One morning in 2008, while waiting for a light to change at the corner of Wilshire and Sepulveda Boulevards in Los Angeles, archaeologist Anthony Graesch jumped out of his pickup truck. In the 75 seconds between green lights, much to the mystification of his fellow commuters, he swept all the garbage—primarily hundreds of cigarette butts—that had accumulated against the curb of the median into a 10-gallon trash bag. Graesch tossed it into the truck bed, hopped back in the cab, and continued to his office at the University of California, Los Angeles, where he was a postdoctoral researcher in anthropology and archaeology.

Like many archaeologists, Graesch says, he looks down a lot, reflexively observing the bits of urban flotsam around him, and he had developed a minor obsession with cigarette butts. “I couldn’t stop seeing them,” he says. A few years later, when he took a full-time position at Connecticut College in New London, where he is now chair of the anthropology department, this interest and that bag of L.A. curbside trash went cross-country with him.

Garbage has long been a critical part of the human material record to archaeologists, middens, privies, and trash heaps are consistent sources of knowledge, full of bones, potsherds, broken tools, pipestems, and more, across the world and throughout human history. “It’s pretty much the bread and butter of archaeological research,” says Graesch—so much so that when archaeologists began to look at the contemporary world, garbage was a natural target. In the 1970s, William Rathje, a legendary archaeologist at the University of Arizona, pioneered the field of garbology, or the study of modern waste using archaeological methods. There have been many other examinations of modern artifacts, but decades later Rathje’s work remains the most cited example of archaeology of the contemporary—how modern material culture reflects behavior and society.

Graesch’s impulse to collect trash, which grew from the work of Rathje and others, has again brought the archaeological eye to modern rubbish and is providing a useful approach for teaching theory and methods to his undergraduate students. Among the challenges of teaching archaeology, Graesch explains, is demonstrating why archaeology matters. Modern artifacts, he has found, can help illustrate how behavior relates to community and how modern questions and problems appear, and can be studied, in the material record.

It’s little surprise that Graesch saw cigarette butts everywhere upon his arrival in Connecticut. He observed that they were clustered around the town’s high concentration of bars, each with its own style: sports bars, biker bars, rock ’n’ roll bars, gay bars, an Irish pub, and others. This got him thinking about drinking establishments and how a small city such as New London could support so many. They are places where people congregate primarily for social purposes—a role historically served by town squares, markets, or churches. “Identity,” Graesch says, “is at the root of all archaeological research, even if it isn’t explicitly recognized as such. We aim to understand the behaviors—social, economic, political, religious—that bring together and divide groups of humans.” In these social spaces people form shared identities, identities that might be visible in their material culture.

Smoking often goes hand in hand with drinking, but Connecticut, like many states, doesn’t allow smoking in bars. So the habit has become part of an extended social experience as patrons leave their seats and assemble outside. “I began to think more critically about the analytic possibilities of cigarettes,” Graesch says. The cigarettes themselves, including how they were smoked, put out, and disposed of, could be markers of social belonging in the community formed by each watering hole.

Graesch teaches a class on the archaeology of modern life, Urban Ethnoarchaeology, and he mentioned his thoughts on bars and cigarettes to students in search of a project. What began as a pilot study of four bars soon grew to consume the course and the archaeology lab. The cigarette project offered intensive training in field collection, documentation, analysis, and interpretation. But it wouldn’t be easy. “He did not waste any time making sure any romanticized notions of what archaeological practice is were obliterated,” says Sarah Shankel, a student in that first class in 2012 who has just completed a graduate degree in anthropology.

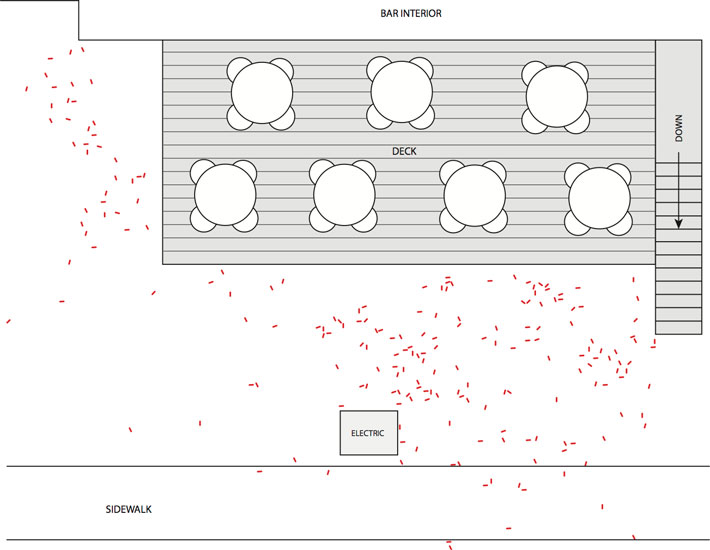

Graesch and his students—soon all were taking part—started collecting cigarette butts, as well as observing the bars and talking to owners and employees to learn more about the community frequenting each one. Across 30 days of collection at 26 sites (23 of them bars, 19 within a quarter-mile radius), they collected, by gloved hand, more than 42,000 specimens from gutters, sidewalks, decks, under decks, deck “toss zones,” and other spaces. “There’s nothing quite like waking up early on the weekend to go crawl around in front of a bar picking up people’s poorly disposed-of cigarette butts,” says Shankel. “The comedic aspect of it didn’t escape us.”

They did ethnographic work to see where people smoke, to fine-tune collection schedules (to account for, for example, a 1980s glam rock karaoke night and a hip-hop DJ night at the same bar), and to document the behavior of street cleaners, janitors, and the occasional sweeping bar owner. They collected from the same sites multiple times (unlike other archaeological sites, these “repopulate” with artifacts in a short period of time), for a total of more than 700 surface collections. The bag from Los Angeles also made a reappearance, as a non-bar control sample. “We were aiming for a robust data set,” Graesch says.

The next challenge was to document, identify, and classify the butts. Graesch and his students needed a comparative collection, the same way an archaeologist excavating a household midden might need a collection of mammal bones against which to compare and classify their finds. Their research turned up some 67 brands produced by 24 manufacturers that comprised some 341 unique types of cigarettes with distinctive sizes, tipping paper, icons, bands, lettering, and more. Using funds from a supportive dean, they bought more than 350 packs, which Graesch calls “the largest collection of cigarettes as well as the most comprehensive cigarette and cigarette package catalogues at an institution of higher education.”

The artifacts, in a word, stank. Combined with the knowledge that each of the butts had spent recent time in someone’s mouth, Graesch says, “you’ve got one of the least charming artifacts, ranking somewhere lower than a discarded nip [liquor] bottle, but well above a soiled disposable diaper.” They ran air purifiers in the lab, became experts in ventilation, and packed sample boxes with newspaper treated with vinegar and baking soda. “I never smelled cigarettes on my clothes and, as far as I’m aware, neither did any of my friends,” says Tim Hartshorn, another student in that first class who went on to serve as a lab assistant and is now coauthoring a journal paper with Graesch. “Then again, who knows? Maybe they all thought I’d taken up smoking.”

The contents of each sample bag were placed in a plastic tray and then the butts were allotted to petri dishes based on type and provenience. “We sorted through our collection bags like we were digging for gold,” says Zoë Leib, a student in the 2013 class. “Really stinky, damp gold.” The students documented the presence of lipstick or gloss, weathering, how much unsmoked paper remained, and the method of extinguishing (the twist, the crush, the twist and crush, and the “I’m so angry I’m going to squish it into a tiny ball”—terms of art, all). Each of these attributes may reflect, together or in isolation, some aspect of the social ritual of smoking and bar-centric community building.

“The students were champs,” says Graesch. “My students see cigarettes in ways that the average passerby does not.” This sort of “professional vision,” like being able to see and document strata at an excavation or spot a potsherd in the dirt, only comes with hands-on experience and repetition. “Within a couple of weeks, students were thinking more critically about the relationship of objects to behavior and beginning to formulate new hypotheses about the content and organization of assemblages in certain spaces,” he adds. The students also began to understand the behaviors and natural processes, known as site formation, that alter the distribution, frequency, and variety of artifacts. Rain causes butts to accumulate against curbs, but also washes some away. Crabbers—“cigarette foragers”—nick artifacts the way an amateur collector or looter might. And the students have become, like Graesch, hyperaware of cigarette butts on the street. “After you’ve contemplated their analytical value,” Graesch says, “it’s difficult to ‘unsee’ these artifacts.”

The result was a massive data set. Its size and complexity permitted Graesch and his students to connect the humble artifacts with social cohesion, environmental impact, and the chemical signals that future archaeologists might associate with our time. “I like to think that this project turns ‘normal’ on its head,” Graesch says, “and makes visible a material record that is otherwise, and surprisingly, invisible and unnoticed.”

In the ongoing, preliminary analysis, Graesch and a new batch of students are finding that the types of cigarettes smoked and discarded does indeed “map” onto the types of bars in the study—but only with careful controls that account for when a bar’s regular patrons are present. On a busy Friday night, or a night with some other event that attracts additional patrons, the assemblage of butts in front of a given bar might be far different from when that bar’s core community—the regulars, think Cheers—are there. “Looking at the individual butts as data points, each fitting into their own taxonomical species, each carrying an evolutionary story, meaning, indication of the environment,” says Leib, “I can no longer look at a cigarette butt without wonder.”

In the course of the project, Graesch was struck by the variety of different types of cigarettes, including the exotics that found their way from all over the world to the small city. “These little artifacts evince a frequency and type of transience that isn’t otherwise signaled in the built environment and material record,” he says.

Graesch and his students were also intrigued and troubled by the staggering volume they collected in just a few dozen days, and the potential ecological impact. Why, he and his students thought, should this kind of litter in particular be so widely tolerated, even though cigarette butts hold many toxic compounds that can leach out into rivers, lakes, and oceans? “I can think of no other social science better equipped than archaeology to ferret out the complex behaviors accounting for the unregulated and unquestioned discard of hazardous waste on the urban landscape,” he says. “I imagine archaeologists working more closely with environmental scientists, municipalities, and the architects of public policy.”

According to Graesch, the “archaeology of toxicity” they’ve begun to examine is particularly interesting to students—and could also be to archaeologists of the distant future. “The toxic residue of everyday life in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries will likely be the subject of environmental archaeology for decades to come.”