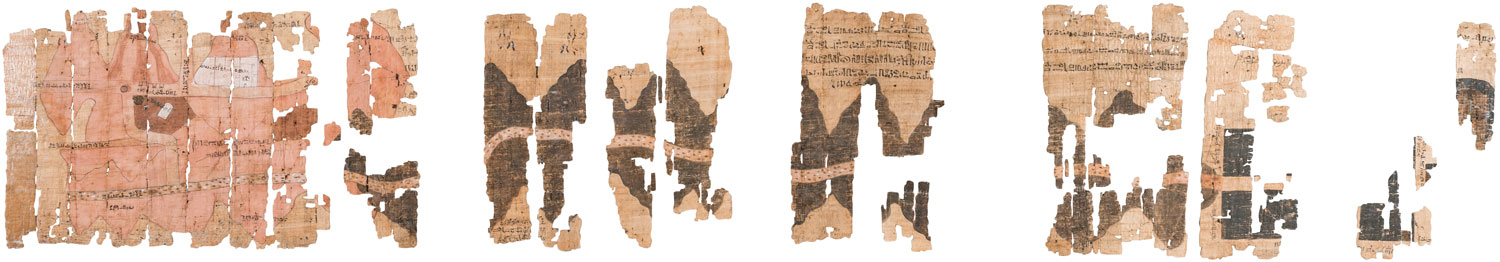

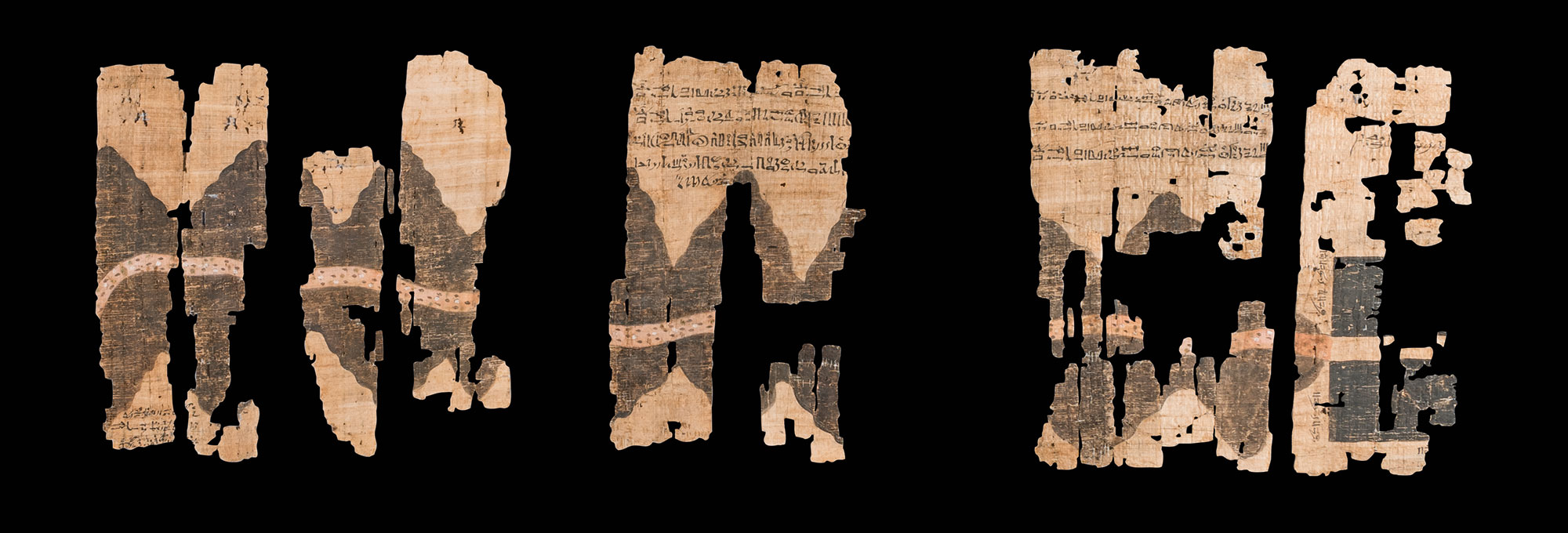

The world’s oldest known geological map is a nine-foot-long papyrus from the Egyptian village of Deir el-Medina, home to the New Kingdom craftsmen who worked in the Valley of the Kings. Created by Amennakhte, the chief scribe of the royal necropolis, the papyrus depicts a dry riverbed called the Wadi Hammamat in Egypt’s eastern desert. The wadi had been used for quarrying and mining for centuries, and as a route connecting the Nile Valley to the Red Sea for millennia. No map would have been needed for general travel, according to Egyptologist Andreas Dorn of Uppsala University and linguist Stéphane Polis of the University of Liège. Instead, the papyrus was created as a commemorative record of a pharaonic expedition, perhaps during the reign of Ramesses IV (r. ca. 1153–1147 B.C.), to a bekhen-stone quarry. Bekhen-stone, or greywacke, was prized for use in high-quality sculptures. To distinguish types of stone, Amennakhte employed dark brown to represent bekhen-stone, pink for deposits of granite and gold, and spots for alluvial deposits.

The scribe also included quarried bekhen-stone blocks with their measurements, as well as roads and directions in hieroglyphs, such as “road leading to the sea.” Amennakhte also drew natural and built landmarks including small trees, bushes, and a well, along with a monument to Seti I (r. ca. 1294–1279 B.C.) and a temple to the god Amun, both illustrated in white at the far left. “Amennakhte definitely had experience visualizing complex structures, as he was also responsible for drawing tombs. He was able to represent topographical information by flattening out such things as roads and the natural environment,” says Polis. “This unique document mixes geographical and geological information in a way that anticipates many of our modern mapmaking practices.”