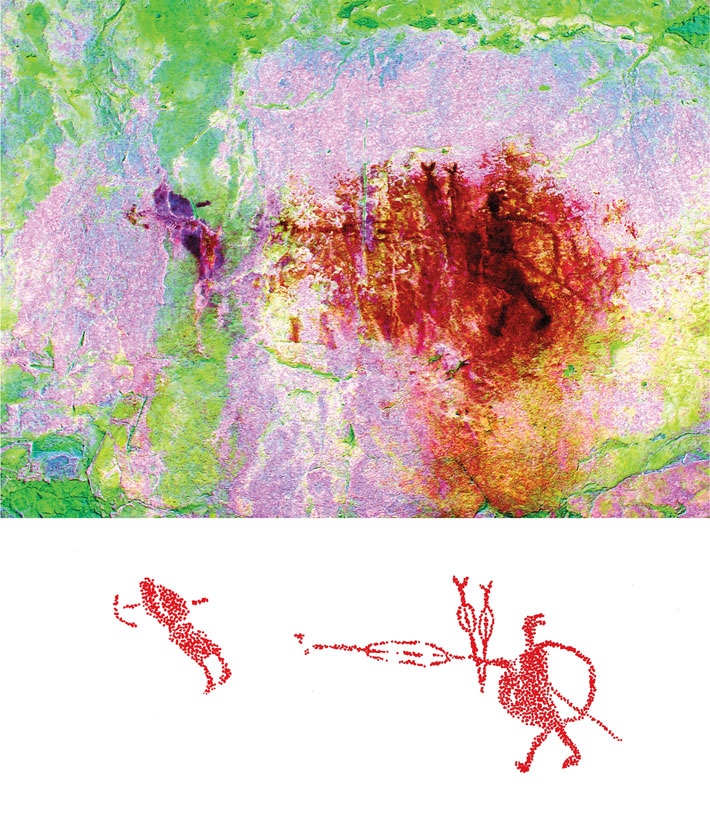

Thanks to historical accounts like that of explorer and author James Willard Schultz and Native American oral tradition, we have a vivid picture of how buffalo jumps were conducted and the rituals that were performed to ensure their success. In Blackfoot culture, inniskim, or marine fossils, were thought to be important in luring buffalo, and they played a large role in rites held before the hunt commenced. Archaeologists still find inniskim around buffalo jumps today, a hint of how hunting and ritual were intertwined.

Though each jump was different, broadly speaking, they all involved a series of drive lines, consisting of cairns that held wooden scarecrows or large collections of brush, and marked a path from a place where buffalo might congregate, across the undulating prairie, to the jump itself. Once an unsuspecting herd was selected, one hunter would don the skin of an infant buffalo, and imitating its distress call, attempt to lure a herd into the drive-line system. Other hunters, perhaps wearing wolf pelts, would urge the herd on from the rear. As the buffalo neared the cliff, other members of the tribe would stand near the cairns and, waving skins, attempt to panic the herd until its growing speed made turning back from the drop impossible. The hunter wearing the infant buffalo skin would jump out of the path of the onrushing buffalo at the last possible moment—but there are many accounts of these hunters falling to their deaths.

Eight miles downriver of the Magee site, at the Schultz site (named after the explorer, who was adopted by the Blackfeet tribe and is buried nearby), the extent of the enterprise is visible today. There are no horns protruding from the ground as they did in Schultz’s time, but as Zedeño picks her way up the steep slope, it becomes apparent that it is impossible to make a step here without walking on bone fragments, the residue of hundreds of separate hunts. The team has excavated greasing and roasting pits here as well, which the ancestral Blackfoot would have used to process the meat into pemmican, a dried meat mixed with grease and berries that, along with buffalo hides, would have been an important trade good.

At the top of the cliff, the scattered stone remains of drive lines are visible, with some stretching into the middle distance, where a herd of horses is grazing. Curious about Zedeño, 10 horses split away from the others and gallop toward the archaeologist. Their swift charge illustrates a key feature of buffalo jumps: As they near Zedeño, the horses dip in and out of sight. Buffalo jumps are often sited near especially uneven landscapes, which would have hidden the cliff edge from the view of the buffalo until it was too late to turn aside.

The heads of the curious horses pop up about 20 feet from Zedeño. After slowing to appraise her for a moment, their curiosity is satisfied, and they head back to the main herd, galloping over 500-year-old stone alignments now concealed by grass.

In historic times among the Blackfoot, three powerful societies managed the hunt—the Buffalo Women society, the Beaver Bundle society, and the Buffalo Chaser society. These groups, which included men and women from different bands, controlled the ritual knowledge and rules of the buffalo hunt and distributed sacred medicine bundles that were accompanied by certain rites that enshrined these rules. Zedeño and her colleague John Murray, the Blackfeet tribal historic preservation officer, think these societies developed out of an ancient, highly ritualized, buffalo-based political system that evolved when the ancestral Blackfoot began practicing communal hunting after the climate shift around A.D. 900 that led to a surge in the buffalo population.

A practitioner of Blackfoot rites himself, Murray lives in a part of the river valley known as “Motaatusi,” or “Place Where the Bundle Owners Live.” He has kept several sacred bundles before giving them away to other Blackfeet tribal members, and this summer he received the Thunder Pipe Medicine Bundle, which traditionally is opened once a year, after the first thunder in the spring. It’s been more than a hundred years since the last buffalo jump, but medicine bundles still circulate on the reservation, and the ceremonies and rites that accompany them help traditional Blackfoot culture thrive.

A day after holding a sweat lodge ceremony marking his acceptance of the Thunder Pipe, Murray accompanies Zedeño to a buffalo jump complex about 10 miles downstream of the Schulz site, named for Kutoyis, the Blackfoot creator hero. The drive lines here are among the most elaborate ever recorded on the High Plains. Zedeño and Murray ride in a pickup truck across the vast site, which links watering holes along Big Badger Creek, a tributary of Two Medicine River, to a series of low cliffs. Unlike at other sites, where picking out the subtle arrangement of rocks can sometimes be difficult, the cairns at Kutoyis are almost immediately in evidence. While looking at the sinuous lines of stones snaking across gentle swales, Murray points out that they are suggestive of the movement of a wolf hunting its prey. “Wolves work together to surround their prey,” he says. “We have a tradition that it was the wolf that taught men to hunt buffalo.”

A map of Kutoyis, created after many months of surveying, shows a dense network of drive lines, many of which seem to have been repaired and used multiple times. Zedeño and her team have recorded 2,581 cairns here, making it by far the most elaborate of the drive lines they have studied. The first time ancestral Blackfoot used the site seems to have been around A.D. 1210, and there are records suggesting a hunt was held here in 1886, probably one of the last buffalo jumps to have been run. By that point, the buffalo were on the edge of extinction. Today, the Blackfeet tribe maintains a small herd of buffalo, which winters at the Kutoyis site and grazes among the remains of the drive lines. Three years ago in an experiment, Zedeño and her team modeled the impact of a buffalo herd being driven off the cliff by rolling dozens of tires down a cliff near Kutoyis. “We were able to predict where the tires would hit quite successfully,” she says. “But it wasn’t anything close to what it meant to see a herd of buffalo running at 30 to 40 miles per hour and then falling at once. It’s beyond an average person’s imagination.”

Buffalo jumps were surely not as dramatic as those in romantic paintings, and the subtle lines of rocks that mark the landscape along the Two Medicine River valley are hardly impressive when viewed individually. But once understood, the scale of what happened here is unmistakable.