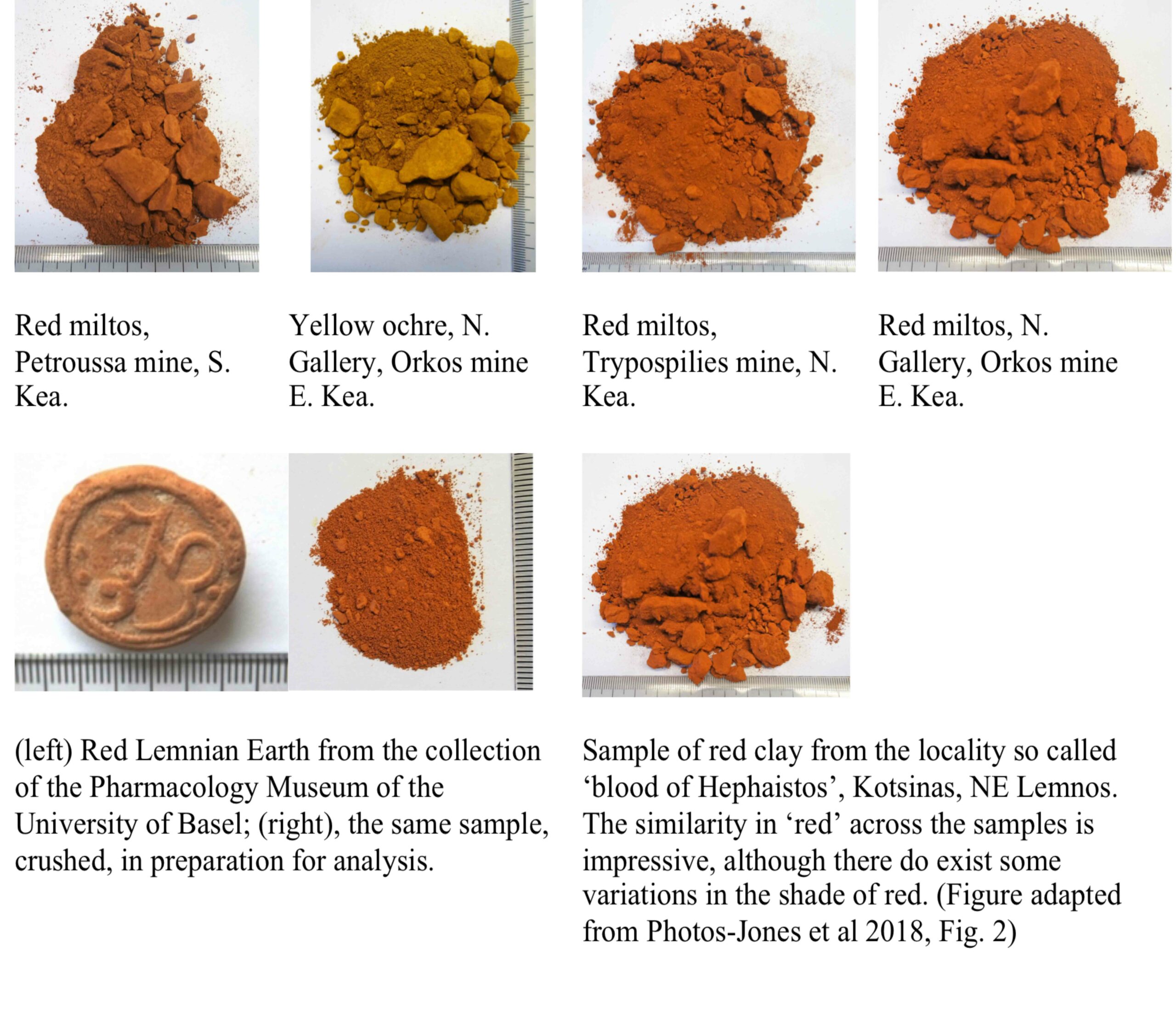

To the Greeks and Romans, a red pigment known as miltos was a sort of multipurpose supersubstance. Ancient writers, from Theophrastus to Pliny, record that the finegrained, red iron oxide–based material was much sought after for use in decoration, cosmetics, agriculture, medicine, and even boat maintenance. A new study indicates that one of the reasons miltos was so versatile is that not all miltos was created equal.

An international team analyzed the mineralogy, geochemistry, and even microbiology of miltos samples recovered from the Greek islands of Kea and Lemnos, and has been able to identify subtle variations that made each sample suitable for a particular use. “Different sources produced different types of miltos,” says University of Glasgow archaeologist Effie Photos-Jones. “It was not a pure mineral but rather a combination of minerals. There are also variations in the microorganisms that live in the immediate vicinity of those minerals.” For example, some Kea miltos samples contain microorganisms that would have enhanced their use as a fertilizer. Others contain high concentrations of lead, which could help prevent growth of harmful biofilms and barnacles on ships’ hulls. One sample from Lemnos has traces of titanium dioxide, a known antibacterial compound, making it useful for medicinal purposes.